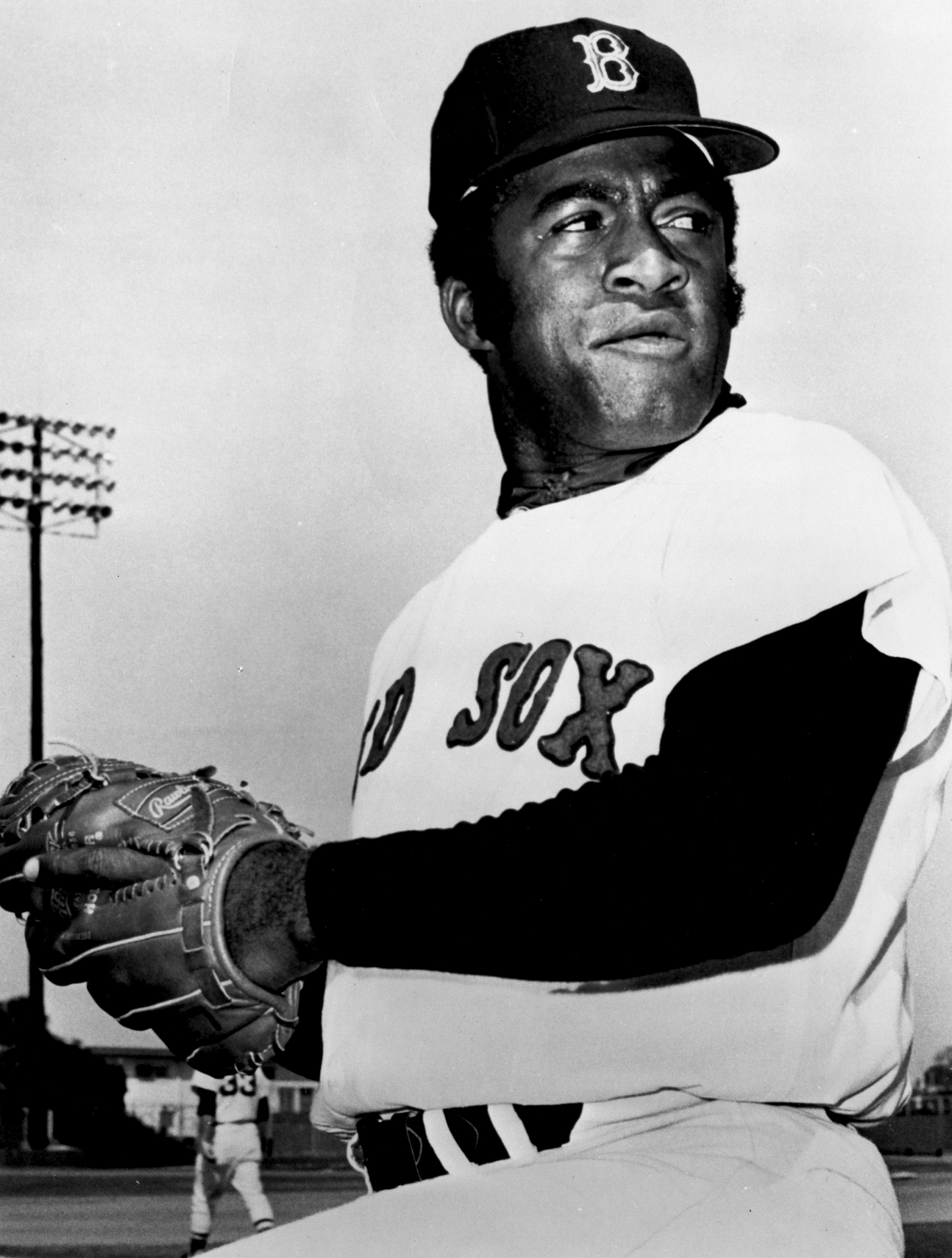

Luis Tiant

Luis Clemente Tiant y Vega, a charismatic right-handed pitcher whom Reggie Jackson called “the Fred Astaire of baseball,” won 229 games over parts of 19 seasons in the major leagues.1 His midcareer comeback, dramatic family reunion, and World Series heroics inspired a region, likely leaving him one of the most beloved men ever to play for the Boston Red Sox.

