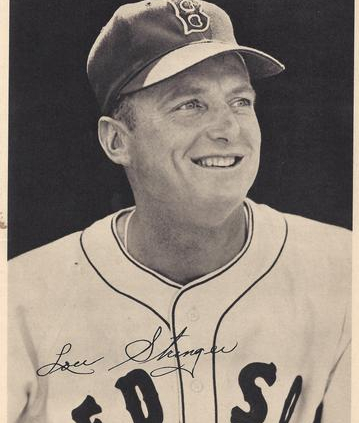

Lou Stringer

A ballplayer turned Hollywood actor and a car dealer who once sold a Corvette to Elvis Presley. Lou Stringer was all three.

A ballplayer turned Hollywood actor and a car dealer who once sold a Corvette to Elvis Presley. Lou Stringer was all three.

Louis Bernard Stringer was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, on May 18, 1917. When Lou was three years old, his father moved the family to East Los Angeles. Robert Stringer had been a wood mechanic, working with buzz saws, band saws, and other equipment that gave him some respiratory problems.1 He developed a bad cough and was forced to retire, but with a large family (seven boys and one girl), others in the family began to pick up work so he didn’t have to. Lou’s mother, Josephine, never worked outside the home.

Most of Lou’s brothers worked as mechanics. One ran an upholstery business. Lou’s brother Al, five years younger, had worked out with the Cubs as early as 1941 but signed as a shortstop in the Yankees system. He played for three or four clubs in the American Association, but never made the majors.

Lou first started playing ball with the St. Bridget’s grade school team in Los Angeles, competed in the local C.Y.O. league, and later attended Washington High School where he played shortstop on the high school team, a contemporary of Jerry Priddy. Six players in his high school club made it all the way to big league baseball: Stringer, Priddy, Cliff Dapper, Al Lyons, Roy Partee, and Eddie Morris. Lou played some semipro ball on city sandlots, often coached by a man named Mike Catron, before signing with the Cubs’ organization. Credited with the signing were Jigger Statz and Pants Rowland, but Lou recalls, “Pants Rowland, he wasn’t no scout. He was the manager for the club.”2

After signing his contract, Lou was told to report to Ponca City, Oklahoma, the Cubs’ affiliate in the Western Association. He played second base for Ponca City, appearing in 138 games both in 1937 and in 1938. He hit .263 the first year, and .286 the second, improving across the board in his power numbers at the same time. Stringer ranked second or third in the league in several offensive categories, and Ponca City won the pennant that year. The 19-year-old was earmarked for a year in Tulsa but got an invite to spring training when another player failed to show. Instead, he played in the Pacific Coast League for the Los Angeles Angels (alongside Statz) for both the 1939 and 1940 seasons. He hit .272 the first year, but cooled off just a bit to .263 the second, playing in 172 games during the 1940 campaign. He more than doubled his Western Association home run totals. However, Edward Burns, writing in the Chicago Tribune, noted, “It’s Stringer’s defensive skill that has the Cub management a-twitter with excitement.”3

During the offseason, Stringer worked hard — one article reported 12 hours a day, seven days a week — at the North American Aviation Company plant.4

In 1941, Stringer had a very successful spring and Cubs manager Jimmy Wilson termed him “the best rookie I ever saw in spring training.”5 Needless to say, Lou made the Cubs, debuting on Opening Day, April 15, 1941. Batting seventh and playing short, Stringer had a 2-for-3 day, with a two-base hit and two runs scored. He also made four errors. The leftfielder was Lou Novikoff, whose career had paralleled Stringer’s, all the way from Ponca City to Los Angeles to Chicago. Both had their Los Angeles contracts purchased by the Cubs on the same day in August 1940 and, training on Catalina Island in 1941, both made the club. There had been a little controversy beforehand. Both Stringer and Novikoff held out — unusual for minor leaguers who’d never had a taste of major league ball — but Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis intervened and the two players more or less capitulated. “It was stupid. We didn’t get anything out of it. I got $5,000 and that was what I got,” Stringer said later.

Stringer had played only second base, but Billy Herman was a fixture at the keystone, so Stringer filled in at shortstop. On May 6, though, Herman was traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers. Stringer had effectively beaten out Herman for the job, but it was the Dodgers who went all the way to the World Series while the Cubs finished 30 games behind. Not surprisingly, though, Stringer very much liked skipper Jimmy Wilson. “I liked Jimmy. He was fine. Good dad, good husband. He was a good manager.”

