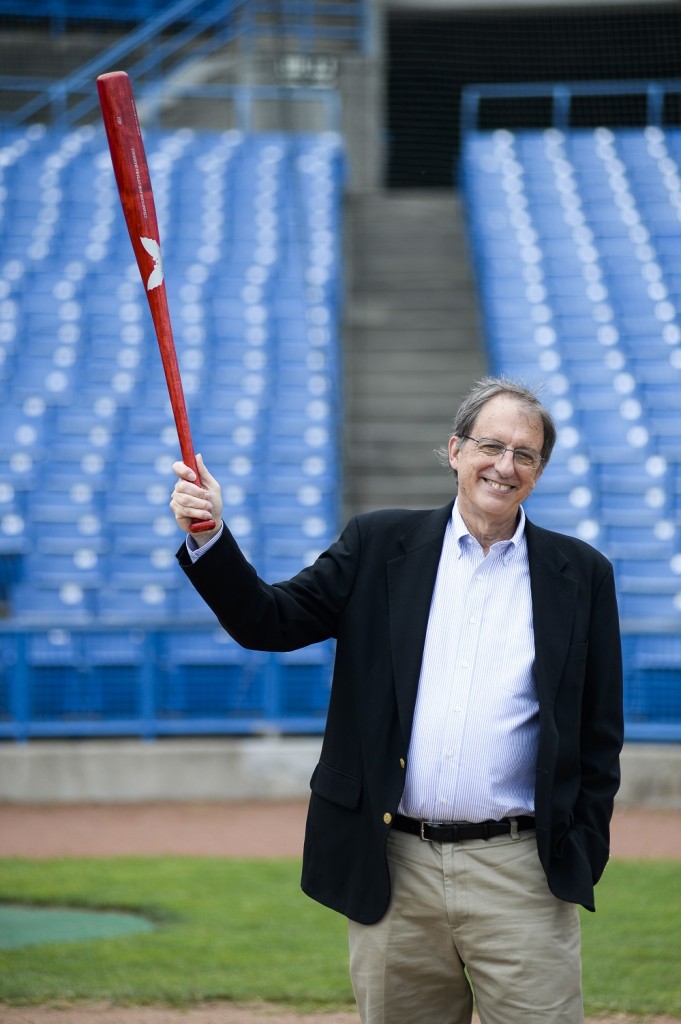

Miles Wolff Jr.

“He’s one of the icons of the industry, no question.” – Dan Moushon, President of the Appalachian League (2020)1

In the early 1970s, Miles Wolff raised a concern about having a career befitting a graduate of Johns Hopkins University. That concern was unfounded. Over the course of half a century as a commissioner, executive, and owner in minor and independent leagues, Wolff had a profound impact on both the sport and business of baseball. In 2014 John Thorn, the official historian for major league baseball, and Alan Schwarz published a list of the 100 most notable people in the history of baseball. Wolff was number 79, just behind Hank Greenberg.2

In the early 1970s, Miles Wolff raised a concern about having a career befitting a graduate of Johns Hopkins University. That concern was unfounded. Over the course of half a century as a commissioner, executive, and owner in minor and independent leagues, Wolff had a profound impact on both the sport and business of baseball. In 2014 John Thorn, the official historian for major league baseball, and Alan Schwarz published a list of the 100 most notable people in the history of baseball. Wolff was number 79, just behind Hank Greenberg.2

In 2020, Dan Moushon stated that Wolff jump-started minor league baseball, showing that a franchise could be fun and profitable, with his 1980 purchase of the Durham Bulls.3 He was then instrumental in bringing the classic baseball film Bull Durham to the screen. Wolff also applied his acumen to various other minor league franchises — not to mention entire leagues. While the journey has been somewhat rocky, there is no doubt that independent leagues have become a significant component of baseball. Today, in 2021, there are four indie circuits — the Atlantic League, Frontier League, Pioneer League, and American Association — that are considered partners of major league baseball. Other independent leagues are also functioning. All of this is mainly because of the vision Miles Wolff had in 1990.

