Milt Pappas

Milt Pappas thought he deserved to be in the Hall of Fame. Wasn’t his won-lost record practically identical to Don Drysdale’s — even a bit better? Wasn’t Drysdale elected?

Milt Pappas thought he deserved to be in the Hall of Fame. Wasn’t his won-lost record practically identical to Don Drysdale’s — even a bit better? Wasn’t Drysdale elected?

Pappas was an outstanding pitcher for a long time; his closest comps include Orel Hershiser and Catfish Hunter as well as Drysdale.1 But he is remembered as the man who was traded for a superstar in one of the game’s most infamous deals.

Pappas’s conflicts and controversies threatened to overshadow his performance. He acknowledged his reputation as a clubhouse lawyer — a troublemaker — who carried an attitude of “always being right and everyone else was wrong.”2 A man of a thousand grievances, he alienated many teammates as well as management.

Milton Stephen Pappas was born in Detroit on April 11, 1939, the middle of three sons of Greek immigrants Steve and Eva Pappas. His parents’ birth names, Stedious Papastedgios and Eudoxia Misiakoulis, had been anglicized by immigration clerks at Ellis Island. Steve Pappas owned a neighborhood grocery store in the Greek section of Detroit, and the family spoke Greek at home. Youngest son Perry pitched in the Yankees’ farm system for three years.

The teenage Milt starred for Cooley High and in American Legion ball as a hard-throwing right-handed pitcher and slugging first baseman. The Detroit Tigers invited him to work out at Briggs Stadium while at least a dozen other teams also scouted him. The most persistent was Baltimore’s Lou D’Annunzio, who shadowed him all through high school, gave him pitching tips, and got to know his parents.

When Milt graduated in 1957, he had grown to 6-feet-3 and around 190 pounds. The scouts told him no team would offer him a bonus above $4,000 because anything more would mean he’d have to spend two years on a big-league bench as a bonus baby. In that case, Milt said, he wanted a major-league contract. The Tigers wouldn’t go along, but Baltimore scouts D’Annunzio and former Detroit pitching star Hal Newhouser said yes. The Tigers, who thought they had the inside track with the hometown boy, suspected he must have gotten more money under the table. Pappas said he didn’t.

Newhouser bought the prospect some new clothes and flew with him to Baltimore. Manager Paul Richards, who had scouted him personally, put the 18-year-old to work pitching batting practice. “Three or four days after I got there, he asked me if my arm was sore and I said no,” Pappas recalled. “Then he repeatedly asked me the question, and finally he said, ‘You know, isn’t your arm sore?’ I was eighteen; what the hell did I know? I finally said, ‘Oh, yeah, my arm’s sore.’”3

Richards put him on the disabled list, but he continued to throw batting practice. When the Tigers saw him on the mound, they protested. The commissioner’s office ordered the Orioles to restore him to the active roster.

The other Orioles resented teenagers Pappas and Jerry Walker for taking up roster spots in place of useful pitchers. Pappas said nobody would speak to him except the Cuban shortstop, Willy Miranda. He retaliated by pitching his teammates high and tight in batting practice.

Pappas made his debut against the Yankees on August 10. The first batters he faced were future Hall of Famers Enos Slaughter, Mickey Mantle, and Yogi Berra. Mantle singled, but he retired the other two. Working the eighth and ninth innings, he allowed two hits and no runs. Soon afterward Richards caught him out after curfew and sent him to Class-A Knoxville for two weeks, his only taste of the minors. Back in Baltimore in September, he finished the year with four relief appearances, allowing one run in nine innings.

The logical next step would have been down to the minors in 1958, but Pappas pitched his way onto the Orioles’ roster. “Nobody has really hit him hard all spring,” Richards said, “and with that fast ball he has he just might get by anywhere.” Teammate Billy Loes taught the youngster a curve, but it was still a work in progress.4

Going straight from high school to the majors, Pappas became a regular starter at 19 and was the first pitcher known to be put on a strict pitch count. Richards, a former catcher who had made his reputation by developing Newhouser into a two-time MVP, believed in protecting young arms. “No matter what inning it was, what the count was, what the score was, or what was going on, when I got to eighty pitches, he pulled me,” Pappas said. He thought the delicate treatment added several years to his career.5

He didn’t complete a game until his 13th appearance on June 6, when he beat the Kansas City A’s while throwing 82 pitches. Richards kept him on a short leash for more than half the season. Then on July 24 the Orioles took a 7-2 lead over the White Sox, and Richards left Pappas in to finish a sloppy complete game with six walks and 137 pitches.