Playing in 145 games, Stringer hit .246, very good figures for a shortstop in that era. He was the first one of the Chicago Cubs to sign his 1942 contract, signing in October 1941. He played out the 1942 season, getting into 121 games and hitting .236, playing some at second base and some at third. With the war under way, he enlisted as a private in the Army Air Corps. He graduated from Air Force Mechanics School at Williams Field Advance Flying School in Chandler, Arizona in January 1943. “I went in as a mechanic and I come out as a (physical training) instructor,” he recalled. “I handled all the PT for all the cadets who were there. There were three or four hundred cadets there and I had three or four classes every day for them and I headed up their PT. Williams Field, Arizona. That was an air base.” He was sent to the Army’s Physical Training Instructors School at Miami Beach. He graduated in November.

News reports indicate that Stringer did well in the service. A May 1943 story in the Los Angeles Times said that soldiering was his “greatest thrill” and he was named Soldier of the Month at Williams Field.6 At the time of the story, Lou had a .425 average playing for the Williams Field Fliers.

Back from the war, Stringer played second, short, and third for the Cubs in 1946, but got only 209 at-bats, hitting .244. Cubs manager Charlie Grimm “never liked me,” he said. Stringer was released to the Angels in January 1947 and the team won the Pacific Coast League pennant. Lou batted .293, driving in 72 runs. In February 1948, the Cubs sold him for the $10,000 waiver price to the New York Giants, who assigned his contract to the Hollywood Stars, also in the Coast League. The club played just 15 minutes from his house. It was another season he very much enjoyed, this time hitting an even .333 and leading the league with 50 doubles, while driving in 99 runs. At season’s end, he was named both the team’s MVP and the “most popular player.” Manager Jimmy Dykes quit on August 28 and Stringer took over as player-manager. But right after Hollywood finished its season, the Red Sox purchased his contract, and he wasted no time getting to Boston. He’d finished up playing a doubleheader against Sacramento on September 19, took a plane that night, and found himself in a ball game in Detroit the evening of September 20. The Los Angeles Times story said that the Stars manager had been “fired” but he was fired “upward, like a space rocket. The Boston Red Sox bought him to help in their frantic fight for the American League pennant.”7

He got into four games, and only had one hit in 11 times at the plate, but it was a home run. The Sox had another second baseman, named Bobby Doerr, and Stringer found himself in a utility role behind Doerr, Vern Stephens, and Johnny Pesky.

He really liked Pesky: “I got along real good with him. I happened to be Catholic and he was Catholic, and we got along real good. Go to church on Sunday and stuff. Dom DiMaggio, he was Catholic. We had quite a few Catholics on the club.”

In 1949, Stringer stayed with the Sox and got into 35 games, but mostly defensively (he only had 41 at-bats, batting .268 during his limited opportunities.) Back for another full year in 1950, Lou had even less work, just 17 at-bats in 24 games. He hit .294. In his two-plus seasons with Boston, he only drove in nine runs.

During the off-seasons, starting right after the war, Stringer worked in the automobile business, selling cars in the Los Angeles area for Harry Mann Chevrolet. Mann later became, Stringer says, “the world’s largest Corvette dealer.”

The Red Sox let him go and he signed on with Hollywood for 1951, playing a full year and hitting .284. He wasn’t entirely unhappy to be playing near home once more. “It’s great, of course, to be in the majors,” he told Al Wolf of the Los Angeles Times. “That’s the goal of every ballplayer. And coming down again kinda hurts. But I’d rather play every day in the minors — especially here in my home town — than just sit on the bench in the big time. You go nuts doing nothing.”8 He had no gripes about Boston managers Joe McCarthy and Steve O’Neill, recognizing that the talent on those ballclubs was just so deep he wasn’t truly needed. “I just couldn’t seem to get a chance to show what I could do.”9 He also had a sense of humor. At one point, he explained why he never worried about slumps: “I’ve been in a slump all my life.”10 That’s a little self-effacing for a reserve middle infielder of the era with a fine .242 batting average.

After the season, he enjoyed a seven-week tour of Japan with Joe DiMaggio and a number of other players. “We played to over a million people. It was a great, great outing. Joe, Dom, and Vince DiMaggio there in the outfield, and I played third. I think we lost one game, and the only reason we lost that was a couple of the guys got so drunk they couldn’t play.”