Even more, he boosted the game as a publisher. Baseball America, which he bought in 1981 and sold in 2000, remains the most comprehensive source of all things baseball. After substantial research, in 1993 Baseball America published the first edition of The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, edited by Lloyd Johnson and Wolff.

Miles Wolff was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on December 30, 1943, to Miles Sr. and Anna Webster Wolff. Miles Sr. was managing editor of the Baltimore Evening Sun, one of America’s major newspapers of the 1930s and home to H.L. Mencken. The first position Miles Sr. held with the Evening Sun was as an assistant to Mencken. Wolff’s two older sisters have also been quite successful. Ann had her own CPA firm and Lila received her doctorate in public health from Johns Hopkins.

When Miles was six years old, his father, a native North Carolinian, moved the family to Greensboro, North Carolina, to become the executive editor of the Greensboro Daily News. The distinguished newspaperman also served as president of the American Society of Newspaper Editors (ASNE) and as a member of the Pulitzer Prize jury seven times.4

While living in Greensboro, Miles became an ardent fan of the Greensboro Patriots in the Carolina League. They played their home games in War Memorial Stadium, a classic minor league park built in 1926. In addition to attending many of the home games, Miles at the age of 12 began selling sodas at the games.

Like most boys his age, he had dreams of becoming a professional baseball player. Realizing those dreams might not be fulfilled, he was digesting what made minor league baseball successful. In addition to the true baseball fans, there were attractions at most games that catered to the entire family such as Tropical Pet Night. At about the age of 14, in a conversation with a close friend, Miles said, “Bobby, I can tell you now, I am going to stay in this game for the rest of my life.”5

After high school, he accepted a partial scholarship and attended Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. At Hopkins he majored in history, played basketball, and announced football and lacrosse games for WJHU, the student-run radio station. He also pursued jobs in baseball but to no avail.

After graduating from Hopkins, Wolff decided to pursue graduate studies in Southern History at the University of Virginia. While at Virginia he wrote a master’s thesis on the 1960 sit-ins by four North Carolina A&T students at Woolworth’s in his hometown of Greensboro. That thesis became the basis for his first book, Lunch at the 5&10.6 Pulitzer Prize winner Edwin M. Yoder, writing for Book World, stated, “Wolff has recaptured these days with a sense of their drama, with deft characterizations of the principals, and a sure feeling for the mood…. An extraordinary accomplishment.”7

In 1967Wolff joined the US Navy, serving as a supply officer on the USS Charles P. Cecil and USS Puget Sound.8 The responsibilities associated with being a supply officer enhanced both his resourcefulness and creative problem-solving. These would prove very useful in future endeavors.9 Discharged from the Navy in 1970, Wolff secured his first position in baseball with the Atlanta-owned Savannah Braves. Atlanta decided that new blood was needed to rejuvenate some of their minor league affiliates and called upon Wolff to be Savannah’s general manager, While Atlanta controlled the players, franchise operations were the responsibility of the GM. As such, he learned to grow grass on the infield, roll out the tarp — and, of course, get fans in the stands. He also put into practice the ideas that had been fermenting since Greensboro. After his first year, he was named Class AA minor league executive of the year by The Sporting News.

While enjoying his Savannah experience, Wolff quit after his third season, stating, “I’d done it, now it was time to get a real job. I was a Hopkins grad, I was supposed to do something important. Hopkins doesn’t train minor league general managers.”10 For the next few years, Wolff held a variety of jobs. As a result of his success with Savannah, he took on interim general manager positions in Anderson, South Carolina, and Jacksonville, Florida. He also became the voice of the Richmond Braves of the International League for one season. He continued writing and had a novel published, Season of the Owl, a coming-of-age story set in North Carolina.11

But he still felt that he needed to do something befitting a Hopkins grad, which might mean owning a minor league franchise. In 1980 he said, “No one wanted to own minor league teams at the time. But I figured I knew how to run a club as good as the owners I’d worked for.12

