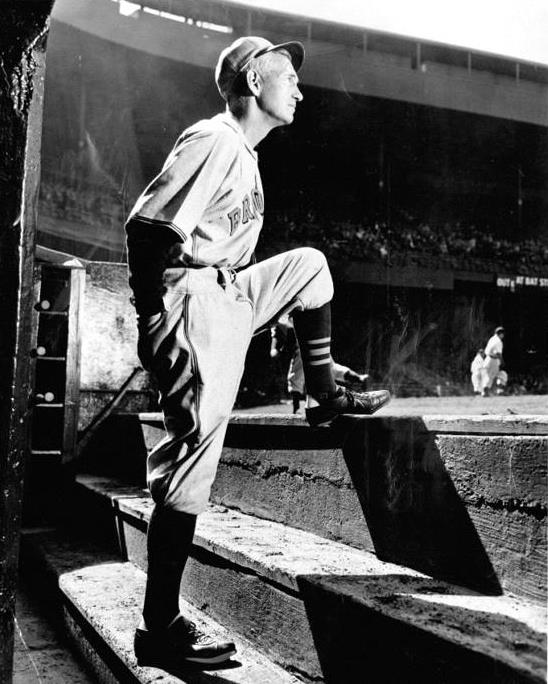

Muddy Ruel

From playing in the schoolyards and sandlots of St. Louis to scoring the winning run in Game Seven of the World Series; from wearing the “tools of ignorance” to holding the title of general manager; from to being a short, skinny, 19-year-old rookie to being special assistant to the Commissioner of Baseball, Muddy Ruel wore many hats in the game of baseball. Ruel, in fact, spent almost his entire life connected to the game in some fashion. And though his name is one that is probably not that familiar to many younger fans of the game, at one time, “Muddy” essentially was a household name.

From playing in the schoolyards and sandlots of St. Louis to scoring the winning run in Game Seven of the World Series; from wearing the “tools of ignorance” to holding the title of general manager; from to being a short, skinny, 19-year-old rookie to being special assistant to the Commissioner of Baseball, Muddy Ruel wore many hats in the game of baseball. Ruel, in fact, spent almost his entire life connected to the game in some fashion. And though his name is one that is probably not that familiar to many younger fans of the game, at one time, “Muddy” essentially was a household name.

Herold Dominic “Muddy” Ruel was born February 20, 1896, in St. Louis, Missouri. His father, George Ruel, was a city police officer. Ruel’s mother, Mamie Ruel nee Gallagher, passed away in 1905 when young Herold was nine years old. After his mother’s death, the young Ruel and his family moved in with Ruel’s paternal grandmother, Philomene Ruel.1

The origin of the nickname “Muddy” has more than one explanation. One story is that the young Herold came into his house covered in mud after playing outside. At which point, his father looked at him and said, “Well, there’s Muddy.” Another version attributes the moniker to Ruel having mud splattered on his face from catching a thrown ball that was made of mud. Yet, another version indicates that the name originated with Ruel’s use of a “dirty” tongue in an attempt to psyche out opposing hitters. It is most likely that one of the first two stories is closest to the accurate origin of the nickname. Other stories suggested that Ruel never used language that was any courser than “rogue” or “dag-gum it.”2

Muddy played both basketball and baseball at Soldan High School in St. Louis, though baseball was his strongest sport. However, during his senior year a small scandal broke that Ruel and three other high school players (including pitcher Holland Chalfant, Ruel’s battery mate with Soldan High and the Wabadas) were no longer eligible to play as amateurs for their respective high school baseball teams. The contention was the Ruel and the other players had received remuneration for their time with the Wabadas (named for the street, Wabada Avenue, on which the team’s ballfield was located) and other ”semipro” teams on the sandlots of St. Louis. On one occasion while playing for the Wabadas, a certain number of spectators at the game took up a small collection and presented the young Ruel with the purse for hitting a home run to win the game for the Wabadas. John B. Sheridan used his position at the St. Louis Globe-Democrat to lobby for Ruel’s cause but the city school officials and the principals of high schools involved ruled against the young players and thus Ruel and the three other players were forced off their high school teams.3

