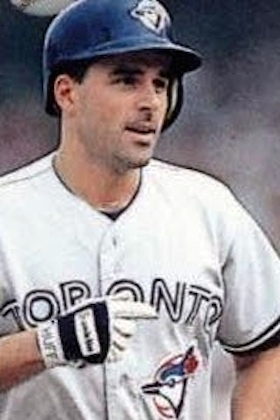

Mike Huff

If the movie Cinderella Man had been about the career of a major league baseball player rather than a boxing legend, the story of Mike Huff would have to be considered. His good friend and former college teammate Joe Girardi would probably agree. “Mike has had a lot of adversity in his life but he gets through it.”1

If the movie Cinderella Man had been about the career of a major league baseball player rather than a boxing legend, the story of Mike Huff would have to be considered. His good friend and former college teammate Joe Girardi would probably agree. “Mike has had a lot of adversity in his life but he gets through it.”1

Michael Kale Huff was born August 11, 1963, in Honolulu, Hawaii. He was the first of three children of sports-minded parents, Bob and Karen Huff. “My parents met as freshmen in the same English class at the University of Hawaii.” said Huff.2 Bob Huff won four letters as a member of the school’s basketball and track teams. Karen, a member of the Fighting Rainbows track and field team, was the 1961 and 1962 women’s national champion for the javelin throw, and surpassed the Los Angeles Coliseum javelin throw record set by legendary Babe Didrikson.3 “Mom was all set to try out for the 1964 Olympics. But then I was born. That sort of ended that idea.”4

At the age of seven months, Huff had his first mishap when hit by a car, cracking two of his ribs. “They were worried that the ribs weren’t going to grow back together,” said Huff. “That would have meant (the end of) sports.”5 Luckily, Huff recovered from the accident, which could have been a lot worse. “My parents were told that if it had happened when I was three months younger, my ribs would have been separated. Had it been three months sooner, my lungs would have been punctured.”6 Seven years later Huff had another setback when struck by a car again. “It happened when I ran between two cars.”7

After Huff’s parents earned their degrees at Hawaii, they moved to Boston to further enhance their educations. Bob attended Harvard to get his master’s degree in business; Karen went to Boston University to obtain her advanced degree in education. In 1965, the Huffs moved to Wilmette, Illinois (a Chicago suburb), where Bob took a job with Bell & Howell and Karen worked in education, and later coached the Evanston high school track team. Two additions to the family came with the birth of a girl in 1970 (Malia) and another boy (Matt) one year later.

Fully recovering from his toddler-age injuries, Huff went on to excel in the Wilmette Park District’s sports program. In 1977, he entered prestigious New Trier East High School (in Winnetka, Illinois), where he played football, basketball, and baseball, and starred in all three sports. Although his future would be in baseball, football was said to be his best sport, but basketball, his “weakest sport,” was his favorite. “It’s probably because of my dad,” said Huff.8 That’s because Bob Huff installed a basketball hoop in the driveway and enjoyed shooting hoops. “He (dad) was 6’4 ½, could palm a basketball, had a 39” vertical leap and could dunk two basketballs at the same time.”9

While in high school, Huff had the pleasure of playing for three (Illinois) Hall of Fame coaches. Former NFL defensive back Eugene “Chick” Cichowski was head coach of the Indians’ football program. John Schneiter (the only basketball coach in Illinois high school history to lead both boys’ and girls’ teams to the state championship game) was the head basketball coach, and Ron Klein ran the baseball team.

“(Coach) Cichowski taught me that I could play through pain and injury, and that I could take my game to the next level if I listen to my body. John Schneiter was a prankster and was sarcastic, and he’d push you and made sure that you thought on the court. Ron Klein was a great fundamentals coach. From him I learned dedication and to love the sport. He taught us to think how we can get an edge to help the team win. He drove me to play hard and to never give up.”10 During his junior year the Indians baseball made it as far as the state tournament’s semifinals, with Huff accumulating the most hits in that state tournament.11

In the fall of his senior year, Huff received several college football scholarship offers (to play defensive back). With Huff as the starting quarterback and safety, the Indians edged their way up to the second-highest ranking in the nation, and soon there was talk within the community about Huff and the Indians winning the state championship. “I really think we can do it,” said Huff.12 But during a key win over highly rated Deerfield High School, Huff sustained a knee injury while running between two opposing linemen. A week later, with their star quarterback out of the lineup, the Indians lost by a point. Then came another bad break when the New Trier East faculty voted to go on strike, thus jeopardizing the rest of their football season. The strike was luckily resolved after a week, and Huff, with his knee tightly taped, returned to the lineup. However, the layoff during the teacher’s strike hurt in the long run. The Indians lost their first game of the state playoffs to the team that would win the state championship.