Pappas turned in a mediocre 4.06 ERA and a 10-10 record for the sixth-place club. In 1959 all restrictions were off. At 20 years old, he worked 209⅓ innings, completed 15 of 27 starts, second most in the American League, and chalked up a 15-9 record and 3.27 ERA. While the Orioles’ weak hitting consigned them to another sixth-place finish, Pappas was a rising star. After the season he married his high school girlfriend, Carole Tragg.

Richards had been stockpiling young arms, believing that pitching was the foundation of a winning team. In 1960 he threw five of them into the fire. Pappas, Jerry Walker, and “Fat Jack” Fisher were 21, Chuck Estrada and Steve Barber, 22. The “Kiddie Korps,” backed by veterans Hoyt Wilhelm and Skinny Brown, nearly pitched Baltimore to a pennant.

“Everyone wonders where the kids get all their confidence,” Richards said. “You’d have confidence too if you knew you could throw hell out of the ball.”6 Teammate Jackie Brandt said, “Barber threw a shot put [a heavy sinking fastball]. Estrada threw the hardest. Pappas was slider, slider, slider. Fisher’s fastball wasn’t too much, but he had a grinding curveball. Walker tricked you.”7

With an infield that included rookies Jim Gentile at first, Marv Breeding at second, Ron Hansen at short, and 23-year-old “veteran” Brooks Robinson at third, the Baby Birds jockeyed for first place all summer with the Yankees and defending champion White Sox. New York came to Baltimore on September 2 with a one-game lead. The Yanks led with their ace, Whitey Ford, who had already shut out the Orioles three times. Pappas countered with a three-hit shutout of his own to lift Baltimore into a tie at the top of the standings. Fisher spun another shutout the next day, and Estrada and Wilhelm combined to finish a sweep that put the Orioles ahead by two games.

Baltimore’s pennant bubble popped two weeks later when New York beat them in four straight at Yankee Stadium. Pappas held the Bronx Bombers to five hits in the finale, but lost, 2-0, when his teammates managed only two singles off Ralph Terry. The Yankees went on to win 15 in a row and claim the pennant, as usual.

The Orioles finished second, eight games back. It was their first winning season since the St. Louis Browns moved to Baltimore six years earlier and a turning point for the franchise. They allowed the fewest runs in the league as the kiddies all recorded better-than-average ERAs. Estrada led the way with an 18-11 mark and 3.58 ERA; Pappas went 15-11, 3.37.

The club had an even better year in 1961, improving from 89 victories to 95, but dropped to third place and never came close to the high-flying Yankees and Tigers despite the best pitching and defense in the AL. Barber compiled 18 wins and Estrada 15. Pappas lowered his ERA to 3.04 with a 13-9 record.

After a disappointing 1962, the Orioles resumed their futile chase of the Yankees, always a contender but never a champion. Barber and Pappas emerged as the top pitchers; Estrada fell victim to a sore arm, and Walker and Fisher were traded.

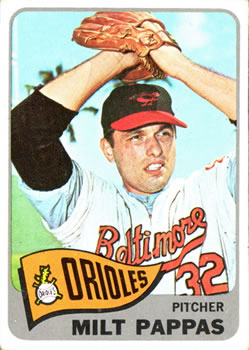

Pappas started the 1965 All-Star Game, although he was ripped for three runs in his only inning. After eight full seasons, still only 26, he had won 110 games and established himself as one of the league’s best pitchers. He gave the Orioles 200-plus innings a year with an adjusted ERA of 113 (100 is average). Never overpowering, he became a premier control pitcher.

But some of his bosses thought he should have done better. Hank Bauer, who took over as manager in 1964, said, “Pappas would go five innings and start looking at the bullpen.”8 It’s a curious remark, since Pappas led the Orioles in complete games for both his years under Bauer, but the knock stuck with him for the rest of his career: that he wanted relief as soon as he was assured of a victory and was content to win 12 to 15 games. “That’s all he wanted to win,” teammate Boog Powell recalled. “I don’t know why.”9

Pappas heard his name mentioned in trade speculation after the 1965 season. That alarmed him, because he and Carole and their children, Steven and Michelle, made their home in Baltimore year-round, and he was about to open a restaurant. “Bauer and general manager Lee] MacPhail had assured me I wasn’t going anywhere,” he said later.10

Steve Barber, who was discontented, had asked to be traded. But when MacPhail began talking to the Cincinnati Reds about their slugger Frank Robinson, the Reds, who already had two left-handed starters, insisted on Pappas instead of Barber.

