Mike Gonzalez

Miguel González enjoyed a long and prolific career as a major-league catcher and coach, and along with Adolfo Luque is considered to be one of the two true patriarchs of baseball in Cuba, where he was a player, manager, and owner in the Cuban League from 1910 through 1960. He was a coach on the 1934 world champion St. Louis Cardinals, and although it was only on an interim basis, in 1938 he became the first Latin American to manage in the major leagues. He was the third-base coach who, depending on your point of view, either waved home or tried in vain to stop Enos Slaughter when the latter made his celebrated “mad dash” from first base on a double by Harry Walker to score the deciding run in Game Seven of the 1946 World Series. Despite these accomplishments and the recognition that came with them, González is probably best remembered for coining one of the most famous phrases in the lexicon of baseball while on a scouting expedition for John McGraw and the New York Giants.

Miguel González enjoyed a long and prolific career as a major-league catcher and coach, and along with Adolfo Luque is considered to be one of the two true patriarchs of baseball in Cuba, where he was a player, manager, and owner in the Cuban League from 1910 through 1960. He was a coach on the 1934 world champion St. Louis Cardinals, and although it was only on an interim basis, in 1938 he became the first Latin American to manage in the major leagues. He was the third-base coach who, depending on your point of view, either waved home or tried in vain to stop Enos Slaughter when the latter made his celebrated “mad dash” from first base on a double by Harry Walker to score the deciding run in Game Seven of the 1946 World Series. Despite these accomplishments and the recognition that came with them, González is probably best remembered for coining one of the most famous phrases in the lexicon of baseball while on a scouting expedition for John McGraw and the New York Giants.

Miguel Angel González Cordero was born on September 24, 1890, in the town of Regla, across the bay from Havana. Not much is known about his early life, other than that he and his family lived humbly in modest surroundings. Baseball had become enormously popular on the island by the time Miguel was a boy, as Cubans began to disavow any ties to Spanish colonialism, including its sports, while looking to the US for inspiration. Like many young Cuban boys at the time, Miguel and his friends learned the game on the fields and lots of the city, using whatever makeshift equipment they could find.

Miguel quickly grew to a height of 6-feet-1 but was extremely gaunt for his size. It was said that he resembled a long loaf of thin Cuban bread, and his physique, along with his childhood occupation delivering bread to his neighbors in Regla, earned him the nickname Pan de Flauta, after a loaf of bread so narrow as to resemble a pan flute. González had played baseball during his school years at the Institute of Havana, and he was working as a bank clerk when he was recruited by Fé, the baseball club that had originated decades earlier in the Havana neighborhood of Jesús del Monte. He made his first appearance for Fé as a shortstop in the professional Cuban League in 1910, appearing in six games and amassing 21 at-bats.

González was catching in Cuba during the following winter when he was noticed by Georges Henriquez, a physician who had purchased the Long Branch, New Jersey, club in the fledging Class D New York-New Jersey League, along with his brothers Carlos and Richard. The three brothers had emigrated from Colombia to the United States with their parents, settling in Manhattan, but evidence suggests they spent time in Cuba as well and were familiar with the brand of baseball played on the island.

They decided to stock the Long Branch club with Cuban players. In addition to González, the brothers lured Cuban stars like Adolfo Luque (at that time Gonzalez’s batterymate), Angel Aragón, Manuel Cueto, Luis Padrón, Tomás Romañach, and Juan Violá; the team was aptly named the Cubans. Richard Henriquez, who had played baseball at Columbia while attending medical school, joined the team himself. Long Branch quickly outclassed its opposition, winning the 1912 pennant by approximately 20 games. While Luque was undoubtedly the star attraction, González hit for an average of .333 and was behind the plate for every game.

After the summer of 1912 the Henriquez brothers sold González’s contract to the Boston Braves, and he made his major-league debut on September 28, appearing in one game and walking once in three plate appearances. He was on the roster of the Braves to begin 1913, but manager George Stallings sent him down to Buffalo, which passed González along to Class B Wilkes-Barre. González refused the assignment and the Long Branch club purchased his optional release from Boston. The Braves recalled González briefly in the fall of 1913, but Long Branch subsequently purchased his outright release.

When González returned to Cuba he was traded from Fé to Habana for the 1913-14 season, which began his affiliation with the Rojos or, as they came to be known later, the Leones, a connection that lasted until the demise of the Cuban League.