His first thoughts gravitated toward reviving the Macon, Georgia, club in the Southern League — but his attention was quickly diverted to Durham, North Carolina, where the Carolina League was looking for someone to invest in a farm team of the Atlanta Braves. Other suitors with more funds were interested but the Braves, given their experience with Wolff in Savannah, selected him. The franchise cost Miles a mere $2,417.13

Fortunately, Durham had a ballpark, the Durham Athletic Park (the DAP) that could house a team. It had been built in 1939 after the original stadium, El Toro Park, was destroyed by fire. Renovations were necessary because minor league baseball had left Durham in 1970. Wolff convinced the City of Durham to appropriate $50,000 for the necessary upgrades.14 He also raised $30,000 by selling stock to family friends and others for operating expenses.15

With Durham’s Opening Day scheduled for April 15, 1980, some unforeseen events had to be overcome. Just two days before Opening Day, the home team uniforms were stolen. Replacement uniforms were borrowed from Atlanta.16 One day before the opening, the City Health Department conducted an inspection and said an ice machine which would cost $2,000 was required. Wolff, now out of funds, was able to convince the city that an ice machine was not needed, and Opening Day occurred as scheduled.17At that first game, 4,418 fans attended, just short of the capacity of 4,500. As the season progressed, the fans kept coming. Total attendance for 1980 was 175,963.18

A new opportunity arose in 1981. A friend called Wolff to let him know that a start-up baseball newspaper, The All American Baseball News, was for sale. The publisher and editor, Allan Simpson, a Canadian living in White Rock, British Columbia, was struggling. With most of his subscribers in the United States, he needed to print and mail the publication from across the border. Every two weeks he would have to drive over to make certain the publication was printed and distributed on time. As a one-man show, it was an impossible situation. He needed a visa to come to the States to survive.

Wolff liked what Simpson was producing and purchased the paper. He was able to procure a visa for Simpson, who moved with his family to Durham. The name of the newspaper was changed to Baseball America, and Wolff became the publisher. Simpson remained as editor. The staff of the Durham Bulls took over the duties of circulation, advertising, printing, and all the business aspects of running a newspaper. Simpson was able to concentrate on the editorial content. In the past, The Sporting News had been baseball’s newspaper, but it had pulled back on much of its baseball coverage. Within a few years Baseball America became the leading baseball publication.

With the Durham Bulls having had a successful start, Wolff turned his attention to three other minor league franchises. He bought a 50 percent stake in the Asheville Tourists, which were having financial difficulties. With his staff, the franchise became viable once again. Wolff sold his stake in 1985. Asheville was the beginning of his pattern of buying into minor league franchises that were having financial issues. Using sound management practices plus the Durham experience, he and his associates were able to successfully turn the franchises around.

The second was the Utica Blue Sox, whose owner, Van Schley, was one of the Durham investors. He requested help from Wolff. Interestingly, Roger Kahn — author of The Boys of Summer – was looking for a team to be the subject of a new book about minor league baseball. Wolff bought a stake in the Blue Sox and Kahn became president of the team. Once the franchise was on firmer footing, Wolff sold his interest in 1984.

Kahn did publish the book Good Enough to Dream about his season with Utica.19 Given his involvement with Wolff, he offered the following description, “Miles Wolff is courteous, businesslike and self-assured. When he discusses his success, he tends to do so in terms of its being no big deal. This may have less to do with modesty than with reserve. In conversation, he’s cerebral and dispassionate.”20

In 1982, Wolff became the owner of a third minor league team, the Pulaski Braves in the Appalachian League. In 1983 he married Michele Guimond. Michelle was from northern Maine and was a teacher for special needs kids in Butner, North Carolina. They had two children, Hoffman in 1984 and Claire in 1985. Hoffman graduated from Roanoke College and received his MBA from Laval University. He is married with one son and, on a part-time basis, handles some media tasks for the American Association. Daughter Claire has a master’s in social work from Washington University in St. Louis. She now teaches at the University of Missouri in St. Louis. Claire is also married with one son.

