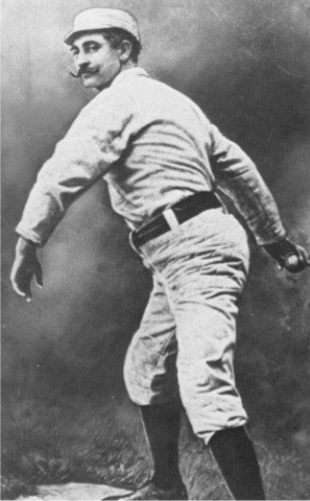

Tony Mullane

Among the baseball accomplishments in Tony Mullane’s career, two events in 1882 stand out in particular: becoming the first ambidextrous pitcher in major-league history on July 18, while with the Louisville Eclipse of the American Association, and tossing a no-hit game on September 11.

Among the baseball accomplishments in Tony Mullane’s career, two events in 1882 stand out in particular: becoming the first ambidextrous pitcher in major-league history on July 18, while with the Louisville Eclipse of the American Association, and tossing a no-hit game on September 11.

Anthony John Mullane, also known by the nicknames the Count and the Apollo of the Box, was born on January 30, 1859, in County Cork, Ireland. He pitched for four teams in the National League (Detroit, Cincinnati, Baltimore, and Cleveland) and four in the American Association (Louisville, St. Louis, Toledo, and Cincinnati) between 1881 and 1894. Well known as a ladies’ man, Mullane also was a proficient boxer, as well as a competitive roller skater and ice skater.

Mullane was the oldest son of Dennis Mullane, a laborer born in 1827, and Elizabeth (Behan) Mullane (born 1828), a homemaker. Anthony had two brothers, John (born in 1874 in Pennsylvania), and Sam (born in 1865 in New Jersey), and a sister, Nora (born in 1860 in Ireland). In 1862, when Anthony was 3, the family emigrated to the United States.

In his book A Fine-Looking Lot of Ball-Tossers, Richard McBane wrote that, while living with his family in Erie, Pennsylvania, Mullane “would run away from home and play ball. He wouldn’t learn a trade. He imagined he was cut out for a ball player and he undoubtedly was. He filled the box in several amateur games in Erie, and then became discontented because no pay was attached.”1

Mullane is said to have begun his professional baseball career in Ohio, where he played for a number of local teams, including Cambridge and Akron during the 1880 season. But McBane wrote that Mullane signed a professional contract in 1876 with the Geneva, Ohio, team for $1 a day plus room and board; between 1876 and 1880, he apparently drifted from club to club in eastern Ohio and western Pennsylvania before joining the Akron team.2 Early in the 1881 season, Mullane played for Akron again, against other amateur teams in Ohio as well as National League teams that would play Akron when they were playing near Cleveland, which had a National League franchise. There also is a record of Mullane playing with the local White Sewing Machine team in 1881 as a center fielder.3

As of May 1881 Mullane was playing again with Akron, a member of the League Alliance, which placed the Akron team under the rules of the National League and allowed the team to play League teams. Among the League teams that they played during the 1881 season were Cleveland, Boston, and Worcester, with Mullane playing well as a pitcher, first baseman, and outfielder. In July of 1881 it was rumored that Mullane would leave the Akron team to play for the Louisville Eclipse of the American Association.4 Instead Mullane went to the Detroit Wolverines of the National League in August and played in five games as a change pitcher, with a 1-4 record and a .263 batting average.5

In 1882 Mullane went to the Eclipse. He played in 77 games, 55 of them as a pitcher, and also played first base, second base, and the outfield; he batted .257 and compiled a 30-24 record on the mound, with a 1.88 ERA. He pitched in particularly memorable games. On July 18 in Baltimore, After giving up seven runs in three innings to the lowly Orioles, the right-hander began pitching with his left hand, becoming the first ambidextrous pitcher in major-league baseball. And on September 11 Mullane pitched a no-hit game against the Cincinnati Reds, the first no-hitter in the American Association.

