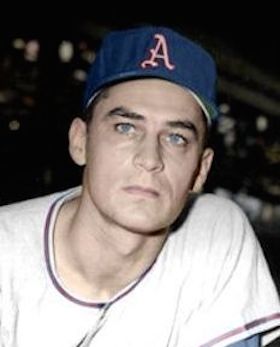

Moe Burtschy

Arguably one of the slowest runners in baseball, Edward Frank Burtschy earned the nickname “Molasses Shoe,” or “Moe” for short. The bulky 6’3”, 208-pound hurler may have tarried on the base path but the hard throwing righty, in the vernacular, could bring it. The problem was where. Blessed with a blazing fastball and cursed that he could not control it, Burtschy had a five-year major league career featuring walks and wild pitches as a staple.

Arguably one of the slowest runners in baseball, Edward Frank Burtschy earned the nickname “Molasses Shoe,” or “Moe” for short. The bulky 6’3”, 208-pound hurler may have tarried on the base path but the hard throwing righty, in the vernacular, could bring it. The problem was where. Blessed with a blazing fastball and cursed that he could not control it, Burtschy had a five-year major league career featuring walks and wild pitches as a staple.

Burtschy was born on April 18, 1922, the eldest of three children (and the only son) of Edward William and Margaret E. (Miller) Burtschy, in Cincinnati, Ohio. He was the great-grandson of a German immigrant who settled in Ohio in the 19th century. In 1917 Edward’s father, Edward William Burtschy, went to Europe during World War I as part of the American Expeditionary Force. When he returned, Edward found long-term employment as a clerk with the railroad.

Burtschy attended Roger Bacon High School in Cincinnati, a Franciscan school established in 1928. He lettered in football, basketball, and especially baseball where his prowess attracted major league scouts. In 1941, a year removed from his high school graduation, Burtschy signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers. It appears he captured the attention of Dayton, Ohio, native Ducky Holmes who had a cup of coffee in the National League as a catcher in 1906. Variously serving as a scout and minor league manager after his playing career, in 1941 Holmes was the skipper of the Dayton Ducks in the Middle Atlantic League (Class C). Burtschy received a one game trial with the Ducks before demotion to the Ashland (Kentucky) Colonels in the Mountain State League. Despite walking nearly five batters per nine innings, Burtschy successfully prevented runners from scoring as he led the Class D circuit in ERA (2.46).

In 1942 Burtschy inexplicably pitched in the Cincinnati organization.1 Scouted and likely signed by former minor league outfielder Eddie Ries, Burtschy was advanced to the Columbia (South Carolina) Reds in the South Atlantic League (Class B). Control problems persisted: in 192 innings he fashioned 14 wild pitches and 15 hit batters and finished the bruising season with a middling record of 9-9, 3.47. What the Reds intended to do with Burtschy thereafter remains a mystery; the decision was taken out of their hands when Burtschy enlisted in the US Navy in 1943.

Burtschy spent three years in the service during World War II, most of it in the Pacific Theatre on the USS Ticonderoga following the Essex-class aircraft carrier’s commissioning in May 1944. Burtschy was on board on January 21, 1945, when a Japanese kamikaze attacked the carrier’s starboard side, killing or injuring 100 sailors. Burtschy was likely spared by being in the wrong place at the right time. The plane struck where he would normally have been at that time of day. Prompt repairs had the Ticonderoga back in full service by April. Four months later she participated in the attacks on Tokyo just before the Japanese surrender.2

When the war ended Burtschy returned stateside to resume his playing career. In 1946 an inauspicious resumption in the South Atlantic League (Class A) led to the righty’s rapid bounce from the Reds to the Pittsburgh Pirates in an unknown transaction. Assigned to the Anniston (Alabama) Rams in the Southeastern League (Class B), Burtschy’s initial success (seven wins in his first 10 decisions) placed him among the league leaders before he lost four straight decisions. By 1947 he was assigned to yet another organization: the Philadelphia Athletics.

It is unclear why Pittsburgh parted with Burtschy, but one can generally assume why the once-proud Athletics acquired the right-hander. For 11 of the preceding 12 years the club had finished last or next-to-last in the American League standings. With a woeful pitching staff contributing substantially to this poor showing, manager-owner Connie Mack appears to have been exploring pitchers of every hue: Burtschy was but one of six hurlers the A’s acquired during the offseason to bolster their pitching. Unfortunately, Burtschy’s 1947 contributions were less than encouraging: bouncing among three affiliates, he posted a record of 5-7, with a 6.47 ERA in 121 innings.

In 1948-49, however, he rebounded to construct two of the finest back-to-back campaigns of his career. Assigned to the South Atlantic League with the Savannah (Georgia) Indians—where he spent a small portion of the 1947 season—Burtschy toiled a league leading (and career high) 252 innings in 1948 and another 204 in 1949 (when a brief promotion to Class AAA Buffalo garnered an additional inning of work). Despite a high yield of walks, hit batters, and wild pitches, the durable righty fashioned a 3.49 ERA in 456 innings with the Indians over the two-year period and placed among the 1948 Class A circuit leaders with 16 wins.