Luis Clemente Tiant y Vega, a charismatic right-handed pitcher whom Reggie Jackson called “the Fred Astaire of baseball,” won 229 games over parts of 19 seasons in the major leagues.1 His midcareer comeback, dramatic family reunion, and World Series heroics inspired a region, likely leaving him one of the most beloved men ever to play for the Boston Red Sox.

Tiant was born in Marianao, Cuba, the son of Luis and Isabel. His father, Luis Eleuterio Tiant, was a legendary left-handed pitcher who starred in the Cuban Leagues and the American Negro Leagues for 20 years. The elder Tiant was famous for a variety of outstanding pitches (including a screwball, spitball, and knuckleball), a tremendous pickoff move, and an exaggerated pirouette pitching motion. As late as 1947, at the age of 41, Luis put together a 10-0 record for the New York Cubans and pitched in the East-West All-Star Game. Monte Irvin claimed that Luis would have been a “great, great star” had he been able to play in the major leagues.2

The younger Tiant was an only child, and grew up in a baseball-mad country. He was a star on various local youth teams, and as a 16-year-old played on an all-star club that traveled to Mexico City for an international tournament. His father did not encourage him to make a career of the game, believing there was little chance of a black man being successful in baseball, but his mother was more supportive and carried the day.

After failing a tryout with the Havana team of the International League, Luis started his professional career in 1959, at age 18, with the Mexico City Tigers. His first year was quite poor (5-19, 5.92 ERA), but he followed this up with 17 wins in 1960 and 12 more the next year, after being delayed for two months trying to leave his homeland. At the end of the 1961 season, the Cleveland Indians purchased his contract for $35,000.

During these three seasons, Luis spent his summers living in Mexico City, and then returning to Havana for the offseason to play winter ball and be with his family. In 1961 he met Maria del Refugio Navarro, a native of Mexico City, at a ballpark – she was playing for her office softball team. After a short courtship, Luis and Maria married in August 1961. At the close of the season they were planning to return to Luis’s home in Marianao. But the political embarrassment and potential economic hardship of massive Cuban emigration led Fidel Castro’s government to ban all outside travel. Accordingly, upon the advice of his father, Luis did not return home to Cuba in 1961, not knowing when or if he would see his parents again.

Now the property of the Indians, Luis pitched for Charleston in the Eastern League in 1962 and had a respectable year (7-8, 3.63) considering that he was living in an English-speaking country for the first time. In 1963, for Burlington, he was likely the best pitcher in the Carolina League, finishing 14-9, including a no-hitter, with a 2.56 ERA, leading the league in complete games, strikeouts, and shutouts. He was 22 years old, and presumably one of the prizes of the Cleveland farm system.

The following winter Tiant was left off the Indians’ 40-man roster, but no team risked the $12,000 it would have taken to claim him. Despite a good spring in 1964, the Indians first sent him back to Burlington, but an injury to a pitcher on their Triple-A Portland team in the Pacific Coast League brought Tiant to Oregon for the 1964 season. The Portland Beavers staff also included Sam McDowell, one of the more renowned young phenoms in baseball. McDowell was 20 years old, but had spent parts of the last three seasons with the Indians, and was clearly the star of the Portland team at the start of the season. Tiant was not in the rotation.

Luis picked up a relief win in Portland’s first game, and another a week later. His first start was on May 3, in the Beavers’ 15th game. McDowell, meanwhile, started hot and got hotter, pitching a one-hitter and no-hitter in consecutive starts in early May, before finally getting recalled on May 30 when his record had reached 8-0 with a 1.18 ERA, with 102 strikeouts in 76 innings.

