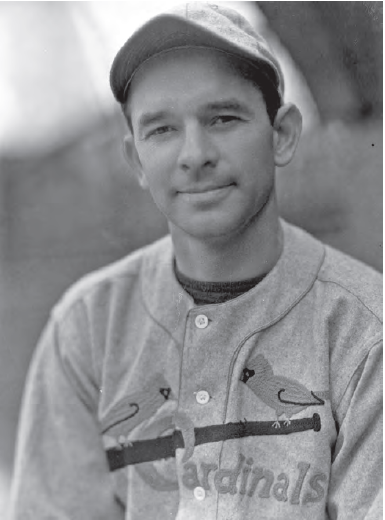

Pat Crawford

Pat Crawford was a reluctant professional baseball player. A devout Christian with a passion for baseball, Crawford objected to playing on Sundays. When he graduated from college in 1923 and accepted a position as teacher and coach at a high school in North Carolina, he anticipated that a career in baseball would be impossible to reconcile with his personal convictions and school-related responsibilities. But Crawford was a thinking man and found the perfect solution in the Class B South Atlantic (Sally) League: Start the season late and end early to accommodate his teaching schedule. Among the league’s best hitters from 1924 to 1927, Crawford spurned offers from higher minor-league teams, refusing to change his principles. He ultimately compromised, signed with the New York Giants, and debuted with them in 1929. He abruptly retired after the 1930 season, but was lured by the St. Louis Cardinals to sign with them. After two seasons with the Columbus Red Birds (and an American Association MVP award in 1932), Crawford cemented his reputation as a versatile infielder and clutch pinch hitter in 1933 and 1934. His playing career came to a tragic halt when he developed a life-threatening blood infection in 1935, leaving him with a permanent limp.

Clifford Rankin “Pat” Crawford was born on January 28, 1902, in the bucolic town of Society Hill, Darlington County, in the northern part of South Carolina. His parents, James and Sallie (Ford) Crawford, were South Carolinians by birth and raised five children. Cliff, as his parents and friends called him, was followed by Alda, Lafon, Thomas, and William. His father, a salesman for a retail grocery company, moved the family to Dillon County and by 1915 to Sumter, a growing town of about 9,000 residents in the geographic central part of the state. An athletic youngster, Pat attended Sumter High School, where he excelled in the classroom and on the athletic fields, starring in baseball, basketball, and football. After graduating in 1919, he attended Davidson College, a prestigious liberal-arts college about 20 miles north of Charlotte, North Carolina. Guided by his faith, Crawford was active in his institution’s YMCA and served as the vice president of his senior class. He forged an impressive athletic résumé, serving as captain of the basketball and baseball teams, and twice being named all-state as an infielder. He graduated with a B.A. in physical education.

Standing 5-feet-11 and weighing about 160 pounds in college, Crawford was quick and agile, and learned to play all infield positions. With his speed, natural instincts, and strong throwing arm, he was also an effective outfielder. Crawford’s foray into professional baseball began in 1922, when he was signed by owner-manager and former big-league pitcher George Suggs to play left field for the Kinston (North Carolina) Highwaymen in the independent Eastern Carolina Baseball Association, which existed outside the jurisdiction of Organized Baseball.1

Despite Crawford’s passion for baseball, he considered some aspects of professional ball distasteful, such as Sunday games, the hard living (drinking and carousing) of some players, and the time it took away from family. In the summer after he graduated from Davidson College, he returned to Kinston to serve as player-manager for a local semipro team in the Blue Ridge League. (The Highwaymen had disbanded after the 1922 season.) Not long after the season started, Crawford was offered a bonus of $150 by Dick Hoblitzell, manager of the Charlotte Hornets, to play in the Sally League; however, he had not yet decided if he wanted to a career in baseball.2 He filed the contract at home and finished the season with a semipro team in Lenoir.