Ruel spent the summer toiling behind the plate for the Wabadas. The team played very well through the summer, in fact, the team did not lose a game until the Fourth of July. The Wabadas copped the Trolley League flag. Ruel and Chalfant formed a star battery that carried the team for the bulk of the season.4

In October, the Wabadas played the Alpen Braus in a best-two-out-of-three-game championship series with theTrolley League title in the balance. The games were held at Sportsman’s Park (home of the St. Louis Browns). The Wabadas won the first two games and thus ended the series as champs.5

In November 1914, on the heels of the Wabadas’ win of the Trolley League title, Ruel was signed by Branch Rickey, on the recommendation of local bird dog Charley Barrett, to play for the St. Louis Browns. The Sporting Life summed up Ruel’s talent as “the best semi-professional backstop in this section” and he “throws well, receives nicely and is regarded as a good hitter.”6

By today’s standards, perhaps it is hard to imagine that a man who was only 5’9” tall and 150 pounds would last nearly 20 years as a big-league catcher. Ruel’s measurements likely would place him as a middle infielder, not a backstop.

Ruel went to spring training in Texas with the Browns in 1915 where he made a very favorable impression on the players young and old with the second stringers throughout the spring. One article conveyed this point. On the way back to St. Louis from the spring training locale in Texas, the team was playing an exhibition game in Kansas. During one of the games, Ruel was struck on the hand by a foul ball. The ball split open his finger and Ruel had to receive some minor medical attention on the field for the injured digit – during which time the entire team of yannigans gathered round the rookie catcher and fretted over his injury.

Ruel eventually earned a spot with the Browns and made his major-league debut with the Browns late in May. Early in the summer Ruel split his time between the Browns and the semipro Missouri State Life team in St. Louis.7 But by July, and for the rest of the season, Ruel was traveling full-time with the Browns as the third-string catcher behind Hank Severeid and Sam Agnew. And, like many men young receiving a big-league paycheck, Ruel used his earnings to purchase a new car.

Ruel spent the next two seasons in the minors (1916 and 1917) with the Memphis Chickasaws (Chicks) of the Southern Association.

As was the case with other young men of age at the time of World War I, Ruel was drafted. He was inducted into the Army in 1918 for a stint that lasted less than a year. While in the service Ruel played on the baseball team at Camp Pike along with fellow St. Louisan, Ray Schmandt.8

Ruel spent the remainder of the 1918 season and all of 1919 and 1920 with the New York Yankees. The Yankees were not yet the powerhouse they would later become. Babe Ruth was still with Boston and the Yankees had yet to appear in a World Series.

On August 16, 1920, Ruel was a witness to one of the most tragic events in baseball history. Ruel was behind the plate when Carl Mays’ fateful pitch struck and killed Ray Chapman.

Later in the season, Ruel described the tragic event in detail to his old friend John B. Sheridan, who used Ruel’s insights for his column in The Sporting News. He made it clear in his eye-witness account that Carl Mays was not guilty of trying to kill Chapman. Ruel’s assessment was that it was a tragic accident.9

In December 1920, Ruel was part of an eight-player trade with the Red Sox. Ruel, along with Del Pratt, Sammy Vick, and Hank Thormahlen went to Boston in exchange for Waite Hoyt, Harry Harper, Wally Schang, and Mike McNally. Ruel stayed in Boston for two seasons, 1921 and 1922.10

During the months of the offseasons, Ruel attended law school at Washington University (St. Louis). He passed the Missouri state bar examination in January 1923. When asked of his reasoning for working toward a law degree, Ruel said in simple practicality, “I want to have a profession to fall back on when I am through with baseball.”11

In 1923 Ruel began his first season with the Washington Senators during the Senators’ finest period. In 136 games for the Nats, Ruel batted .316 with 54 RBI and 24 doubles. His fielding percentage was .980 in 133 games behind the plate.12

Connie Mack, the elder statesman of the Philadelphia Athletics and himself a former big-league catcher, paid high praise to Ruel’s ability behind the plate in 1923. Mack said, “Ruel is the best catcher in either major league this year. . . . He has handled his pitchers in fine style and has been a terror at the bat. . . . he is tireless, the type of catcher that makes every player on his club perk up. Ruel . . . is easily the best catcher of the year in every department of play.”13

Ruel was essentially the everyday catcher for the back-to-back pennant-winning Senators in 1924 and 1925, appearing in 149 games in 1924 and 127 games in 1925.

