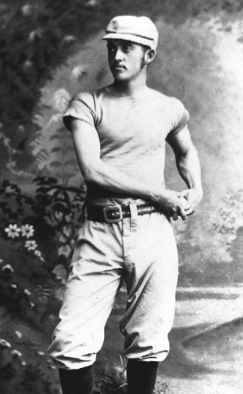

Lee Richmond

J. Lee Richmond, major league baseball’s first full-time1 left-handed pitcher; is best known for pitching the first perfect game. He also accomplished a number of other noteworthy firsts during his six-year major league career. Because he played concurrently as an amateur and as a professional, the first rules were promulgated that banned a professional from participating in amateur sports. His heart-side delivery caused changes in baseball strategy that are integral to every game played today.

J. Lee Richmond, major league baseball’s first full-time1 left-handed pitcher; is best known for pitching the first perfect game. He also accomplished a number of other noteworthy firsts during his six-year major league career. Because he played concurrently as an amateur and as a professional, the first rules were promulgated that banned a professional from participating in amateur sports. His heart-side delivery caused changes in baseball strategy that are integral to every game played today.

Lee Richmond was the last of nine children and the last of six sons of Cyrus R. Richmond, a Baptist minister, and Eliza (Tinan) Richmond. He was born May 5, 1857, in Sheffield, Asthabula County, Ohio. He attended public and normal schools in Geneva, Ohio. Richmond enrolled in the (college) Preparatory Department of Oberlin College of Ohio as a sixteen-year-old in 1873. His three-year Oberlin experience focused mutually on education and baseball—a combination that he would employ for a decade. He followed Willis, an older brother by seven years, as a member of Oberlin’s baseball club and pitched for the college nine.

He enrolled at Brown University in 1876, performing in the fall season as an outfielder for the varsity nine and playing occasionally for the Rhode Islands of Providence. Richmond was elected class president, played on the school’s first football team and spent the next two seasons as an outfielder and pitcher for Brown. He labored in Brown’s gymnasium the winter of 1878-1879, developing several curve deliveries. His curves broke up and down, rather than in and out and were known as a jump ball and a drop ball. Combined with his rare left-handed delivery the pitches produced devastating results. Richmond, slight in stature at 5 feet 10 inches and 142 pounds, did not overpower hitters and consequently allied his unusual pitches with cunning, deception and strategy. He studied hitters and kept a book on them.

Richmond burst upon the baseball scene in 1879. He held the Chicago White Stockings hitless in his professional debut, led his Brown University nine to the college championship, pitched a professional no-hit game and made his major-league debut. He ended the season as he began it, playing as an amateur and captaining Brown’s team. His composite record for the 1879 season included 47 wins and a .350 plus batting average. After much entreating by manager Frank Bancroft, Richmond agreed to pitch an exhibition game for Worcester of the National Baseball Association against Cap Anson’s White Stockings on June 2. He was paid $10.00 for the appearance and so became a professional baseball player on that day.

In the game, Richmond walked the first Chicago batter and then did not allow another base runner as Worcester prevailed 11-0 in 7 innings. Following the contest Anson and Bancroft both sought to make a contract with Richmond. Bancroft closed the deal for $100 per month. One week later, Richmond rejoined his college mates for the college championship game against Yale and again prevailed. He struck out the final Yale batter with runners on second and third in the ninth inning to preserve a 3-2 win in what Ronald A. Smith described as “one of the great college games of the nineteenth century” in his Sports & Freedom: The Rise of Big-Time College Athletics. Back in the professional ranks, he threw a two-hitter against the Washington Nationals, the leaders of the National Baseball Association, on June 11. On July 28 he no-hit Springfield and contributed four hits himself as Worcester romped 14-0. Still participating in Worcester’s and Brown’s fall schedules, Richmond was retained by Harry Wright of Boston (NL) to pitch his team’s season finale. After a shaky first inning against Providence, he pitched a solid 12-6 win allowing but a single base hit over the final eight innings. He recorded a league record five consecutive strikeouts in his National League debut.

Since Richmond had played concurrently as an amateur and professional, his eligibility was the focus of the December 1879 meeting of the American College Base Ball Association (Amherst, Brown, Dartmouth, Harvard, Princeton, and Yale). After lengthy discussion, the body agreed to allow Richmond (and his Brown catcher Winslow) to play but banned future professionals from participating. Still smarting from its losses to Brown and Richmond in the previous season, Yale walked out of the meeting in protest and later withdrew its membership. This rule continues as the basic tenet of amateurism for virtually all sports worldwide.