The Cincinnati Enquirer announced the deal with a headline spread across the top of page 1 screaming that “superstar Frank Robinson” was gone to Baltimore. The Baltimore Sun crowed, “Officials Here Are Jubilant” over the acquisition of “one of major-league baseball’s great stars.”11

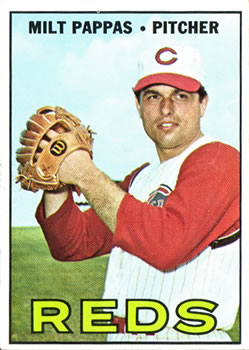

Adding to Pappas’s shock, the Reds sent him a contract calling for the same salary he had earned the previous year. Though he settled for a small raise, the incident left a sour taste and set the tone for his time in Cincinnati. Local fans, outraged by their loss, booed him every time he walked to the mound. “I hated every minute I was there,” Pappas said.12 He finished his first Cincinnati season at 12-11 with a career-worst 4.29 ERA. It didn’t help that the Reds fell to seventh place with their first losing record in six years.

Adding to Pappas’s shock, the Reds sent him a contract calling for the same salary he had earned the previous year. Though he settled for a small raise, the incident left a sour taste and set the tone for his time in Cincinnati. Local fans, outraged by their loss, booed him every time he walked to the mound. “I hated every minute I was there,” Pappas said.12 He finished his first Cincinnati season at 12-11 with a career-worst 4.29 ERA. It didn’t help that the Reds fell to seventh place with their first losing record in six years.

While several other players were included in the swap, Pappas for Robinson is enshrined in history as one of baseball’s most lopsided trades. Robinson won the Triple Crown and the MVP Award in 1966, leading the Orioles to their first pennant and World Series championship. When Pappas went home to Baltimore at the end of the season, some O’s fans thanked him for making it possible.13

Pappas’s Baltimore teammates had elected him their player representative, and he took on the same job in Cincinnati. The powerless reps could only complain about leaky clubhouse showers and seedy hotel rooms, but that changed when the Players Association hired Marvin Miller as executive director in 1966. Under the first collective bargaining agreement with owners, players gained the right to a formal grievance procedure, although the owners’ commissioner was the final arbiter.

One of the first tests of the new arrangement came early in 1968, when Reds players saw sportswriters and coaches flying in first-class seats while players were in coach. The union contract guaranteed that players would go first class. Miller and Pappas went to the office of general manager Bob Howsam to discuss the issue and found themselves confronted by angry writers. “Howsam had invited them to a grievance meeting!” Miller exclaimed.14 The players got their first-class seats along with a roasting from the press over their alleged demand for special treatment.

A few weeks later the assassination of Senator Robert Kennedy put Pappas in management’s cross-hairs again and also put him at odds with many teammates. Commissioner William Eckert ordered that the games of June 8 could not start until after Kennedy was buried. When the burial was delayed into the night, the Reds voted not to play, but manager Dave Bristol and club executives persuaded — or intimidated — them to reconsider. As the team took the field, Pappas shouted, “You’re wrong, wrong. I’m telling you, you’re wrong. If you go, get yourself another player rep.”15 The Reds got themselves another pitcher. They traded Pappas to Atlanta three days later.

The six-player deal revived Pappas’s career; he was the Braves’ best pitcher for the rest of the season, reeling off 21 consecutive scoreless innings on the way to a team-leading 2.37 ERA and a 10-8 mark.

In the first year of division play in 1969, a September surge lifted the Braves to the National League West title, but Pappas was no help. Back problems sidelined him for most of July, and he was demoted to the bullpen. In his only postseason appearance, he relieved in Game Two of the National League Championship Series against the Mets with Atlanta already trailing, 6-0. Pappas sloshed fuel on the fire, giving up three runs in 2⅓ innings.

The next spring found him back in the bullpen and practically forgotten. Atlanta sold him to the Chicago Cubs in June for a reported $30,000. The Cubs’ traveling secretary, Blake Cullen, arranged the deal. He and Pappas had become friends after they were introduced by a mutual friend, singer Jerry Vale. Cullen convinced the front office that the 31-year-old was not washed up.

But his reputation traveled with him: “a ‘clubhouse lawyer,’ a guy who supposedly causes trouble,” as Chicago writer Jerome Holtzman put it. “I’ve heard the rumors about him,” manager Leo Durocher said. “But to me they’re just rumors. I don’t believe in rumors.” Pappas said the label followed anyone “who does a half decent job” as a player representative.16

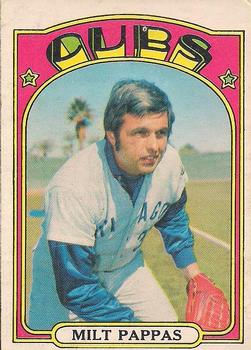

Pappas made his friend Cullen look like a genius when he won his first four starts for Chicago, including three straight complete games. He said he couldn’t remember the last time he finished three in a row. Durocher, the very definition of old school, believed in letting his starters go the distance, and Pappas proved that he was not just a five-inning pitcher.