Tiant quietly built up his own résumé; at the time of McDowell’s promotion, Luis was 7-0 with a 2.25 ERA. With much lower expectations, Tiant was slower to get the attention of the Indians’ brass. After finally losing 2-0 on June 5, Tiant won four more games to finish June with a 12-1 record. The Indians finally recalled him on July 17. Tiant finished 15-1 (a PCL record .938 winning percentage) with a 2.04 ERA, completing 13 of his 15 starts.

Tiant joined the Indians in New York on Saturday morning, July 18, and was asked by his manager, Birdie Tebbetts, if he was ready to pitch. When advised that he was, Tebbetts told him he was pitching the next day against Whitey Ford. Tiant responded with a four-hit shutout, striking out 11. Luis finished 10-4 for the Tribe with a 2.83 ERA. His total line for 1964: a 25-5 record and 2.42 ERA in 264 innings.

Luis was afflicted with a sore pitching arm in 1965, finishing 11-11, and showed up the next spring having lost 20 pounds on the advice of his father. He started the 1966 season with three consecutive shutouts, a streak that ended in Baltimore when Frank Robinson hit a ball completely out of Memorial Stadium, the only time that was ever done. Luis hit a rough spell in May and June and spent most of the last half of the season in the bullpen, notching eight saves in 30 relief appearances. Despite only 16 starts, his five shutouts topped the American League. His ERAs in 1966 and 1967 were 2.79 and 2.74, respectively, more than adequate, but not enough to win more than 12 games each year.

In 1968 Tiant became a star, finishing 21-9 and posting a league-leading 1.60 ERA. Luis also led the league with nine shutouts, including four in succession (one short of the then-record set by the White Sox’ Doc White in 1904). He pitched his best game on July 3 in Cleveland when he recorded 19 strikeouts in 10 innings against the Twins. In the top of the 10th, the Twins got runners on first and third with no one out but Luis responded by striking out the side. The Indians pushed across a run in the bottom on the 10th to give him a 1-0 victory.

The following week, Luis started and lost the All-Star Game, giving the NL an unearned run in the first inning that turned out to be the only run of the game. After a 3-0 loss to the Tigers on August 14, Denny McLain suggested: “Luis and I would each be fighting for 30 wins if he had our kind of hitting to go with his kind of pitching.”3 (Catcher Bill Freehan took it a step further, insisting that Luis would be “going for 40 wins.”)4 In the event, McLain finished 31-6 with a 1.96 ERA, and won the Cy Young and MVP Awards unanimously. Tiant ended his season with a one-hit, 11-strikeout masterpiece against the Yankees in New York.

The Indians finished 1969 with the worst record in the American League, and their worst winning percentage in 54 years. Luis fell to 9-20, and posted an ERA of 3.71. It was not really as bad as it seemed – changes to the strike zone and mound sent the league ERA up to 3.62. Nonetheless, Luis was an average American League pitcher, which was quite a step down from 1968.

In December of 1969, Tiant was traded to the Minnesota Twins in a six-player deal that brought Dean Chance and Graig Nettles to the Indians. In 1970 he won his first six decisions for a very strong Minnesota team, but left during his sixth victory with a sore shoulder that had been bothering him since the spring. Luis went to see a specialist, who found a crack in a bone in his right shoulder and prescribed only rest. He sat down for just 10 weeks, and returned to lose three of four decisions in the final weeks of the 1970 season.

By spring training of 1971, Tiant claimed to be fully recovered, but soon pulled a muscle in his rib cage, missed two weeks, and was otherwise ineffective in only eight innings. On March 31 the Twins gave him his unconditional release. Calvin Griffith believed that Tiant was finished at age 30. Suitably devastated, Luis believed the move was intended only to save money.

By spring training of 1971, Tiant claimed to be fully recovered, but soon pulled a muscle in his rib cage, missed two weeks, and was otherwise ineffective in only eight innings. On March 31 the Twins gave him his unconditional release. Calvin Griffith believed that Tiant was finished at age 30. Suitably devastated, Luis believed the move was intended only to save money.