In 1950, following three promising seasons, the Athletics collapsed to 102 losses, the result of a major league worst staff 5.49 ERA. After the demotion of rookie Harry Byrd and the June 5 release of veteran hurlers Ed Klieman and Phil Marchildon, Hall of Fame skipper Connie Mack beckoned Burtschy to join the parent club. At the time the 28-year-old was working primarily in relief for the Buffalo Bisons in the International League. On June 17, 1950, Burtschy made his major league debut in Cleveland. Entering the sixth inning trailing 6-5, the hurler walked the only batter he faced (Indians’ left fielder Dale Mitchell). The next day Burtschy served mop-up in a 21-2 loss. Despite two wild pitches and seven walks he held the opposition scoreless for four innings before the Indians touched him for three runs (two earned) in the eighth. On June 29, in his fourth relief appearance, Burtschy surrendered a seventh-inning two-run homer to slugger Ted Williams in the midst of the Athletics’ 22-14 slugfest loss to the Boston Red Sox. He pitched 9 1/3 innings of scoreless relief thereafter to earn his only, and utterly forgettable, major league starting assignment. On August 1 Burtschy was matched against the White Sox in Chicago’s Comiskey Park. In his 2 1/3 innings as a starter he yielded six runs on seven hits and two walks to absorb his first major league loss. Burtschy finished his debut campaign with a 7.11 ERA in 19 innings (nine appearances; 2.263 WHIP).

The following spring he reported to training camp and was soon involved in one of the most unique exhibitions in grapefruit league history. In a game against the Boston Braves in Bradenton, Florida, on March 24, 1951, Burtschy was one of 18 Athletics players and coaches ejected by NL umpire Frank Dascoli for bench-jockeying a disputed call from the day before. When the regular season began Burtschy was used sparingly until a string of success (one unearned run in 8⅔ innings) garnered the confidence of Jimmy Dykes, the Athletics’ new manager. But Burtschy’s opportunity for continued use closed when searing elbow pain in June forced him to the bench. A month later his season was completely shut down after surgery at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore for removal of bone chips. Three years would pass before he threw his next major league pitch.

In the spring of 1952 his fellow-hurlers noted Burtschy’s advanced conditioning. A regimen of post-surgery “exercises all winter to overcome the effects of a mid-summer operation” had enabled him to pitch “with fluid ease and motion.”3 Burtschy’s three innings of no-hit relief against the Washington Senators in a March exhibition seemingly bolstered his shot at an Athletics roster spot. But the February 12 purchase of veteran righty Ed Wright from the New York Giants appears to have determined Burtschy’s fate. Though he broke camp with the team Burtschy did not make an appearance. On May 6, three days after the waiver acquisition of utility infielder Hal Bevan from the Boston Red Sox, Burtschy became the odd man out and got cut.4 He was assigned to the Ottawa (Ontario) A’s in the International League where he had a middling campaign: 3-5, 4.45 ERA in 93 innings, mostly in relief.

In 1953, much as he did five years earlier, Burtschy rebounded nicely. Working exclusively in relief during the first two months of the season, he collected four wins in 20 appearances (including a controversial April 30 win over the Syracuse Chiefs in which a victory awarded to teammate Jim Bell was overruled by the league and given to Burtschy). In August, as the wins continued to accrue, Burtschy found himself among the circuit leaders with 12 victories. Though he failed in his last three decisions, this did not detract from his fine season: Ottawa’s “ace relief pitcher”5 placed among the league leaders with 50 appearances and a 2.82 ERA. At the end of the season, the big club recalled Burtschy, but he did not make an appearance. “[T]his is a new Burtschy,” said Athletics’ farm director Bernie Guest. “He looked good when he was up before, but had a lot of trouble with his arm. His record at Ottawa . . . certainly would indicate that the operation he underwent for the removal of the bone chips from his right elbow was a success. He won 12 and lost seven, but that’s not the point. The fact that he got into 50 games proves his arm must be okay now.”6

Philadelphia was spared a league worst ERA in 1953 by an even more feeble Detroit Tigers’ staff. In 1954, Burtschy was one of 13 rookie hurlers invited to spring training. He made his season debut on his 32nd birthday and held Boston to two hits in four scoreless innings before yielding a 13th inning walk-off homer to Red Sox centerfielder Jackie Jensen. Burtschy did not surrender an earned run over the next six innings, driving his ERA below 1.00, before walks foiled his attempt to protect a 6-3 lead against the Baltimore Orioles on May 10. Three days later he earned his first major league win with two innings of no-hit relief against the Chicago White Sox. But future Hall of Famer Al Kaline ruined his next outing. On May 19 the Tigers’ outfielder stroked a walk-off single against Burtschy on the righty’s first pitch of the game. And adding insult to injury, three weeks later the slugger collected his first major league grand slam off Burtschy in a 16-5 Athletics loss. These setbacks did not preclude A’s player-manager Eddie Joost from turning frequently to Burtschy, who placed among the American League leaders with 46 appearances. Less notably, he also placed among the leaders in hit batters (8) and wild pitches (7) in just 94⅔ innings. On June 26 one wild pitch proved costly in Baltimore, allowing the winning run to score in another walk-off loss. Excepting a miserable outing against the New York Yankees on September 19 Burtschy surrendered just two runs and eight hits over his final 19 innings (11 appearances), finishing the campaign with a respectable record of 5-4, and a 3.80 ERA. Seeking to build upon this success, Burtschy travelled south to play winter ball in the Veracruz League.

