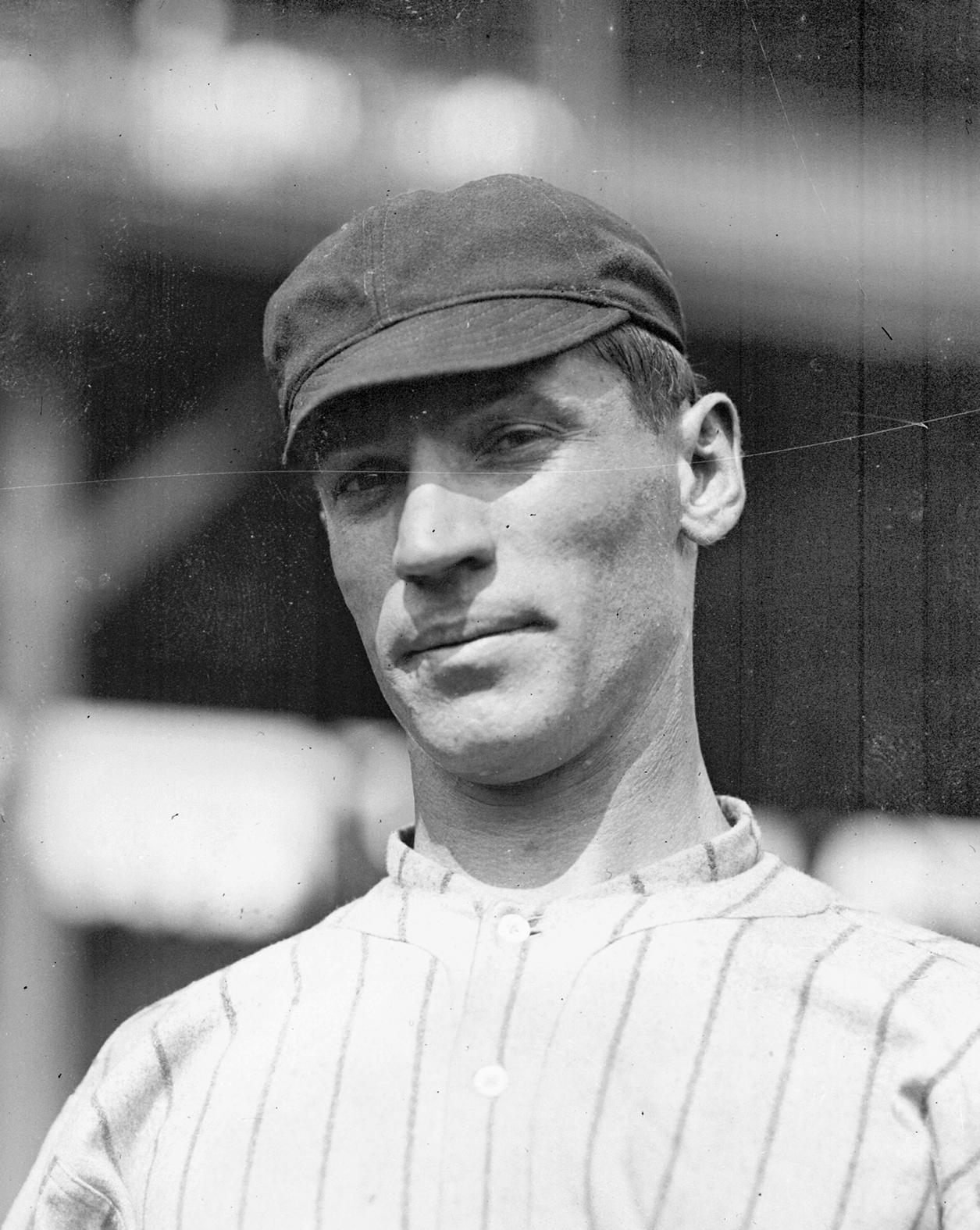

King Bader

Lore Verne “King” Bader was a lesser member of the 1918 Boston Red Sox. A right-handed hurler, he pitched in just five games, starting four and compiling an unexceptional 1-3 record. All told, Bader appeared in a modest 22 games over three major league campaigns, in 1912 (with the New York Giants) and 1917-18 (with the Red Sox), winning five and losing three. His ERA was a snazzy 2.51 in 75 1/3 innings, and he pitched memorable games against Hall of Famers Grover Cleveland Alexander and Walter Johnson. Bader’s top professional seasons came between his years of major league service, when he hurled for the Texas League Dallas Giants and International League Buffalo Bisons, and in 1920, when he was a leader on the IL Toronto Maple Leafs mound staff. His latter minor league and semi-pro careers were tainted, however, as he was accused of unfairly baffling batters with emery balls, shine balls, and spitballs.

