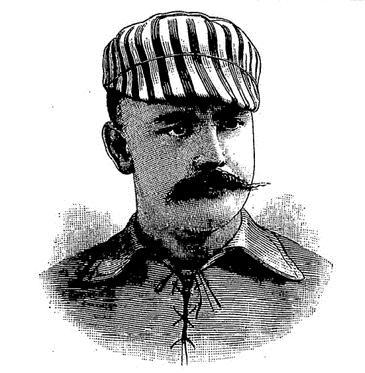

Jumbo McGinnis

There is a picture of the 1882 St. Louis Browns, one of the inaugural teams in the American Association and the forerunner of today’s St. Louis Cardinals. On the absolute left of the group, a mature Jumbo McGinnis stands, arms crossed, one leg thrust forward, chest back, staring confidently at the camera. He is a solidly built gent, carrying his 197 pounds well. McGinnis was Chris Von der Ahe’s ace pitcher during the team’s first three years in the new “common man’s” league. But the workload from his 130 starts (123 complete games) was too much for his pitching arm and after a few more years of limited action, his baseball career was over.

There is a picture of the 1882 St. Louis Browns, one of the inaugural teams in the American Association and the forerunner of today’s St. Louis Cardinals. On the absolute left of the group, a mature Jumbo McGinnis stands, arms crossed, one leg thrust forward, chest back, staring confidently at the camera. He is a solidly built gent, carrying his 197 pounds well. McGinnis was Chris Von der Ahe’s ace pitcher during the team’s first three years in the new “common man’s” league. But the workload from his 130 starts (123 complete games) was too much for his pitching arm and after a few more years of limited action, his baseball career was over.

The records and information for George Washington McGinnis’s birthdate and place are inconsistent. His death certificate notes his birthdate as February 22, 1864, but his gravestone shows 1858. Census records from various years infer dates between 1856 and 1858, while a New York Clipper article infers 1858. Similarly, McGinnis’s place of birth is debated. In the 1880 census, he reports his place of birth as Missouri. But in 1900, 1910, and 1920, he reports it as Illinois. Also, his children universally report their father’s birthplace as Illinois on census records when they were adults. A Clipper article from 1883 reports him as being born in Alton, Illinois. He also reports his birth city as Alton in the birth record of his daughter Addie. Since Alton, Missouri, wasn’t platted until 1859 and is located 180 miles from St. Louis, Alton, Illinois, is the most likely spot.

Information on McGinnis’s father, Richard McGinnis, and mother, Minta (Moss) McGinnis, is similarly very bare and there is no information on other siblings. At some point when McGinnis was a boy, his family moved to St. Louis. As he grew up, he took up a trade, glassblowing, along with playing baseball. As early as the 1880 census, he listed his occupation as glassblower. Also on that census, he was already married to Catherine (Sherlock). That marriage was inferred to have taken place sometime in 1878. He also was reported to have played for the local teams Our Boys and Lyons Club in 1877 in his first documented playing appearances.1

In 1879 McGinnis was the pitcher for the semipro St. Louis Brown Stockings. This team played mainly on Saturdays, allowing him to pitch every game. They did make a road trip to Cincinnati and Louisville, winning three of four games. But due to the schedule, McGinnis couldn’t pitch the third game of the trip against Louisville which led to the only loss suffered by the Brown Stockings that season.2 In 1880 he continued with the Brown Stockings, leading them to a 24-1 record against mainly local competition, further stoking St. Louis’s interest in baseball. That 1880 season included a game with a “lively” ball, on August 22 with McGinnis and the Browns overturning the local Reds, 18-9. “[Their fans’] expectations were realized, in that the sphere was sent flying to all parts of the ground, and the outfielders were afforded their share of the work, as in old time games.”3

In 1881 Al Spink, founder of The Sporting News, and Ned Cuthbert persuaded Chris Von der Ahe to become more involved in baseball. Von der Ahe purchased the lease on the St. Louis ballpark (Sportsman’s Park I) and financed significant upgrades. Spink brought better competition into town to face the Brown Stockings. The team responded with a 35-15 record and attendance increased. McGinnis threw a five-inning no-hitter against the Louisville Eclipse on October 24 of that season.

It was time for a new major league. St. Louis, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Louisville, Philadelphia, and Baltimore were the initial entries in the first year of the American Association, 1882. Since several of the owners of these teams were in the beer and/or whiskey business, they decided that the league would allow alcohol sales, play games on Sundays, and charge 25 cents for admission. These rules were in effect to appeal to a more blue-collar audience and therefore to compete with the National League. Von der Ahe’s St. Louis Browns were largely composed of his players from the 1881 team, including Jumbo McGinnis.

On May 2, 1882, McGinnis matched up against future teammate Tony Mullane and the Louisville Eclipse in the first game played by the modern St. Louis Cardinals franchise. He wasn’t stellar but was victorious in the 9-7 game. A few days later, on May 10, he had the honor of pitching the first home game that the Pittsburgh Allegheny (modern Pirates) played. Always the accommodating player, he was on the losing side of a 9-5 score.

McGinnis was St. Louis’s ace pitcher for the first three years of the American Association. He compiled a .606 winning percentage for a team that played .593 ball. He was not an overpowering pitcher, being referred to as a strategist. “Some of the most effective work done in the pitcher’s ‘box’ in 1884 in the professional arena, was accomplished by a minority of the American club pitchers, some of whom vied with the best pitchers in the League arena in strategic skill. Noteworthy among these strategists were … McGinnis of the St. Louis.”4

Owing to his physique, McGinnis was not a good fielder or baserunner. His nickname, Jumbo, derived from his size, but he wasn’t out of shape. His build was attributed to blowing glass, and not to overeating.5 In the offseason he would weigh over 200 pounds but would get down to his listed weight by the start of the championship season.