Crawford accepted a job as a teacher and coach at Gastonia High School, about 20 miles east of Charlotte, believing that his active baseball career was over. From the fall of 1923 through the end of May 1927, he established a reputation as a “mentor and idol of high-school athletes” and led the Green Wave to a football championship and baseball prominence.3 During the spring baseball season in 1924, Crawford was surprised when Charlotte owner Felix Hayman inquired about his availability for the coming season. Crawford asked if he would be permitted to play for a semipro team in Abbeville, South Carolina. Hayman agreed with the stipulation that Crawford would report to the Hornets on a day’s notice. “I packed up and went to Abbeville, arriving there on a Friday,” Crawford said. “I worked out with the team Saturday and was all set to play Monday. Sunday I received a wire from Mr. Hayman telling me to report at once to take the place of the regular first baseman who had been injured. So without playing a single game with Abbeville, I boarded the train for Charlotte and began my professional baseball career on Monday at first base.”4 Crawford replaced injured future big leaguer Chick Tolson at first base and was later switched to third base. For the second-place Hornets, the 22-year-old left-handed hitting Crawford batted .303 (114-for-376).

Purchased after the season by the Louisville Colonels of the Double-A American Association, Crawford refused to report to the team, citing his objection to playing on Sundays. Further complicating matters was his insistence on finishing the baseball season as coach at Gastonia High School. Louisville loaned him to the Greenville (South Carolina) Spinners of the Sally League to start the 1925 season.5 About three weeks after reporting to his new team, Crawford replaced player-manager Zinn Beck, who had unexpectedly resigned, and was charged with “pull[ing] the slumping team together.”6 In an offensively-minded league, Crawford batted .343 (20 players with a minimum of 300 at-bats batted at least .340) in 89 games. As he did in subsequent years, he left the team early to return to his teaching and coaching duties in high school.

Nicknamed Peppery Patrick and Captain Pat for his feisty personality and leadership abilities, Crawford was described by local papers as one of the “finest characters in baseball” for his unwavering commitment to his high-school athletic program, exemplary behavior, and excellent play on the field.7 For the second consecutive season, he refused to report to his new, higher-level team (the Atlanta Crackers of the Class A Southern Association), which had acquired his contract in midseason, and claimed that he would quit baseball before he would turn his back on his teaching career. In his second of three seasons with Greenville, Crawford batted .328 (146-for-445), developed a home-run stroke, belting 21, and knocked in 93 runs. Behind the pitching heroics of 30-game winner Wilcey Moore, the Spinners won the league title and then defeated the Richmond Colts of the Virginia League for the Southern Championship.8

By the beginning of the 1927 season, there seemed to be a consensus that the coming year with Greenville will “probably be [Crawford’s] last in professional baseball” when Atlanta sold his contract to Greenville.9 Fueling the rumors of his imminent retirement from baseball was his resignation from Gastonia High School to accept a position as head coach and faculty member at Guilford College in Greensboro, North Carolina. Crawford was considered “one of the best infielders of the Sally League” who might have already been in the majors had he been willingly to play baseball on Sunday.10 Crawford reported to the Spinners in June, had his best season so far, and was named the league’s most valuable player.11 He hit .334 (148-for-443), knocked in 90 runs, and clubbed 24 home runs, the third most in the league, despite missing 30 games for player-manager (and owner) Frank Walker’s second consecutive (league and Southern) championship team.

John “Little Napoleon” McGraw, manager of the New York Giants, was not someone who accepted no for an answer. On scout Dick Kinsella’s advice, McGraw personally scouted Crawford in 1927. Making his best sales pitch to Crawford and Walker, McGraw persuaded Crawford to report to the Giants the following spring and purchased his contract for $10,000.12 The news hit the printing press on August 3 and its publication met with a thundering ovation in Greenville and Gastonia. “A more popular ball player has never been in the South Atlantic Association,” excitedly reported the Gastonia Daily Gazette.13

In Gastonia, Greenville, Charlotte, Sumter, and other areas where Crawford lived and worked, he was seen as more than just a ballplayer. He was humble, modest, and self-effacing, sincerely concerned about education, and seemed to harken back to another, less complicated era. He embodied the notion of sports as an ennobling undertaking. Newspapers predicted success in the major leagues because Crawford was a “natural, quick thinker” who “puts his whole soul” into baseball.14 In a rapidly changing society in which individuality and egoism were commended, Crawford possessed the “mental and moral fitness to be a star.”15