Bader was born on April 27, 1888, in Bader, Illinois, a small railroad town. Some sources list his hometown as Astoria, Illinois, but the Bader birthplace was confirmed by his wife, Lura, in a 1973 letter to the Baseball Hall of Fame. Lura described it as “a small town very near Astoria” that was “settled by the Bader clan. An old uncle was in the logging and lumber business and through him a [railroad] spur was built…”

Bader grew to be 6 feet tall. During his career, his average weight was 175 pounds. Although a righthander on the mound, he batted left-handed. How he earned the nickname “King” is unknown, but his fondness for playing cards won him a second moniker: “Two Pairs.”

During his childhood, Bader moved with his parents to LeRoy, Kansas. Starting in 1908, he began playing for a LeRoy town team. He originally was a first baseman, but one day the LeRoy hurler failed to appear for an important game. Bader volunteered to replace him. Despite his wildness, he emerged victorious–and decided to become a pitcher.

Bader went to work as an assistant cashier in banks in Lenora and Avard, Oklahoma. “But I was too much in love with baseball to settle down to any such business,” Bader told sportswriter T.J. O’Rourke during one of his Red Sox tryouts. “My head would fairly swim after poring over account books all day and I actually dreamed of figures at night.” By August 1909, he was pitching for a town team in Lenora. An item from an unidentified newspaper, published that month, noted, “Bader who pitched a good game in the morning against Cestos, was in the box again for the afternoon game, and the way he made the Mooreland salaried players fan the air was great.”

Bader was eager to become a “salaried player.” On January 5, 1911, he signed his first professional contract, with the Independence Packers in the Western Association, a D-level minor league, and, as he recalled to O’Rourke, he “quit the bank clerking business [forever].” When the league broke up prior to the season’s end he signed with Dallas, where he compiled a 1-1 record in eight games and 45 innings.

Nineteen-twelve was a momentous year for Bader. He returned to Dallas, compiling a 16-14 record in 41 games. He surrendered 215 hits in 273 innings while walking 71 and striking out 123. On June 21, the LeRoy Reporter noted that Bader had married Lura Brutchin in Dallas two days earlier. Then on July 31, New York Giants manager John McGraw announced that the team had purchased the contracts of two hurlers, Al Demaree from Mobile of the Southern Association and Bader of Dallas. In reporting the deal, The Sporting News referred to the hurler as “‘Iron Man’ Bader, the best right-handed pitcher Dallas has this year and one of the best in the Texas League…” On August 15, the Giants played the Cubs in Chicago. “Pitcher Bader of Dallas, Texas, joined the Giants to-day, and warmed up in a Cub traveling uniform,” reported the New York Times. “He is a big, husky athlete, and showed plenty of speed.”

Bader’s big league debut came on September 30, several days after the Giants clinched the NL pennant. It could not have been much more impressive. The 24-year-old tossed a nine-hit, complete game 4-2 victory over the Philadelphia Phillies, besting Grover Cleveland Alexander, who had been vying for his 20th victory. The Boston Globe reported, “Another of McGraw’s recruits showed big league class today at the Polo Grounds….While Bader was hit hard, he always tightened in the pinches, and was at his best with men on bases.” Added the New York Times, under the headline “Giants Try New Pitcher and Win, “Lou [sic] Bader of Dallas, Texas…went to the rubber and showed that he had a backbone of steel under fire.” Damon Runyon described Bader as “a loose-jointed right-hander, who devotes himself to old-fashioned pitching. He appeared to have the limber curves expected of a young man of his occupation, and he also has quite some vapor on the baseball when he drives it through.”

