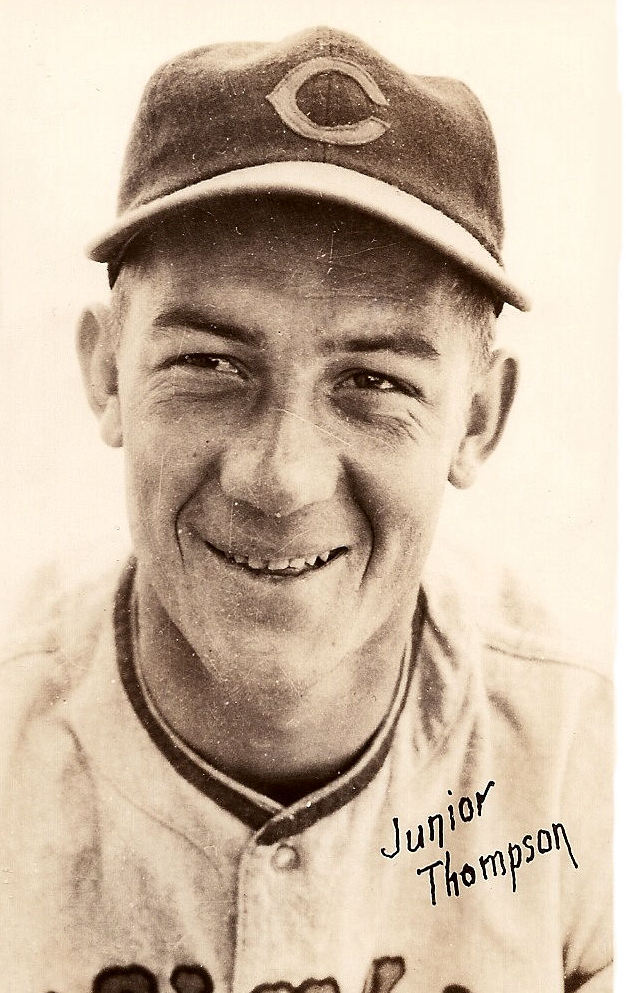

Junior Thompson

Do we call him Junior or Gene? Was Junior his given name or a nickname? Could it be both? No matter. As a fresh-faced youngster Junior Thompson helped the Cincinnati Reds win two consecutive National League pennants. As a mature veteran Gene Thompson impacted the game of baseball for half a century.

Do we call him Junior or Gene? Was Junior his given name or a nickname? Could it be both? No matter. As a fresh-faced youngster Junior Thompson helped the Cincinnati Reds win two consecutive National League pennants. As a mature veteran Gene Thompson impacted the game of baseball for half a century.

Junior Eugene Thompson was born June 7, 1917, in Latham, Illinois, a tiny village in Logan County in the geographic center of the state. He was the second of the six children and the eldest son of Grace Allison Thompson and Earl B. Thompson. Junior grew up in near-by Decatur, where his father for many years was a truck driver for Decatur Township. Baseball reference books agree that Junior’s name was Eugene Earl Thompson, but they are mistaken. His mother wanted to name him Earl after his father, but his grandmother thought that would be too confusing, so they named him Junior Eugene.1 He preferred to be called Gene, but he never changed his name officially, so he is still Junior Thompson in the records of the Navy, Veterans’ Affairs, and Social Security.

After graduating from high school in 1934, the 17-year-old pitcher was signed by Chuck Dressen of the Cincinnati Reds. He started his professional career with the Monessen Reds in the Class D Pennsylvania State Association in 1935. The following season he was still in Class D ball with the Paducah Indians of the Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee (Kitty) League. In 1936 Thompson married Dorothy Jean Thornell of Decatur.

In 1937 he began moving up the ladder quickly. He started with the Peoria Reds in the Class B Illinois-Indiana-Iowa (Three-I) League. Years later he said his greatest thrill as a player came when he retired 27 consecutive batters for Peoria.2 After Peoria it was the Waterloo Reds in the Class A Western League. Then it was to the top of the minor-league chain with the Syracuse Chiefs of the Class AA International League.