Crawford decided not to report to the Giants spring training in 1928, reiterating his commitment to Guilford College.16 Frank Walker of the Spinners voiced his disapproval, and McGraw, frustrated with Crawford’s obstinacy, claimed he didn’t need a player who did not want to play for the Giants. “[McGraw] is interested in [Crawford] and proposes to use him this season,” reported the Gastonia Daily Gazette near the end of the Giants’ spring camp.17 When the baseball season concluded at Guilford in late May, Crawford announced his resignation and willingness to play professional baseball on his terms.18

The Giants assigned Crawford to their top affiliate in the American Association, the Toledo Mud Hens, piloted by 37-year-old player-manager Casey Stengel. Crawford quickly adjusted to the jump from Class B to Double-A, then a notch below the big leagues. He batted .347 (tied for fifth) in the league among players with at least 400-at bats). He tailored his game to fit the large dimensions of Toledo’s Swayne Field by becoming a slap hitter known for his good eye at the plate, striking out just 15 times in 481 plate appearances. His fielding at first base was as impressive as his hitting. By the end of the season, The Sporting News considered Crawford and Joe Kuhel of the Kansas City Blues “easily the best first base prospects” in the AA.19 Crawford was a late-season call-up to the Giants when the rosters expanded in September, but he did not play.20

When Crawford reported to the Giants’ camp in San Antonio in February, 1929, it was the first time in his professional career that he had participated in spring training. McGraw was determined to whip his team in shape, driven by the still-fresh memory of a disappointing second-place finish, two games behind the pennant-winning St. Louis Cardinals. The Giants were a young team with established major leaguers at the infield positions where Crawford could play. Hitting sensation Bill Terry was one of the best first basemen in the league, and the third sacker, 23-year-old Freddie Lindstrom, was just beginning his Hall of Fame career.

Crawford secured a spot on the Giants roster with his hustle, determination, versatility, and studious approach to the game. He made his major-league debut in the team’s first game of the season, on April 18, when he unsuccessfully pinch-hit for Carl Hubbell in the Giants’ 11-9 victory over the Phillies in the Baker Bowl. On April 27 Crawford pinch-hit for “King Carl” again, and connected for his first big-league hit, a home run into the right-field stands at the Polo Grounds, in the Giants’ 5-4 loss to Boston. “Homer by Crawford Helps Giants Win,” read a headline from the New York Times on May 27.21 Crawford, pinch-hitting for reliever Dutch Henry in a slugfest with the Braves at the Polo Grounds, faced Socks Seibold with the bases full in the sixth inning. On a 3-1 count, Crawford launched an inside fastball over the right-field terrace for his first and only career grand slam to break the game open. Coincidentally, the Braves’ Les Bell blasted a pinch-hit grand slam in the seventh inning to make it the first time in major-league history that two pinch-hit grand slams were hit in the same game. Crawford’s third pinch-hit homer against the Phillies, on June 19, tied Ham Hyatt (1913) and Cy Williams (1928) for the most pinch-hit four-baggers in a season. (Brooklyn’s Johnny Frederick broke that record with six in 1932.)

With little chance to displace Terry or Lindstrom, Crawford carved his niche as a clutch pinch-hitter. He saw action in the field just eight times, including three starts at first base. Two of those starts occurred at the end of the season, when he connected for four hits in seven at-bats and drove in three in runs during inconsequential wins for the third-place Giants. Crawford finished the season with a remarkable 24 runs batted in on just 17 hits (including three doubles and three home runs), scored 13 times, batted. 298, and seemed to have a bright future.

Second base proved to be a problem for the Giants in 1929, when Andy Cohen and Andy Reese combined for 31 errors. Consequently, infield prospect Doc Marshall and Crawford, who had never played second base professionally, competed during 1930 spring training with the two veterans. Marshall won the job, but got off to a poor start, which paved the way for Crawford’s first start at second base, on April 26 in the first game of a doubleheader at Philadelphia (he went hitless in five at-bats). In 13 subsequent starts, Crawford played steady if not spectacular baseball. In seven of his starts, he had at least two hits and twice knocked in four runs. On May 22 the Giants made a stunning trade sending their workhorse right-handed pitcher Larry Benton to the Cincinnati Reds for a slick-fielding second baseman, 29-year-old Hughie Critz, who had finished second and fourth in the MVP voting in 1926 and 1928 respectively. Overnight, Crawford lost his job and was relegated to pinch-hitting duties, despite a .270 batting average and 16 runs batted in from just 20 hits. Six days after the acquisition of Critz, the Giants made another deal with the Reds, exchanging Crawford for outfielder Ethan Allen and pitcher Pete Donohue.