Bader got into one final game that season, pitching a scoreless inning in relief on October 3 against Brooklyn, in one of the final games at Washington Park prior to the christening of Ebbets Field. His major league introduction augured well for Bader. In 10 innings pitched, he allowed just one earned run. His ERA was a snazzy 0.90. The one smudge on his record was his walk-to-strikeout ratio. He struck out three, but handed out six passes.

On December 31, the Giants announced that Bader was one of nine young pitchers invited to the team’s Marlin, Texas, spring training camp. On January 19, 1913, the New York Times ran his picture (along with those of Ferdie Schupp, La Rue Kirby, and Ted Goulait) under the headline “Young Pitchers for the Giants.” “From these four youngsters, and also Al Demaree,” the Times reported, “Manager McGraw expects to be able to pick out a couple of promising additions to his pitching staff next season.”

The Giants received Bader’s signed contract on January 18. Spring training commenced in mid-February and Bader promptly reported to Marlin, where he and his fellow rookies were tutored by Wilbert Robinson, McGraw’s assistant. On March 2, he pitched four shutout innings against Dallas. But his chance to make the team faded when he contracted measles and left training camp for two weeks. He was back by the end of the month; on March 30, he surrendered five hits in four innings’ work against Dallas. Despite his impressive debut the previous season, Bader never again pitched for the Giants. On April 9, as major league teams were finalizing their opening day rosters, McGraw announced that Bader had been released to Dallas. He was the workhorse of the Texas club’s staff that 1913 season, appearing in 46 games, tossing 308 innings, and compiling a 22-12 record. He surrendered 238 hits while walking 90 and striking out 170.

From 1914 to 1916, Bader was a leader on the pitching staff of the International League’s Buffalo Bisons, compiling records of 16-7, 20-18, and 23-8 while taking the mound for, respectively, 39, 48, and 36 games and 224, 334, and 294 innings. During his first season in Buffalo, he likely was tutored on how to toss the soon-to-be illegal emery ball. One of his teammates was Russ Ford, who is credited with perfecting the pitch in 1910.

Bader’s only opportunity to face major league batters in 1914 was in exhibition games. On March 27, he was one of three pitchers who toiled for Buffalo against the New York Yankees in Charlotte, North Carolina. Surely the highlight of his season came on opening day, when he pitched a 13-inning, complete game victory, besting the Baltimore Orioles (then an International League club), 1-0. Then on October 15, he hooked up with no less a personage than Walter Johnson. The Big Train, a native of Humboldt, Kansas, suited up with the Coffeyville nine–described in newspaper reports as “the home-town team”–and faced Bader, pitching for an Independence nine. Not only did Bader win the 1-0 contest, but he singled and scored the lone run on a three-bagger.

Despite these heroics, no big-league club considered Bader for a roster spot. But he was proving to be a steady performer at Buffalo. In an April 28, 1915, preseason game, he spun a four-hit, 3-0 victory against the Providence Grays. Similar heroics followed as the season progressed, with newspaper reports citing Bader as one of the International League’s premier hurlers.

In 1916, the hurler might have returned to the majors with the Red Sox. On January 12, Bill Carrigan, manager of the then-world champs, announced that Bader had been picked up by the team on the recommendation of Patsy Donovan, the Bisons’ skipper. The following day, the Boston Globe reported that “the chances are that [Bader] will get a good try out at Hot Springs [Arkansas].” On February 6, the day after the Bosox received Bader’s signed contract, the Globe ran a photo of the hurler under the headline, “‘King’ Bader, Latest Addition to the Red Sox Pitching Staff.”

Given his record in Buffalo, much was expected of Bader in 1916. “Manager Carrigan has confidence that Bader will show big league form this season and plans to give him a regular berth from the start,” the Globe noted. Boston Herald scribe Burt Whitman reported, “He’s a rookie here in the Red Sox camp…but [he] has the appearance and the self-possession and evidently the self-confidence of the seasoned veteran…” The headline of Whitman’s article described Bader as the “Hercules of the 1915 International league.”

