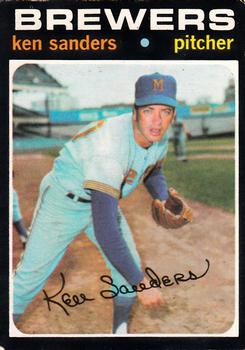

Ken Sanders

One might think a pitcher with a 29-45 career record had been something of a bust, but Ken Sanders had the misfortune to often play for losing teams. His best season is indicative of the situation: with the last-place A.L. West 1971 Milwaukee Brewers, he was 7-12 despite a major-league-leading 31 saves and an ERA of 1.91. Sanders enjoyed a long career and association with baseball after his playing days. Appearing in 409 big-league games over 10 seasons for eight different teams, he posted a very good career earned run average of 2.97.

One might think a pitcher with a 29-45 career record had been something of a bust, but Ken Sanders had the misfortune to often play for losing teams. His best season is indicative of the situation: with the last-place A.L. West 1971 Milwaukee Brewers, he was 7-12 despite a major-league-leading 31 saves and an ERA of 1.91. Sanders enjoyed a long career and association with baseball after his playing days. Appearing in 409 big-league games over 10 seasons for eight different teams, he posted a very good career earned run average of 2.97.

Sanders put in most of five seasons in minor-league ball before making it to the majors for his August 6, 1964, debut with the Kansas City Athletics.

Kenneth George Sanders Jr. was born on July 8, 1941, in St. Louis, to Kenneth George Sanders Sr. and Emma Sanders, a homemaker. His father was a police officer and detective in the St. Louis Police Department for 38 years. He had two younger brothers, who played sports in high school but didn’t carry that forward professionally.

Ken attended St. James the Greater Elementary School in St. Louis, and played both Little League and American Legion baseball. He graduated from St. Louis University High School – a Jesuit school — in 1959, where he had played baseball, soccer, and football. He was captain of both the baseball and soccer teams and was named to the All-State soccer team.

“I grew up in St. Louis,” Sanders said in a January 2018 interview, “and there was good amateur baseball at that time. Like a lot of parts of our country, there was good baseball because there were so many minor-league teams. [The major-league] teams used to have nine, 10, 12 minor-league teams. And then if guys didn’t make it, they came home and played semipro ball.”1

He put in a month attending St. Louis University, but was signed to a professional baseball contract with the Kansas City Athletics.

Ken had already drawn the attention of some “bird dog” scouts, and received a number of athletic scholarship offers. “I had it down to St. Louis University and Notre Dame. If I took the scholarship to Notre Dame, I had to play both soccer and baseball for my scholarship whereas with St. Louis, I could play either one. So, I took that [St. Louis] and I found out after one semester that I wanted to play baseball.”

Kansas City Athletics scout C. Ellsworth Brown is credited with signing Sanders. “The credit went to Ellsworth Brown, but I never had a whole lot of contact with him. That was right before the draft. There were a number of scouts that I had talked to. Of course, you didn’t have a Jeremy Kapstein at that time; there were no agents. There was a local bird dog, Dutch Snyder. He owned a hardware store, but he was a bird dog. He had a friendship with Hank Peters, who was with the Kansas City A’s at that time. That’s how that came about.

“I think my mother wanted me to sign with the St. Louis Cardinals, with me growing up there and us being Cardinal fans, but the Kansas City A’s offered me a small bonus and I had a relationship with Dutch Snyder.”

Had he not gone into baseball, Sanders had in mind at the time to study and become a medical doctor.

As a ballplayer, he wasn’t always a pitcher. “I was a shortstop/pitcher. When I did sign, there was the situation: will I be an infielder or will I pitch? I always said that I found out right away what a good curveball was. I became a pitcher in spring training.”

The Athletics assigned 18-year-old Sanders to the Sanford Greyhounds in the Class-D Florida State League for the 1960 season. He took on a heavy load, working 240 2/3 innings (many more innings than he ever worked in a season again, and many more than any young pitcher would be permitted to pitch today), starting 28 games and relieving in six others. He threw 22 complete games, and posted a record of 19-10 with a 3.22 earned run average.

He was 13-8 (3.96) in 166 innings in 1961 for the Class-A Portsmouth-Norfolk Tars in the South Atlantic League.