Crawford reported to manager Dan Howley’s Reds en route to a seventh-place finish. On a light-hitting team, he struggled in his first 33 games (which included five starts at first base and seven at second base), hitting just .243. After replacing Hod Ford at second base on August 16, Crawford proved his value by hitting safely in 13 of 14 games (.356 average). Crawford made a seamless transition to second base in 1930. His .968 fielding percentage was above the league average (.963) and just one percentage point lower than that of the Cardinals’ Frankie Frisch. From August 16 through the end of the season, Crawford batted .312, the third-best on the team, trailing only Bob Meusel’s .330 and rookie Tony Cuccinello’s .350.

On December 1, in a “surprising development,” the Reds traded Crawford and outfielder Marty Callaghan to the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League for first baseman Mickey Heath.22 Howley desperately wanted a slugger and was willing to sacrifice Crawford to acquire Heath who had launched 75 round-trippers the previous two years with the Stars. Crawford was disappointed by the trade and in a letter addressed to Stars president William F. Lane wrote, “I am retiring. … Please consider this final. Salary increases are of no interest to me.”23

The news of Crawford’s retirement did not surprise the local media in North Carolina. During his playing days in Kinston, North Carolina, Pat met local resident Sarah Edwards, whom he later married. After living in Gastonia and Charlotte, the couple relocated to Kinston when Crawford began his big-league career. In the offseasons, Crawford taught physical education at local schools, coached basketball, and refereed games. With close ties to his community, Crawford considered the time away from his wife a necessary evil in order to play baseball. Just days after he was officially traded to the Stars, the Crawfords welcomed their first child, Patricia. Pat’s perspective suddenly changed; he was not willing to live almost 2,700 miles away from his family.

Branch Rickey, general manager of the St. Louis Cardinals, sensed an opportunity to acquire a versatile player and orchestrated preliminary discussions among Crawford, Lane, and Larry MacPhail, president of the Columbus Red Birds of the American Association.24 Less than a week before Opening Day, Columbus purchased Crawford’s contract from Hollywood.25

Columbus was historically the weakest team in the American Association, had not enjoyed a winning record since the war-shortened season in 1918, and had finished in last place or next-to-last eight of the previous 12 years. But the team’s history did not matter to Crawford. He was a one-man wrecking crew. Playing his natural position of first base, Crawford led the league in home runs (28) and runs batted in (154), ranked second in hits (237), fifth in batting (.374), fourth in doubles (41), and sixth in triples (13), easily led the league with 388 total bases, and finished third with a .613 slugging percentage.26 Columbus finished in fourth place with an 84-82 record. Despite his phenomenal season, Crawford’s ascendancy to the big-league club was blocked by 27-year-old rookie Ripper Collins, who gradually replaced longtime stalwart Jim Bottomley. Rickey bought Crawford’s contract at the end of the season, but the acquisition could not squelch the rumors that he would trade Crawford at the winter meetings.27

Crawford participated in the Cardinals’ spring training in Bradenton, Florida, but was optioned to Columbus for the start of the 1932 season. In leading the Red Birds to a second-place finish (88-77) and their most wins since 1913, the 30-year-old Crawford finished fourth in batting (.369) and second in home runs (30), runs batted in (140), and total bases (370), and was named The Sporting News Most Valuable Player of the league.

The Cardinals began spring training in 1933 coming off a disappointing sixth-place finish the previous season. Manager Gabby Street, under pressure from GM Rickey and club owner Sam Breadon to produce a winner, viewed Crawford as an ideal insurance policy to shore up an injury-prone infield from 1932. The 31-year-old Carolinian began the season as a pinch-hitter, but then had the opportunity at the end of April to be the regular first baseman when Collins suffered a knee injury. In his 17th consecutive start at first base, Crawford belted a bases-loaded, walk-off single in the tenth inning to defeat the Giants in Sportsman’s Park, 8-7, on May 19. Despite the heroics, he ceded the first-base job to Collins the next day. There was a widespread belief that Crawford would be optioned to Columbus at some time during the season, but the tough veteran proved too valuable.28 The “handy utility man” made 28 starts at first, nine at second base (spelling Frankie Frisch, who had injured his leg), and six at third base.29 He finished the season with a .268 average (60-for-224), but with little pop in his bat (no home runs among his ten extra-base hits) and drove in 21 runs.