Richmond’s remarkable 1879 season so revitalized the Worcester franchise that the small New England city was admitted to the National League for 1880. According to The Toledo Blade Richmond signed with Worcester (NL) for a record $2,400 in 1880. He pitched the entire three-year history of the Worcester franchise, accounting for 80 percent of the club’s wins. He pitched and played the outfield for the Providence Grays (NL) in 1883 and briefly for the Cincinnati Red Stockings (AA) in 1886. Besides being the first truly successful left-handed pitcher in major league baseball, Richmond established a number of initial milestones. He gave up the first grand slam home run, won 20 games for a last-place team and contributed a home run to the first three- home-run inning and four-home-run game for a team. He was the first left-hander to win 30 games for a season. He pioneered the use of a variety of pitches that included a rising fastball, a drop ball and a change of pace. The milestone event of Richmond’s career came on June 12, 1880 when his perfect game, another first, beat Cleveland 1-0 at Worcester. Richmond’s left- handedness caused teams to stack their right hitting batters at the top of the lineup and left-handed batters to cross over when facing him as baseball very quickly adapted to the left-handed pitcher. Worcester’s manager, Frank Bancroft, also instituted new pitching strategies when he alternated Richmond and right-hander Fred Corey according to which box a batter used. The game adapted quickly.

A perfect game is the rarest of single-game pitching feats. Taken in context with the events preceding the game, Richmond’s gem was even more unlikely. Two days before this Saturday contest Richmond had shut out the Clevelands 5-0. He was in the midst of a streak of 42 consecutive innings during which he would not allow an earned run, and the perfect game would be his third shutout in nine days. He returned to Worcester for graduation festivities and parties, passing up the Worcester’s Friday’s exhibition game with the Yale nine. Graduation events included a class baseball game played at 4:50 a.m. on Saturday. Richmond had been up all night following the class supper at Music Hall. He took part in the ballgame and went to bed at 6:30 a.m. He rose in time to catch the 11:30 a.m. train for Worcester to pitch in the afternoon contest against Cleveland. The train on which he rode was delayed, and he was forced to go to the field without his dinner. So, his preparations for the game included forgoing food and sleep and playing another game earlier in the day.

Richmond and Cleveland’s Jim McCormick locked up in a duel. Richmond himself got the first hit of the game in the fourth but was erased on a double play. Worcester got but two more hits on the day, both by shortstop Art Irwin. The only run of the contest scored in the fifth on a double error by Cleveland second baseman Fred “Sure Shot” Dunlap. Like so many classic games, this one featured a game-saving play. In the fifth inning, Cleveland’s Bill Phillips hit a ball through the right side for an apparent base hit. Lon Knight, captain, right fielder, and old man of the team at age 26, charged, scooped up and fired to first. Umpire Foghorn Bradley called the runner out, and the perfect game was preserved. It was Richmond’s third professional no-hitter before he graduated from college.

Richmond always kept his achievement in perspective. He once remarked in a newspaper interview that catcher Charlie Bennett and the boys behind me gave me perfect support.” On another occasion he said, “I couldn’t have pitched it if the fielders had not been so expert in handling the ball.” Richmond knew that an errorless game played by barehanded fielders was a rare achievement in itself. The game was called “the most wonderful on record” by one writer and “unprecedented” by another as the phrase perfect game had yet to be coined. However, several contemporary newspaper accounts referred to perfection in describing the play. The Worcester Daily Spy commented, “Richmond was most effectively supported, every position on the home nine being played to perfection.” The Chicago Tribune said in part, “The Clevelands were utterly helpless before Richmond’s puzzling curves, retiring in every inning in one, two, three order, without a base hit. The Worcesters played a perfect fielding game.”

The ballplayer-student graduated from Brown University with a Bachelor of Arts degree on June 16, 1880, four days after his perfect game. He continued his education over the next three winters at The College of Physicians and Surgeons (now Columbia University) and the University of the City of New York (now New York University) and at medical facilities in Providence and New York City. His M.D. was conferred by University of the City of New York in March of 1883. He was awarded a Master of Arts degree in June of 1883 by Brown University. When he stepped on to the field for Providence (NL) in 1883, he became the first physician to play major league baseball. For ten years it was baseball in the summer and school in the winter for J. Lee Richmond. Presumably his baseball earnings provided him means to pursue his bachelor’s and advanced degrees. Following the 1883 season the tandem vocations ended when he hung up his spikes, shelved the books, and went about the business of his life’s work.