Wolff then turned his attention to the city of Burlington in Alamance County, North Carolina. Burlington, thirty miles west of Durham, had a rich tradition of baseball that began with teams that played in North Carolina’s textile leagues. In 1960 the City of Burlington bought a ballpark in Danville, Virginia, moved it to Burlington, and attracted a minor league team, the Alamance Indians. Unfortunately, minor league baseball had left Burlington in 1972.

Wolff convinced Burlington officials to upgrade the stadium as he pursued a franchise in the South Atlantic League. Unable to secure the franchise, he continued to pay rent to the city while pursuing other opportunities. He finally succeeded in getting a team in the Appy League and baseball came back to Burlington for the 1986 season. The franchise proved successful in attracting fans and won the Appy League title in 1987.

While all of this was occurring, the idea for a movie about minor league baseball was taking shape. When Wolff was seeking investors to finance the Durham Bulls, he was told that Thom Mount, a Durham native and a Hollywood producer for Universal Pictures, might be interested. Mount invested $5,000 in the Bulls. When he visited Durham, he told Wolff, “We’ll make a movie here someday.”21

While all of this was occurring, the idea for a movie about minor league baseball was taking shape. When Wolff was seeking investors to finance the Durham Bulls, he was told that Thom Mount, a Durham native and a Hollywood producer for Universal Pictures, might be interested. Mount invested $5,000 in the Bulls. When he visited Durham, he told Wolff, “We’ll make a movie here someday.”21

After a few years had passed, Wolff heard from Mount, who by then had formed his own independent production company. He told Wolff that there was a former minor league ballplayer by the name of Ron Shelton who had a script about the minors. He suggested that Wolff meet with Shelton about the possible movie. Shelton visited Durham and was sold on its ballpark for the location. While many movie studios passed on the script, Orion Pictures decided to finance the movie, which became Bull Durham. It had a $9,000,000 budget and starred Kevin Costner, Susan Sarandon, and Tim Robbins.

While the DAP was the main locale for the movie, other fields including Burlington’s were used. The rights to use these fields and the opposing team’s uniforms had to be secured. Another challenge was that North Carolina was experiencing an uncharacteristic fall cold spell during the shooting of the movie. A particular situation caused Wolff to wonder why he had ever become involved with the movie. Shelton wanted a large crowd in attendance for a particular game he was filming. Wolff asked his season ticket holders and others to attend, with the attraction being free hot dogs. With a large crowd in attendance on a fall day, the production crew decided it should be a night game and everyone was sent home.22 Wolff was not happy.

To the surprise of most, Bull Durham was a major hit with box office returns of $50.8 million. Critics loved it. Vincent Canby of the New York Times praised Shelton’s direction: “He demonstrates the sort of expert comic timing and control that allow him to get in and out of situations so quickly that they’re over before one has time to question them. Part of the fun in watching Bull Durham is in the awareness that a clearly seen vision is being realized. This is one first-rate debut.”23 It is now considered by many to be the best baseball movie of all time.

The success of the movie added to the success of the Durham Bulls. The snorting bull sign, built for the movie, became a permanent attraction. Almost all games were now sellouts and the sale of Bulls merchandise was soaring. However, the ballpark was showing its age. It was ill-equipped to handle 300,000 fans a year. Wolff felt Durham could revitalize its downtown by building a new stadium near the heart of the city. City officials seemed to agree. Wolff engaged the architects who had designed Camden Yards in Baltimore for the venture and a design resulted. However, a citizens’ group protested public funding for the project, stating that there were greater needs. The funding for the new stadium ended up as a county-wide referendum and was defeated. A disappointed Wolff was quoted, “Hard promises had been made by politicians that weren’t kept.”24

As a result of this disappointment, Wolff decided to sell the Bulls, stating, “I didn’t get into baseball to play politics.”25 He had an interested party in Capital Broadcasting and its CEO, Jim Goodmon. Capital bought the club; with Goodmon’s political clout and connections, it was able to get the necessary funding for the new stadium. The ballpark, which opened in 1995, is one of the best in minor league baseball.

