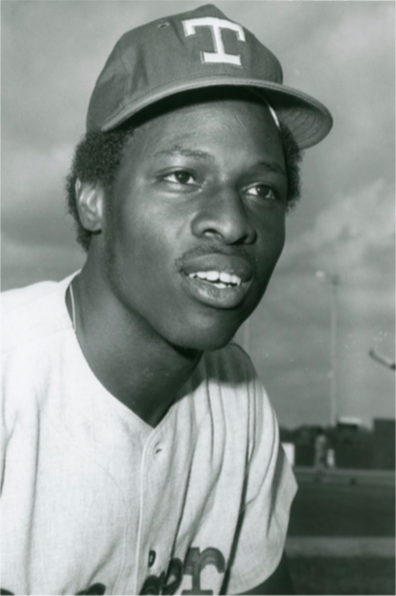

Lenny Randle

MLB Network produced a television special calling versatile switch-hitting infielder-outfielder Lenny Randle “The Most Interesting man in Baseball.”1 The 12-year major-league veteran learned to speak five languages; wrote, published, and performed a hip-hop song;2 worked as a stand-up comic for free steaks; was principally responsible for the popularity of baseball in Italy; and ran a baseball academy in California, Italy, and other locales in Europe.

MLB Network produced a television special calling versatile switch-hitting infielder-outfielder Lenny Randle “The Most Interesting man in Baseball.”1 The 12-year major-league veteran learned to speak five languages; wrote, published, and performed a hip-hop song;2 worked as a stand-up comic for free steaks; was principally responsible for the popularity of baseball in Italy; and ran a baseball academy in California, Italy, and other locales in Europe.

Lenny’s father, Isaac Randle, was a longshoreman and a veteran of World War II. Isaac’s wife, Ethel, helped with the finances by working as a seamstress for various families in the Southern California community where they lived. During the war, Isaac met a French chef while stationed in the Anzio-Nettuno region of Italy, who introduced him to the delights of European food. He promised the chef, out of gratitude for his friendship and wonderful meals, that if he ever had a son he would give him his name, Schenoff. After the war, Isaac fulfilled that promise as Leonard Schenoff Randle came into this world in Long Beach, California, on February 12, 1949. Isaac and Ethel’s family eventually grew to eight: four boys and four girls. The parents emphasized education, and all eight of the Randle children obtained college degrees.

Growing up around the stories of his father’s military experiences and later playing with military veterans like Ted Williams, Billy Martin, and others provided Lenny Randle with a perspective of dedication, sacrifice, and appreciation of life itself that perhaps combat experience helped provide. Randle reflected that Williams, in the clubhouse, would talk about hitting, fishing, and war. These stories fascinated and illustrated how these players took a military approach to playing baseball: “Those guys played baseball as if it was war. Each game brought the intensity of combat. You played a game as if it was the last game on earth and you were getting taken over by another country. We were not concerned about our batting averages. It was about the team and winning the game. That’s how I learned to play the game.”3

Randle grew up in Compton, California. At Centennial High School he was a star athlete in football and baseball. In 1967, his senior year, was captain of both teams. Drafted by the St. Louis Cardinals in the 10th round of the 1967 amateur draft, he chose to attend Arizona State University to further hone his baseball skills under the venerable Sun Devils coach Bobby Winkles. Despite his slight 5-foot-10 and 169 pounds, Randle continued to be involved with football. Seeing action as a wide receiver in the 1969 season, he was credited with five receptions for 65 yards and one touchdown. His real contribution was as a kickoff and punt-return specialist where his speed was best utilized.

Randle’s presence on the ASU baseball team was much more impactful; he batted .298 as the starting shortstop in 1968, .225 at second base in 1969, and .335 at second base in 1970. The highlight of Randle’s college baseball career was the 1969 season. The Sun Devils went 56-11, leading the Western Athletic Conference, defeating Brigham Young and Idaho in the conference tournament, and advancing to the College World Series. After losing, 4-0, to a 33-4 Texas Longhorns team that included Burt Hooton and James Street, the Sun Devils won their next five games to claim the College World Series title. In Randle’s final season, 1970, the Sun Devils fell to a 30-22 record and missed qualifying for the playoffs. That disappointment was soothed for Randle when the Washington Senators drafted him in the first round of the 1970 amateur draft, the 10th player selected.

The 21-year-old switch-hitting infielder signed immediately and was assigned to the Denver Bears of the Triple-A American Association. Playing in 34 games at second base, Randle batted .208. Back at Denver in 1971, he had played in 48 games, mostly at second base and was batting .288 when he was called up to the Senators and made his major-league debut on June 16, 1971.

A tough assignment it was, for Randle’s first game was against first-place Oakland with Vida Blue, 13-2 at the time, on the mound for the A’s. Playing second base and hitting seventh in the lineup, Randle flied out to left field in his first at-bat, in the top of the second inning. After being called out on strikes in the fifth inning, Randle got his first major-league hit, an infield single, when he beat Bert Campaneris’s throw to first from deep in the hole at shortstop in the seventh inning. He batted again in the top of the ninth and struck out swinging to end the game. Blue pitched a complete game and the A’s prevailed, 5-1.