The sole team willing to give Tiant a shot was the Atlanta Braves, who signed him to a 30-day trial with their Triple-A Richmond team. After limited work, the Braves were unwilling to promote him at the end of the trial period, so he signed with Louisville, the Red Sox’ Triple-A affiliate. He pitched very well in 31 innings for Louisville – 29 strikeouts and a 2.61 ERA – and was summoned to Boston on June 3.

He was not an immediate success with the Red Sox. After his first appearance, on June 11, resulted in five runs in only one inning, Clif Keane wrote in the Boston Globe: “The latest investment by the Red Sox looked about as sound as taking a bagful of money and throwing it off Pier 4 into the Atlantic.”5 Tiant remained in the rotation, but he dropped his first six decisions as a starter. After one loss, Keane led a game story with, “Enough is enough.”6

Nonetheless, manager Eddie Kasko believed there were signs that Tiant could become a quality pitcher again. He threw seven very good innings against the Yankees but lost 2-1 on a two-run home run by Roy White. He threw 10 shutout innings, and 154 pitches, against the Twins, but did not figure in the decision. Kasko finally took him out of the rotation in early August. He was better in the bullpen, finishing 1-1 with a 1.80 ERA in that role. After his four-month audition, many in the media were surprised that Tiant was still on the 40-man roster in the spring.

On March 22, 1972, the Red Sox traded Sparky Lyle to the Yankees for Danny Cater and Mario Guerrero, a trade that ranks among the worst that the Red Sox ever made, but which likely saved Luis’s spot on the team. Kasko elected to keep him for the team’s bullpen. By the end of July, Kasko’s faith seemed to have been justified, as Luis was effective in a variety of roles – the occasional spot start, a ninth-inning save or a long-relief stint. The team had floundered for the first half of the season, but a July hot streak had pulled them to within five games of first place on August 4.

On August 5 at Fenway Park, Tiant started for just the seventh time and beat the Orioles. One week later, in Baltimore, he beat the O’s again, pitching six no-hit innings before settling for a three-hitter. After a relief appearance, he pitched a two-hitter in Chicago’s Comiskey Park on August 19, losing a no-hitter with two outs in the seventh. After this game Kasko finally announced that Luis was in the rotation to stay.

Surprisingly, the Red Sox had climbed into a fierce four-team pennant race with the Yankees, Orioles, and Tigers. Even more surprisingly, Luis Tiant had become their best player. Over a period of 10 starts, beginning with the game in Chicago, Luis furnished a record of 9-1 with six shutouts and a 0.82 ERA, all nine victories being complete games. He began with four straight shutouts, his streak of 40 scoreless innings ending during a four-hit victory over the Yankees at Fenway Park on September 8. After a loss in Yankee Stadium, Luis blanked the Indians back home on the 16th.

Before the second game of a twi-night doubleheader against the Orioles on September 20, the fans rose to their feet as Luis walked to the bullpen to warm up and gave him such an ovation that his teammates joined in. The crowd spent most of the evening chanting “Loo-Eee, Loo-Eee, Loo-Eee,” as their hero recorded out after out. When he came up to bat in the bottom on the eighth on his way to another shutout, the crowd again rose to give him an ovation that continued throughout his at-bat, the break between innings, and the entire top of the ninth. Larry Claflin, the veteran Boston Herald sportswriter, wrote that he had never heard a sound like it at a game, unless it was “the last time Joe DiMaggio went to bat in Boston.”7 Carl Yastrzemski, who had had one of baseball’s most famous Septembers only five years earlier, said, “I’ve never heard anything like that in my life. But I’ll tell you one thing: Tiant deserved every bit of it.”8

After clutch victories over both the Tigers and Orioles, Tiant lost his final start, on October 3 in Tiger Stadium, a game that clinched the pennant for Detroit on the next to last day of the season. Though he was essentially a relief pitcher for the first four months of the season, Luis finished 15-6 and won his second ERA title (1.91) and the Comeback Player of the Year award. By leading the Red Sox into an unexpected race for the pennant, Tiant won the hearts of the Red Sox fans. He would never lose them.