Mullane’s talents attracted the interest of other teams and in August 1882, the Cleveland Dealer reported that he had signed with the St. Louis Browns of the American Association for the 1883 season. Mullane continued his winning ways with his new team, posting a 35-15 record with a 2.19 ERA. After the season the Browns reserved his contract for the 1884 season. However, a new league, the Union Association, was forming, with a franchise in St. Louis, and the new team, the Maroons, reportedly signed him as a pitcher, giving him $500 in advance money. The president of the Browns, Chris Von der Ahe, said he would not punish Mullane for breaking the reserve rule as he himself opposed the rule. Meanwhile, before the 1884 season began, the Toledo club of the American Association offered Mullane a contract reported at between $4,000 and $5,000 to jump back from the Union Association and he did so, with Von der Ahe’s blessing.

Mullane became much sought after. The Boston Herald described him as “a most effective pitcher; his delivery is low and his command of the ball wonderful. He pitches with left or right arm equally well.”6

One of Mullane’s catchers in Toledo was Moses Fleetwood Walker, who is credited by some as the first African American to play major-league baseball. While pitching for Toledo in a game in St. Louis on May 4, Mullane felt the wrath of the crowd. He was called a contract breaker and cheat, and was hissed when he hit and raucously cheered when he struck out. To the crowd’s disappointment, Mullane showed little or no reaction.7 The next day the Browns applied to the circuit court in St. Louis for a restraining order preventing Mullane from playing for any team other than the Browns. The issued the restraining order, but it was immediately overturned by a federal judge who said the courts’ time should not be occupied by baseball matters and that it was beneath the dignity of the courts to notice.8 Mullane rejoined Toledo on May 14 and in 95 games hit .276 and won 36 games while losing 26, with an ERA of 2.52 and a career-high 325 strikeouts.

In August 1884, it was reported that several clubs, including Cincinnati of the American Association, anticipating that the Toledo club would fold, were interested in acquiring Mullane’s services. On November 5 Mullane signed with Cincinnati for an estimated $5,000, with a $2,000 advance; however, his signing by the Reds violated an agreement Mullane had made with the St. Louis Browns. Mullane was subsequently suspended for a year and fined $1,000 for jumping his contract with Toledo. An attempt to reinstate Mullane fell flat when a satisfactory agreement between representatives of the teams could not reached. Mullane pitched some games for local games in Ohio in 1885 and was reinstated at the end of the American Association season on October 2. He pitched for Cincinnati against St. Louis in a series of exhibition games, but not in St. Louis because of an injunction granted to the Browns. Mullane, who had trained hard despite not pitching in the major leagues, was in great shape and pitched well against St. Louis.

Signing Mullane for the 1886 season proved difficult for Cincinnati and he threatened to quit baseball for business if his salary demands were not met. But on March 4 he signed with the Reds and later opened a pool room in Cincinnati, which the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune called a “first-class, orderly place.”9 Despite showing up for the season in great physical shape, Mullane was hit hard at the beginning of the season and expressed disgust at his performance, threatening to retire from pitching for good.10 By mid-May, though, he began to pitch like the Mullane of old.

Controversy erupted when the Cincinnati Times-Star reported an accusation that Mullane and four other Cincinnati players had thrown a game on June 4 at Brooklyn.11 The accuser, Patrick J. McMahon, alleged that Mullane told him to bet as much money as he could on Brooklyn to win after the fourth, fifth, and sixth innings, despite the fact that Cincinnati was ahead 7-0 at the end of the seventh inning. With Mullane pitching, Brooklyn scored eight runs in the eighth and four in the ninth to win the game, with 10 of the 12 runs being earned. The Brooklyn club was connected to some New York gambling houses with which Mullane was alleged to have made a bargain. Mullane sued the Cincinnati Times-Star in Ohio superior court, asking for $20,000 for alleged slanderous and malicious libel.12 Meanwhile, an American Association panel cleared Mullane of any charges.13 Mullane finished the season with 33 wins and 27 losses with a 3.70 ERA.