But inconsistency and an injury-plagued spring training doomed his chances to stick with the big club. While warming up in the outfield prior to a March 18 exhibition, Bader severely twisted his knee. Three days later he was back on the field, pitching for the Boston regulars in a six-inning exhibition with the yannigans, and the Globe noted that he “was effective with a slow, dreamy delivery…” On March 26, the paper ran a photo under the headline “This Eleven Comprises the Pitching Staff of the Red Sox, One of the Best in Baseball.” Bader was pictured between two future Hall of Famers, Babe Ruth and Herb Pennock. But on March 29, Bader fared miserably in a six-inning contest pitting the Bosox regulars against the second-stringers. His failure was emphasized in the following day’s Boston Globe game report, which was headlined “Red Sox Jump on ‘King’ Bader.” Bader and Babe Ruth pitched for the second team. Ruth started, and limited the regulars to two hits in three innings. He was relieved by Bader, who promptly was pummeled. He also committed two errors, on a Dick Hoblitzell grounder and a Marty McHale squeeze play. “Bader’s showing was a disappointment,” the Globe wrote, “but a lame arm was undoubtedly responsible. Yesterday he showed signs of having overcome the ‘tied up’ feeling that has characterized his delivery, but today that old kink made its reappearance.”

Bader rebounded on April 11, when he and Herb Pennock combined to five-hit Boston College in a 9-1 victory. At the time, four hurlers were battling for the final spot on the Bosox pitching staff–and he was one of the odd men out. On April 19, soon after the regular season started, he was dispatched to Buffalo.

In 1916, Bader had a nifty 2.05 ERA. He pitched brilliantly that year, with a typical newspaper account of his heroics appearing in the May 4 Boston Globe, which reported that Providence “was almost helpless before Bader” in the previous day’s 3-2 Bisons victory.

In 1917, Bader finally stuck with the Red Sox. That season, with the permission of Jack Barry, the new Red Sox skipper, Bader came to Hot Springs to work out for 10 days before reporting to the Bisons’ Norfolk, Virginia, training camp. On March 23, the Boston Globe reported from Hot Springs, “Bader is here now and is looking fine,” and Barry became interested in securing the pitcher’s contract. Bader was scheduled to leave for Norfolk on March 28, but instead accompanied the Red Sox to Little Rock. Two days later, he was traded to Boston for pitcher Vean Gregg and a player or players to be named. These turned out to be infielder Bob Gill and outfielder Manny Kopp.

1917 was Bader’s busiest major league campaign. He started one game, pitched in relief in 14 others, and compiled a 2-0 record with a snazzy 2.35 ERA in 38 innings. As in 1912, his major debit was his walk-to-strikeout ratio; he gave free passes to 18 batters while striking out 14.

Bader saw his first action on May 17, when he followed Ernie Shore and Herb Pennock in a 7-1 loss to the Indians in Cleveland. The following day, he appeared in one of his more memorable major league games–if only because of the pitcher he replaced, and the streak that was halted. The Red Sox played the White Sox in Chicago. Babe Ruth, the Boston starter, had won eight straight games, but was fated to be the losing pitcher. The Babe surrendered three runs in the second inning. After he gave up two more in the third, Bader replaced him and surrendered three more runs in the sixth in the 8-2 loss.

Bader played in both games of a May 30 doubleheader against the Senators in Washington. It arguably was his finest day in the majors. In the first game, the Senators knocked out starter Ernie Shore in the eighth inning. Bader relieved with runners on second and third, retired the side and earned the save (retroactively calculated–there were no saves in 1917) in the 4-3 victory. Then he started the nightcap, surrendering six hits and eight walks in seven innings before handing the ball over to Herb Pennock in a 3-2 win. Yet again, Bader smashed a single off Walter Johnson.

Notwithstanding, Bader pitched sparingly for Boston. On August 11, the Globe reported that he had been traded to the Providence Grays for catcher Walter Mayer, but Bader remained in Boston. He was in the headlines again ten days later. In the fourth inning of an August 21 game against the Chicago White Sox, Red Sox first sacker Del Gainer was doubled off first base. He slid back into the base with one of his spikes too high off the ground to suit Chick Gandil, the White Sox first baseman. The two began jawing, with the argument continuing until later in the game when Gandil unnecessarily slid into first base. After the game, Bader and several teammates approached Gandil. Bader and Gandil began fighting and, according to the New York Times, Gandil “disposed of Lore Bader…in one round of [an] encounter on the way to the rival shower baths.” The paper added, “All accounts agree that one punch settled the argument for the rest of the season and Bader was the recipient of the punch.” He emerged with a split lip and claimed that Gandil had a ball in his right hand when he threw his punch.