In the 1924 World Series, the Senators met the mighty New York Giants. Despite going hitless in every at bat in the series until Game Seven, Muddy Ruel caught every game of the series. Bucky Harris, the young player/manager of the Senators, liked his chances with Ruel behind the plate despite Ruel’s poor performance at the plate. Harris’ faith in Ruel’s ability paid big dividends when Ruel eventually scored the winning run that gave the Senators their one and only World Series title.

In the bottom of the 12th, the game tied 3-3, the Series was on the line with every at-bat. Ralph Miller led off for Washington and made the first out. Up next was Ruel. Muddy had been hitless the entire series until he connected for a single in the eighth. Ruel popped a foul ball up behind home plate. Hank Gowdy tossed his mask aside and followed the flight of the ball. It should have been an easy out but Gowdy stepped in his face mask and stumbled, dropping the ball. “Like a sinner forgiven,” as he himself later described it, Ruel had another chance at the plate. On the very next pitch, Muddy smacked a double. The next batter was Walter Johnson, who had been called into the game as a reliever in the bottom of the ninth. Johnson connected for a single but Ruel was unable to advance on the hit. Centerfielder Earl McNeely was next. He hit a sharp grounder to Freddie Lindstrom, the Giants’ third sacker, tried to field the ball but it hit a pebble and bounded over Lindstrom’s head. Ruel, who was not known for his speed on the base paths, was able to score from all the way from second and, at long last, the nation’s capital went wild with its first World Series’ title.14

An article in the The Sporting News highlighted the fact that Ruel received a little long distance advice from his old friend John B. Sheridan prior to Game Seven. Sheridan, who was back in St. Louis and unable to attend the World Series in person, sent a telegram to Muddy with a little advice on his approach at the plate: “Probably swinging too late; pick only good ones, step in close.”15 As history unfolded in the Series finale, the advice seemed to work.

In Ruel’s own words after clinching the Series, with his boyish excitement coming through:

“Don’t tell me the breaks of the game don’t either make you or break you. If Gowdy had caught my foul—an easy one—in the twelfth, I’d never have gotten a change to double and later bring in the winning run. But he did, and I did, and that’s why we’re champs. Hot doggie.”16

Through the years, Ruel marked this day as his greatest day in baseball. Scoring the winning run in extra innings in Game Seven of the World Series does make for a fond memory.

Almost as soon as the Series was over, Ruel left for a tour of Europe with a team of American League barnstormers traveling with and competing against a team of National Leaguers headed by John McGraw, the manager of the recently-vanquished Giants.

In 1925 the Senators were back in the Fall Classic but this time the glory went to their opponents, the Pittsburgh Pirates. The Series again went a full seven games and Muddy Ruel again caught in all seven contests.

On September 30, 1927, Ruel was again present for one of baseball’s famous historic moments. Ruel was the catcher for the Senators in the eighth inning when Babe Ruth hit his 60th home run of the season.

In December 1930, Ruel was dealt by the Senators to the Boston Red Sox. In August 1931, the Red Sox traded Ruel to Detroit. Ruel was signed by the Browns in December 1932 and spent the 1933 season back home in St. Louis with the Browns. The Browns released Ruel after the season and then Ruel was picked up by the Chicago White Sox to play in a reserve capacity and serve as a pitching coach.

In 1935 Ruel began working as the pitching coach for Jimmy Dykes and the Chicago White Sox. Ruel held this post for more than a decade, through 1945, occasionally getting the opportunity to manage the club when Dykes was absent from the dugout for being ejected from a game or for health reasons.

Muddy Ruel married Dorothea Wester on December 10, 1938 at St. Thomas Catholic Church in Chicago.17 The marriage would ultimately result in four children for the couple.