During the hoops season, Huff began to look at college football programs. “Our basketball games were on Friday and Saturday evenings, so I had to visit colleges on Sundays and return home on Mondays.”13 As he began to think about his collegiate athletic options, the Indians basketball team began to jell through the state tournament. With Huff playing a key role as starting point guard, the Indians won their regional and sectional championships to advance to the super-sections to take on powerful rival Evanston Township, which featured a lineup of four major college basketball signees.

A few days before the big showdown, tragedy struck when Malia, Huff’s kid sister, was diagnosed with leukemia. “I remember a classmate of mine was diagnosed with the same kind of leukemia in third grade, and he died three years later.”14 A few days later, with his sister in his thoughts, Huff and the Indians trailed Evanston until the game’s final minute. After the Indians took a one-point lead late in the game, Huff came up with a “clean steal” and then made a beeline to the basket.15 He was fouled while attempting a layup on the play, then made one of two free throw attempts to add to the lead. With seven seconds remaining in the game, and the Indians clinging to a three-point lead, Huff made two more free throws to ice the win. “Huff by far played his best game of the year,” Coach Schneiter told the sportswriters after the game.16

A few days later, in the state’s quarterfinals on the home court of Illinois’ Fighting Illini at Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, with New Trier East ahead in the third period, Huff’s tender knee collapsed. As the injured Huff watched the rest of the game from the bench, the opposition rallied to win.

The injury meant the end of Huff’s high school athletic career. Surgery was performed. The doctors discovered that 80% of the anterior cruciate ligament had been ground away, and the remainder was surgically removed. Huff was forced to sit out the entire baseball season, but he did receive one last prep honor when all the other baseball coaches in the conference selected him as honorable mention on the all-conference team.17

After high school graduation, Mike Huff had a decision to make. With an ill family member, he wanted to be close to home, and he considered giving up sports. “My sister said no way, and she encouraged me to keep playing.”18 Luckily, he had emphasized getting good grades; they were strong enough to win admission to one of the finest schools in the nation – Northwestern University, located in nearby Evanston. At Northwestern Huff tried out for baseball and made the team as a walk-on. “I led the team in hitting my freshman year.”19 By the time he graduated – with a degree in computer science – he was the all-time leader for the school in three offensive categories. In fact, Huff did so well (he hit. 366, stole 30 bases, and scored 54 runs in 53 games his junior season) that major league scouts were taking notice.

After another good season his senior year, Huff was drafted in the 16th round of the 1985 draft by the Los Angeles Dodgers. “A Dodgers scout came to my house to sign me. He put a contract on the table for $8,000.”20 Unsure what to do, the Dodgers prospect asked for a moment alone with his dad. The money wasn’t a lot, especially compared to what Huff, who was now equipped with a degree from Northwestern, could make in the business world, and to the $50,000 to $60,000 his undrafted college teammates were offered for starting salaries. Huff had the option to tag along with his collegiate teammates and classmates for the good-paying jobs outside of sports. On the other hand, eight grand was a good salary for a mid-round draft choice fresh out of college. “My dad told us you always have to follow things through to the end.”21 Huff knew there was a path to follow in professional baseball.

Huff was assigned to Great Falls, Montana, the rookie league affiliate of the Dodgers. “That worked out well, because my family took their summer vacations in Montana, and this allowed them to visit and see me play.”22 In his first year of professional baseball, he hit an impressive .316, with a .448 on-base percentage and .389 slugging percentage. He also stole 28 bases. In his second season he hit .293/.408/.370 and stole 28 bases at Vero Beach (Class A). He continued to move up the Dodgers organizational ladder when he was assigned to their Double-A team in San Antonio.