After being reserved again by Cincinnati, and signed for the 1887 season, Mullane was suspended without pay in May and fined $100 for insubordination after refusing to play until his salary was increased. The Red Stockings placed Mullane on their reserve list. If he had merely been released, he could have been claimed by another club. The situation became more complicated when Mullane threatened the president of the Cincinnati club, Aaron Stern, with violence because of the $100 fine.14 Mullane then went to Rutland, Vermont, in early June to play for a local unaffiliated club there for $200 a month.15 But by mid-June, cooler heads had prevailed and Mullane was reinstated by the Red Stockings. Despite the disrupted season, he won 31 games and lost 17.

The 1888 season was relatively uneventful for Mullane, although on August 2 he was arrested at the Brooklyn ballpark on a charge of contempt for failure to appear regarding a charge of not paying for some whiskey, but he eventually paid his bill and the case was closed.16 Statistically, he posted a 26-16 record, increased his strikeout total to 186 from 97 the previous year and reduced his ERA to 2.84 from 3.24; he also umpired in three games. But by 1889 Mullane appeared to be on the decline as a pitcher. His record dropped to 11-9 in only 33 appearances as a pitcher; he also played 34 games as a third baseman, outfielder, and first baseman and batted .296, a career high.

In 1890 Cincinnati moved to the National League. Mullane played outfield, third base, shortstop, and first base while pitching in 25 games. He came back strong on the mound in the second half of the season, posting a 12-10 record with a 2.24 ERA. That strong finish gave the club the confidence that he might be returning to his dominant form of previous years.

In an article written in The Sporting News of July 12, 1890, Mullane spoke of how he was able to prevent “dead arm.” He said:

“… I have had a bad arm on two occasions. Once in Akron my arm went back on me entirely. I did not set around and give it a rest. Neither did I bathe it in arnica or high wines. I simply put on two heavy sweaters, and although it hurt me even to raise my arm, I went to work and pitched ball after ball … and it hurt me so badly that I had to grit my teeth. … Had I sat around nursing my sore arm I am confident that I would not now be solid as a pitcher.”

However, after an 1891 season when he won 23 games but lost 26 and saw his ERA rise by a full run to 3.23, the pressure was on Mullane to produce better statistics in 1892 or risk not pitching regularly again, especially since he was an active participant in dissension that had riddled the Cincinnati team. Perhaps contributing to that dismal season was the fact that Mullane’s son had died in July and that Mullane had played injured. After the season Mullane was very close to signing with the Chicago Colts of the National League before his wife intervened and said no to the proposed deal.17

Mullane came back to Cincinnati, won 21 games and lost 13 in 1892, and lowered his ERA to 2.59. In May of 1893, Mullane’s wife of seven years, Barbara, filed for divorce, alleging that he beat her when she criticized his play after a game. In turn Mullane filed for alimony from his wife, with whom he had one child, saying that she smoked cigarettes, drank beer, and lost much of his money in “wild schemes.”18 Cincinnati was enjoined from paying him any money pending resolution of the suit. After a 6-6 start to the 1893 season with Cincinnati, Mullane was traded to the Baltimore Orioles for Piggy Ward and $1,500 on June 16. He finished the season at 18-22, with an ERA of over 4.00. In January of 1894 his wife accused him of threatening to kill her after a dispute and she wanted him arrested for contempt of court, for failure to pay her alimony after a judge had thrown out his attempt to refrain from paying it.19 The Chicago Tribune wrote that Mullane had developed a “sulky temper” in Baltimore, and had been sued for $2,000 by a hotel proprietor for hitting him with a baseball bat, a claim Mullane disputed.20 Perhaps the low point of Mullane’s career on the field came when he was tagged for 16 runs in the first inning of a game against Boston on June 18 en route to a 24-7 shellacking by the Beaneaters. On July 24, 1894, Mullane’s wife was granted a divorce on grounds of extreme cruelty against her and their young daughter. The Orioles traded Mullane to the Cleveland Spiders on July 15, and the Spiders released him on August 4, in part because of an ingrown nail on his left index finger that brought about blood poisoning