In addition to his duties as pitching coach with the White Sox, Ruel proved that he was a well-rounded individual outside of the foul lines. In the spring of 1944, the White Sox trained in French Lick, Indiana due to wartime travel restrictions. During a stretch of snowy weather, the team was forced to exercise indoors in the convention hall of their hotel. The hall served as a makeshift gymnasium and it was equipped with a piano. Ruel sat down at the keys to provide musical accompaniment for Indian club swinging sessions. This led one sportswriter to comment that Ruel’s playing, “makes for more rhythmic swinging, tho Muddy doesn’t play anything but classical stuff and waltzes.”18

On November 3, 1945, it was announced that Ruel would be leaving the coaching ranks effective December 15, 1945, in order to put his law degree to work by serving as the special assistant to the new Commissioner of Baseball, A.B. “Happy” Chandler. One newspaper quoted Ruel on his new job, “It is very gratifying to me to receive the appointment . . . and I’m sure everything will work out for the general benefit of baseball.”19

Given an opportunity to use his law skills, Ruel took the post of special assistant to Commissioner A.B. “Happy” Chandler in 1945 and 1946. During this tenure in the Commissioner’s office, Ruel extensively traveled around the country on “the knife and fork circuit” to promote the sport of baseball and proclaim the benefits of boys playing baseball to encourage physical activity.

In September 1946, Ruel was hired away from the Commissioner’s office to be the manager of the St. Louis Browns. Ruel signed a two-year contract to manage the Browns for 1947 and 1948.20

In September 1946, Ruel was hired away from the Commissioner’s office to be the manager of the St. Louis Browns. Ruel signed a two-year contract to manage the Browns for 1947 and 1948.20

Unfortunately, the act of returning to his hometown was not kind to Ruel. The Browns struggled all season and spent almost the entire season in the American League cellar.

The season began with a fair amount of optimism with many writers predicting the team could finish in the first division. Happy Chandler, the commissioner of baseball, was present for opening day for the Browns at Sportsman’s Park to wish his former employee well in his new endeavor as a big league skipper. Unfortunately, Hal Newhouser and the Tigers spoiled the fun, winning easily, 7-0.21

By July the team had fallen into the cellar and attendance was very low. The front office sought a way to breathe life into the team and sell more tickets. The Browns’ vice-president and general manager was William O. DeWitt. He was once a young protégé of Branch Rickey when Rickey was still in St. Louis. Rickey plucked DeWitt from the concessions workforce and made him an office boy and set the young DeWitt on a career path toward the upper echelons of the front office. After watching the large crowds turning out to watch Jackie Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers visit Sportsman’s Park to play the tenant Cardinals, the Browns’ front office began to understand the economic benefits of integration. DeWitt sent the Browns’ chief scout, Jack Fournier, to seek talent in the Negro Leagues. After observing the Kansas City Monarchs and Birmingham Black Barons, Fournier made his recommendations to DeWitt. And so, the last-place Browns became the third major league team to integrate. On July 17, the Browns purchased a 30-day option on Lorenzo “Piper” Davis of the Black Barons and Chuck Harmon was signed to a minor-league contract and sent to Gloversville-Johnstown, New York, in the Browns farm system. The Browns also signed Henry Thompson and Willard Brown to contracts and in the process became the first team to have more than one African-American on the same roster.22

Needless to say, while the Browns were making big news in the world of baseball, the team was quickly unraveling, making Ruel’s job more stressful. Now Ruel found himself not only trying to right a sinking ship, he was now asked to integrate his workforce while some of the crew sought seats in the lifeboats. One player in particular, Paul Lehner, a promising young outfielder from Alabama, went to the front office demanding a pay raise or his release from the team. Ruel coaxed the young Lehner into staying with the team. But three days after the signing of Thompson and Brown, Lehner showed up late to the ballpark for the afternoon game with the Red Sox. The reason given for Lehner’s tardiness was that he had injured his leg in the previous day’s game. Ultimately, Lehner entered the game in the late innings as a pinch hitter. The Browns fined Lehner for his behavior and when Lehner saw his next paycheck he was less than thrilled.23

Meanwhile, Thompson and Brown were attempting to earn a spot on the team and make good in their opportunity in the American League. Thompson played second base regularly during the absence of Johnny Berardino who was out with a broken hand. Brown, however, did not see much playing time and was used mostly as a pinch hitter. Unfortunately for Brown, his batting average likely suffered from not seeing American League pitching on a daily basis.24