In 1962 he pitched for three different teams and had lopsided losing records for all three: 0-4 for Portland in the Pacific Coast League (Triple-A ball) with an ERA of 6.00; 0-3 (ERA 14.79) for Double-A Albuquerque; and 3-11 with a 4.02 ERA for the Single-A Eastern League’s Binghamton Triplets, with 11 losses coming in a row between the latter two ball clubs.

After the first of the new year, Sanders married Mary Ann Palumbo on February 9, 1963. “My grade school sweetheart – because I went to an all boys’ school. Jesuit school.” In January 2018 he said, “Still married. We’re still both healthy. We’re going to be married 55 years next month.”

His 1963 season was split between two Double-A teams, Binghamton (5-6, 3.63, with a one-hitter on August 4) and the Nashville Volunteers (1-1, 3.72). That winter he played for the Lara Cardinals in Venezuela. Lara made the playoffs and Sanders won the first game with another one-hitter. Teammate Luis Tiant followed with a two-hit shutout of his own. Lara’s season finished, he pitched for Valencia for the rest of the winter season.

Sanders had a breakout year in 1964, again in Double A but this time with the Birmingham Barons. His record, working entirely in relief at the request of manager Haywood Sullivan, was 9-1 with a 2.28 ERA. He’d learned on the job. “I got bombed…with the fastball,” he explained later. “They put me in the bullpen. I learned the slider and I became a relief pitcher…Now that I’ve learned to pitch, I don’t have the smoke.”2 Sanders appeared in 41 games and earned himself a call-up to the big leagues. The one loss for the Barons came in his final appearance , a 7-6 loss to Knoxville in which he gave up just one hit but was the victim of four unearned runs.

Sanders’s big-league debut came in the top of the eighth against the visiting New York Yankees on August 6. He saw to it that two inherited runners were stranded. In the ninth, he struck out Mickey Mantle, then got into some trouble, loading the bases before inducing a 1-2-3 double play. He worked in four consecutive games, allowing just one run (in the 13th inning of the August 8 game against the Tigers, giving him his first loss).

By the time the 1964 season was complete, he had two losses and still lacked his first major-league victory, but had 27 innings of experience in 21 games, and pitched to an ERA of 3.67.

In the winter, Sanders took some pre-law courses at St. Louis University.

The 1965 season was spent in the minors again, this time for the full year with the Triple-A Vancouver Mounties in the Pacific Coast League. Sanders worked in 57 games. He won 8 and lost 6, with a 2.74 ERA in 92 innings. It was far from his last stint in the minor leagues, though all of 1966 saw Sanders in the majors. He was drafted by the Boston Red Sox in the November 29, 1965, Rule 5 draft and opened the ’66 season in Boston.

A 12th-inning run on April 15 gave him his third career loss and an unearned run on April 23 gave him his fourth, but Sanders booked his first big-league win with 4 2/3 innings of one-hit, one-run (also unearned) relief in Yankee Stadium on April 25, an 8-5 win in relief of Earl Wilson. “I like relief pitching,” he said in May. “It gets me in so many games. If you’re a starter you get to work every fourth or fifth day. The rest of the time, you’re a spectator.”3 As the June 15 trading deadline approached, he was 3-6 with a 3.80 ERA in 24 appearances – and found himself back in Kansas City with the Athletics. He was part of a six-player trade, leaving Boston with Jim Gosger and Guido Grilli for pitchers Rollie Sheldon and John Wyatt, and Jose Tartabull.

He was 6-10 (3.75) by the end of the season. On August 27 he made his one and only major-league start, against the California Angels at Anaheim Stadium. “I had played golf all afternoon,” he said later, “and when I got to the park there was a ball in my locker. I asked who should I autograph it to? Chuck Dobson had a sore arm, and that was how they told me I was the starting pitcher.”4 He worked the first four innings, giving up four hits and just one run on a bases-loaded single in the bottom of the first. He was removed for a pinch-hitter in the top of the fifth. The Angels won, 6-5, in 11 innings.

In 1966 the A’s finished in seventh place, the Red Sox in ninth. The following year, though, saw the Red Sox first and the A’s finish last. Ken Sanders wasn’t with either team. He was back in Vancouver all year, his 2.04 ERA the best on the team for anyone with at least 60 innings pitched. His record in 50 relief appearances was 9-6.

Come 1968, the Athletics weren’t even in Kansas City. The franchise moved to Oakland. Sanders spent most of the season in Vancouver again, but was called up to the majors in July. He threw 10 2/3 innings in seven games, finishing 0-1 with an ERA of 3.38. The one loss was an 11th-inning loss in Boston.