In 1937 a Social Security card was issued to Junior Eugene Thompson.

Thompson did not get off to a good start with Syracuse in 1937, so he spent most of the season with the Columbus Reds of the Class B South Atlantic (Sally) League. He had a fine record in Columbus (16-9 .640) with an ERA of 2.81, earning promotion to the majors. That was quite a jump from Class B to the big leagues, but Thompson had previously had experience in the high minors. When he reached the majors he was 21, but he looked even younger. It has been said that he was dubbed Junior by his teammates because of his youth.3 If that story is true, Junior was both his given name and his nickname. The right-handed young pitcher stood 6-foot-1 and weighed 185 pounds.

Thompson made his major-league debut on April 26, 1939, at Busch Stadium in St. Louis. He entered the game in the eighth inning and faced a formidable lineup. First up was the cleanup hitter, future Hall of Famer Joe Medwick. Thompson retired him on a grounder, second to first. Next up was another future Hall of Famer Johnny Mize, who flied out to center field. Mize was followed by four-time All-Star Terry Moore, who hit an easy popup to the third baseman. Thompson had retired the side in order, an auspicious beginning to his big-league career. He continued pitching well throughout the year, as a starter and reliever. His record was 13-5, with an ERA of 2.54. He threw three shutouts and collected two saves.

During his rookie season Thompson was fortunate to have Deacon Bill McKechnie as his manager. McKechine had taken the helm of the Reds in 1938 and immediately led the club to their first first-division finish in more than a decade. He would soon lead them to their first National League pennant and World Series championship since 1919. Not only was McKechnie an astute manager, but he was a fair and decent man, a father-figure to some of the younger players. Thompson said, “I couldn’t have had a better manager than McKechnie. He and his wife were like parents to me.”4 On another occasion he said, “I spent most of my time in the major leagues under one of the greatest managers in the game, Bill McKechnie.”5

Cincinnati faced the powerful New York Yankees in the 1939 World Series.

The Bronx Bombers defeated Cincinnati’s aces Paul Derringer and Bucky Walters in the first two games of the Series. McKechnie called upon Thompson to start Game Three. It was a disaster. Charlie Keller hit a two-run homer for the Yankees in the first inning. Joe DiMaggio followed with another two-run blast in the third. In the fifth inning Keller connected for his second two-run homer of the game, and Bill Dickey knocked Thompson out of the box with a base-empty dinger. The rookie had given up seven earned runs in 4 2/3 innings. He was the losing pitcher as New York prevailed, 7-3. The Yankees also took Game Four to sweep the Series and win their fourth consecutive world championship, the first time that feat had ever been accomplished.

Thompson expressed the view that he had lost to a better team. “One of the things about the game of baseball is, when you’re overmatched, you’ve got to admit it,” he said. “That’s the way the 1939 World Series was. I don’t believe anyone was more overmatched than we were playing the New York Yankees. Those guys were absolutely awesome.”6 Many baseball experts would agree with Thompson’s assessment. The 1939 Yankees are often regarded as one of the greatest teams of all time.

In the 1940 United States census Gene Thompson and his wife Dorothy were listed as living in Decatur, Illinois, in the household of Dorothy’s father, Emery Thornell, the Macon County Treasurer.

In 1940 Thompson had an excellent season. He won 16 games, lost 9, for a winning percentage of .640, fifth best in the league, and posted an ERA of 3.32. He was used almost exclusively as a starting pitcher, the number three man in the rotation behind Derringer and Walters. With strong pitching and defense (Cincinnati set a National League fielding record with a percentage of .981), the Reds survived an injury to catcher Ernie Lombardi and the suicide of his backup, Willard Hershberger. For the first time in their long history the Reds won 100 games, as they cruised to their second straight pennant with a 12-game margin over the Brooklyn Dodgers.

