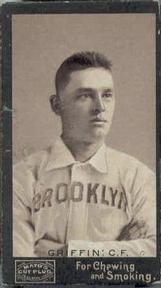

Mike Griffin

On April 16, 1887, Michael J. Griffin stepped to the plate in the first inning of a game between the Baltimore and Philadelphia clubs of the American Association. In his first major league at-bat, Griffin entered the record books by homering off Philadelphia’s Ed Seward. Griffin became either the first or second player to homer in his first major league at-bat. George Tebeau of Cincinnati also accomplished the feat on the same day. Research has yet to determine which was “officially” first.

On April 16, 1887, Michael J. Griffin stepped to the plate in the first inning of a game between the Baltimore and Philadelphia clubs of the American Association. In his first major league at-bat, Griffin entered the record books by homering off Philadelphia’s Ed Seward. Griffin became either the first or second player to homer in his first major league at-bat. George Tebeau of Cincinnati also accomplished the feat on the same day. Research has yet to determine which was “officially” first.

While it wasn’t a portent of Griffin becoming a great home run hitter, that first time rounding the bases was the beginning of one of the finest careers in 19th century major league baseball. By the time of his unusual “retirement” from the game, he had amassed statistics in several categories that put him with the elite players in baseball history. At 5-feet-7 and 160 pounds, he didn’t have much power. He did have speed, as shown by his lifetime total of 473 stolen bases.

Mike Griffin was born March 20, 1865, in Utica, New York, to Patrick and Ellen Griffin. Patrick Griffin was a cigarmaker who would teach his son the trade during baseball’s off-season. Patrick also served as Treasurer for the City of Utica.

Mike grew up playing baseball in Utica parks for the Nine Spots, throwing right-handed, but batting left-handed. In 1884, the 19-year-old Griffin played for a Utica club that was one of the finest amateur teams in New York State. Three members of this team (Griffin, Hank Simon, and Dave McKeough) would play in the major leagues. The success of this team encouraged Uticans to field a professional team.

In 1885, the core of this amateur team became professional for the new Utica entry in the New York State League (NYSL). On September 25, Mike Griffin won the standing prize of $30 and a silver-headed cane from Utica’s baseball fans by hitting the first home run of the season at Utica’s Riverside Park. Griffin hit a long drive to the outfield and slid home just ahead of the throw for what turned out to be the only homer hit at Riverside that year. Riverside’s spacious outfield extended to 450 feet in left and center fields. The team finished third in the league with Griffin batting .280 in his first pro season.

Prior to the 1886 season, the NYSL added two Canadian teams, Hamilton and Toronto, and the International League was born. Utica retained many of the previous season’s players, including Mike Griffin.

Utica won the International League pennant with a 62-34 record, and Griffin was an important part of the team. He hit nearly .300 with 34 stolen bases and posted the 3rd highest fielding percentage among International League outfielders. The 2nd highest percentage was achieved by teammate Sandy Griffin. Sandy, who was not related to Mike, may have contributed to Mike’s making it to the major leagues.

Late in 1886, Manager Billy Barnie of Baltimore in the American Association came to Utica to scout Sandy Griffin. There was some debate at the time as to whether Barnie was impressed by Mike or just confused the two players. Over a decade later, Barnie was still telling people that no mistake was made, that he had been scouting all players and was impressed by Mike. In any case, during the offseason Mike Griffin was signed to play for Baltimore in 1887. He had gone from amateur to major leaguer in three years.

While Griffin homering in his big league debut at-bat was noted in the newspapers of the era, it wasn’t considered a historical accomplishment. Probably nobody at the time had any idea whether the feat had been accomplished before or not.

Mike Griffin’s rookie season was an unqualified success. In the 136-game season, he hit .301 with 32 doubles, 13 triples, 3 home runs, 94 RBI (his career high) and 142 runs scored. He also stole 94 bases, the highest total for a rookie until Vince Coleman stole 110 in 1985.

In 1889, Griffin led the American Association with 152 runs scored in 137 games. This is one of the highest “average runs per game” totals in major league history. When Billy Hamilton set the major league record of 192 runs in 1894, he averaged 1.49 runs per game. Babe Ruth’s modern-day record of 177 runs, in 1921, produced an average of 1.16 runs per game. Griffin’s average of 1.11 in 1887 puts him among the all-time leaders.

After three seasons in Baltimore, Griffin joined the Philadelphia team in the upstart Players League in 1890. His 10 double plays led all league outfielders. The following season, Griffin joined Brooklyn’s National League team and promptly led the league with 36 doubles. In 1892, he scored over 100 runs for the sixth time in his six big league campaigns.

Griffin remained with Brooklyn for the rest of his career; continuing to put up good offensive numbers. In 1894, he hit a career-high .357 with 123 runs in just 108 games, an average of 1.14 runs per game. The next season he hit .332 with 140 runs. He was the leadoff hitter in the order and a leader on the field. He became team captain in 1895 and would hold that position for the rest of his career.

