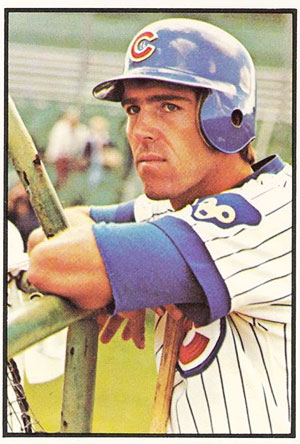

Mike Gordon

In the late 1970s Mike Gordon played a dozen games as a catcher for the Chicago Cubs. Gordon epitomized the huge challenge faced by 18-year-old high-school players to advance through the minor leagues to become a major leaguer. While Gordon’s strong work ethic enabled him to overcome the obstacles to briefly play in the major leagues, many other high-school hopefuls languished in the minor leagues during the 1970s, a period when major-league teams began to switch their preference from selecting high-school players to college players in the amateur draft.

In the late 1970s Mike Gordon played a dozen games as a catcher for the Chicago Cubs. Gordon epitomized the huge challenge faced by 18-year-old high-school players to advance through the minor leagues to become a major leaguer. While Gordon’s strong work ethic enabled him to overcome the obstacles to briefly play in the major leagues, many other high-school hopefuls languished in the minor leagues during the 1970s, a period when major-league teams began to switch their preference from selecting high-school players to college players in the amateur draft.

Michael William Gordon was born on September 11, 1953, in Leominster, Massachusetts, the son of Francis and Carol (Tyler) Gordon. The Gordon family soon relocated to Brockton, 20 miles south of Boston, where Mike grew up with his four siblings, Rebecca, Peter, Richard, and Charles. Mike was the quintessential three-sport athlete at Brockton High School, as co-captain of the football, basketball, and baseball teams. Arguably, Gordon was a better football player than a baseball player. He was selected to the Parade Magazine national All-America high-school football team and signed a letter of intent to play college football at West Virginia University.1 He also had football scholarship offers from Boston College and Notre Dame.2 Although he had no similar credentials as a baseball player, not even a selection to the regional Boston Globe all-scholastic team, Gordon chose baseball over football after the Chicago Cubs drafted the switch-hitting catcher in the third round of the June 1972 amateur draft, the number 63 overall pick.

The swaying factor for Gordon was likely the hefty signing-bonus money paid to high picks in the baseball draft as compared to the uncertainty of a career in pro football after four years of college football. Although the precise amount of his signing-bonus is unknown, Gordon likely received a bonus from the Cubs in the $25,000 to $30,000 range. This is comparable to the $35,000 signing bonus the Montreal Expos paid catcher Gary Carter, a higher third-round selection in that year’s draft.3 Carter, a future Hall of Fame selection, faced the same dilemma as Gordon as a recent high-school graduate. Carter ultimately chose minor-league baseball over college football at UCLA, based on the greater chance of injury in football and his doubts about being “NFL material.”4

Cubs scout Lennie Merullo highly recommended Gordon, as well as four other New England players whom the Cubs selected in rounds nine through twelve of that draft.5 Merullo saw raw potential in the 18-year-old, 6-foot-3, 215-pound catcher, but Gordon was clearly a four- or five-year project to make the Cubs and eventually succeed 30-year-old Randy Hundley, the Cubs catcher since 1966. Merullo’s opinion of Gordon’s potential with the Cubs turned out to be overzealous, during this era of preference in the amateur draft for high-school players (to develop within a team’s farm system) over college players (who were shunned unless they could be projected to be major-leaguers within a year or two).6 Gordon signed with the Cubs days after the 1972 draft and was assigned to their rookie-level team in the Gulf Coast League.7

Gordon advanced slowly in the Cubs minor-league system. After hitting a weak .194 in the Gulf Coast League in 1972, he batted a paltry .180 in each of the next two years at Single A, at Quincy (Illinois) in the Midwest League in 1973 and at Key West (Florida) in the Florida State League in 1974. Given his past experience in short seasons in the cold-weather environment of Massachusetts, Gordon clearly struggled compared with players who came from warm-weather climates. Fortunately, his catching skills helped him to avoid being released after three poor seasons as a hitter in the minors, as the Cubs gave him additional chances in an attempt to recoup their initial bonus-money investment in him. However, the future timeline was short, since by 1974 the Cubs had already moved on from Hundley as their catcher (trading him after the 1973 season). The Cubs acquired Steve Swisher and George Mitterwald to be their new backstop corps for the 1974 season.