Player-manager Frisch, who replaced Street during the previous season, guided the St. Louis Cardinals’ Gas House Gang to baseball immortality in 1934. The Cardinals benefited from an unusually healthy year from its starters (Collins, for example, played every inning of every game). “Crawford played an important part in the success of the Redbirds,” wrote The Sporting News several years after the team’s mythical season.30 An unassuming role-player, Crawford made only five starts all season, but continued to manifest his uncanny ability to hit in clutch situations. Batting .271 in 70 at-bats, Crawford amassed 16 runs batted in on just 19 hits (all singles save for two doubles). He explained that as a pinch-hitter his goal was to make contact and avoid strikeouts (he struck out just 29 times in 651 big-league at-bats). He choked up on the bat in order to connect for a safe hit, and rarely took a full swing with all of his power.31

Crawford’s educated disposition did not cloud his competitive nature. “One of the quietest, most gentlemanly members of our team was Pat Crawford,” said the rough-and-tumble Pepper Martin. “It will probably be a surprise to hear that he turned out to be one of our great jockeys.”32 In the dugout Crawford acted like a coach, encouraging teammates and harassing opponents.

In the Cardinals’ exciting World Series triumph over the Detroit Tigers, Crawford made two pinch-hit appearances. He grounded out to second in Game Four and was retired on a fly ball to right field in Game Five. After those two losses, the Gas House Gang won Games Six and Seven to capture the title. Upon Crawford’s return home to North Carolina, he was feted as a celebrity.

Highly respected in the Cardinals organization, Crawford seemed prepared to transition into a coaching. When George “Specs” Toporcer because of failing eyesight abruptly quit as player-manager of the Rochester Red Wings, the Cardinals’ affiliate in the Double-A International League, team president Warren Giles selected Crawford over Burt Shotton and Ray Blades to lead the team.33

At almost the same time that Giles made the announcement of Crawford’s hiring on January 25, 1935, the 33-year-old jack-of-all-trades was being rushed to the hospital in Kinston. Several weeks earlier Crawford had undergone a routine hemorrhoid operation. He had developed septicemia, a life-threatening blood infection that localized in his liver. He required six blood transfusions and his entire body was inflamed, leading his physician to proclaim that he had only a “slight” chance to survive.34 Papers throughout the Carolinas reported daily on his illness and ultimate recovery. The Charlotte Observer wrote, “[Crawford] is a fine character, the sort that keeps baseball from degenerating to the low level it formerly occupied, [and an] upstanding, high-minded Christian gentleman.”35 Crawford spent weeks recuperating in Kinston Memorial Hospital, but as a result of the disease, he suffered a permanently stiff left hip and his career as a baseball player was tragically ended.36

In his four-year big-league career, Crawford batted .280 (182-for-651) and knocked in 104 runs. He batted .347 over 843 games in his seven-year minor-league career, including a phenomenal .365 average in three seasons in the American Association. Blessed with a positive outlook, Crawford never expressed bitterness or anger about his fate.

Crawford settled in Kinston with his wife, daughter, and son (Clifford, born in 1933) and dedicated the rest of his life to educating youngsters and coaching youth baseball. In 1936 he opened a baseball school and camp in Gastonia for the Cardinals. He scouted for the team and was credited with signing future Cardinals pitcher Ernie White. In Kinston Crawford helped found a recreation department, served as its director for many years, built public baseball diamonds, and organized local youth leagues. In 1937 he and his wife purchased a 20-acre site in Morehead City, North Carolina, about 70 miles southeast of Kinston on the southern edge of the Outer Banks. They established Camp Morehead by the Sea, a youth camp that they operated for many decades. Though he rarely spoke his accomplishments in the big leagues, Crawford proudly participated in reunions of the Gas House Gang. In 1983 he was an inaugural member of the Kinston Baseball Hall of Fame, along with George Suggs and Charlie Keller.