The Athletics assigned him to the Iowa Oaks in Iowa City (American Association) for all of 1969. He started 10 games and relieved in 19 others. He was 6-7, 3.39.

On January 15, 1970, Oakland sent him and three others to the Milwaukee Brewers for two players in return. This was the first year the team was based in Milwaukee. In 1969 the franchise had begun as the Seattle Pilots but moved to Milwaukee after just the one year in Seattle. Sanders started the season once more in the minors, back in the Coast League with Portland. After 14 appearances – again working exclusively in relief – he had a 1.06 ERA (he was 4-1) when he got summoned to Milwaukee. His first game for the Brewers was on May 30. His first four decisions were wins, and he piled up saves at the same time. By season’s end, he’d earned a new nickname – “Bulldog” – and had been used in 50 games. He was 5-2 with an excellent 1.75 ERA, probably the best pitcher on manager Dave Bristol’s staff. It was Bristol who gave him the nickname, reportedly because Sanders was “so mean, tough and stubborn out on the mound.”5

Sanders had disliked the management in Oakland and was glad to have moved on. He credited Wes Stock for helping him with his approach, to not be so “cute” with his pitches and just get the ball over. He spent the wintertime performing public relations work for the Brewers.6

As noted, 1971 was Sanders’s best year, though his record was 7-12 for the last-place Brewers (69-92). He appeared in 83 games, leading the major leagues. Working as a closer in 77 games, he set a major-league record that totally eclipsed the previous mark of 67 games finished by Dick Radatz in 1964.7 Sanders threw 136 1/3 innings despite never starting a game. His 31 saves also led both leagues. His earned run average was 1.91. The number of losses was attributable in part to lack of run support in close games; 10 of his 12 losses were in one-run games. His 31 saves plus seven wins saw him contribute to 55% of his team’s victories. Unsurprisingly, The Sporting News named him “Fireman of the Year.”

In 1972, as the Brewers ran through three managers during the course of another last-place season, the closing duties were split with righty Frank Linzy, who closed 36 games to Sanders’s 51. Sanders started off nicely, working in seven games without giving up a run – earned or otherwise – and compiling four saves. But he was hammered for four runs by Boston on May 16, his ERA nudged over 3.00 on June 11, and by the All-Star break he had a record of 1-7 (3.67). In late June he was hit on the right elbow and missed two weeks. “I lost all my confidence,” he said.8 It wasn’t that he was worn out, he insisted. It was more that he wasn’t being used enough. “When I got hit hard a couple of times, they stopped using me. I’ve got to work to stay in shape and keep my edge. I don’t have any freak pitch. And you can’t keep sharp when you go out every ninth or 10th day.”9 He finished the season 2-9, 3.12.

On the last day of October, he was traded to the National League – though he didn’t pitch there until 1975. It was a seven-player trade with the Phillies that sent Sanders, Ken Brett, Jim Lonborg, and Earl Stephenson to Philadelphia for Bill Champion, Don Money, and John Vukovich. And one month later, on the last day of November, he was one of three players sent to the Minnesota Twins for Cesar Tovar. Sanders was back in the American League before he’d even been fitted for a uniform.

He was elected player representative by his Twins teammates but he did not pitch well for the Twins in 1973. He finished April, after six appearances, with an 8.00 ERA. He was 6.09 as of July 29, his last game in July, with a record of 2-4 with eight saves, and he hadn’t saved a game since June 2. Manager Frank Quilici had turned to Ray Corbin as his closer. The Twins put Sanders on waivers.

He was claimed off waivers by the Cleveland Indians on August 3 and the difference was like night and day: in 27 1/3 innings over 15 games, he was 5-1 with a 1.65 ERA.

In 1974, Sanders saw more minor-league baseball duty, appearing in only nine games for the Indians. Between April 21 and June 14, he was used just once – on May 11, when he gave up six earned runs in three innings. With an ERA of 9.82, he was released by the Indians on June 17 when the team needed to clear a roster spot as Buddy Bell came off the disabled list.

A week later, on June 24, the California Angels signed Sanders as a free agent. He was sent to Salt Lake City (Pacific Coast League) and played there until being brought up to the Angels on August 13. He appeared in nine games, closing seven of them but only working a total of 9 2/3 innings. He was without a win or a loss, with a 2.79 ERA. He saved one game, but blew one save.