In the American League the long reign of the New York Yankees came to a temporary halt. The Detroit Tigers beat out the Yankees and the Cleveland Indians in a tight race for the pennant. Led by the slugging of Hank Greenberg and Rudy York, the Tigers were a much stronger offensive club than Cincinnati, but the Reds were vastly superior in pitching and defense. No four-game sweep was expected this time; a six- or seven- game Series was anticipated. The Series lived up to expectations. The Baseball Encyclopedia proclaimed it one of the best World Series in years.7

Detroit’s veteran pitcher Bobo Newsom defeated Derringer, 7-2, in Game One. This gave American League clubs ten successive wins in World Series games. (The Yankees had won the final game of the 1937 Series and swept both the 1938 and 1939 classics.) Newsom’s father had traveled up from South Carolina to see his son pitch in the World Series. The next morning he died of a heart attack in a Cincinnati hotel room. While Newsom was attending his father’s funeral, the Reds countered with Walters in Game Two, and he bested Schoolboy Rowe to even the Series at one game apiece. Detroit gained an edge when Tommy Bridges beat Jim Turner in Game Three, 7-4. Cincinnati came back with Derringer in Game Four and this time he came through for them, defeating Dizzy Trout, 5-2. Once again the Series was knotted at two wins each.

It was widely anticipated that Cincinnati would bring back their ace, Walters, for Game Five, but McKechnie had other ideas. The night before the pivotal game, he decided to go with Thompson. As he wanted to spare the youngster pressure and let him get a good night’s rest, he kept his decision secret and didn’t announce it until just before game time on the morrow. Seated among the wives of Reds players in the box seats was Thompson’s young wife.8 Dorothy had not expected her husband to be called upon to pitch in such a pressure situation. When she heard the announcement over the stadium’s amplifier that Junior Thompson was pitching for Cincinnati, she gasped, “Oh, my God,” and passed out in her seat.

Although the Tigers got three hits off Thompson in the first inning, they were unable to score. Dick Bartell led off the frame with a single to center field and went to second on a groundout by Barney McCosky. Charlie Gehringer followed with a single to shallow center, and Bartell was thrown out at the plate trying to score. Greenberg followed with a single to left field. With runners on first and second and two men out, York ended the threat with a fly to center. In the second inning Thompson gave up a base on balls and another single, but again Detroit failed to score. In the third inning Thompson was unable to escape. After McCosky and Gehringer led off with singles, Greenberg unloaded a home run into the left field stands, and the Reds were down, 3-0. Thompson was unable to survive the fourth inning. Two walks, a sacrifice, and a two-base hit did him in. Whitey Moore relieved and fared no better. Detroit scored four runs in the frame to take a 7-0 lead. Meanwhile, Newsom, vowing to win the game for his late father, was hurling a masterpiece. He gave up only three hits as the Tigers won the game, 8-0, and took a three games to two lead in the Series.

The teams had been alternating wins in the Series, and it was Cincinnati’s turn to win Game Six. Sure enough, they did it. Walters pitched a 2-0 shutout and hit a home run as the Reds tied the Series at three games each.

Pitching on only one day’s rest Newsom faced Derringer in the deciding game. Dedicated Cincinnati and Detroit fans were pulling hard for their respective teams. Fans unattached to either contender were probably rooting for the venerable Bobo to win one more for his father and assuage his grief somewhat. It was not to be. Derringer outpitched his rival in a real pitchers’ battle, 2-1. Cincinnati won its first world championship since the tainted victory over the Black Sox in 1919.

The season of 1940 was the high water mark of Thompson’s career. Relegated to duty as a spot starter and reliever, he never again won more than six games in a season.

On July 13, 1943, Junior Eugene Thompson of Decatur, Illinois, enlisted in the United States Navy. Japan surrendered on September 2, 1945, ending World War II. Shortly thereafter on October 10, Thompson was discharged from the Navy, having served not quite 27 months.