At the same time, a letter from William H. Peal, secretary of the Eastern League, to Louis Heilbroner of the Baseball Statistical and Information Bureau described González as a very good hitter who is “catching great ball” in Cuba against American squads, at least one of which, the Birmingham Barons of the Southern Association, had made an offer for his services.1 Heilbroner forwarded the letter to Garry Herrmann, president of the Cincinnati Reds, who signed González for the 1914 season.

In the fall of 1914, González, 24 years old, was named manager of Habana by new owner Abel Linares, who apparently had already taken note of the reserved, studious, and loyal nature of his protégé. González rewarded Linares with a championship in the 1914-15 season, the first of 13 Cuban League titles he would win as manager of Habana.

Meanwhile, González had appeared in 95 games for Cincinnati in 1914, catching in 83 of them and batting.233. Tommy Clarke was established as the regular backstop in Cincinnati, but in early April of 1915 the Reds traded González to the Cardinals for catcher Ivey Wingo. The Cardinals were looking to free up playing time for young catching prospect Frank “Pancho” Snyder. González played the next four seasons with the Cardinals, beginning as a backup for Snyder, who was one of the best catchers in the National League in 1915 at the age of 21, while occasionally filling in at first base.

Despite his size, González had a reputation as a stellar defensive catcher who possessed a strong, whip-like throwing arm, very quick feet, and soft hands for blocking pitches. Snyder himself was considered to be an excellent defensive catcher, one of the best of his era, yet manager Miller Huggins began to use González as his starting catcher as early as 1916, penciling him in as the starter in 84 games compared with 69 for Snyder. J.J. Ward of Baseball Magazine observed, “There are a few better catchers in big league ball than Miguel A. González, but they are very, very few indeed.”2

González batted .262 in 1917. His best season with the bat came in 1918, when he hit .252 with 39 walks and 20 extra-base hits. He stole 14 bases. Despite his success, González was placed on waivers by the Cardinals in May 1919, and was selected by the New York Giants. Manager John McGraw had spent much time in Cuba and had seen González play there in winter ball. On one occasion after Gonzalez’s arrival, McGraw gave his team a pep talk convincing them of victory in the 1919 season, and looked to González, the newcomer, for validation. “We won’t win, Cincinnati has the best team,” replied González, who turned out to be quite prescient on the matter, even if his characteristic candor did not sit well with McGraw.3

McGraw kept González on his roster for four seasons, but Mike’s playing time diminished as the Giants used first Lew McCarty as well as Frank Snyder, whom they had brought on board in 1919, as their starters. González spent considerable time as a bullpen catcher, and McGraw often sought his input on the relative merits of the pitching staff. But by 1922, at age 31, Gonzalez was considered through as a hitter, and the Giants sold his contract to the St. Paul Saints of the American Association.

González had two good seasons with the Saints, batting .298 and .303, and his contract was purchased in the spring of 1924 by the Cincinnati Reds. The Reds subsequently sold him to Brooklyn and González spent spring training with the Robins in Clearwater. The day before the season began, Brooklyn traded González to the Cardinals for infielder Milt Stock.