Destined for a third consecutive season in Single A, Gordon implemented a self-improvement program two months before the start of spring training in 1975. “After that third disastrous season, Mike launched a do-it-yourself batting program,” Chicago sportswriter Ed Prell wrote, where Gordon, working out with the Eckerd College baseball team (where his brother Chuck played), swung at several hundred pitches each day to improve his batting eye.8 The extra hitting paid dividends, as Gordon hit .241 for Key West in 1975 to earn a promotion to Midland (Texas) of the Double-A Texas League, where he hit .247 during the 1976 season.

Following additional schooling in the Arizona Instructional League in the fall of 1976, Gordon became the Cubs’ top prospect at catcher during 1977 spring training. He leapfrogged two college catchers, as Ed Putman, a 1975 draft pick, was assigned to the Cubs’ top farm team in Wichita (Kansas) of the Triple-A American Association, and Steve Clancy, a 1973 draft pick and the Wichita catcher in 1976, was released.

Gordon had a brief major-league cup of coffee with the Cubs during April 1977 when he made the Cubs roster in spring training as a third-string catcher to back up Mitterwald and Swisher. He caught a few innings of two games, going 0-for-4 at bat, before he was shipped out to Wichita. After he hit .228 at Wichita, the Cubs recalled Gordon when rosters expanded in September. Gordon was inserted into the starting lineup for the September 14 and 15 games at Montreal. According to Chicago Tribune sportswriter Richard Dozer, the Cubs lost both games “because they have committed themselves to finding out what Mike Gordon, a rookie catcher, can do for them next year.”9 Gordon went 0-for-7 in the two games and, more ominously, he allowed six stolen bases in six attempts. Gordon played in four more games, three as the starting catcher, but his hitting continued to be impotent. His hitless streak with the Cubs in 1977 extended to 12 at-bats before he collected his first major-league hit on September 26 in at-bat number 13. Then the cold bat continued as he finished the season 1-for-23 at the plate for a .043 batting average.

Gordon’s subpar performance during the brief stint with the Cubs in September 1977 torpedoed his future in the major leagues. During the offseason, the Cubs made wholesale changes at the catcher position for the 1978 season, to replace Swisher (traded) and Mitterwald (free agent), who had been the catching duo for the previous four years. However, Gordon was not in the Cubs’ long-term plans. To replace Swisher and Mitterwald, the Cubs executed trades to acquire veteran catchers Dave Rader and Larry Cox to be their catchers for the 1978 season.

For the 1978 season, Gordon returned to Wichita, where he shared the catching with newly acquired Tim Blackwell, who had some major-league experience. When Rader was injured in July 1978, the Cubs recalled Gordon, who appeared in four games and went 1-for-5 at bat. However, two weeks later, the Cubs returned Gordon to Wichita and recalled Blackwell, who stayed with the Cubs for the rest of the 1978 season. Putman was no longer competing with Gordon, as he converted from catcher to third baseman, and was soon traded to Detroit.

After the 1978 season, while Gordon was still nominally the Cubs’ top catcher in the minors, the club had selected catcher Bill Hayes in the first round of the June 1978 amateur draft (the number 13 overall pick), following his outstanding season at Indiana State University. Hayes was yet another highly touted college catcher, along with Greg Keatley (a 1976 draft pick), who was breathing down the back of former high-school catcher Gordon to be a future backstop with the Cubs. During the mid-1970s, college players became more highly prized as selections in the amateur draft, replacing the former desire to draft high-school players. “The business of holding the line on bonuses [paid to draft picks] began to lead to an influx of talent to college baseball,” John Manuel wrote in his history of baseball’s amateur draft. “Players who turned down what they thought were insufficient offers out of high school found their way to NCAA play. It led to a golden era for college baseball.”10 With more talented student-athletes than in the past, college competition now better prepared players to excel at professional baseball than did high-school competition followed by years in the lower minor leagues.