He capped his comeback by winning 20 for the second time in 1973, while the Red Sox again finished second. The next year Luis won his 20th by August 23 to give his team a seemingly safe seven-game lead. But the Red Sox went into a horrific teamwide batting slump that was responsible for a disastrous fade – they were 8-20 during one stretch – and consigned them to a third-place finish, seven games behind Baltimore. Considered an MVP candidate in August, Tiant won only two of his final seven decisions, although he continued to pitch well. In the four starts after his 20th victory, he lost 3-0, 1-0, and 2-0, and then had a no-decision in a game in which he gave up one run in nine innings. He finished 22-13 for the season with a league-leading seven shutouts.

Tiant was revered by his teammates in Boston, much as he had been in Cleveland and Minnesota. In 1968 Thomas Fitzpatrick wrote an article about Tiant in Sport entitled “The Most Popular Indian.” When the Twins released Tiant, their longtime publicist Tom Mee called the scene in the locker room as Luis said goodbye to his teammates “the most forlorn experience I’ve ever had in baseball.”9

The Red Sox had recently been a fractured team, but Luis kept his teammates laughing, largely by making fun of them and himself. He called Yastrzemski “Polacko” and Fisk “Frankenstein.” After the 1972 season, Red Sox pitcher John Curtis wrote a newspaper story about trying to explain to his wife why he loved Luis Tiant. Dwight Evans would later say, “Unless you’ve played with him, you can’t understand what Luis means to a team.”10

Tiant’s physical appearance was part of his charm. Red Smith once wrote that he looked like “Pancho Villa after a tough week of looting and burning.”11 Boston writer Tim Horgan later suggested that Tiant’s “visage belongs on Mt. Rushmore.”12 A barrel-chested man who looked fatter than he really was, Tiant would often emerge from the shower with a cigar in his mouth, look at his naked body in the mirror and declare himself to be a (in his exaggerated Spanish accent): “good-lookeen sonofabeech.”

Luis struggled for most of the 1975 season. While the Red Sox took over the division lead for good in late June, 34-year-old Tiant was seen more and more as an aging back-of-the-rotation starter. He may have had a reason for his struggles: His heart and mind were occupied with a long-overdue family reunion.

Though his mother had visited Mexico City to visit Luis and his family in 1968 (his father was reportedly jailed, with his release only assured on her return), Luis had not seen his father in 14 years. A renowned jokester, his mood darkened when he thought of his homeland and his parents. In December 1974 he told Boston Herald reporter Joe Fitzgerald: “My father is going to be 70 years old soon, and I don’t know how many years he has left. He’s working down there at a garage, serving gas, and I can’t even send him a dime for a cup of coffee on Christmas.”13 Luis spoke of his parents often, and had been led to believe many times over the years that a reunion could be arranged. When asked about his namesake, Luis would say, “I am nowhere near the pitcher my father was.”

In May 1975 US Sen. George McGovern (D-South Dakota) made an unofficial visit to Cuba to see Fidel Castro. While it was not the reason for his trip, he carried with him a letter from his Senate colleague, Edward Brooke III (R-Massachusetts), making a personal plea that Luis’s parents be allowed to visit their son in Boston. The letter suggested that “Luis’ career as a major league pitcher is in its latter years” and “he is hopeful that his parents will be able to visit him during this current baseball season.”14 The very next day, Castro approved the request and put the diplomatic wheels in motion for a visit.