In 1987 Wolff became the owner of another minor league team, the Butte Copper Kings in the Pioneer League. The Butte team was somewhat independent, meaning that it had no affiliation with a major league club. However, the roster did include players who were sent there by the Texas Rangers and Milwaukee Brewers.26 In 1988 Wolff sold his interests in both Pulaski and Butte. With these sales, Wolff was left with Baseball America and the Burlington Indians. What would be next? An associate, Blake Cullen, encouraged him to think about hockey. As a result, Wolff was able to secure a franchise in the East Coast Hockey League (ECHL) for the Raleigh IceCaps in 1991. They played their home games, often to capacity crowds, in the Dorton Arena at the Raleigh Fairgrounds. When Wolff realized that a new facility being built would not include the IceCaps but would be used to attempt to secure a team in the National Hockey League, he sold his interest in 1995. The Hartford Whalers moved to North Carolina in 1997, becoming the Carolina Hurricanes.

While involved with the IceCaps, Wolff was still focused on baseball. As a minor league owner, he realized the team’s performance on the field was mainly dictated by the major league club that owned the players. While the fans of a minor league team want to see a winning franchise, the emphasis of the major league club has always been on player development. As a result, it is not easy to sustain the interest of the fans if the major league clubs who control the players are not interested in winning.

Wolff had successfully owned minor league franchises in two cities that were good markets for baseball and had unused ballparks. He was convinced that there were other cities like Durham and Burlington. Would it be possible to form a league of such cities that would be independent and not affiliates? Until Branch Rickey created farm teams affiliated with the St. Louis Cardinals, minor league teams had been independent entities. However, once the other major league clubs realized that Rickey’s scheme was viable, they had followed suit.

By the early 1960s, there were no independent leagues. Occasionally, there would be an independent team that for a season or two would operate without a major league affiliate, but until the 1973-1977 Portland Mavericks in the Northwest League, all were money losers. 27 To reinforce such thinking, Wolff found himself in 1990 as part of a minor league executive committee negotiating the agreement between the major and minor leagues. The agreement was reached, but he grew frustrated from the process. He said, “I came out of that thinking these are people I don’t want to do business with. I came out of that wanting to do the Northern League.”28

Wolff was able to find owners to create the Northern League, consisting of Duluth, St. Paul, and Rochester in Minnesota; Sioux Falls, South Dakota; Sioux City, Iowa; and Thunder Bay, Ontario, Canada. It began play in 1993 with Wolff as the commissioner. The league was very successful — only the Rochester franchise struggled. In 1994 it was sold to interests in Winnipeg, Canada, and moved to that city.

Buoyed by the success of the Northern League, Wolff next became involved with the Northeast League, consisting of teams mainly in New York State. In 1998 he became the commissioner of the league. In 1999 the Northern League merged with the Northeast League, creating a Northern League – Central and a Northern League – East. The Northern League – Central included the Northern League franchises while the Northeast teams were the Northern League – East. Wolff was commissioner of both leagues.

In 1998, he had purchased the Bangor, Maine, team with the intent of moving it to Quebec City as part of the Northeast League. All of the teams in which Wolff had held a controlling interest except Durham had an associate handling the day-to-day operations. This was not the case for the Quebec Capitales, which began play in 1999. As a result, Wolff and his family moved to Canada. He was greatly aided in his dealings with the French-speaking Quebec community by his wife Michele, who spoke French fluently. Though his family moved back to North Carolina after a year, he continued owning and operating Quebec City until 2010. At its 25th anniversary in 2004, ESPN published a list of the 10 best owners in sports. Wolff was number eight.29 In 2012, he was inducted into Quebec’s Baseball Hall of Fame, the only inductee who came from outside the province.30

In 2002 Wolff resigned as commissioner of the Northern League to devote more attention to the Northeast League, which was once again a separate entity, and his interests in Quebec. The Northeast League came to an end in 2004 but several of the teams joined a new Can-Am League. The Northern League folded in 2005 and four of the teams joined the new American Association of Professional Baseball. Both the Can-Am League and American Association were headquartered in Durham with Wolff as their commissioner. In 2012 the two leagues had interleague play, which was discontinued in the 2015 season.