He began 1952 with Hollywood, but then moved on to San Diego in May. The combined stats for the year show him hitting a solid .275 with 85 RBIs. The next year began with San Diego, but he moved to San Francisco and became player-manager there. The following four seasons saw Stringer move to a new city, as a player-manager each year. He managed and played for Yakima (1954), Boise (1955), Pocatello (1956), and Des Moines (1957). The final season started with the Des Moines Demons, where he lasted but 47 games. “Charley Grimm. He’s the one that pushed me there. He was the big shot, a manager in the big leagues. He knew somebody there and that’s the reason I went to Des Moines. I didn’t know anybody there at all. I was lost when I went there. And we didn’t win…so I just stopped and left after the middle of the season. I came back to L.A.” A month later, the Hollywood Stars offered him a contract and he played in an even dozen games for Hollywood and San Francisco, but his pro ball career was really done.

Stringer spent a good deal of time appearing in a number of Hollywood films, particularly those with baseball themes such as The Jackie Robinson Story and The Stratton Story. He did a fair amount of acting work but became tired of all the downtime — standing around on movie sets — and went back to selling cars.

“I came back and went back to the automobile business. I was there for years. I made more money there than I ever did in baseball.” Selling the Corvette to Elvis wasn’t a hard sell, Stringer told Steve Buckley. “He called and ordered it over the phone. He wanted me to drive it out to this place he was staying at in Hollywood and drop it off….When we got there, he gave me a check, and that was pretty much it. Turns out he bought the car so he could give it to some girl. He was nice, but I don’t think he said 20 words while I was there.”11

Sounds a little reminiscent of Lou’s teammate Ted Williams. “Ted was a loner. We’d all go out and eat dinner, except Ted. He mostly kept to himself, or he went fishing somewhere.” Lou shared an early Ted Williams memory with Buckley, of a time that he was coming out of the batting cage and passed Williams. “He didn’t know me very well yet, and he said, ‘Hey, you, who’s the best hitter in baseball?’ And I said, ‘You are.” And he said, ‘You’re goddamn right I am’ as he walked away.”

Lou married twice. His first wife, Helen, the mother of his two children, died in 1993. They had one daughter, Linda, and one son, Tom. “My son never played ball. He’s a college graduate. He runs this place we’re living right now.” Stringer lived with his second wife Wilma in a retirement community near San Diego owned by his son and four partners.

On October 19, 2008, he died at Freedom Village at Lake Forest, California. He was survived by Wilma, his daughter Lynda and son Tom, as well as four grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.12

An earlier version of this biography originally appeared in SABR’s “Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948” (Rounder Books, 2008), edited by Bill Nowlin. It also appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Thanks to Tom Stringer for assistance in preparing this biography.

Notes

1 Much of the family information derives from an interview with Lou Stringer done on March 3, 2006 by Bill Nowlin.

2 All direct quotations by Lou Stringer come from the March 3, 2006 interview, unless otherwise noted.

3 Edward Burns, “Cubs Buy Novikoff, Stringer from Angels; Report on ’41,” Chicago Tribune, August 31, 1940: 17.

4 For an article on Stringer prior to induction, see Braven Dyer, “Lou Stringer Slated to Be Drafted Soon,” Los Angeles Times, November 11, 1941: 19.

5 “Wilson Labels Stringer Best Rookie He Ever Saw in Training,” Los Angeles Times, April 1, 1941: A9.

6 “Soldiering Top Thrill, Claims Lou Stringer,” Los Angeles Times, May 28, 1943: A12.

7 Al Wolf, “Lou Stringer ‘Fired’ — Up to Boston Red Sox,” Los Angeles Times, September 20, 1948: C1.

8 Al Wolf, “Stringer Says He Wants Action,” Los Angeles Times, January 26, 1951: C2.

9 Ibid.

10 Harold Kaese, “The Slump _ It Eludes None,” Boston Globe, June 8, 1969: 96.

11 Steve Buckley, Boston Red Sox: Where Have You Gone? (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2005), 72.

12 “Lou Stringer,” obituary, Orange County Register, October 23, 2008.

Full Name

Louis Bernard Stringer

Born

May 13, 1917 at Grand Rapids, MI (USA)

Died

October 19, 2008 at Lake Forest, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.