After the war, the Reds granted Thompson free agency. He signed with the New York Giants on May 14, 1946. The Giants used him almost exclusively as a relief pitcher. In 1946 he won four games and saved an equal number. In 1947 he again won four games, but had no saves. His last major-league game came at the age of 30 on the Fourth of July, 1947, in the first game of a holiday doubleheader at Ebbets Field. Thompson’s big-league career did not end on a happy note, as the Dodgers got to him for six runs (three earned) in two innings on two hits, six walks, and two Giant errors. After this debacle the Giants sent him across the river to Jersey City, their affiliate in the Class AAA International League. Although he pitched well in Jersey, going 3-0, with a 1.45 ERA, the Giants released him on December 19, 1947. In 1948 and 1949 Thompson pitched for the San Diego Padres in the Class AA Pacific Coast League, going 8-3, with a 2.00 ERA in 1948, but slipping in 1949. His final year as a player in Organized Baseball came in 1950 when he pitched for the Sacramento Solons, the PCL affiliate of the Chicago White Sox.

In 1952 Carl Hubbell, director of scouting for the San Francisco Giants, hired Thompson as a scout, a position he held for most of the rest of his life. Gene Thompson (no longer known as Junior) scouted for the Giants for 40 years. He worked briefly for the Cleveland Indians and the Chicago Cubs before joining the San Diego Padres in 1998. He finally retired in 2005 at the age of 88.

In 1995 Thompson indulged in the old man’s privilege of saying things were better in the good old days. “In the ’30 and ‘40s, teams really were like a family. We were together nearly all the time on and off the field. We had a lot more togetherness than they have today. Players today make a lot of money, but I don’t think they have the fun we had. In my day teams were more defensive minded. Today all it seems they think of is offense. Coaches do try to teach fundamentals to today’s players, but a lot of them are so headstrong they don’t want to listen; they just want to swing from the heels and end up hitting .210 and think they’re a hell of a hitter.”9

Thompson got more accolades as a scout that he ever did as a pitcher. Eddie Bane, director of scouting for the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim said, “It was a given that when you started scouting, you just spent a few days around Gene. If you followed him around and you shut up, he’d show you all you needed to know.”10

Gene and Dorothy Thompson lived in Arizona during most of the time Gene was scouting for San Diego. He had a front-row seat at Chase Field, the home of the Arizona Diamondbacks. That club paid Thompson an honor that is surely unique in the annals of baseball. They dedicated a plaque to a scout for an opposing team. The bronze plaque is located on the wall directly behind home plate.

Junior Eugene Thompson died in Scottsdale, Arizona, on August 24, 2006, at the age of 89. He is buried in Green Acres Memorial Park in Scottsdale. His tombstone is engraved J. E. “Gene” Thompson. Dorothy, his wife for nearly 70 years, died on December 30, 2005, and lies beside him in Green Acres.

Six years in the majors, eight years in the minors, two World Series, and more than 50 years as a scout adds up to quite a baseball life for Thompson, whether we call him Junior or Gene.

Notes

1 Rick Van Blair, Dugout to Foxhole: Interviews with Baseball Players Whose Careers Were Affected by World War II. (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1994), 106.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Talmage Boston, 1939: Baseball’s Pivotal Year. (Fort Worth: Summit, 1990), 78.

5 Van Blair, 108.

6 Boston, 82.

7 Pete Palmer and Gary Gillette, eds. Baseball Encyclopedia. (New York: Barnes and Noble, 2004), 1481.

8 Van Blair, 106.

9 Rick Van Blair, “What Some Old-Timers think of the Major Leagues Today,” Baseball Digest, November 1995, 50.

10 Arizona Republic, August 25, 2006, cited by baseball-almanac.com.

Full Name

Junior Eugene Thompson

Born

June 7, 1917 at Latham, IL (USA)

Died

August 24, 2006 at Scottsdale, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.