Finishing 10-8, 2.68 after the sale, Pappas gave the Cubs one of the majors’ strongest starting quartets along with Ferguson Jenkins, Bill Hands, and Ken Holtzman. In 1971 he won a career-high 17 games, against 14 defeats, and tied for the league lead with five shutouts. He worked 261⅓ innings, completing 14 of 35 starts. On September 24 he pitched a rare immaculate inning against Philadelphia, striking out the side on nine pitches.

The next year was even better, although the 1972 season started badly — and late. Opening Day was delayed for 10 days by the first players strike. Pappas was one of the vocal leaders in the walkout over owner contributions to the players’ pension fund. With a short spring training, he came down with a sore arm, and his record stood at 6-7 at the end of July. Discouraged, he considered retiring but continued to pitch.

Beginning August 2, he won his last 11 consecutive starts, winding up at 17-7 with a 2.77 ERA, 10th best in the league, and the NL’s lowest walk rate. He finished ninth in balloting for the Cy Young Award, the only time he got any votes. It was the best season of his career.

He pitched the game of his life on September 2 when he retired the first 26 San Diego Padres in a row. He ran the count to 3-and-2 against pinch-hitter Larry Stahl, one strike away from a perfect game. The next slider slid just a bit outside, according to plate umpire Bruce Froemming, and Stahl took his base. “I went crazy,” Pappas remembered. “I called Bruce Froemming every name you can think of. I knew he didn’t have the guts to throw me out, because I still had the no-hitter.”17 His only no-hitter turned into yet another of his many grievances.

He pitched the game of his life on September 2 when he retired the first 26 San Diego Padres in a row. He ran the count to 3-and-2 against pinch-hitter Larry Stahl, one strike away from a perfect game. The next slider slid just a bit outside, according to plate umpire Bruce Froemming, and Stahl took his base. “I went crazy,” Pappas remembered. “I called Bruce Froemming every name you can think of. I knew he didn’t have the guts to throw me out, because I still had the no-hitter.”17 His only no-hitter turned into yet another of his many grievances.

He was still steaming 35 years later. “I still to this day don’t understand what Bruce Froemming was going through in his mind at that time,” he told ESPN in 2007. “Why didn’t he throw up that right hand like the umpire did in the perfect game with Don Larsen?” He added, “It’s a home game in Wrigley Field. I’m pitching for the Chicago Cubs. The score is 8-0 in favor of the Cubs. What does he have to lose by not calling the last pitch a strike to call a perfect game?”18

Pappas won his 200th game in September with his mother and brother Perry in the stands. He became the first to reach the milestone without ever winning 20 in a season. That was his last highlight. In 1973 he went sharply downhill in every category, with his strikeouts dropping to less than three per nine innings.

The Cubs signed him to another one-year contract, but near the end of spring training in 1974, manager Whitey Lockman called him in for the dreaded conversation. He was released shortly before Opening Day. At 35, he said, “I felt I still had a few good years left in me. Why Whitey Lockman did that to me, to this day I still don’t know. That’s not the way a career should end.”19

Pappas had worked as an offseason sports reporter for WLS-TV in Chicago and had had his teeth capped in preparation for a broadcasting career, but the station told him it had no openings. He managed a team in the short-lived American Slo-Pitch Softball League, coached baseball for three years at North Central College in Illinois, and sold liquor and gyro sandwiches before he found his niche as sales manager of a nail and screw distributor, a job he held until retirement.

Late in Pappas’s baseball career, Carole had become an alcoholic. Milt believed her heavy drinking may have started when she discovered that he had a girlfriend in Atlanta. She joined Alcoholics Anonymous, but was never able to stop drinking for good. Steven and Michelle covered for her. When Milt called home from the road, they would tell him that their mother was out, but she was actually passed out.

On September 11, 1982, Carole left for a hair appointment and shopping. She never came home. When Milt reported her missing, police at first assumed she had run away, but she and Milt had been preparing to welcome their son and his bride back from their honeymoon that night, and she had left a recipe for Steve’s favorite yogurt cake on the kitchen counter.