In his 12 major league seasons, Griffin scored more than 100 runs ten times, a mark reached by only 17 players in history. He also accomplished the equally rare feat of averaging more than a run a game in six different seasons. His final five seasons, he hit .300 or better and finished with a lifetime average of .296. As of this writing (after the 2003 season), his 1406 runs scored rank him 73rd all-time and his 473 stolen bases place him 41st.

Griffin was often called the finest center fielder of his era. Five times he led the National League in fielding percentage for outfielders. He also led in putouts two times.

Brooklyn was struggling in 1898, and manager Bill Barnie was released. Team captain Mike Griffin took over the reigns of the club as player-manager for four games-posting a 1-3 record-before quitting as manager and turning the reigns of the club to new team president, Charles Ebbets. Griffin continued playing for Brooklyn under Ebbets.

After the season ended, Griffin signed a contract with Brooklyn to be player-manager for the 1899 season with a salary of $3,500. Little did he know, he would never set foot on a major league diamond again.

The Brooklyn franchise was floundering, posting a 54-91 record in 1898 and drawing the third worst attendance in the National League. So Charles Ebbets merged the team with Baltimore’s club. Baltimore’s manager was future Hall of Famer Ned Hanlon, who was retained to manage the new combined team.

Mike Griffin was offered a salary of $2,800 to be only a player instead of a player-manager. He refused the offer, saying he had a valid contract for $3,500 and expected it to be honored. It is likely he realized the “new” Brooklyn team was considerably better than the 1898 version, and he had looked forward to managing what promised to be a successful team. In none of his previous twelve major league seasons had he played for a pennant-winning ballclub.

The dispute dragged on with neither side willing to give in. Players had very few rights in this era, so owners were used to holding the upper hand. On March 11, 1899, Ebbets sent Griffin the following telegram: “You have been released to the Cleveland club. They wish you to report to Cleveland on Monday, to go with team to Hot Springs. Personally I wish you the best of luck in your new position.” Griffin also received a telegram from Cleveland manager Patsy Tebeau that said, in part, “Mr Robinson has purchased your release from Brooklyn.”

Griffin refused to report to Cleveland until his contract dispute with Brooklyn was resolved, because it appeared unlikely that Cleveland was going to pay the $3,500 salary that Griffin felt he was entitled to. For two weeks, letters and telegrams were exchanged between Griffin (at home in Utica), Cleveland, and Brooklyn. Cleveland finally had enough and released Griffin to St. Louis. This mattered little to Griffin as his beef was still with Brooklyn. He didn’t report to St. Louis-he never played professional baseball again. In mid-April he announced his retirement from baseball.

Griffin filed suit against Brooklyn for breach of contract. Judge William Scripture of the New York State Supreme Court ruled in Griffin’s favor and awarded him $2,266. Brooklyn appealed, with John M. Ward arguing their case. Ward was a former ballplayer who was one of the founders of the Players League that had challenged, unsuccessfully, the supremacy of the “Lords of Baseball,” the owners.

The justices on the appeals court sided with Griffin. In fact, they said that Brooklyn not only didn’t have grounds to win an appeal, they were fortunate with the initial ruling because the judge should have awarded Griffin several hundred dollars more in damages.

His career in baseball ended, Griffin went into business in Utica. He was a part owner and vice-president of the Consumers Brewery and then later an agent for the Gulf Brewery. His interest in the business had begun during his playing career when he spent some winters doing brewery business in Watertown, New York, for the firm of Barney and Welch.

Mike Griffin also stayed involved with baseball. When he appeared in the Utica grandstand on Opening Day of the New York State League season of 1899, the crowd cheered itself hoarse. The following season, he was vice-president of the Utica Base Ball Association, operators of the New York State League Champion Utica Reds ballclub. It was also a good year for Griffin personally. On June 20, 1900, Griffin married Margaret Elizabeth Barney.

Griffin was a respected member of the Utica Elks, serving as exalted ruler for a year. He also would umpire charity games and always received much applause from fans.

In April of 1908, Griffin became ill with pneumonia, and his condition rapidly deteriorated. On April 10, the 43-year-old Griffin passed away. He was survived by his wife, Margaret, and three children, Margaret, Robert and Helen.

While largely forgotten by history, Mike Griffin remains one of the finest players of the 19th century. Of the 17 players who scored 100 runs in at least 10 seasons, only two of those eligible for the Baseball Hall of Fame have not been inducted-Mike Griffin and George Van Haltren.

Sources

My sources were the biographical sketch of Griffin written by Richard A. Puff and Mark D. Rucker that appeared in the SABR publication Nineteenth Century Stars (1989), and numerous items that appeared in the following Utica, New York, newspapers: Sunday Tribune, Daily Press, and Observer.

Photo credit: Mike Griffin, Trading Card Database.

Full Name

Michael Joseph Griffin

Born

March 20, 1865 at Utica, NY (USA)

Died

April 10, 1908 at Utica, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.