The 1987 season at San Antonio began with promise. By May 10 Huff was hitting .311/.367/.430 and was second on the team in runs scored. He had hit three home runs, driven in 18 runs in 31 games, and was the only player on the team who had played in every inning of the season. In the field, known to never be a problem for Huff, he had made a smooth transition from center to right field and had thrown out three runners at the plate. More significantly, he had learned to go from “a slap to swat hitter,” mostly due to a weight training program the previous winter with Northwestern assistant baseball coach Paul Stevens. “He convinced me I could do more,” said Huff. ‘It gave me a lot of confidence.”23

But then came a mid-May evening in Shreveport. “I get the ‘willies’ just thinking about it,” said Huff. “I’ll never forget it.”24 Huff hit a ground ball to the right side of the infield that was earmarked to go into right field for a base hit. Shreveport Captains first baseman Ty Dabney dove and managed to pluck the groundball with his glove hand. It was then a foot race to the first base bag. Huff, after sprinting down the line, stretched for the base, fell, and hyperextended his left knee, the same knee he had injured during his high school days. He then felt the knee collapse to the inside. He was carted off the field on a stretcher and rushed to a local hospital. He had stretched and torn the medial collateral and posterior ligaments in the knee. Doctors at the Shreveport hospital, and later in San Antonio, told him, “You have to be prepared for the fact that it might be over.”25

“So here I was performing, putting the right numbers up,” said Huff, “and all of the sudden a freak play. I couldn’t believe it was going to end this way.”26 In the second arthroscopic surgery of his athletic career, Huff lost 30% of the meniscus and a chunk of bone on his lower leg. Following the procedure, Huff asked the Dodgers organization for permission to recover at home, which was granted.

While recovering with his family in Wilmette, Huff had a chance to watch his brother, Matt, begin his varsity athletic career at New Trier high school. His sister, now a senior in high school, and fully recovered from her illness, was a member of the New Trier track team. “It brought back memories,” Huff said. He also added that it was “therapeutic.”27

Huff spent the rest of the summer, fall, and winter getting his knee back into shape. He worked hard and visited Physical Therapy LTD on a weekly basis to work his knee back into shape. He also continued to work his off-season jobs at Baxter Labs and Rank Video, and earned another degree at Northwestern University (Bachelor of Science) in industrial engineering. And he never lost sight of his goal to make it to the majors. “I know baseball is not going to end right now. This just doesn’t seem like the end.”28

Huff returned to San Antonio in 1988, and he bounced back to have another great season. He hit .304/.370/.415, stole 34 bases, and was a league All-Star. He performed so well that the Dodgers promoted him to their Triple-A club at the end of the season. Four months after the season, Huff married the former Camille Jenkins. They would have three daughters: Taylor, Brianna and Sheridan.

In 1989, Huff was back at the Dodgers’ Triple-A team in Albuquerque and had another All-Star season, hitting .318/.368/.473 with 32 steals and a career-high ten home runs. The Dodgers rewarded him by calling him up to the major leagues in August. “I was living a dream,” Huff recalled. “I walked into the clubhouse, and there was my locker with my name on it…my uniform with my name on it, the letters sewed on.”29

On August 7, in a home game versus the Atlanta Braves, Huff was sent to the plate as a pinch-hitter for Mike Scioscia in the bottom of the eighth, with the Braves clinging to a 1-0 lead. As he was about to step into the batter’s box for his first major league at bat, he heard the home plate umpire, “Country” Joe West, say, “Hey wait a minute, kid, what do you think you’re doing?”

“What am I doing,” Huff thought to himself. “I am wearing a major league uniform. I have my own number, my name sewed on the back and I am playing in Dodger Stadium. I am living my dream, that’s what I am doing.”30

Huff then attempted to step into the batter’s box when umpire West warned him a second time. “Hey kid, what are you doing? I have not pointed to indicate for the public address announcer to announce you.”31 West then motioned to the press box to announce Mike Huff as a pinch hitter. As Huff’s name echoed throughout the stadium, he then stepped into the batter’s box, looked toward the pitcher’s mound, and saw Braves ace Tom Glavine. “I figured he knew I was a rookie, so he would try to blaze a few fastballs by me for an easy strikeout.” But Glavine threw a curve instead. Huff swung, connected, and launched a hit into the outfield. As Huff stood on first base after making his first big league hit in his first ever major league at bat, Glavine looked him over, “as if to say, ‘Hey kid, don’t you know that a rookie is supposed to be looking for a fastball?’”32

Huff played in 12 games in the month of August 1989. He made five hits, including a double and his first major league home run.