Back in April, the United States had declared war on Germany and entered World War I. On December 14, 1917, Bader and Herb Pennock enlisted as yeomen in the Naval Reserve. Bader immediately reported for duty at the Charlestown Navy Yard and eventually found himself pitching for the Charlestown ball club, primarily composed of big leaguers from the Red Sox, the Boston Braves, and the Philadelphia Athletics. On May 4, 1918, Bader tossed a 12-0 shutout against the Harvard University varsity nine. His three hits were one more than he surrendered to Harvard, one a bunt single and the other a clean single. Bader’s teammates included Pennock, Rabbit Maranville, Ernie Shore, Whitey Witt, and Jack Barry, the team’s manager. On June 2 he allowed three hits in a 5-0 shutout of the Newport Naval Reserves. On June 18, he beat Holy Cross, 3-2. However, he was discharged from the Navy two days later because of a loose ligament in his knee.

Bader immediately rejoined the Red Sox, but was used sparingly. His Red Sox tenure may be summed up by the sub-heading of a Globe report on a June 28 game against Washington, which he lost, 3-1: “Pass By Bader Spells Trouble.” According to the Washington Post game report, “Bader walked Nationals at bad times. His wildness in the fourth helped the Griffs to a run and a walk in the eighth handed them another.” For the season, he had a 1-3 record, surrendering 26 hits in 27 innings while walking 12 and striking out 10 and compiling a 3.33 ERA.

On July 18, 1918, Bader played his final game for the Red Sox–and in the majors. It was a less-than-auspicious end to his big-league career. The St. Louis Browns bested Boston, 6-3, with the Globe reporting that the Brownies “found King Bader’s offerings soft picking, [as they] slammed him for 11 blows…” The game was not without some minor fireworks. In the fifth inning, Bader unintentionally hit George Sisler. The Globe reported that “the Michigan marvel before trotting to first strutted out toward the box and addressed some objectionable remarks, it is alleged, to the Boston pitcher.”

Bader then was quietly dropped from the Boston roster. He was not a part of the team during its pennant run and World Series victory over the Chicago Cubs.

In 1919, Bader was out of professional baseball, but various Boston Globe game reports in June and July recorded his pitching exploits for a local semipro team in Quincy, Mass. On July 8, in the paper’s “Live Tips and Topics” column, it was noted that Bader “turned a neat trick last Saturday down at Danielson, Conn., where he pitched against one of the mill teams. ‘King’ not only pitched a no-hit, no-run game, but fanned 22 batters…” On July 21, the Globe printed the following notice: “Quincy Baseball Club, with King Bader in the box and a record of victories over the [top] semiprofessional clubs in New England…wishes to book games away or at home in August.” Being a team’s marquee player and spinning a no-hitter is an accomplishment for any ballplayer. Only for Bader, who so recently had pitched in the big leagues, such exploits must have been bittersweet.

In 1920, Bader returned to pro baseball, playing for the International League Toronto Maple Leafs and compiling a 19-9 record with a 2.91 ERA. He appeared in 39 games, in which he tossed 229 innings, walked 77, and struck out 94. That season, a question emerged regarding Bader: Was he employing the emery ball in game situations? This issue was subtly referenced in a June 17, 1920, New York Times game report, which referred to the “failure to solve the puzzling delivery of Pitcher Bader by the Jersey City bat wielders…” Skepticism over the pitcher’s on-field ethics resulted in his being placed on Toronto’s “voluntarily retired list” for 1921-22.

Bader returned to the Boston area in 1921, where he worked in the mercantile business while pitching for the twilight league Haverhill Professionals. At this level, his walk-to-strikeout ratio was more than satisfactory. On August 4, he relieved in the third inning against Norton’s South Boston All Stars, fanning nine and surrendering no walks and one hit in an 8-7 defeat. Two days later, he struck out 12 while walking two as he bested Dorchester Town, 1-0, holding them to four scattered singles. His season was not without incident. On September 25, Bader led Haverhill to a 5-2, 10-inning victory over the North Cambridge Knights. He pitched the entire game, surrendering five hits and striking out 16. The Boston Globe reported, “The Cambridge players protested Bader’s pitching several times, claiming that he was roughing the ball. Some balls were withdrawn from the game by umpire [and former Red Sox flychaser] Olaf Henriksen.”