The Worcester franchise ceased to exist following the 1882 season, and Richmond signed with the National League’s Providence Grays for the following season. His pitching successes had diminished over the course of his career, and he was now primarily an outfielder but was in the box occasionally for the Grays. His opposite-side delivery and repertoire of pitches that had so surprised hitters when he first appeared on the scene had been combated by new strategies and familiarity. As was the custom of the day, Richmond was a virtual one-man pitching staff for the Worcesters, and he experienced arm problems as overwork took its toll on his slender frame. A rule change also affected Richmond’s delivery. The pitching distance was changed from 45 to 50 feet beginning in 1881. These factors combined to reduce his effectiveness but he continued in the game in another role and until he was ready to leave baseball.

Following the 1883 season, Richmond continued his medical study with Dr. C. T. Gardner in Providence and then returned to his native northeast Ohio, where he established his own practice. He used his vacation in 1886 to make a short and unsuccessful comeback with Cincinnati (AA). He continued his medical practice in Conneaut, Ohio, until changing careers and becoming the principal of the Geneva, Ohio, schools in 1889. He moved west to Toledo in 1890 to become a teacher at Toledo High School. He continued his career in education in Toledo for nearly forty years. In Toledo high schools he was a teacher of Greek, history, physics, chemistry, and mathematics, a baseball coach, an orchestra conductor and a principal. The son of Addie Joss, the pitcher of baseball’s fourth perfect game, was in Richmond’s geometry class at Scott High School. According to The Toledo Blade, Richmond told young Norman Joss upon their first meeting, “Your father pitched a perfect game. Well, so did I. It doesn’t mean anything around here and it isn’t going to help you with your geometry.” In 1921, at age 65, he was forced to “retire.” He then became Professor of Hygiene and Dean of Men at The University of the City of Toledo (now The University of Toledo). He remained at the university the rest of his years.

Richmond was a lifelong baseball fan and appeared in uniform in his late sixties at Toledo’s Swayne Field. His perfect game gave him a kind of celebrity status in Toledo, and his baseball prowess was mentioned many times over his years in the city. He was the first Brown University athlete named to that school’s Athletic Hall of Fame. He enjoyed golf throughout his life and was a scratch player.

J. Lee Richmond married Mary Naomi Chapin, his former high school student, on December 27, 1892, and had three daughters, Ruth, Dorothy, and Jane. He died at age 72 on October 1, 1929, and is buried in Forest Cemetery in Toledo, Ohio.

Sources

Brownlee, Kimberley, “The Most Wonderful Game: J. Lee Richmond’s Perfect Game.” In Timeline, Vol 21, No. 3, edited by Christopher S. Duckworth, Columbus OH: The Ohio Historical Society, 2004.

Goslow, Brian Charles, “Fairground Days: When Worcester was a National League City.” In the Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 19, No. 2, edited by Martin Kaufman,Westfield, CT: The Historical Journal of Massachusetts, 1991.

Husman, John Richmond, “Baseball’s First Perfect Game.” In Toledo Magazine, Toledo OH: The Toledo Blade, May 16, 1987.

______. “J. Lee Richmond.” In Nineteenth Century Stars, edited by Mark Rucker and Robert L. Tiemann, Kansas City, MO: The Society for American Baseball Research, 1989.

______. “J. Lee Richmond’s Remarkable 1879 Season.” In The National Pastime Vol. 4, No .2, edited by John Thorn, Cooperstown, NY: The Society for American Baseball Research, 1985.

Mayer, Ronald A., Perfect! Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc.,1991.

Richmond, J. Lee, “Beating Harvard and Yale in Seventy-nine.” In Memories of Brown, edited by Robert Perkins Brown,, Henry Robinson Palmer, Harry Lyman Koopman and Clarence Saunders Brigham, Providence: Brown Alumni Magazine Company, 1909.

Smith, Ronald A., “Lee Richmond, Brown University, and the Amateur-Professional Controversy in College Baseball.” In NEQ 64 March 1991.

Smith, Ronald A., Sports & Freedom: The Rise of Big-Time College Athletics New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

The Brunonian

Chicago Tribune

General Catalogue of Oberlin College 1833-1908

J. Lee Richmond file, National Baseball Library, Cooperstown, NY

New York Clipper

New York Tribune

The Toledo Blade

The Toledo News Bee

Worcester Daily Spy

Worcester Evening Gazette

Notes

1 Bobby Mitchell pitched in 45 games mostly for Cincinnati from 1877-1882, but was never his team’s primary pitcher.

Full Name

J Lee Richmond

Born

May 5, 1857 at Sheffield, OH (USA)

Died

October 1, 1929 at Toledo, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.