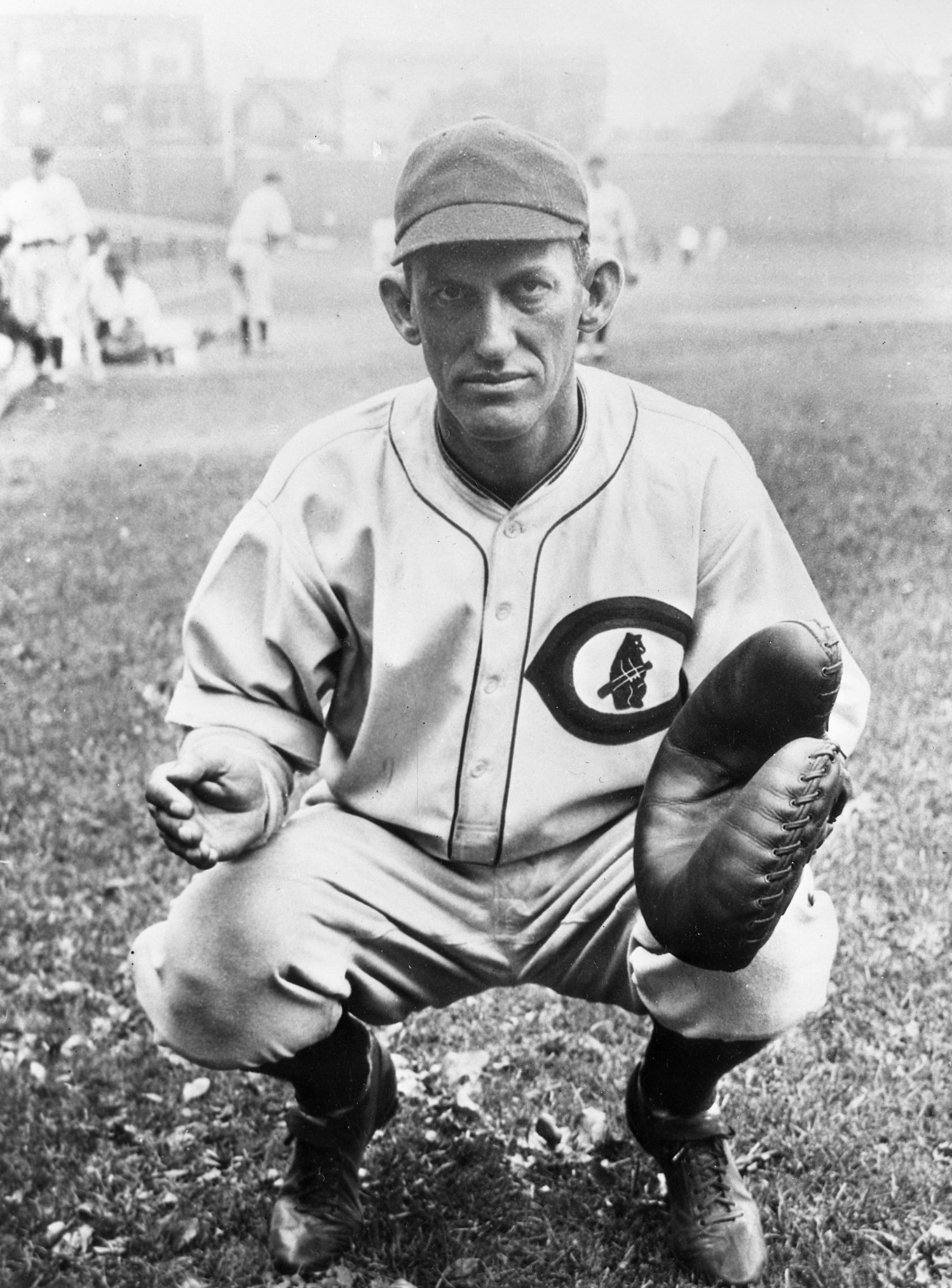

González had a good season with the Cardinals in 1924, playing in 120 games and batting .296, but in May 1925 he was traded to the Chicago Cubs along with infielder Howard Freigau for catcher Bob O’Farrell, who at the time was considered to be one of the finest defensive catchers in the league. González arrived in Chicago only to find young sensation Gabby Hartnett firmly entrenched as the starting catcher for the Cubs; he served primarily as Hartnett’s backup for the better part of the next two seasons.

When Joe McCarthy took over as manager of the Cubs in 1926, he created some controversy by increasing Gonzalez’s playing time at Hartnett’s expense. “There aren’t many players who can’t outhit González, and maybe he doesn’t spiel our language so well, but somehow he makes those pitchers understand him and they’ll learn about pitching to hitters from him,” McCarthy said.4 Of course, Hartnett eventually blossomed into a star, and González did not appear in more than 60 games in any of the next three seasons for the Cubs, although he was a member of the pennant-winning squad of 1929 and appeared twice in the 1929 World Series, won by the Philadelphia Athletics in five games, striking out as a pinch-hitter in Game Two in his lone at-bat.

Undeniably, González’s career in the big leagues represented only half of his baseball life – the rest was spent in Havana. The Cuban League arranged its schedule around that of American baseball, allowing González and many other Cuban players to have dual careers. In the winter they played against fellow Cubans, the finest players from the Negro Leagues, and American major leaguers. The competition was fierce, and the level of play superb. Many major-league teams and mixed barnstorming squads visited the island each winter to play the local teams, only to be startled by the quality of play of Cuban stars like Jose “The Black Diamond” Mendez, Cristobal Torriente, Alejandro Oms, and Dolf Luque. Many of their legendary feats have lived on, such as Mendez’s streak of 25 scoreless innings for Almendares against Cincinnati in a series at Almendares Park in 1908.