Bader again played ball in Massachusetts during the summer of 1922, spending May and June pitching for the twilight league St. Andrew’s A.A. of Forest Hills. By July, he had switched back to Haverhill. On July 8, in one of his best games of the season, he struck out 12 while spinning a one-hit, complete-game victory against Dorchester. Then in August, he was back with St. Andrew’s–and courting controversy. On August 15, he fanned 11 while shutting out Dorchester, 1-0. Reported the Globe, “Whether or not the contest will count in the league standings is a question, as [Dorchester] Manager Dan Leahy…protested the game in the eighth inning, declaring that King Bader, St. Andrew’s fadeaway slabster, was ‘roughing’ the ball.” Before the end of the month, he briefly pitched for Haverhill before signing on with the Sacred Hearts of Woonsocket, Rhode Island–and he must have savored the victory he earned on August 27. In an exhibition game against the Red Sox, played in Woonsocket, he bested his former team, 5-3, in a rain-soaked seven-inning complete game triumph. Bader’s elation might have been tempered by the Boston Globe game report. The paper noted that, “although the Red Sox hit the ball often, it usually went right at the infielders.”

On September 17, Bader hurled a complete game for the Sacred Hearts in an exhibition against the Boston Braves, also in Woonsocket. While he was the losing pitcher, the final 2-0 score was more than respectable. But again, the Globe report of Bader’s effort was less than complimentary: “King Bader, although allowing the Braves but seven hits, was wild in the early innings, but pulled out of several bad holes.”

In 1923, Bader “unretired” and rejoined the Toronto Maple Leafs, compiling a 3-1 record in seven games and 47 innings. Throughout his minor league career, his walk totals were high but never more than his number of strikeouts. Now, the aging hurler–he was 35 years old–walked 20 while striking out 13.

His tenure in Toronto ended in controversy. During his time with the Maple Leafs, newspaper reports hinted that he was doctoring his pitches. On June 2, he pitched against the Rochester Tribe, and the Chicago Tribune reported that manager George Stallings had complained about Bader’s “alleged ‘shine ball’ delivery.” The skipper even promised to protest any future game in which Bader pitched against his team. As proof, Stallings produced several of the balls he claimed Bader had used; reports vary as to whether Bader employed them only in this game or in several recent contests.

While the matter was under investigation by International League officials, Bader abruptly quit the Maple Leafs and returned to Boston. On June 6, the Syracuse Herald noted that the constant skepticism by rival teams “may have been the reason he decided to quit organized ball after only having been reinstated this year.” Bader finished the summer playing twilight league ball for the Sacred Hearts–and his reputation preceded him. He was dubbed a “Shine Ball Outlaw” and “Shine Ball Artist” in the headlines of articles appearing in June issues of the Fitchburg Sentinel. On June 15, the paper claimed that Bader “is barred out of the big leagues because of a freakish delivery and whose shine ball only recently caused a wrangle in the International league…” Ten days later, the Sentinel reported that “Speed” Shea, a St. Andrew’s pitcher, was a Bader protégé–and the veteran “is teaching the youngster how to get away with the spitter and the shine ball.”

In 1924-25, Bader continued pitching in the Boston area and coached a semipro team in East Douglas, Mass. A February 17, 1930, New York Times article cited him as the mentor of Bump Hadley, then an up-and-coming major league hurler who played in East Douglas prior to his 1926 debut with Washington. There was no mention of Bader counseling Hadley on how to scuff his pitches.

In March 1926, Bader was hired as a coach for the Boston Braves. After spring training, he was offered a job as pitcher-manager of the New England League Lynn Papooses. He hurled 102 innings, compiling a 6-3 record and 2.64 ERA. On June 30, the Daily Kennebec Journal of Augusta, Maine, described Bader as the “hurling ace of the Lynn team,” but quickly added that the 38-year-old “is not so young and spry as he was ten years ago.” The paper also reported that Bader “is said to be resorting to nicking the ball and this fad has resulted in the throwing out of a few horsehides in Lewiston and other places.”