While involved with making independent baseball a reality, Wolff and Simpson were still publishing Baseball America. It put out the first edition of The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball in 1993. The book attempted to be a comprehensive list of minor leagues and cities. It included yearly standings for every league, along with playoff results, league leaders, attendance figures, managers, and league presidents.31 The second edition, published in 1997, expanded the amount of early information for the clubs. The third edition, published in 2007, included many 19th-century leagues and the more recent independent leagues.

In 2000 Wolff sold his interest in Baseball America. Simpson left in 2006. After several other ownership changes, Baseball America remains today, as its website proclaims, “the authority on the MLB Draft, MLB prospects, college baseball, high school baseball, and international free agents.”

In what might be his final baseball venture, Wolff became the owner of a new franchise in Ottawa, Canada, that began play in the Can-Am League in 2015. As in Quebec City, he took on the responsibility for the day-to-day operations. In 2019 Wolff relinquished control of the Ottawa team (which ceased operating after that year). He also stepped down as commissioner of both the Can-Am League and the American Association. As Wolff welcomed 2020, he was looking to develop a closer association with his remaining team, the Appy League’s Burlington Royals. He was also selected for the Appy League Hall of Fame in 2020. Unfortunately, major league baseball announced plans to contract minor league baseball after the 2020 season.32 This was followed by the cancellation of the 2020 minor league season due to COVID-19. Wolff had planned to drift off into the sunset with Burlington but found himself the team’s sole employee as his GM and assistant GM took new jobs in February 2020.33

Given such circumstances, he decided to sell Burlington Baseball Inc., the company that holds the lease for the stadium and the operations contract for the Burlington Royals. He offered to sell to his former general manager, Ryan Keur.34 Keur was president of the Daytona Tortugas in the Florida State League. After brief negotiations the deal was consummated in March 2020. While Wolff would remain as a consultant to the Burlington team and was still involved in attempts to publish the fourth edition of the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, his noteworthy career was ending. Miles Wolff was no longer visibly connected to the sport of baseball.

His departure did not go unnoticed. Complementing Dan Moushon’s comments was a quote from John Manuel, former editor-in-chief of Baseball America and now a scout with the Minnesota Twins, “This saddens me. I think he has as much a claim as anybody to making what modern minor league baseball has become. Without what he did with the Durham Bulls, I don’t think we have what there is today.”35

Last revised: August 5, 2021

Other notable quotes about Miles Wolff

“He always has been the backbone of the organization. Somebody solid and dependable and not fly by night.” – Thomas Phelps, colleague in Burlington (2020)36

“If there were more people in baseball like Miles Wolff, the game wouldn’t be in its current troubled state.” – Stefan Fatsis, in the acknowledgments for Wild and Outside, his 2009 history of the Northern League37

“Wolff proved that owning a minor league baseball team could be fun and profitable.” – Fred Hothenberg, Associated Press sportswriter (1981)38

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Miles Wolff for his support and timely responses to questions.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and checked for accuracy by members of SABR’s fact-checking team.

Photo credits: Courtesy of Hoffman Wolff and Miles Wolff.

Notes

1 Bob Sutton, “Wolff — Out at Home: Iconic baseball man credited with Burlington’s stability walks away,” Burlington Times News, March 4, 2020 (https://www.thetimesnews.com/story/sports/mlb/2020/03/04/wolff—out-at-home-iconic-baseball-man-credited-with-burlingtons-stability-walks-away/41785225/)

2 John Thorn, “Baseball’s 100 Most Important People,” MLBlogs, November 10, 2014 (https://ourgame.mlblogs.com/baseballs-100-most-important-people-dfd3189f96de)