Professional baseball in Cuba existed as far back as 1878, but the Cuban League never represented a cross-section of the population on the island – it was centered in Havana, and for all intents and purposes, it really existed as a mechanism for perpetuating one of the greatest and most intense rivalries in the history of the sport, the battle between the Habana Leones, or the Reds, and the Almendares Alacranes, the Blues. Attempts to add clubs from the provinces over the years generally met with failure; one of the steadier teams, Cienfuegos, rarely bothered to schedule games in its own city, traveling to Havana for “home” games in search of a bigger gate.

The first glory years of the Cuban League are generally considered to have taken place between World War I and the onset of the Great Depression, and it was during this period that the two great patriarchs of the sport in Cuba, González and Luque, became the faces of the two “eternal rivals.” While the league shuttled third and fourth teams in and out over a period of years, the one constant was the competition between the Reds and the Blues, between González and Luque, which literally divided the city in two.

By the time this period ended, in 1929, González had managed Habana to six championships, in the seasons of 1918-19 (notable for the participation of the Cuban Stars, a team of Cubans who played in the American Negro Leagues), 1920-21, 1921-22 (an abbreviated season of nine scheduled games, of which only five were completed), 1926-27, 1927-28, and 1928-29, while still serving as a full-time player.

His only notable absence from the league during this period was in the 1923-24 season, won by the Santa Clara Leopardas, considered by many to be the best team ever assembled in Cuba, with an outfield of Oscar Charleston, Pablo “Champion” Mesa, and Alejandro Ohms. González left Habana to form a league of his own in Matanzas, which would feature all Cuban players, and he was replaced at the helm of Habana by his rival, Luque.

There were many reasons for his defection. González was becoming increasingly disaffected with the control promoter Abel Linares exerted over the league. Linares owned all three teams – Habana, Almendares, and Santa Clara – that participated in the 1923-24 season. Also, more American players were traveling to Cuba for the winter campaign, and Gonzalez’s gesture of creating an all-Cuban insurgent league was seen as a protest against this development. Finally, and most significantly, González may have been trying to avert the gaze of Major League Baseball. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, aware that the veneer of invincibility enjoyed by the major leagues was being peeled back by losses to Latin teams, had banned barnstorming in the offseason, which could easily have been construed to include the Cuban League.

When the Roaring Twenties gave way to the Depression, the golden age of the Cuban League ended, and by this time González’s major-league career seemed over as well. The Cubs released him after the 1929 season, saying he had lost his arm strength. González denied it. “I am sorry to leave the Cubs for I have many friends in Chicago, but I have changed teams so many times that one more will make no difference,” he said. “I am through as a Cub, but not as a ballplayer. My arm is all right, although I will have to admit that it is not what it used to be. Someone has said that the Cubs let me go because it went back on me, but that is very funny, because I never noticed it.”5

Unable to find a major-league job, he played for the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association, at age 39. He hit.263 in 92 games and led the league’s backstops with a .993 fielding percentage.

González’s performance caught the attention of Branch Rickey, the general manager of the Cardinals, who signed him for the 1931 season. González played for the Cardinals in 1931 and 1932, but had only 33 plate appearances over the two seasons, serving mostly as a bullpen coach. He did make a significant contribution to the Cardinals’ world championship team in 1931. During the deciding Game Seven against the Athletics, Gonzalez walked from the bullpen to the dugout under the guise of getting a drink of water. What he had in mind was getting a good look in the eyes of starting pitcher Burleigh Grimes, who appeared to be struggling to hold a 4-0 lead late in the game. González hastened back to the bullpen and instructed left-hander Bill Hallahan to start warming up. “Burleigh, she tired,” González said.6 As it turned out, Grimes was indeed tired, and needed Hallahan to enter in the ninth inning with two outs, two runs in, and Philadelphia runners on first and second. Hallahan retired Max Bishop on a fly ball and the Cardinals held on for a 4-2 victory.