Randle played in 1,137 more games, for the Senators, Texas Rangers, New York Mets, New York Yankees, Chicago Cubs, and Seattle Mariners. His 12-year career included standout performances in 1974 with the Rangers and 1977 with the Mets, hitting .302 (sixth in the American League) and .304 respectively.

Randle was a gifted, athletic player both in positional flexibility and durability. Seldom injured, he played in an average of 143 games per year over a five-year span from 1974 through 1978. Though principally an infielder, Randle also was a valuable insertion into the outfield, starting 60 games there in 1975, mostly as the center fielder, recording eight assists and four double plays from that position. In that same year he caught six innings. His speed on the basepaths was reflected by 199 stolen bases in the five-year span.

Drafted as a seasoned college player, Randle never played below Triple-A ball in the minor leagues. After getting his feet wet in 46 games with Denver in the American Association in 1970, he began the 1971 and 1972 seasons at Triple A but was called up to the major-league club by the middle of each season. A solid 1973 season of 140 games with Spokane in the Pacific Coast League, where he stole 39 bases and hit .283 with an on-base percentage of .373 clearly showed Randle was ready for full-time duty in the big leagues.

Though Randle eventually played for six major-league teams, he knew only one franchise from 1970 until April 26, 1977, the Washington Senators/Texas Rangers. In ’77, after a highly publicized incident in which he assaulted his manager, he was traded to the New York Mets, where he enjoyed his best year, batting .304 with 33 steals in 136 games in 1977. But the 1978 season saw his batting average sink to .233 with only 14 steals in 132 games. On March 29, 1979, at the end of spring training, Randle was released by the Mets. For Randle, 1979 became a whirlwind odyssey of associations with two minor-league teams and four major-league clubs who sent him to the minors in May and returned him to the majors by August.

On May 16 of that year, Randle signed a minor-league contract with the San Francisco Giants and was assigned to the Phoenix Giants of the Pacific Coast League. On June 28 he was included in a trade that returned the Giants’ Bill Madlock to the Pittsburgh Pirates. The Pirates assigned Randle to their Portland PCL affiliate, where Randle played until his contract was purchased by the New York Yankees on August 3. He was with the Yankees for the remainder of the season. Let go by the Yankees after the season, Randle finished his career with the Chicago Cubs and Seattle Mariners.

Randle’s major-league career involved more than just statistics. It was sprinkled with circumstantial oddities that worked over time to support an image of someone who just “bumbles” through life. In fact, in the MLB Network Presents show about Randle he is referred to as the “Forrest Gump of baseball.”4 That was a reference to an innocent, childlike person who is exposed, shaped, and controlled by life’s circumstances as opposed to a person of intelligence and maturity who shapes and manages his own life. Consider these unusual circumstances:

Since 1971, five major-league baseball games have ended in a forfeit. Randle played in two of them. The first was on the last day of the 1971 seasons when fans stormed the field with two outs in the ninth inning, angry over the team’s decision to move the franchise to Texas in 1972. In 1974 he played in the infamous Ten Cent Beer Night game in Cleveland when drunken fans began to come on the field. While with the Mets, Randle was at bat on July 13, 1977, when the lights went out in New York City. Shea Stadium lights failed around 9:30 P.M. with Randle at bat and the Cubs’ Ray Burris on the mound. Randle would claim years later that he had just hit the ball between third and short for a single when the darkness descended so it was never scored officially. This was the second game of a scheduled three-game series. When the game was resumed, 64 days later, on September 16, a scheduled offday, Randle did hit the ball toward the shortstop and was thrown out at first.

Randle’s public image threatened to be defined by two other incidents that occurred during his playing career.

On May 27, 1981, Amos Otis of the Kansas City Royals hit a dribbler down the third-base line. As it rolled along the baseline, Randle, on his hands and knees, blew the ball into foul territory. After much consultation, the umpires ruled his action illegal. (This act was repeated on a bunt down the third-base line in 1987 by Royals third baseman Kevin Seitzer. On that occasion, he was unsuccessful in making it go foul.) Randle’s antics have been portrayed as evidence of his being unconventional, weird, crazy, and strange. One might suspect such labels were solidified when viewing yet another side of Randle from an event that took place on March 27, 1977, before a spring-training game in Orlando, Florida.