In 1990, Huff figured he had a good chance of making the Dodgers roster for the entire season. However, his hopes were upset by the owners’ lockout. “They never really got a chance to look at me,” during the abbreviated spring training.33 He was sent back to Albuquerque for the entire season. Huff responded by having his best season in professional baseball, hitting .325/.420/.475, scoring 99 runs, with 28 doubles and 84 RBIs. Once again, he was a league All-Star, and his team won the Pacific Coast League championship.

Prior to the 1991 season, Huff, concerned about his chance to return to the major leagues as a Dodger, made a request. “I asked the Dodgers if they could leave me off the 40-man roster.”34 They did, and on December 3, 1990, the Cleveland Indians claimed him in the Rule 5 Draft.

Back in the major leagues when the 1991 season began, he was happy to be in a new city. “I like it here in Cleveland,” he said. “It reminds me of the Chicago area. It’s located along a lake.”35 Also while in Cleveland, he received the greatest compliment of his career when a couple told him that they were going to name their newborn in his honor. “They named their son Kile (after Huff’s middle name). My middle name is Hawaiian, and the Hawaiian (pronunciation is ‘Kay-lie,’ not ‘Kyle’).”36 Not wanting to hurt any feelings, Huff did not mention the correct pronunciation, but still felt honored.

In 51 games during the first half of the season at Cleveland, Huff was hitting .240/.364/.336. One day when the Indians were in Seattle, Huff returned to his hotel room after having lunch with a cousin. He noticed the light on the phone in his hotel room was lit. He followed up and spoke with John Hart, the operations director of the Indians, who informed him that he had been placed on waivers and instructed him to go to team manager Mike Hargrove’s room to fill out paperwork.

Feeling dejected, Huff picked up the phone to call his wife to tell her the news, but just as he picked up the receiver, Dan Evans, a representative of the White Sox, was on the line. He told Huff that the White Sox had claimed him off waivers and were happy to have him. Huff, now feeling excited, went to manager Hargrove’s room, gladly filled out the paperwork and was a member of the White Sox.37

In one of his first games with the White Sox, in a close game versus the Milwaukee Brewers, Huff, playing right field, made “a sensational diving grab” on a fast sinking liner off the bat of Paul Molitor in the top of the ninth of a one-run game.38 “I was happy I made that play to save the game,” Huff recalled. “But in the back of my mind I was also thinking that I justified the White Sox decision to claim me. A few years later, when Molitor and I were teammates in Toronto, he told me he remembered that play.”39

Huff had a good 1991 season in Chicago, hitting .268/.357/.361 and proving to be a good reserve off the bench for a team that finished with 87 wins. The White Sox also had a good season in 1992 with Huff on the team. “That was the season we had a lot of injuries.”40 Huff was among the casualties with a shoulder injury.

The White Sox outfield became crowded in 1993 with the addition of newcomer Ellis Burks and Bo Jackson, returning from injury. Plus, Steve Sax, whom the White Sox had acquired as a second baseman the year before, was converted into an outfielder. To get playing time rather than sit on the bench, Huff was sent to the White Sox Triple-A team in Nashville, where he had a productive season, batting .294/.411/.433.

During the 1993 season, another Huff was in professional baseball. Matt Huff, just like brother Mike, played his collegiate baseball at Northwestern, and was drafted in the 45th round by the Texas Rangers. He hit .276/.351/.478 with eight home runs at Butte, Montana, of the Pioneer League. The following season the Rangers wanted Matt Huff to play another season at Butte, which did not appeal to him. The younger Huff decided to step away from the game.41

During the tail end of the successful 1993 season, with the White Sox closing in on the American League West title, Huff was recalled. On the evening of September 27, the White Sox clinched the division crown, “I was in the game when the final out was made,” said Huff.42 He was also on the Chicago roster for the American League Championship Series against the Blue Jays. The White Sox lost the first two games, but bounced back to take Game Three and Game Four. In Game Five the Blue Jays beat Chicago and starting pitcher Jack McDowell. “When I was with Toronto the following season, I had heard that the Blue Jays were onto McDowell. He was tipping his pitches,” according to Huff.43 The Blue Jays also won Game Six to win the series.