In spring training in 1979, there seemed to be a small opening for Gordon to make the Cubs. During the offseason, the Cubs traded both Rader and Cox, their backstop tandem in 1978. Catcher Barry Foote was acquired in the Rader trade. However, Gordon couldn’t seize the opportunity for the second catching spot, which was won by Blackwell. Gordon returned to Wichita one more time for the 1979 season, and he and Keatley shared the catching duties. Gordon, though, was no longer in the Cubs’ plans. When rosters expanded for September, the Cubs acquired catcher Bruce Kimm from Detroit rather than recall Gordon. When Foote and Blackwell remained the catching twosome in 1980, the Cubs released the 26-year-old Gordon at the end of spring training.11

Gordon wasn’t the only catching prospect to fizzle with the Cubs. None of the college catchers drafted by the club between 1973 and 1980 became the future catcher for the Cubs in the 1980s. In December 1980 the Cubs obtained Jody Davis from the St. Louis Cardinals in the Rule 5 draft. Davis became the Cubs catcher from 1981 through the 1987 season.

After eight years in the minors (.216 lifetime batting average) and just a few weeks with the Cubs for only 12 games, Gordon abandoned his quest to be part of the “lovable losers” in Chicago and moved on with the rest of his life. His .071 batting average in the major leagues (2-for-28) doesn’t do justice to the effort Gordon expended to overcome substantial obstacles to reach his goal of being a major-league ballplayer.

After returning to his hometown of Brockton, Gordon married Joanne Ruggerio and they raised two children, Ryan and Rachel.12 He worked as a technician for the Bay State Gas Company (renamed Columbia Gas in 2010) for nearly three decades. He maintained his passion for baseball as a Boston Red Sox fan and satisfied his desire for athletics in a low-key manner as a golfer. He was a member of the Thorny Lea Golf Club in Brockton, where he played in many local tournaments. He devoted much of his time to simply spending time with his family.

In the fall of 2013 Gordon was diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia.13 He fought a valiant eight-month battle with the disease before succumbing to it. Gordon died on May 26, 2014, at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston. He is buried at Pine Hill Cemetery in West Bridgewater, Massachusetts.14

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by David Kritzler.

Notes

1 “WVU Signs Nine More Top Football Prospects,” Morgantown Dominion News, May 21, 1972.

2 Joseph Markman, “Brockton High Sports Star Made Majors Before Returning Home,” Brockton Enterprise, May 30, 2014.

3 Gary Carter and Phil Pepe, Still a Kid at Heart: My Life in Baseball and Beyond (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2008), 14-15.

4 Ibid.

5 Peter Gammons, “Dopfel, Gordon 3d-Round Draftees,” Boston Globe, June 7, 1972.

6 Peter Gammons, “Chalk Up Chalk as No. 1 Free Agent,” Boston Globe, June 4, 1972.

7 “Cubs Sign 4 Selected in Recent Draft,” Chicago Tribune, June 9, 1972.

8 Ed Prell, “Cubs Impressed by Persistent Kid,” The Sporting News, November 6, 1976.

9 Richard Dozer, “Cub Experiment Fails,” Chicago Tribune, September 16, 1977.

10 John Manuel, “The History and Future of the Amateur Draft,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Summer 2010: 62.

11 “Pro Transactions,” The Sporting News, April 19, 1980.

12 Obituary of Gordon, Brockton Enterprise, May 28, 2014.

13 Markman, “Brockton High Sports Star.”

14 Obituary of Gordon.

Full Name

Michael William Gordon

Born

September 11, 1953 at Leominster, MA (USA)

Died

May 26, 2014 at Boston, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.