This is the well-known attack by the 28-year-old Lenny Randle on his 49-year-old manager, Frank Lucchesi. After holding down the Rangers’ second-base position for 113 games in 1976, Randle was told he would lose that position in 1977 to another first-round pick from Arizona State, Bump Wills, an unseasoned rookie with only two minor-league seasons on his résumé.5 When Randle complained, Lucchesi expressed surprise that someone so well paid and fortunate enough to be a major-league ballplayer should complain about such matters and went further, calling Randle a “punk.” The on-field confrontation turned violent with Lucchesi suffering a broken jaw before the “fight” could be stopped by teammates. Randle was suspended, fined, and traded to the Mets. In a pair of ironically related events, the Rangers in 1977 enjoyed their best season to date with 94 wins and a second-place finish to the Kansas City Royals in the AL West. And Randle went on to enjoy his best season, hitting .304 in 136 games for the Mets. The lights may have gone out at Shea Stadium in 1977 but Lenny Randle shined brightly in the midst of a gloomy season of 98 losses for the Mets.

Randle’s major-league career came to an end in 1982, at the age of 33, while he was with the Seattle Mariners. On June 18 he pinch-hit for Paul Serna, the Mariners shortstop, in the ninth inning and lined a single to center off Kansas City reliever Dan Quisenberry for the 1,016th hit of his major-league career. On the 20th, he was a ninth-inning defensive replacement at second base and didn’t come to bat. On June 28, he was given his unconditional release by the Mariners. And thus was born the second life of Lenny Randle.

At the urging of Ted Williams and some friends in the military, Randle was encouraged to try a year of Italian baseball. In the spring of 1983, he became the regular second baseman for Nettuno of the Italian Baseball League and enjoyed great success, winning that season’s batting championship with a audy average of .477.6 He was the first major-league player to compete professionally in Italy. It was love at first sight for Lenny and he soon had his whole family brought over to live there. He was affectionately known as “Cappuccino” because of his seemingly endless energy and reliance on little sleep each night. He said, “After I die there will be plenty of time to sleep. While I’m here, two to four hours is plenty!”7 In a Rolling Stone posting in 2015 Randle said, “I’m blessed and staying away from stress. It’s the Fountain of Youth here. This is home to me. It’s like utopia!”8

Randle, his wife, Linda, and sons Kumasi, Ahmad, and Bradley seem to have ventured into many different areas of life. Bradley enjoyed a brief fling in the NFL and the Canadian Football League after starring in football at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas. A cousin, Marques Johnson, played in the NBA. The eight Randle siblings own a nonprofit service that helps students discover and apply for college scholarships.

In 1980, Randle was elected to the Arizona State University Sports Hall of Fame for his football and baseball contributions.9 The citation mentioned his major-league career, and noted that as a football return specialist, he scored six touchdowns on kickoff and punt returns.

Randle travels frequently to Italy, where he promotes and conducts baseball clinics, and searches for that next Joe DiMaggio. He remains convinced that it is only a matter of time until some 10-year-old, receiving instructions at his baseball academy, grows into the first super star major-league ballplayer from Italy.

Randle was asked in an interview how he viewed his life. His surprising answer was, “I don’t really think about it. I just do it! I live every day as if it was my last day on earth.”10

Postscript

Randle died at the age of 75 on December 29, 2024.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com and the following:

Kantowski, Ron. “Frenetic Father Relishes Randle’s Breakthrough,” Las Vegas Review-Journal, November 4, 2012.

Miller, Mark. blitzweekly.com/lenny-randle-still-crazy-years/.

Stephen, Eric. sbnation.com/mlb/2015/12/11/9887920/lenny-randle-documentry-mlb-network-review.

Notes

1 MLB Network, MLB Presents: Lenny Randle, “The Most Interesting Man in Baseball,” aired December 15, 2015.

2 In an interview reported on the blog “OAG Only a Game,” Randle related how he and some teammates helped a victim of cerebral palsy, Davey Finnegan, buy a voice communicator with the song, “Just a Chance, Kingdome.” He said they raised $20,000. https://wbur.org/onlyagame/2015/05/30/lenny-randle-mlb-history-kingdome.

3 Author interview with Lenny Randle, July 29, 2016. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations attributed to Randle come from this interview.

4 Ibid.

5 Elliott “Bump” Wills was the son of Dodgers great Maury Wills.

6 Nettuno is located on the Mediterranean coast of Italy approximately 30 miles south-southeast of Rome. Named after Neptune, god of the sea. It is considered the birthplace of Italian baseball after American soldiers near the end of World War II taught the locals the game. Since 1948, the first year of the Italian Baseball League, Nettuno has been represented by a team in that league. https://centerfieldmaz.com/2010/02/former-met-of-day-lenny-randle-saga.html.

7 Norm Ordaz, interview with Lenny Randle, Clubhouse Chatter, February 28, 2016. https://clubhousechatter.mlblogs.com/2016/04/23/clubhouse-chatter-lenny-randle-2/.

8 Dan Epstein, “Lenny Randle’s Italian Baseball Renaissance,” Rolling Stone, April 16, 2015. rollingstone.com/sports/features/lenny-randles-italian-baseball-renaissance-20150416.

9 https://thesundevils.com/sports/2000/8/16/208252919.aspx.

10 Norm Ordaz.

Full Name

Leonard Shenoff Randle

Born

February 12, 1949 at Long Beach, CA (USA)

Died

December 29, 2024 at Murrieta, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.