Late in spring training 1975, on March 22, he was traded to the New York Mets for Ike Hampton. Sanders started the season with the Triple-A International League Tidewater Tides. He worked in 27 games, all in relief. He was 6-1 with a 1.34 earned run average. On June 29 he appeared in his first game for the Mets and stuck with them through the end of the season. For New York, he appeared in 30 games, finishing 18, and his ERA over the 43 innings of work was 2.30. He was 1-1 with five saves. There had been a real scare in the August 10 game. He had been announced as having entered the game, and was warming up to work in relief in the eighth, when a ball thrown back to him by his catcher, John Stearns, struck him in the right eye. A small blood vessel in the eye ruptured and he had to be rushed to a nearby hospital. It was the third time in two years that a Mets pitcher had been struck in the face by a baseball; the other two (Jon Matlack and Bob Apodaca) had been struck by batted balls.10 Sanders was placed on the 21-day disabled list.

In 1976, Sanders concluded his major-league playing days. He was reasonably active with the Mets, getting into 30 games and closing 18 – third on the staff in finishing games behind Skip Lockwood (44) and Bob Apodaca (18). His ERA was under 3.00 (2.87). He was 1-2 in 47 innings of work.

Suddenly, right near the end of the season, Sanders was sent back to Kansas City, purchased by the Royals on September 17. He appeared in three games. He didn’t allow a run in any of the three. But come December 13, the Royals released him.

In his 61 games for the Mets in 1975 and 1976, he’d been pitching very well, a 2.60 ERA over the two years. Why had he suddenly wound up in Kansas City? Sanders explained the story in some detail:

I really loved it in New York. Yogi [Berra was the manager and he was from St. Louis, too. At the end of that year, I was staying with in-laws in New York. The families always go home around September 1, to get the kids in school and so forth. I got a call from Joe McDonald, the general manager of the Mets. He said, “Charlie Finley called me. They’re making a run at the pennant and they want to buy you.” I said, “You know, I don’t really want to go back to Oakland. I really love it here in New York.” He said, “The deal would be you come back here in the winter. He’s going to start Rollie Fingers and you’ll be the closer.” It was like September 7. I said, “I really don’t want to go.” He asked, “Would you rather go to Kansas City? I know you’re a good friend of Whitey Herzog.” I said, “You know what? I’m not going to be eligible for the playoffs. It’s not going to be much money. The players are so cheap, they won’t give me much of a share.” He asked, “Well, what do you want?”

I was playing cards in the clubhouse. We were flying back from Pittsburgh to New York and we had this bridge game – Tom Seaver and I against Jerry Koosman and Jon Matlack. We had kind of a running game. He said, “What do you want?” I said, “I tell you what. There’s three weeks left. I’ll take 5,000. I’ll go to whoever pays me 5,000.” He said, “I’ll call the equipment manager and have him pull your suitcase off the truck. Don’t say anything to the guys ’til it’s done. I’ll call you right back.” An hour later, he called back and said, “I’ve got good news and I’ve got bad news.” I said, “What’s the good news?” He said, “They’ll both pay you 5,000.” I said, “Damn, I should have asked for 10,000.” In ’76, that was a lot of money. I said, “What’s the bad news?” “They have to win the division.” I said, “Make the ticket out to whoever’s got the lead.” Of course, I knew Kansas City had about a four-game lead at that time. So I went to Kansas City. They won it. I got my five grand. The only reason I went to Kansas City was to keep me from going to Oakland.

I told Rollie, who’s been a dear friend – we did play together in Oakland – I said, “You know, Rollie, you owe me going into the Hall of Fame. Because if I go to Oakland, you’re going to start. That’ll screw your whole career up. Maybe you’ll get hurt, and you never get in the Hall of Fame.”