After the 1932 season González’s major-league playing career came to an end. He was 41 years old. He finished with a lifetime batting average of .253, but his value was mainly on defense, where he compiled a fielding percentage of .980 and threw out 47 percent of baserunners attempting to steal. He finished within the top three in the National League in caught-stealing percentage five times. In assists as a catcher, he ranks immediately behind Hall of Famers Johnny Bench, Ernie Lombardi, and Mickey Cochrane, and just ahead of Yogi Berra.

For1933 Rickey sent González to the Double-A Columbus Red Birds as a player-coach. González was credited with assisting in the development of the Red Birds’ top pitching prospects, including Paul Dean and Bill Lee. He also managed, at 42, to accumulate 111 at-bats as a backup catcher, with a batting average of .324.

When Cardinals player-manager Frankie Frisch needed a coach for the 1934 team, he did not hesitate to select González, calling him “a great guy, loyal and true.”7 The Gas House Gang won 95 games and the National League pennant, then defeated the Detroit Tigers in seven games in the World Series.

González coached for Frisch and the Cardinals into the 1938 season as the Cardinals’ fortunes faded under the Fordham Flash; they dropped from 96 wins in 1935 to 71 in 1938. Frisch was fired with 16 games remaining in 1938, and González was named interim manager, the first Latin American to manage in the big leagues. This was a bittersweet moment for González, for his promotion came at the expense of his mentor and close friend. “I hate to see him go. He’s a real pal and a good man. I didn’t want him to leave,” he said.8

In the offseason, Rickey and owner Sam Breadon sought out González for his advice on a new manager for the Cardinals, and followed his recommendation that they hire Ray Blades, his tutor at Columbus. González returned to his role as coach under Blades until June 1940, when he briefly took over the reins as manager again after Blades was fired and before Billy Southworth succeeded him. González’s final record as a major-league manager was 9-13.

In Cuba, 1930 was a precursor of an extremely difficult decade for the Cuban League. A contract dispute between the teams and the owners of La Tropical Stadium in Havana reduced the schedule to a mere five games. Over the next three years, the political stability in the country deteriorated as labor strikes and other, more violent measures were taken against the ruthless, heavy-handed government of President Gerardo Machado, who was finally forced out of office in 1933. The playoffs to settle a tie in the 1932-33 season were canceled, and then the entire 1933-34 season was wiped out. The 1934-35 campaign was notoriously weak, with all three professional teams going down to defeat at the hands of the amateur Rum Havana Club.

An improvement in the Cuban economy in the mid- to late 1930s, as well as the exploits of some of the great Cuban players of the era, among them as Martin Dihigo, Raymond “Jabao” Brown, and Lazaro Salazar, led to a revival of interest in the Cuban League. González, who had taken a two-year hiatus, returned for the 1938-39 campaign, but despite a pitching staff that included Dihigo, Tomás de la Cruz, Negro League great Ted “Double Duty” Radcliffe, and Luis Tiant the elder, Habana could finish no higher than second place, five games behind Santa Clara.

The revitalization of the league was also due to a rebirth of the rivalry between Habana and Almendares that began in the following season. Beginning with the 1939-40 campaign, the championship was won by either Habana or Almendares for five consecutive seasons, before Cienfuegos dethroned them in the 1945-46 season, the last to be played at La Tropical Stadium.

González had owned a tobacco and cigar business in Cuba, and was always a level-headed businessman and a good steward of his finances. When the widow of Abel Linares was ready to sell both the Almendares and Habana franchises, González put together a group of investors, and bought the Habana team for $25,000 in 1946. By 1947 he owned the team outright, and a decade later it was appraised at $500,000. But his rise to ownership directly resulted in the end of his career in American baseball.

González had continued coaching under Southworth in 1941, and the Cardinals improved to finish second behind the Brooklyn Dodgers. Beginning in 1942, the Cardinals entered the most hallowed era in their history, winning 106, 105, and 105 games in their next three seasons. In 1942 they edged out Leo Durocher’s Brooklyn team to win the pennant by two games, and went on to defeat the New York Yankees in five games in the World Series. They won the pennant again in 1943 but lost to the Yankees in the World Series. The Cardinals won the Series in 1944, defeating their city rivals, the St. Louis Browns, in six games.

After leading the Cardinals to a second-place finish in 1945, Southworth signed a lucrative contract to manage the Boston Braves, and the Cardinals hired Eddie Dyer as manager. In a testament to how well González was regarded within the organization, and by owner Sam Breadon himself, he was retained and made the third-base coach, at which position he would be involved in one of the most famous plays in World Series history.