Sam Lacy, a prominent sportswriter in the African-American press and future inductee of the baseball Hall of Fame, interviewed Muddy Ruel a couple of weeks into the Browns’ experiment with integration. Lacy wrote that it was “refreshing” to see firsthand that Ruel was giving Brown and Thompson every opportunity to prove themselves as ballplayers, not as black ballplayers. Ruel told Lacy that he was watching Brown and Thompson “just as I watch every man on the team.” Ruel further stated that Brown and Thompson were “no different than Vern Stephens with me,” referring to one of the Browns’ best players. Lacy walked away from this interview feeling Ruel never hinted at the fact that Lacy was interested in Brown and Thompson because of their race. Lacy added, “. . . each time he spoke of Brown or Thompson, it was as though either or both were just two new men—not two COLORED men.”25

After approximately six weeks of integration, the Browns released Thompson and Brown. The two players passed through on waivers with no other takers in either league. They returned to the Kansas City Monarchs and the Browns were once again an all-white ballclub. Though the Browns road attendance was up, the attendance at home in St. Louis remained low during the period that Thompson and Brown were with the team and the team remained in last place in the standings and that is where the Browns finished the season.26

But before the end of the season, Ruel was once again put in an awkward position by one of DeWitt’s attempts to boost attendance. At some point during the dreary 1947 campaign, the Browns’ radio color commentator, Dizzy Dean, in classic braggadocio, said he could come down out of the radio booth and pitch better than ball than the tired arms on the Browns’ pitching staff. On September 17, Ed Smith, director of public relations for the Browns, signed Ol’ Diz to a contract with the idea being that Dean would pitch one or two games on the final homestand of the season.27

Meanwhile, Ruel and his team were toiling on the road in Boston. When asked by the press about the signing of Dean, Ruel replied, “I’ve heard nothing at all about it.” Adding, “All I know is the club has received letters from the fans saying how they enjoyed Dean’s broadcasts and how wonderful it would be if he could pitch a game for the Browns.” But, in an answer that perhaps revealed his disapproval of the publicity stunt, Ruel replied “no comment” when asked if he would use Dean as a pitcher.28

With much excitement for a last-place team, the fans turned out in big numbers to see Dean start the last game of the season for the Browns. Nearly 16,000 (paid attendance was listed as 15,916) fans packed into Sportsman’s Park on Sunday afternoon to see if Ol’ Diz could still pitch. He pitched four scoreless innings and was 1-for-1 at the plate. Following his single in the third inning, he tried to beat a throw to second on a force play. Ol’ Diz “slud” into second and came up with a pulled muscle. He took his turn on the mound in the fourth but the leg muscle pain was enough to force him from the game after he finished the frame. According to one account, Ruel said after the game, “Some pitchers are great and some are great pitchers—Dean belongs to the alltime great class.”29 However, another account suggests that Ruel still resented the front office’s publicity stunt and he did not even manage the ballgame. He instead handed the duties off to bench coach Fred Hoffman.30

A newspaper column earlier in the season suggested there was friction between Muddy Ruel and vice president and general manager Bill DeWitt Sr. One rumor involved Ruel leaving the field manager’s position to replace DeWitt as general manager. In light of such turmoil, it is not surprising that Ruel was fired but Ruel himself was taken aback by the dismissal. He was under the impression he had two years to turn the team around since he was working under a two year contract. Ruel even paid a visit to Richard Muckerman’s office at the City Ice and Fuel Company to get a more personal explanation for the dismissal.31

After being dismissed by the Browns, Ruel was a quickly hired as a coach with the Cleveland Indians. In less than a year, Ruel went from managing the last place Browns in 1947 to being part of Lou Boudreau’s brain trust that helped the Indians win the World Series in 1948.

Ruel eventually graduated to the position of Farm Director of the Indians in 1950. He stayed in that position for a year. Ironically, when Ruel left the job of Farm Boss in Cleveland, the man named to replace him was Mike McNally, one of the players whom the Red Sox traded to the Yankees to receive Muddy Ruel back in 1920.32

After leaving Cleveland, Ruel went to Detroit, where he served as farm director and then graduated to the post of general manager from 1954 to 1956. The Briggs family sold the team in October 1956 and Muddy Ruel went from being general manager to special advisor to the new ownership group, while Spike Briggs moved into the role of general manager. Ruel remained in that position for a few months until he took a one-year leave of absence from his post with the Tigers and moved his family to Italy so that his children could study abroad. However, about ten months into his yearlong leave, Ruel resigned and left baseball for good.33

Perhaps after 40 years in baseball, Ruel had decided to retire and enjoy more time with his wife and four children. At this point, the Ruel family moved to Palo Alto, CA.