After several delays and postponements, Isabel and the elder Luis touched down in Boston’s Logan Airport on August 21. Their son, with his wife, Maria, his three children, and dozens of reporters and cameramen, greeted them. As witnessed in homes all over New England, Luis embraced his father and shamelessly wept. Isabel told her son, “I’m so happy I don’t care if I die now.”15

On August 26 the Red Sox arranged for Luis’s parents to be introduced to the crowd and for his father to throw out a ceremonial first pitch. After a prolonged ovation, the 69-year-old Tiant, standing on the Fenway Park mound adorned in a brown suit and Red Sox cap, took off his coat and handed it to his son. He went into his full windup and fired a fastball to catcher Tim Blackwell – alas, low and away. Looking vaguely annoyed, he asked for the ball back. Once more he used his full windup, and floated a knuckleball across the heart of the plate. The fans roared as he left the field. His son later commented, “He told me he was ready to go four or five innings anytime.”16

The younger Tiant was hit hard that night and again four days later. The whispers in the press box included the lament that it was a shame that his parents had not gotten here a year earlier, when Luis was still an effective pitcher. At this point, Luis (with a record of 15-13 and an ERA of 4.36) took 10 days off to rest his aching back.

On September 11 manager Darrell Johnson decided to give Luis one last chance to get it going, against the Tigers. The Red Sox lead, once as high as nine games, was now five. Luis responded with 7⅔ innings of no-hit ball before allowing a run and three hits. When asked about the hit by Aurelio Rodriguez that ruined the no-hitter, Luis’s father responded, “Don’t talk about a lucky hit. The man hit the ball pretty good.”17

Luis’s next start, on September 16, was the biggest game of the year and one of the legendary games in the history of Fenway Park. The hard charging Orioles, now 4½ games out, were in town and Jim Palmer faced Tiant. Many observers claim that there were well over 40,000 people in the park that night, several thousand over its official capacity. Predictably, Tiant pitched his first shutout of the year, a 2-0 five-hitter, and the crowd chanted all evening (“Loo-Eee, Loo-Eee, Loo-Eee”). Later in the month Tiant pitched another shutout against Cleveland, and the Red Sox won the pennant by 4½ games.

After these three remarkable performances, Tiant was the obvious choice to start the first game of the divisional playoffs. He three-hit the Athletics to spark a Red Sox sweep. One week later he began the 1975 World Series with a five-hit shutout of the Cincinnati Reds. In Game Four, in perhaps the quintessential performance of his career, Luis threw 163 pitches, worked out of jams in nearly every inning, and recorded a complete-game 5-4 win. He could not hold a 3-0 lead in Game Six, and was finally removed trailing 6-3 before Bernie Carbo and Carlton Fisk bailed him out with legendary home runs. Alas, the Red Sox lost the seventh game to the Reds the next evening.

The 1975 postseason marked the zenith of Tiant’s career, as his family story, his charm and charisma, his unique pitching style, and, finally, his talent made him a national star. At age 34, he was said to have thrown six pitches (fastball, curve, slider, slow curve, palm ball, and knuckleball) – from three different release points (over the top, three-quarters, and side-arm). His windup and motion seemed to vary on a whim. Roger Angell, writing in The New Yorker, once tried to put a name to each of his motions, including “Call the Osteopath,” “Out of the Woodshed,” and “The Runaway Taxi.”18 It was said that over the course of the game Luis’s deliveries allowed him to look each patron in the eye at least once.

With all of his loved ones nearby, Tiant won 21 games for a struggling Red Sox team in 1976. His parents never returned to Havana. They stayed with Luis for 15 months, until his father died of a long illness in December 1976. Two days later, while resting for the next day’s memorial service, Luis’ mother, Isabel, died in her chair, although she had not been ill. The two were buried together near Luis’s home in Milton, Massachusetts.

After watching several of his teammates reap the rewards of the new free-agency era, Luis had a protracted holdout in the spring of 1977. He came to terms, but managed only 12 and 13 wins the next two years. Tiant’s relationship with the team’s management was strained from this point forward.

After their stunning slump late in the 1978 season, the Red Sox had crawled back to within two games of the Yankees with eight remaining. Prior to the subsequent contest in Toronto, Luis said, “If we lose today, it will be over my dead body. They’ll have to leave me face down on the mound.”19 He won, and the Red Sox went on to win their last eight games, including two more victories from Tiant on three days’ rest. On the final day of the season, the Red Sox needed a win and a Yankee loss to force a playoff game. Catfish Hunter and the Yankees lost in Cleveland and Tiant dazzled the Fenway crowd yet again with a two-hitter against the Blue Jays.