When the police did begin an investigation, Carole’s hair stylist and a store clerk said she had seemed disoriented. Her history of alcoholism gave detectives another reason to doubt that she was a crime victim. In addition, she was taking codeine for pain after gum surgery.

Naturally, the husband was a suspect, but Milt said he was cleared by a polygraph exam. He believed that his wife had been kidnapped and murdered. As the investigation stalled, he went on with his life. Less than a year later he was living with a new girlfriend, Judi Bloome, and they had a daughter together.20

Nearly five years after Carole disappeared, workers draining a pond near the Pappas home uncovered her car with her body inside. The coroner ruled her death accidental on the theory that she had become confused under the influence of the pain pills, made a wrong turn, and driven into the pond. There was still mystery: The car’s ignition was turned off and the gearshift was in Park.21

Milt and Judi married, and he lived to be 76 before he died on April 19, 2016, still convinced that he had been cheated out of his rightful place in the Hall of Fame.

When he became eligible for the Hall in 1979, the screening committee of the Baseball Writers Association initially left him off the ballot. “What are they doing to me?” he protested. “I won 209 games.” The Chicago Tribune’s Jerome Holtzman persuaded the committee to add Pappas’s name, but he received only 5 votes out of 432 and was dropped from the ballot in future years.22 To twist the knife, the writers elected 209-game winner Don Drysdale in 1984.

Pappas’s won-lost record was 209-164, Drysdale’s 209-166. The resemblance ends there. Drysdale won a Cy Young Award; Pappas never came close. Drysdale was an eight-time All-Star; Pappas made the team twice. Drysdale held the record for pitching 58 consecutive shutout innings; Pappas never led his league in any significant category.

Jay Jaffe’s JAWS system for evaluating Hall of Famers ranks Drysdale 51st among all starting pitchers in history, Pappas 186th as of 2019. “It’s just absurd to compare them,” analyst Bill James wrote.23 But Pappas went to his grave believing that he had been blackballed because he was an outspoken union activist who didn’t cozy up to sportswriters.

- Related link: Listen to the SABR Oral History interview with Milt Pappas on August 28, 1992, by Gabriel Schechter at oralhistory.sabr.org

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Notes

1 According to Bill James’s Similarity Scores at baseball-reference.com.

2 Milt Pappas with Wayne Mausser and Larry Names, Out at Home (Oshkosh, Wisconsin: LKP Group, 2000), viii.

3 John Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards: An Oral History of the Baltimore Orioles (New York: Contemporary, 2001), 51.

4 Bob Maisel, “Milt Pappas Gains Berth,” Baltimore Sun, April 3, 1958: S15.

5 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street, 78.

6 “Young Orioles,” Time, June 6, 1960, online archive.

7 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street, 98.

8 Eisenberg, “How the Magic Began,” Baltimore Sun, July 13, 1986: 1C.

9 Eisenberg, From 33rd Street, 129.

10 Ibid., 150.

11 Lou Smith, “Reds Trade Off Frank Robinson,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 10, 1965: 1; Jim Elliott, “Orioles Get Frank Robinson From Cincinnati Reds,” Baltimore Sun, December 10, 1965: C1.

12 Pappas interview by Gabriel Schechter, August 28, 1992. SABR Oral History Collection.

13 Pappas, Out at Home, 178.

14 Marvin Miller, A Whole Different Ball Game (New York: Birch Lane, 1991), 164.

15 Bill Ford, “Walkout Is Averted, But Pappas ‘Quits’,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 9, 1968: 1-D.

16 Jerome Holtzman, “Meet Mr. Pappas, the Cubs’ New Ace,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1970: 14.

17 David Schoenfield, “Milt Pappas remembered for Frank Robinson trade and near-perfect game,” espn.com, April 19, 2016.

18 Bruce Weber, “Milt Pappas, Cagey All-Star Traded for Hall of Famer, Dies at 76,” New York Times, April 19, 2016: B15.

19 Fred Mitchell, “When the cheering stops,” Chicago Tribune, August 31, 1986: C4.

20 Pappas, Out at Home, 322-333.

21 Associated Press, “Car of Pappas’ wife, body discovered 5 years later,” Baltimore Sun, August 8, 1987: 2B; Joseph Sjostrom, “Death ruled accidental in Pappas case,” Chicago Tribune, October 9, 1987: A1.

22 Holtzman, “Hall of Fame just a popularity contest,” Chicago Tribune, January 6, 1985: E6.

23 Bill James, The Politics of Glory (New York: Macmillan, 1994), 394.

Full Name

Milton Stephen Pappas

Born

May 11, 1939 at Detroit, MI (USA)

Died

April 19, 2016 at Beecher, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.