After the 1894 season Mullane played 11 games with Oakland in the California Winter League, then in March of 1895 he signed with the St. Paul Apostles of the Western League, disappointed that he was not signed by a National League team. He played in 95 games for St. Paul, batting .320, and compiling a 16-10 pitching record in 218 innings. He played for St. Paul until May 27, 1898, when he became captain and manager of the Detroit Tigers of the Western League. He was released by the Tigers on June 12. He signed with Toronto of the Eastern League for 1899 but retired after only playing seven games.

In December 1896, Sporting Life had reported that Mullane filed an application to the National League to become an umpire.21 A few weeks after the Tigers released him in 1898, the Western League hired him as an umpire. Sporting Life initially reported in August that Mullane was “umpiring good ball,”22 but an article three weeks later indicated that writers in Western League cities felt that “his umpiring is extremely poor” and he “does not seem to have his lines cast in easy parts.”23 Numerous controversies involving Mullane’s calls led to his resignation after the season. After his short stint as a player in Toronto ended in 1899, he became an umpire in the Atlantic League,24 where his umpiring skills showed great improvement. In 1901 he sold a saloon he owned in Chicago and announced that he would resume his quest for an umpiring position in the National League, where the salary was higher. He was hired as an umpire by the Western Association in 1901 season, and took an umpiring job in the Pacific Northwest League in 1902. He left that job because of poor performance, and joined the league’s Spokane Smoke Eaters as a player, appearing in 20 games.

Mullane took a job with the Chicago Police Department as a complaint sergeant in January 1903, but continued to umpire, first in the American Association in 1903, then in the Southern Association in 1904. In 1911 Mullane suffered a near-fatal abscess of the brain. After recovering, he continued working for the Police Department. He died on April 26, 1944. He was survived by his daughter, Ina; his brother, John; and a granddaughter, Dorothy.

This biography appears in SABR’s “No-Hitters” (2017), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Richard L. McBane, A Fine-Looking Lot of Ball-Tossers: The Remarkable Akrons of 1881 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2005), 34-35. McBane cited an 1886 article in The Sporting News.

2 McBane, 34-35.

3 “Akron’s Annihilators,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 27, 1881.

4 “Just Like Him,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 29, 1881.

5 Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 30, 1881. A change pitcher is defined by the Dickson Baseball Dictionary as a relief or substitute pitcher.

6 Boston Herald, April 8, 1884.

7 “A One-Sided Game Between St. Louis and Toledo – A Prize Fight of Seventeen Rounds –Sullivan,” Kansas City Times, May 5, 1884.

8 “Mullane’s Victory,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, May 13, 1884.

9 “Baseball – Tony Mullane Signs to Play With the Cincinnatis,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, March 7, 1886.

10 Kansas City Times, May 11, 1886.

11 “Charges of ‘Throwing,’ ” Boston Herald, June 19, 1886.

12 Kansas City (Missouri) Times, June 17, 1886.

13 “Mullane Vindicated,” Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, July 1, 1886.

14 “Struck Out,” Sporting Life, May 25, 1887.

15 Sporting Life, June 8, 1887.

16 “Tony Mullane’s Arrest,” Sporting Life, August 8, 1888.

17 “Cincinnati Chips – Mullane’s Wife Settles His Case,” Sporting Life, November 21, 1891.

18 “More Troubles for Mullane,” Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1893.

19 “Mullane’s Troubles,” Sporting Life, January 20, 1894.

20 “Tony Mullane Sued for Damages,” Chicago Tribune, May 8, 1894.

21 “Mullane’s Ambition,” Sporting Life, December 5, 1896.

22 Sporting Life, August 20, 1898.

23 Sporting Life, August 27, 1898.

24 Sporting Life, July 8, 1899.

Full Name

Anthony John Mullane

Born

January 30, 1859 at Cork, (Ireland)

Died

April 25, 1944 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.