Bader then became a Boston Braves scout. His assignment was to scrutinize promising minor leaguers from New York to the Midwest and Texas. In 1928-29 he returned to the field, managing the Providence Grays (which had become an Eastern League franchise). He also concluded his playing career as he pitched briefly during these seasons, appearing in seven games and winning one without a loss. As a minor league hurler, Bader compiled a respectable 124-72 record. At the end of the 1928 season, Providence scribe Frank Wakefield described him as “still a better twirler than one or two of the moundsmen collecting wages here…”

In 1930, Bader managed the Eastern League Hartford Senators. He was out of professional baseball the following year but returned in 1932 for one final fling as a coach for the American Association Milwaukee Brewers.

Starting in the mid-1930s, Bader was employed as a WPA manager in Coffey County, Kansas. (The WPA, or Works Project Administration, was a Depression-era jobs program.) According to a 1938 report in The Sporting News, he also operated a baseball school in Emporia, Kansas. Primarily, he spent the rest of his working life as a farmer. He and Lura purchased a farm near LeRoy, where they remained until 1955 before moving into a new house in town. For decades, Bader was active in LeRoy’s Neosho Masonic Lodge No. 27, and served as district deputy grand master and grand marshal of the Grand Lodge of Kansas A.F. & A.M. Masonic Temple.

A June 22, 1962 news item in the LeRoy Reporter noted that Lore and Lura Bader were about to celebrate their golden wedding anniversary. “Modern players,” exclaimed the old hurler, “are on the ‘sissy side’ when they protest that pitchers are throwing at them.” Six years later, prior to yet another wedding anniversary, Bader lovingly cited his wife while observing, “We sure have had a wonderful life together.”

During the early months of 1973, Bader began preparing his baseball mementoes for donation to the Baseball Hall of Fame. They included a ball autographed by Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig and a scrapbook, loaded with newspaper clippings charting his career, which had been presented to him by Providence Evening Bulletin sportswriter Bill Perrin. The scrapbook was inscribed, “To my friend Lore V. ‘King’ Bader…with whom I passed many pleasant moments during the Eastern League campaign of 1928.”

On March 22, Lee Anthony of LeRoy penned a letter in which he solicited the Hall of Fame’s interest in Bader’s memorabilia. Anthony noted that the aged pitcher suffered from glaucoma and was totally blind, and reported that he had once roomed with Babe Ruth. In a follow-up note, dated April 17, Lura Bader observed that the scrapbook “can tell you more about L.V.’s…baseball days than I can.” The book and the ball arrived in Cooperstown on May 14.

Bader died quietly in his sleep just over two weeks later, on June 2. He was 85 years old, and was survived by his wife; a brother, Max; and a sister, Ethel; he was predeceased by a brother, Dr. Jesse Moren Bader, the first president and general secretary of the World Convention of Churches of Christ, an evangelical organization. The Baders had no children.

During his later years, Bader savored reminiscing about his baseball career. In his obituary, published in the LeRoy Reporter, it was noted that from him “came a rich store of experiences which have made joyful listening for his friends over the past half century.”

Bader was buried in LeRoy Cemetery. It is a shame that the old pitcher played for the Giants and Red Sox, rather than Yankees. His funeral service was held at LeRoy’s Mattingly Funeral Home. Its proprietor was named Don E. Mattingly.

Sources

In preparing this biography, I consulted news items on Bader that appeared in the Boston Globe, Boston Herald, New York Times, Chicago Tribune, Providence Evening Bulletin, Syracuse Herald, Washington Post, Fitchburg Sentinel, Daily Kennebec Journal, LeRoy Reporter and The Sporting News. The aforementioned scrapbook proved a treasure trove of information. Also helpful were Bill Nowlin, Dick Thompson, Tim Wiles, and Claudette Burke of the Baseball Hall of Fame, and Brad Bisbing of the Buffalo Bisons.

Full Name

Lore Verne Bader

Born

April 27, 1888 at Bader, IL (USA)

Died

June 2, 1973 at Le Roy, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.