Following the 1993 season, the White Sox nominated Huff for the Roberto Clemente Award, given annually to the player who best exemplifies sportsmanship, community involvement, and a player’s contribution to his team. Also following the 1993 season, Huff received a phone call from Chicago team owner Jerry Reinsdorf. “We have a new outfielder, and I want you to work with him on defense. I can’t tell you who this guy is right now.”

“Great,” Huff thought to himself. “Here I have to grind for the few innings I get to play, and he wants me to train some guy who will probably take my place?” 44 That new outfielder turned out to be NBA superstar Michael Jordan.

Prior to the start of the1994 season, Huff was sent to Toronto, which was a surprise to him. He was to play the same backup role with the Blue Jays that he had filled in Chicago, but ended up playing in 37 more games during a strike-shortened season than he had in the previous season. It was a good year; he hit a career-best .304/.392/.449. He returned to the Blue Jays in 1995, for a season in which he was slowed by leg injuries. He expected to be back with Toronto in 1996, but was sent to Toronto’s Triple-A affiliate. “It’s frustrating to be here,” Huff said at Syracuse. “When you know you have earned a spot at the next level, yet for whatever reason, you know you are not there.”45 He had asked to be traded. A trade was possible with Boston, but that fell through.46

Huff did make it back to the major league team during that season for 11 games and 29 at-bats. But now at the age of 33, with a wife and three daughters, and making less than $30,000 as a minor league ballplayer, Huff knew it was time for a career change. When the 1996 season concluded, Huff stepped away from the game. “It was an easy transition,” he said.47

He went back to Chicago to work in commercial real estate and property management. He then moved to Dallas for a few years where he worked in structure finance. But in the back of his mind he knew he wanted to be in Chicago. He also realized how much he missed sports. Then came the opportunity when Jerry Reinsdorf offered him a job in coaching kids at his White Sox and Bulls training academy. “It is so much more fulfilling,” Huff says about being back in Chicago, sports and influencing young athletes.48

Notes

1 Chicago Tribune, August 11, 1992

2 Mike Huff phone interview, August 13, 2015 (hereafter “Huff phone interview”)

3 Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1992

4 Wilmette Life, September 25, 1980

5 Wilmette Life, August 6, 1987

6 Huff phone interview

7 Huff phone interview

8 Wilmette Life, September 25, 1980

9 Huff phone interview

10 Huff phone interview

11 Wilmette Life, August 6, 1987

12 Wilmette Life, September 25, 1980

13 Huff phone interview

14 Huff phone interview

15 Chicago Triune, March 18, 1981

16 Chicago Tribune, March 18, 1981

17 Huff phone interview

18 Huff phone interview

19 Huff phone interview

20 Huff phone interview

21 Wilmette Life, August 6, 1987

22 Huff phone interview

23 Wilmette Life, August 6, 1987

24 Wilmette Life, August 6, 1987

25 Wilmette Life, August 6, 1987

26 Wilmette Life, August 6, 1987

27 Wilmette Life, August 6, 1987

28 Wilmette Life, August 6, 1987

29 Chicago Tribune, May 13, 1991

30 SABR 45 Convention (Chicago): White Sox Player Panel, June 27, 2015 (hereafter “White Sox Player Panel”)

33 Huff phone interview

34 Huff phone interview

35 Chicago Tribune, May 13, 1991

36 Huff phone interview

38 Chicago Tribune, July 21, 1991

39 Huff phone interview

40 Huff phone interview

41 Huff phone interview

42 Huff phone interview

43 Huff phone interview

45 New York Times, March 5, 1994

46 New York Times, March 5, 1994

47 Huff phone interview

48 Huff phone interview

Full Name

Michael Kale Huff

Born

August 11, 1963 at Honolulu, HI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.