In January 1963, Ruel suffered a heart attack and was hospitalized for a few days. Later in the year he suffered another heart attack and passed away on November 13, 1963.34

Ruel, throughout the course of his career, was often a man of few words in his many dealings with the press. When he did speak it was only after careful consideration of his words. In his many years as a coach, he worked to supply the players around him with the tools they needed to succeed in the game and to avoid making mistakes. Once he summed up his philosophy of coaching and of the game:

“This game of baseball is so beautiful, mainly because it’s so simple. The Good Lord every season supplies approximately 400 men and boys in this country with the physique and the mechanical ability to play in the major leagues. Given that good health and that skill, they’re sure to succeed—unless they make mistakes. So, that’s the basis of my operation. I try to keep them from making mistakes.”35

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Joan Thomas for kindly helping me with all aspects of this article.

Notes

1 St. Louis Police Department records; St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 10, 31, 1905; US Census data, 1910; Marriage License for August Ruel and Philomene Bourdonné, St. Louis, MO.

2 Al Schacht, “I Always Had More Fun Than Anybody,” Sports Illustrated, March 21, 1955; Atlanta Daily World, July 26, 1963.

3 St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 12, 1914; April 14, 1914; April 16, 1914.

4 St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 5, 1914.

5 St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 19, 1914.

6 St. Louis Globe-Democrat; St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 26, 1914; Sporting Life, November 21, 1914.

7 St. Louis Globe-Democrat 1915; St. Louis Post-Dispatch 1915.

8 Draft records, Missouri Secretary of State; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 26, 1918; St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 26, 1918.

9 John B. Sheridan, “Back of the Home Plate,” The Sporting News, September 23, 1920.

10 www.retrosheet.org

11 The Lima News, January 13, 1923; The Bismarck Tribune, January 16, 1923.

12 http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/R/Pruelm101.htm

13 “Connie Mack Likes Ruel,” The Sandusky Journal, October 19, 1923.

14 Carmichael, My Greatest Day in Baseball. Pp. 58-62. New York Times, October 11, 1924; The Washington Post October 11, 1924.

15 The Sporting News, 1924.

16 The Washington Post, October 11, 1924.

17 Chicago Daily Tribune, December 11, 1938.

18 Chicago Daily Tribune, March 21, 1944.

19 Chicago Daily News, November 3, 1945.

20 “Ruel-ing the Browns,” Baseball Magazine, December 1946; St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 22, 1946; St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 21, 1946.

21 New York Times, April 16, 1947.

22 St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 1947; St Louis Post-Dispatch, July 1947; St. Louis Star-Times, July 1947 ; The Sporting News, July 23, 1947.

23 The Sporting News, July 30, 1947.

24 The Pittsburgh Courier, August 23, 1947; New York Amsterdam News, August 23, 1947.

25 Sam Lacy, “Looking ‘em Over,” Richmond Afro-American, August 9, 1947.

26 Atlanta Daily World, August 26, 1947; The Chicago Defender, August 30, 1947; New York Times, August 24, 1947.

27 Chicago Daily Tribune, September 18, 1947; The Washington Post, September 18, 1947;

28 St. Louis Star-Times, September 17, 1947.

29 St. Louis Star-Times, September 29, 1947.

30 “Short Noisy Return of Dizzy,” Sports Illustrated, September 28, 1964.

31 Sid Keener, St. Louis Star-Times, 1947.

32 The Christian Science Monitor, November 30, 1950; Chicago Daily Tribune, October 15, 1951; The Hartford Courant, October 18, 1951; The Washington Post, October 15, 1951; The Hartford Courant, November 9, 1951.

33 Detroit; New York Times.

34St. Louis Globe-Democrat, November 15, 1963; St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 14, 1963; New York Times, November 15, 1963.

35 “Looping the Loops,” The Sporting News, April 5, 1940.

Full Name

Herold Dominic Ruel

Born

February 20, 1896 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

November 13, 1963 at Palo Alto, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.