On January 25, 1994, three days shy of his 92nd birthday, Clifford Rankin “Pat” Crawford died in Morehead City and was buried in Westview Cemetery in Kinston. He was the last surviving player from the Gas House Gang. He was posthumously inducted into the Davidson College athletics hall of fame (1998) and the Kinston/Lenoir County Sports Hall of Fame (2012).

Newspapers

Gastonia News Gazette

New York Times

The Sporting News

Online sources

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.com

Notes

1] Bryan C. Hanks, “Clifford was the city’s first recreation director,” Kinston.com, October 10, 2012. kinston.com/sports/local/crawford-was-city-s-first-recreation-director-1.27151

2 H.D. Osteen, “Pat Crawford: A New Type of Big Leaguer,” Sumter (South Carolina) Daily Item, October 29, 1934.

3 “Pat Crawford Hits Homer in First game of Year,” Gastonia (North Carolina) Daily Gazette, May 16, 1927, 2.

4 H.D. Osteen, “Pat Crawford: A New Type of Big Leaguer.”

5 “Baseball Squibs,” Kingston (New York) Daily Freeman, May 13, 1925, 18.

6 The Sporting News, June 25, 1925, 1.

7 “Pat Crawford New Property Atlanta Southern Outfit,” Gastonia News Gazette, July 8, 1926, 2.

8 Marshall D. Wright, The South Atlantic League, 1904-1963: A Year-by-Year Statistical History (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 124-25.

9 “Pat Crawford to Guilford College as Head Coach,” Gastonia Daily Gazette, May 28, 1927, 6.

10 “Pat Crawford Changes Mind About Playing Ball on Sundays,” Pittsburgh Press, August 7, 1927, 1.

11 “Fear Pat Crawford’s Playing Days Are Over“ (Associated Press), Gastonia Daily Gazette, March 28, 1935, 6.

12 “Pat Crawford Sold to New York Giants for $10,000,” Gastonia Daily Gazette, August 3, 1927, 6.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 “McGraw Wants Pat Crawford,” Gastonia Daily Gazette (Gastonia, North Carolina), April 5, 1928, 6.

17 Ibid.

18 “Pat Crawford to Join New York Giants,” Gastonia Daily Gazette, May 24, 1918, 6.

19 The Sporting News, August 16, 1928, 4.

20 H.D. Osteen, “Pat Crawford: A New Type of Big Leaguer,” Sumter Daily Item, October 29, 1934.

21 “Homer by Crawford Helps Giants Win,“ New York Times, May 27, 1929, 31.

22 Alan Gould, “Sports Slants” (Associated Press), Havre (Montana) Daily News, December 19, 1930, 6.

23 The Sporting News, February 19, 1931, 1.

24 The Sporting News, April 9, 1931, 5.

25 “Red Birds Offer Youthful Lineup and Not Done Yet,” Zanesville (Ohio) Sunday Times Signal, April 12, 1931, 8.

26 Bill O’Neal, The American Association. A Baseball History 1902-1991 (Austin, Texas: Eakin Press, 1991).

27 The Sporting News, October 22, 1931, 1.

28 “Columbus Ordered to Cut Its Payroll” (United Press), Ames (Iowa) Daily Tribune-Times, June 5, 1933, 6.

29 “The Lookout,” Lowell (Massachusetts) Sun, July 19, 1933, 13.

30 The Sporting News, March 14, 1940, 3.

31 H.D. Osteen, “Pat Crawford: A New Type of Big Leaguer.”

32 Richard Peterson, The St. Louis Cardinals Baseball Reader (Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2006), 27-28.

33 Jim Mandelaro and Scott Pitoniak, Silver Season: The Story of the Rochester Red Wings (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1996), 59.

34 “Pat Crawford Has Only Slight Chance to Recover,” Gastonia Daily Gazette, January 26, 1935, 2.

35 “Pat Crawford,” from the Charlotte Observer, reprinted in the Gastonia Daily Gazette, February 1, 1936, 4.

36 “Fear Pat Crawford’s Playing Days Are Over” (Associated Press), Gastonia Daily Gazette, March 28, 1935, 6.

Full Name

Clifford Rankin Crawford

Born

January 28, 1902 at Society Hill, SC (USA)

Died

January 25, 1994 at Morehead City, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.