That year I was going back to the Mets. They had to release me in Kansas City. I was going to go to spring training with the Mets. It’s one of those decisions. I thought, “You know what, if I can rekindle my name in Milwaukee, for business reasons and for everything else….” So I called Joe McDonald and asked him if I could talk to the Brewers. That’s how that came. I was healthy, but things just didn’t work out that spring. They decided to go to a young guy.11

On January 4, 1977, he signed as a free agent with the Milwaukee Brewers. He relieved in 30 games for Spokane (Triple-A ball in the Pacific Coast League) and then called it a day.12 He was just 2-6 with a 4.50 ERA. He saw it straightforwardly: “There’s just no future in the PCL for me and my chances of getting back to the big leagues are not good.”13 He added, “Baseball had been good to me, and it’s provided well for my family. I’ve enjoyed all 17 ½ years of it. It’s time for a change.”14

Sanders, who played in 409 games, worked all but 61 of them in the American League. As a closer, he never got to bat much. When he did, he produced little. In 67 plate appearances, he collected six base hits, all singles. He had two runs batted in, one in 1966 (off Jim Palmer, no less) that proved to be the winning run for Kansas City to beat Baltimore, 4-3, and one in 1972 that provided a final insurance run in a 5-2 Brewers win over the Indians.

He had a career .958 fielding percentage.

After leaving baseball, Sanders remained in the Milwaukee area, living in Hales Corners, Wisconsin, and went into real estate, over time becoming vice-president of corporate services for Coldwell Banker.

“When my career ended, I was healthy. I’d played over 17 years and I wanted to be home with my kids. I hadn’t been there for the first day of school…all of those things. My wife – to this day – she’s an avid baseball fan and she wishes I would have stayed in the game, but I was very fortunate in business. We had planned on moving back to St. Louis, but I had met my later business partner at a Christmas party. He had asked, ‘What are you going to do when you get through playing?’ I had to do something to make a living, and I didn’t make the money that they make today. He said, ‘Why don’t you join me and if you like it, I’ll let you buy into the company.’

“In October 1979, I bought into his company. He had three offices. Then we developed that into a bigger company and we end up becoming the Coldwell Banker franchisee in Metro Milwaukee – mortgage, title, commercial, and residential. In 1999, we sold. After we sold, I stayed one year as part of the acquisition [transition.

“Then we created a job for me for five years, with Coldwell Banker.”

Sanders also remained active in baseball circles. Sanders served on the board of the Major League Baseball Players Alumni Association for 20 years. And for 25 years he chaired the alumni association’s charity golf tournament in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin.

He also became deeply involved with the business of fantasy camp baseball. “I became friends with Ken Nigro, Charles Steinberg, and Jeremy Kapstein over the years. I actually was partners with Ken Nigro doing fantasy camps over the year. We ran things…Nigro and I did the Brewer camps for about 15 years, and then I ran the day-to-day things for the Red Sox camps with Nigro for about 10 years also. It was fun. We always had Yaz come in. I played with him part of one year in Boston, and remained friends.”

In the middle 1990s, he ran a baseball fantasy camp in Dyersville, Iowa – the very farmland that became famous as the “Field of Dreams” in the John Sayles film of the same name. The field became a popular tourist attraction and Sanders leased rights to hold the camp there from owners Don and Becky Lansing.

In 2011 baseball and real estate came together and in something of a dream assignment itself, Sanders helped broker a sale for the Lansings.15 “I kept my real estate license and then one of the most interesting things of my life was the listing and the sale of the Field of Dreams movie site. That closed the last Friday of December 2013. It’s doing quite well.”16

The Sanderses have three children – Leanne, Steven, and Laura. “Two girls, with a boy in the middle. We talk about where Fate takes us. Bud Selig has been a friend for a long time, and Wendy Selig. I’ve told Bud many times that if he wasn’t part of the acquisition team that bought the Brewers, I don’t come to Milwaukee – and we adopted two children here. I wouldn’t have those children. All three of our children are adopted. We call them ‘baseball brats’ – we adopted one in Vancouver, British Columbia, when I was playing Triple A, and then we adopted the two here in Milwaukee. We kind of did it for selfish reasons. We wanted children.”

The friendship with the Seligs almost led to another opportunity. In 2005 a newspaper story said he had thrown his hat in the ring, indicating that he would like to be considered for the position of president of the Milwaukee Brewers.17 Sanders explained, “They had a short-term president who was a friend of mine, Ulice Payne. I believe he was on the ’77 Marquette Warriors. The Warriors won the national basketball championship. A very dynamic person. He was hired, and after six months it came to an end. A local attorney called me and said, ‘I have the perfect president for the Brewers.’ I asked, ‘Oh yeah, who’s that?’ He said, ‘You.’ I said, ‘I don’t think so.’ But I met with Wendy on several occasions and I understand it got down to two of us. At the time the ball club was put up for sale and Mark Attanasio, the principal owner now, purchased it. I was trying to get Wendy to hire me before the sale but she said, ‘No, we’re going to let the new ownership make that decision.’”