With both the Series and Game Seven knotted at 3-3, Enos Slaughter was on first base with two outs in the bottom of the eighth inning. On a 2-and-1 pitch to Harry Walker, Slaughter broke for second. Walker lined a double to left-center field, where Leon Culberson, who had just replaced the injured Dom DiMaggio, raced to his right to field it and throw to the cutoff man, shortstop Johnny Pesky. Slaughter had kept on going around third and beat the startled Pesky’s throw to the plate to score the go-ahead run. The Cardinals held on and won their third World Series in five years.

The winning play was surrounded by some confusion that has caused continuing dispute. Walker’s hit was called a single by some members of the media, which magnified Slaughter’s achievement. Also, DiMaggio, standing on the dugout steps, had yelled to Culberson to move to his right prior to the pitch, but the crowd noise drowned him out, and Culberson did not notice. Pesky, stunned to see Slaughter heading for home, was said to have hesitated upon catching Culberson’s throw, allowing Slaughter to score. The available film of the play shows that Pesky wheeled and threw home without much more than a momentary hesitation. Unfortunately for the Red Sox, his throw was well up the third-base line, allowing Slaughter to score.

Another dispute is whether González put up the stop sign or waved Slaughter home. The video is inconclusive on this matter. The video shows González coming into vision as Slaughter approached third base with his head down, and the only clearly discernible movement the coach made was to backpedal rapidly, almost as if to get out of Slaughter’s way. Slaughter himself was ambivalent on the subject, siding with each point of view on different occasions. Perhaps his most telling comment on the play took place during a television interview in 2000, when he said, “I never saw Mike González, the third-base coach. Whether he tried to stop me or not, I don’t know. I never looked up.”9

For his part, González was persistent in his account of the play, insisting that with two outs and the bottom of the order coming up, he did not hesitate to wave Slaughter around third. If so, he may have been influenced by a play in the fourth inning of Game One, when Slaughter tripled to left-center field with two outs, but was left stranded, with the Cardinals losing the game in extra innings. On this occasion, Pesky fumbled the relay from DiMaggio, but González held Slaughter at third base when he clearly could have scored. González was criticized by some observers of that play for being out of position to make the proper call.

Game Seven marked the end of Miguel González’s career in the major leagues. In many ways his departure was symbolic of the conflict that had arisen between the owners of Organized Baseball in the United States and the independent interests of league owners outside of their purview.

The Mexican League, which had come into existence in the 1930s, had always depended for its success on the participation of many of the greatest Latin American players, including Cubans, as well as the finest African-American players from the Negro Leagues. The president and kingpin was Jorge Pasqual, a multimillionaire who was eager to expand the influence and importance of his league in Mexico’s postwar economic boom. The return from World War II of many gifted baseball players was flooding the available talent pool, and Pasqual wanted his share of the overflow. He offered exorbitant bonuses and salaries to American major leaguers in an effort to get them to jump their contracts and join his league. When his plan began to bear fruit, Commissioner Happy Chandler and the team owners were quick to take action to defend their interests.

Chandler proclaimed that any player who jumped to Mexico, as well as those who played against them in winter leagues, would be blacklisted from Organized Baseball. This was a direct blow to the Cuban League, which had for years drawn on talent from the Mexican League, including famous jumpers like Sal Maglie, Max Lanier, and Lou Klein. The two leagues had formed a summer/winter combination that was attractive to many African-American and Latin players. Many of the top Cuban players, like Dihigo, Luque, and Salazar, had played and managed in Mexico – the baseball connection between the two countries was close. Regardless, Major League Baseball was now in effect restricting Cuban players from playing in their own country.

González and Luque, as well as at least 18 other Cubans, were formally banned from Organized Baseball. On October 17, 1946, González, with eyes on purchasing the Habana franchise, resigned as a coach of the Cardinals. Owner Sam Breadon expressed disappointment, saying, “We’d like to see him come back at any time, and hope he will.”10

As the controversy swirled throughout Cuba, “the eternal rivals” engaged in a pennant race in February 1947 that enthralled the entire nation. The 1946-47 Cuban League season was moved to the new Gran Stadium. The ballpark accommodated 35,000 fans and was centrally located in Havana, which was enjoying an outbreak of postwar tourism that had bolstered the economy. González’s Leones had built a large early lead in the standings, but a tremendous late run by Luque’s Alacranes that saw them win 12 of 13 games at one point, left the outcome hanging in the balance on the last day of the season. Finally, Max Lanier defeated Habana to reward Almendares with the pennant.