In the offseason, the Red Sox offered the 38-year-old Tiant only a one-year contract, allowing Luis to sign with the New York Yankees for two years, plus a 10-year deal as a scout. Dwight Evans was devastated at management’s ignorance of what Luis meant to the team. Carl Yastrzemski says he cried when he heard the news: “They tore out our heart and soul.”20 Heart and soul aside, Tiant’s September-October record for the Red Sox was 31-12. The Red Sox would not be in another pennant race for several years.

Luis won 13 games in 1979, including a 3-2 victory over the Red Sox in September, before falling to 8-9 in 1980. After the season, the Yankees let him go. He signed with Pittsburgh in 1981, but spent most of the season with his old team in Portland. He excelled again for the Beavers – 13-7, 3.82, including a no-hitter – but struggled with the Pirates and was released at the end of the season. He finished up his major-league career with six games for the 1982 Angels, with his final win coming against the Red Sox on August 17.

Tiant spent several years scouting for the Yankees in Mexico, always dreaming of a job with a major-league team. He coached in the minor leagues for the Dodgers and White Sox in the 1990s before becoming head baseball coach for the Savannah (Georgia) College of Art and Design. He held the job for four years. For several years in the new century, Tiant worked as a minor-league pitching coach and Spanish language broadcaster for the Red Sox. In 1997 he was inducted into the Red Sox Hall of Fame, and he remains a presence around the club.

In 2007 Tiant returned to Cuba to visit friends and family, a story told in the documentary film The Lost Son of Havana, which premiered in 2009.

Luis and Maria have raised three children: Luis Jr. (born in 1961), Isabel (1968), and Daniel (1974).

Luis Tiant was one of the most respected and revered players of his time, with his teammates, opponents, the media, and his fans. His career was one of streaks, but his best streaks – in the pennant races of 1972, 1975, and 1978, and in the 1975 postseason – occurred when his team needed him most. He was believed to be finished in the middle of his career but came back to have most of his best seasons and to become, for a few weeks in 1975, the center of the baseball world.

Postscript

Tiant died at the age of 83 on October 8, 2024.

Notes

1 Roger Angell, “Agincourt and After,” in Five Seasons (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1977), 292.

2 Luis Tiant and Joe Fitzgerald, El Tiante – The Luis Tiant Story (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1976), 7.

3 Tiant and Fitzgerald, El Tiante, 67-68.

4 Tiant and Fitzgerald, El Tiante, 68.

5 Tiant and Fitzgerald, El Tiante, 113.

6 Peter Gammons, Beyond the Sixth Game (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1985), 169.

7 Larry Claflin, “Red Sox Fans Cheer Tiant,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1972.

8 Claflin, “Red Sox Fans Cheer Tiant.”

9 Tiant and Fitzgerald, El Tiante, 99.

10 Gammons, Beyond the Sixth Game, 163.

11 Red Smith, “Hard Life of Charlie Finley,” New York Times, October 5, 1975.

12 Tim Horgan, “El Tiante – Pitcher, Philosopher,” Boston Herald, February 23, 1985.

13 Tiant and Fitzgerald, El Tiante, 180-181.

14 Tiant and Fitzgerald, El Tiante, 185-186.

15 Tiant and Fitzgerald, El Tiante, 196.

16 Tiant and Fitzgerald, El Tiante, 198.

17 Tiant and Fitzgerald, El Tiante, 203.

18 Angell, “Agincourt and After,” 295-296.

19 Gammons, Beyond the Sixth Game, 149.

20 Gammons, Beyond the Sixth Game, 163.

Full Name

Luis Clemente Tiant Vega

Born

November 23, 1940 at Marianao, La Habana (Cuba)

Died

October 8, 2024 at Wells, ME (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.