But success was not in Burtschy’s immediate future. In 1955, the Athletics, amidst grand expectations in their new Kansas City environs, set off on the wrong foot with a pair of five-game losing streaks through May 10. In a roster shakeup the next day, the club purchased or traded for four players. To make room on the roster the A’s optioned three pitchers including Burtschy. Despite two wins Burtschy had struggled to keep his ERA below 10.00, surrendering 17 hits, 10 walks and 13 runs in 11 1/3 innings. Though initially assigned to the Columbus (Ohio) Jets in the International League, Burtschy did not play with them, finishing the season with the Portland Beavers in the Pacific Coast League. Whatever problems plagued him in Philadelphia were quickly solved. Burtschy, who appeared in 29 games, mostly in relief, built a solid record: going 6-8, 3.02 in 83 1/3 innings. Portland manager Clay Hopper “rated [Burtschy] one of the [league’s] best hurlers.”7 In March 1956, Kansas City Athletics’ skipper Lou Boudreau endorsed this assessment when he anointed Burtschy among his key middle relievers for the season.

When the 1956 season began the 34-year-old hurler appeared poised to capture the success that had eluded him in years past. After opening with nine innings of three-hit scoreless relief, Burtschy’s record on May 20 stood at 2-0, 1.57 in 12 appearances. He had come “to the forefront among the relievers,” reported The Sporting News. “[A]s of now [he] is the No. 1 artist in the [Athletics’] bull pen.”8 But continued success proved elusive. On May 26, Burtschy gave up eight earned runs and 12 hits to the Tigers in six innings of relief. Three days later he yielded three runs (one earned) to the White Sox in 2 1/3 innings. Although he didn’t give up a hit, he managed to walk five guys. Burtschy seemed poised to recapture some earlier success pitching 6⅔ innings of scoreless relief before being traded to the New York Yankees on June 14. The Bronx Bombers shipped him immediately to the Richmond Virginians in the International League, and Burtschy never resurfaced in the major leagues. In 1956 and 1957 he made 65 appearances among three Class AAA clubs. In 1958 Burtschy unsuccessfully tried to latch on with the Columbus Jets but was released in early March. Seeing little opportunity for future advancement, the 36-year-old retired.

Burtschy entered the trucking industry where he served as a freight salesman for several companies for many years. Around 1963 he married Cincinnati native Jacqueline Cecilia “Jackie” Heffernan. They were introduced by Jackie’s sister Pat, who was dating and later married a friend of Burtschy’s. Jackie burnished her own athletic résumé playing volleyball, basketball, and baseball at Seton High School in the Queen City. And the couple’s combined athleticism extended to each of their children: their son Michael played college football and baseball; daughters Kathy and Mary Beth played college softball and volleyball. Kathy’s sons were part of Cincinnati’s LaSalle High School football team that won the Ohio’s Division II State Championship in 2014.

In 1997, he was inducted into Roger Bacon High School’s Hall of Fame.9 On May 2, 2004, a month after his 82nd birthday, Burtschy died of heart failure at Mercy Franciscan Hospital—Western Hills, Cincinnati. He was survived by his wife of 40 years, Jackie Heffernan Burtschy, and five children.

Possessing an extraordinary fastball, Burtschy never mastered the control necessary to build a longer career. He concluded his five-year major league stint with a record of 10-6, and a 4.71 ERA in 185 1/3 innings.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Mary Beth Burtschy and Kathy McNally for their invaluable input. Further thanks are extended to Rod Nelson, Chair of the SABR Scouts Committee, and Tom Schott for review and edit of the narrative.

Ancestry.com

Notes

1 Some off-season transaction, lost to history, doubtless accounted for this.

2 “USS Ticonderoga (CV14),” accessed February 7, 2016, http://navysite.de/cv/cv14.htm.

3 “Jovial Jim Snaps Whip to Instill Life in Sad Sam,” The Sporting News, March 5, 1952: 19.

4 Manager Dykes was obsessed with carrying only 10 pitchers; as events played out Bevan soon followed Burtschy to Ottawa.

5 “International League,” The Sporting News, July 8, 1953: 28.

6 “A’s Lose One to the Orioles – in the Draft,” ibid., December 9, 1953.

7 “A’s List 19 on Hill, But Only 3 Are Sure of Sticking Around,” ibid., February 22, 1956: 24.

8 “Gimmick Tallies Offset Droop in A’s Mound Corps,” ibid., May 16, 1956: 18.

9 “Roger Bacon High School,” accessed February 7, 2016, http://www.rogerbacon.org/hall-of-fame.

Full Name

Edward Frank Burtschy

Born

April 18, 1922 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

May 2, 2004 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.