With the threat of further sanctions very much in mind, the executives of the Cuban League decided to seek peace. An agreement between Organized Baseball and the Cuban League in the summer of 1947 ended Cuban autonomy over its own professional baseball. The jumpers would be banned, and from then on the major leagues would have control over the flow of players between the United States and Cuba. The Cuban League would in essence become a training ground, a minor league, for developing major league players.

González continued to manage the Leones under the agreement, winning three consecutive championships, in 1950-51, 1951-52, and 1952-53. In the winter of 1953, he made the surprising announcement that he would retire as manager of Habana at the end of the season, but would remain as owner. He retired with many Cuban League managerial records that would never be eclipsed, including most games (1,525), most seasons (34), most wins (917), and most pennants (14). He was elected to the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame in 1955. Habana never won another Cuban League title.

There are many stories about González, some certainly apocryphal and others existing in various forms. Many center on his inability to speak English well; in the perhaps unwitting racism that was commonplace at the time, most sportswriters painstakingly spelled out every word González spoke phonetically, as a rather cruel way of pointing out his problems with the language.

However, González did have a few characteristic mannerisms as well as phrases that he used throughout his baseball career, almost as calling cards. Like many Spanish speakers first learning to speak English, he had trouble with pronouns, often referring to males as “she.” His stock phrase for a person of superior intelligence or intuitive wisdom was a “smart dummy,” while a person who lacked those qualities was a “humpy-dumpy.”11

Gonzalez’s problems with the language did lead to some challenges for his teammates. One of the most famous tales involved a play in a game against the Giants at the Polo Grounds on September 13, 1936. The Cardinals were batting in the third inning of the first game of a doubleheader before a crowd of 64,417, a record National League one-game attendance at the time. With pitcher Henry “Cotton” Pippen on second base and Terry Moore on first, Art Garibaldi hit a line drive into right-center field. Pippen took off but quickly stopped between second and third, unable to understand the instructions of his third-base coach, González. Moore had by then rounded second only to find Pippen directly in his path. The Giants tagged both Pippen and Moore out while Garibaldi, despite having ostensibly doubled, was back on first base. After the inning, an angry González stormed into the dugout. “They no understand, Frank,” he told manager Frisch. “I tell Pippen go and she stop. I tell Moore stop and she go ahead. What do you do with dummies like them? I do my best, Frank, I cannot do some more.”12

Of course, González’s issues with the language resulted in his coining one of the most famous phrases in baseball. After the 1921 season, Giants manager John McGraw told González to scout a young prospect in Cuba over the winter. González, never one for verbosity, replied with a four-word telegram. It read simply, “Good field, no hit,” a phrase that has lived on in the scouting community ever since.

Despite these humorous anecdotes, Gonzalez was never considered to be anything less than an astute baseball man and evaluator of talent. He was renowned among his teammates for his ability to unravel the most complicated signs of the opposing team. In particular, he was excellent at cracking the code that opposing infielders used to signal the forthcoming pitch, and discreetly informed the batter from the third-base coaching box. He had a remarkable memory that allowed him to recall the strengths and weaknesses of every player, both at bat and in the field, and he could recite batting averages at the drop of a hat.

While at first the Cuban League showed signs of surviving the revolution of 1959 that brought Fidel Castro to power, by 1961 professional baseball had been banned in Cuba. It was later reported that some of González’s property was confiscated, but due to his stature and fame, he was allowed to reside in his principal residence, a marble home in the exclusive Vedado neighborhood of Havana, and maintain his car and chauffeur. Because of travel restrictions instituted by the Castro government, he became isolated from his friends and colleagues in American baseball, who quickly lost track of his whereabouts.

One of González’s last reported public appearances was at the final game of the World Amateur Baseball Championship in Havana in January 1972. A Havana newspaper reporter covering the event wrote for The Sporting News, “Now 81 years old, Miguel Angel still has a strong voice, recalls his lifetime baseball records, and his keen eyes observe everything on the diamond.”13

González’s was last heard from when Preston Gomez returned from a visit to Cuba with pictures taken at González’s 85th birthday party. He is seen smiling from behind a large birthday cake, holding a bottle of beer in each hand. He is missing his toes, suggesting that he suffered from diabetes.