There are no regrets. “Like that old saying, ‘Baseball has been very, very good to me.’ — baseball’s always been one of my passions in my life. As far as my major-league career, I always said, ‘Either everybody wanted me or nobody wanted me.’”

Eight major-league teams, and a full dozen minor-league teams, not to mention some winter league ball, but he kept plugging away. “I’ve always loved the game. I loved to play it. I wasn’t big, as you can see by my stats, but I had determination.”

He hadn’t been the kind of collector who saved a jersey from each team he played for, but presented jerseys from three of the teams to his children. “I was able to get the three from the years my kids were born. When they got engaged, I had those framed and gave them to each of them as an engagement gift. I had to do some research to get the ’68 Oakland one – that’s when the first girl was born. But there’s a guy in Chicago who is a uniform expert. He helped me find that one.”

As for Sanders, he’s remained down to earth, still living in the same Hales Corner house he had when he played for the Brewers. Asked on the telephone if that was still the case, Sanders replied, “Correct. I’m sitting there right now. I had two great years here in Milwaukee, ’70 and ’71. After the ’71, I tried to get Frank Lane to give me a two-year contract. He would not, but I figured I would be here 10 years so I bought the home. We closed in January of ’72 – and then I was traded twice that year.” Did he remember what he had paid for it? “I think it was 20-some thousand dollars.”

In 2018, Sanders says he spends most of his time in Milwaukee, but heads to Florida for a while in the winter. He keeps busy with family his priority. “I say I’m an ‘Uber grandpa.’ I have three grandkids here, and they’re into sports. One’s a freshman at Marquette University High School and he’s a hockey player so I go to all the hockey games. We go to Fort Myers for a couple of months. I’m 15 minutes from the Red Sox and five minutes from the Twins. [Paul] Molitor’s a good friend. I get to visit old friends.”

Last revised: February 22, 2018

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Sanders’ player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee. This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Notes

1 Author interview with Ken Sanders on January 3, 2018. All direct quotations come from this interview unless otherwise indicated.

2 Augie Borgi, “No-Smoke Sanders A Met Steal,” New York Daily News, May 4, 1976.

3 “Sanders Looks for Work – Finds Plenty with Bosox,” The Sporting News, May 14, 1966: 21.

4 New York Daily News, May 11, 1976.

5 Jack Pearson, “Ken ‘Bulldog’ Sanders was the First Great Brewers’ Reliever,” 50 Plus News Magazine, June 24, 2009.

6 Larry Whiteside, “Back to A’s? Rumor Shakes Sanders,” The Sporting News, November 21, 1970: 51.

7 Subsequently, that total has been topped three times, by Mike Marshall with 83 finishes in 1974 and 84 finishes in 1979, and by Bill Koch with 79 finishes in 2002.

8 Russell Schneider, “Sanders Welcomes Hearty Diet on Tribe Relief,” The Sporting News, August 25, 1973: 16.

9 Larry Whiteside, “No Balm for Sanders in Lane’s ‘Worn Out’ Alibi,” The Sporting News, September 9, 1972: 20.

10 Augie Borgi, “Sutton 3-Hits Mets, 2-1; Sanders Hit in Eye by Peg,” New York Daily News, August 11,1975: C22.

11 Sanders interview January 3, 2018.

12 “Actually, I went to Spokane as a favor to Bud [Selig]. They were going to release me and Bud said, ‘Would you go to Spokane as an insurance policy for the young kid?’ His name was Barry Cort. I told him I’d go a month. He said, ‘Don’t do anything. We’re going to make a deal.’ I stayed there for three months, until the trade deadline.” Sanders interview January 3, 2018.

13 “Sanders Bids Farewell,” unidentified newspaper clipping dated July 2, 1977 found in Sanders’ player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

14 “Coast Toasties,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1977: 40.

15 Don Walker, “Former Brews Pitcher Sanders Helps Sell ‘Field of Dreams’,” JSOnline (Milwaukee Journal Sentinel), October 30, 2011.

16 Sanders interview January 3, 2018.

17 Don Walker, “Sanders Steps Up to the Plate,” JSOnline (Milwaukee Journal Sentinel), February 9, 2005.

Full Name

Kenneth George Sanders

Born

July 8, 1941 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.