3 Sutton, “Wolff — Out at Home.”

4 Staff Report, “Daily News Editor Wolff Dies At Age 92,” Greensboro Daily News, December 29, 1991 (https://greensboro.com/daily-news-editor-wolff-dies-at-age-92/article_347bc407-396a-5991-b262-035435cf06a7.html,)

5 Bob Godfrey, “Greensboro’s Miles Wolff-He Has Re-Shaped Baseball in Our Lifetime,” September 8, 2010 (http://bobspoint.blogspot.com/2010/09/greensboros-miles-wolff-he-has-re-shaped-baseball-in-our-lifetime)

6 Miles Wolff, Lunch at the 5 &10, (Chicago, Ivan R. Dee, Inc. Revised and Expanded Edition), 1990.

7 Miles Wolff, Lunch at the 5 & 10, Back Cover.

8 Miles Wolff, Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Miles_Wolff

9 Mark Cryan, Cradle of the Game Baseball and Ballparks in North Carolina, (Minneapolis, MN: August Publications}, 2008, 177.

10 Dale Keiger, “M.V.P. of the Minors,” John Hopkins Magazine, April 1994 (https:pages.jh.edu/jhumag/494web/wolff.htm)

11 Miles Wolff, Jr., Season of the Owl, (New York: Stein and Day) 1980.

12 Kieger, “M.V.P. of the Minors”

13 Kieger

14 Cryan, Cradle of the Game, 195.

15 Kieger, “M.V.P. of the Minors”

16 Cryan, Cradle of the Game, 196.

17 Interview with Miles Wolff, April 14, 2021.

18 Kieger, “M.V.P. of the Minors”

19 Roger Kahn, Good Enough to Dream. (New York: Doubleday, Inc.), 1985.

20 Kieger, “M.V.P. of the Minors”

21 Cryan, Cradle of the Game, 171.

22 Cryan, Cradle of the Game,172.

23 Vincent Canby, “FILMVIEW; Toons and Bushers Fly High,” New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/1988/07/03/movies/film-view-toons-and-bushers-fly-high.html, July 3, 1988.

24 Keiger, “M.V.P. of the Minors”.

25 Keiger,

26 Butte Copper Kings, Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Butte_Copper_Kings

27 Larry Stone, “Meet the nuttiest team the Northwest has ever seen,” Seattle Times, https://www.seattletimes.com/sports/meet-the-nuttiest-baseball-team-the-northwest-has-ever-seen/, July 26, 2014.

28 Dale Keiger, M.V.P. of the Minors.

29 Charles Hirshberg, ESPN25, (New York: Hyperion Publishing) 2004, 107-11.

30 “Wolff To Be Inducted Into Quebec Baseball Hall of Fame,” Ballpark Business, November 1, 2012 (https://ballparkbiz.wordpress.com/2012/11/01/wolff-to-be-inducted-into-quebec-baseball-hall-of-fame/)

31 W. Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, NC: Baseball America) 1993.

32 BA Staff, “All 42 Teams Reportedly Up For Elimination in MLB’s Minor League Reduction Proposal,” Baseball America, November 29, 2019.

33 J.J. Cooper, “Miles Wolff, ‘Icon Of The Baseball Industry,’ Sells Burlington Royals,” Baseball America, March 6, 2020.

34 Zach Spedden, “Miles Wolff Sales of Burlington Baseball Inc. Marks End of Era,” Ballpark Digest, March 5, 2020. (https://ballparkdigest.com/2020/03/05/miles-wolffs-sale-of-burlington-baseball-inc-marks-end-of-era)

35 Sutton, “Wolff — Out at Home.”

36 Sutton,

37 Stefan Fatsis, Wild and Outside: How a Renegade Minor League Revived the Spirit of Baseball in America’s Heartland (New York: Walker & Company: 2009), 293.

38 “Wolff Brings Class to Minor Leagues” was the headline used by the Asheville (North Carolina) Citizen-Times in its version of the syndicated story that ran on April 19, 1981.

Full Name

Miles Wolff

Born

December 30, 1943 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.