González was married twice. After his first wife, Esther, died of cancer, he took his mother, Juana Cordero, into his home in the Havana suburb of Cerro. He later remarried and had a son, Miguel Jr., with his second wife, who was still alive when he died on February 19, 1977, from a heart attack at the age of 86. He is buried in the Christopher Columbus Cemetery in Havana.

This biography is included in the book “The 1934 St. Louis Cardinals: The World Champion Gas House Gang” (SABR, 2014), edited by Charles Faber. It also appears in “Winning on the North Side: The 1929 Chicago Cubs” (SABR, 2015), edited by Gregory H. Wolf.

Sources

Billheimer, John, Baseball and the Blame Game: Scapegoating in the Major Leagues. (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co, 2007). Bjarkman, Peter C., A History of Cuban Baseball 1864-2006 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co, 2007).

Figueredo, Jorge S., Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co, 2011).

Gonzalez Echevarria, Roberto, The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001).

McNeill, William F., Black Baseball Out of Season: Pay for Play Outside of the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co, 2007).

Perez, Louis A. Jr., On Becoming Cuban: Identity, Nationality and Culture (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1999).

Riley, James A., The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994).

Ruck, Rob, Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latin Game (Boston: Beacon Press, 2011).

Stockton, J. Roy, The Gashouse Gang (New York: Bantam Books, 1948).

Broeg, Bob. “Ex-Cardinal Gonzalez Added Accent to Coaching,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 19, 1971.

—— “Mike Gonzalez – Smart Dummy Coach,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 29, 1972.

—— “Mike, She’s Gone – Grins Linger,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 30, 1977.

Hamilton, Jim, “Gonzales (sic) Made Views Known,” Oneonta (New York) Daily Star, August 25, 1985.

Holmes, Thomas, “Aged Gonzales (sic) Returns to St. Louis to Teach Cardinal Kid Pitchers,” Brooklyn Eagle, January 25, 1931.

McKenna, Brian, “The Henriquez Long Branch Cubans,” Baseballhistoryblog.com, accessed June 25, 2013.

Stockton, J. Roy, “Mike Gonzales (sic), He Coach Third Base and Keep Cardinals from Fumbling Around This Year,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 17, 1934.

Ward, John J., “Gonzales (sic), the Cuban Backstop,” Baseball Magazine, February 1917.

—— “Cuba’s Best Catcher With the Cubs,” Baseball Magazine, July 1927.

“Gonzalez, Miguel Angel (Mike),” no author, title or date given. From González’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Karst, Eugene F., “Cardinal Newcomers for 1931,” undated press release from St. Louis Cardinals.

Peal, William H., Letter to Louis Heilbroner, February 5, 1914.

Baseball-reference.com

Notes

1 William H. Peal, letter to Louis Heilbroner. February 5, 1914.

2 John J. Ward, “Gonzales (sic), The Cuban Backstop.” Baseball Magazine, February 1917.

3 Jim Hamilton, “Gonzales (sic) Made Views Known.” Oneonta (New York) Daily Star, August 25, 1985.

4 Thomas Holmes, “Aged Gonzales (sic) Returns to St. Louis to Teach Cardinal Kid Pitchers,” Brooklyn Eagle, January 25, 1931.

5 Joe Massaguer, personal interview with Miguel González. Quoted in The Sporting News, January 23, 1930.

6 Bob Broeg, “Mike, She’s Gone – Grins Linger,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 30, 1977.

7 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Mike Gonzalez – Cuban Caballero of the Cardinals,” The Sporting News, October 20, 1938.

8 Miguel Angel (Mike) “González,” No author, title or date given. From González’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

9 John Billheimer, Baseball and the Blame Game: Scapegoating in the Major Leagues, 14.

10 United Press, “Card Coach Job Given Up by González,” October 17, 1946.

11 Miguel Angel (Mike) “González,” from González’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

12 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Mike González – Cuban Caballero of the Cardinals,” The Sporting News, October 20, 1938.

13 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Mike González Attends Title Contest in Havana. “ The Sporting News, January 22, 1972.

Full Name

Miguel Angel Gonzalez Cordero

Born

September 24, 1890 at La Habana, La Habana (Cuba)

Died

February 19, 1977 at La Habana, La Habana (Cuba)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.