McGinnis was admired by the fans. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote, “‘Many readers’ ask that the ‘Jumbo’ battery, McGinnis and (Dan) Sullivan, be played in a Sunday game as many of their admirers find it impossible to attend week-day games.”6 He was also very popular among his teammates and peers. “George is, perhaps, the most popular man in the business, and if a vote were taken amongst the professionals themselves on that score, he would receive a very large majority,” said the Post-Dispatch.7

McGinnis led the league twice during his career. In 1882, he hurled 40 wild pitches, outpacing Tony Mullane by 7 (in 78 fewer innings) and in 1883 he completed six shutouts, tying Will White for the league lead. But he was a fine pitcher these years. Using his pace and curves, he finished third in the league in ERA in 1883, fourth in wins in 1882, and fifth in wins in 1883. He also pitched some stellar games, including a three-hit 1-0 victory against Baltimore on August 21, 1883.8 An improved St. Louis finished second by one game to the Philadelphia Athletic while McGinnis was 2-4 in his six starts against the eventual pennant winner.

For the St. Louis Browns to embark on their four-year pennant run, they needed just a little bit better pitching. The Browns added two promising pitchers for the 1884 season, Dave Foutz and Bob Caruthers. Foutz started 25 games in 1884 and the young Caruthers started seven. These two were also strong batsmen and good position players. The Browns finished 67-40, good for fourth place in the very competitive league.

For the 1885 season, Foutz and Caruthers became the number-one and -two pitchers of the Browns, starting 99 games, leaving McGinnis with just 13 starts for the season. He went 6-6 with a league-average ERA in his limited duty. He was inconsistent, hurling three shutouts and a 2-1 one-hit victory (the lone hit coming when he was slow to cover first base on a groundball),9 but also giving up double-digit run totals three times. But the media reported that he was still capable. “If any doubt still exists about George McGinnis’ effectiveness in the box, it certainly arises from a prejudice against the jumbo twirler,” wrote the Post-Dispatch.10

In 1886 McGinnis was nothing more than a third wheel on the Browns. Foutz and Caruthers again teamed to start 100 games, pitching at a high level, and played in the field. Nat Hudson was added as a change pitcher and McGinnis started only 10 games. St. Louis showcased him against Baltimore on July 8, with McGinnis throwing a 10-0 victory. Baltimore bought his contract that evening.11 He pitched regularly for Baltimore the rest of the year, compiling an 11-13 record (to go with his 5-5 record for the Browns) with a league-average ERA.

Baltimore had seen enough but Cincinnati was interested and signed McGinnis for the 1887 season. “Manager (Gus) Schmelz telegraphed to President Stern this morning to sign George McGinnis. George is good for at least one excellent game a week and he is Weidman’s superior in batting. ‘Mac’ will doubtless be with us by Monday,” wrote Sporting Life’s Cincinnati correspondent.12 He started well, winning three of his first four starts, but lost the last four, giving up double-digit runs in three of them. His last major-league start was a 17-5 shellacking by the unimpressive Brooklyn Greys. His arm was finished and Cincinnati released him. He pitched two ineffective games for the Northwestern League Milwaukee Cream Cities later that summer and two fill-in games with the Central Interstate League Evansville Hoosiers in 1890.

McGinnis filled in as an umpire a few times after his baseball career was over. “The regular umpire failed to appear and George McGinnis, the old St. Louis pitcher, filled that position to the satisfaction of all,” a newspaper noted.13 His primary occupation continued to be working as a glassblower. He and Catherine had six children (George, Adeline, Harry, Joseph, Evelyn, and Julia), five of whom survived into adulthood. Glassblowing was a physical job that took a toll on McGinnis’s eyesight, eventually causing it to fail, and he had to quit his job. But a St. Louis newspaper found out about his plight and helped raise money for corrective eye surgery.14 The cataract surgery was successful and his eyesight was restored. However, he didn’t go back to glassblowing and instead by 1910 he reported being a city inspector. He did stay in touch with baseball, appearing at the National League Golden Jubilee celebration in St. Louis on June 18, 1925.15

Catherine McGinnis died on January 31, 1929. After his wife’s death, he moved in with his daughter Adeline and lived with her until his death from stomach cancer on May 18, 1934. The funeral services were held at Holy Name Catholic Church and he was interred at Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and verified for accuracy by the BioProject fact-checking team.

Sources

Ancestry.com.

newspapers.com.

Notes

1 “Our Browns,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 3, 1884: 9.

2 Jon David Cash, Before They Were Cardinals (Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2002), 57.

3 “Browns vs. Reds,” New York Clipper, September 4, 1880: 187.

4 Spalding Base Ball Guide, 1885, 56.

5 Robert Tiemann, ed., Nineteenth-Century Stars (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2012), 178.

6 “Amateur Base Ball Notes,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 9, 1885: 7.

7 “Our Browns,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 3, 1884: 9.

8 “Games Played Tuesday, August 21,” Sporting Life, Volume 1, Number 20: August 27, 1883: 5.

9 Tiemann, Nineteenth-Century Stars, 178.

10 “The Browns Show the Eclipse How to Play Ball,” St. Louis Post Dispatch, August 7, 1885: 5.

11 Tiemann, Nineteenth-Century Stars, 179.

12 “From Cincinnati,” Sporting Life, Volume 9, Number 1, April 13, 1887: 7.

13 ““St. Louis 2, Athletics 0,” Times-Picayune (New Orleans), August 13, 1888: 2.

14 Tiemann, Nineteenth-Century Stars, 179.

15 “Baseball Notables Here for Jubilee Game Tomorrow,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 17, 1925: 22.

Full Name

George Washington McGinnis

Born

February 22, 1864 at Alton, IL (USA)

Died

May 18, 1934 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.