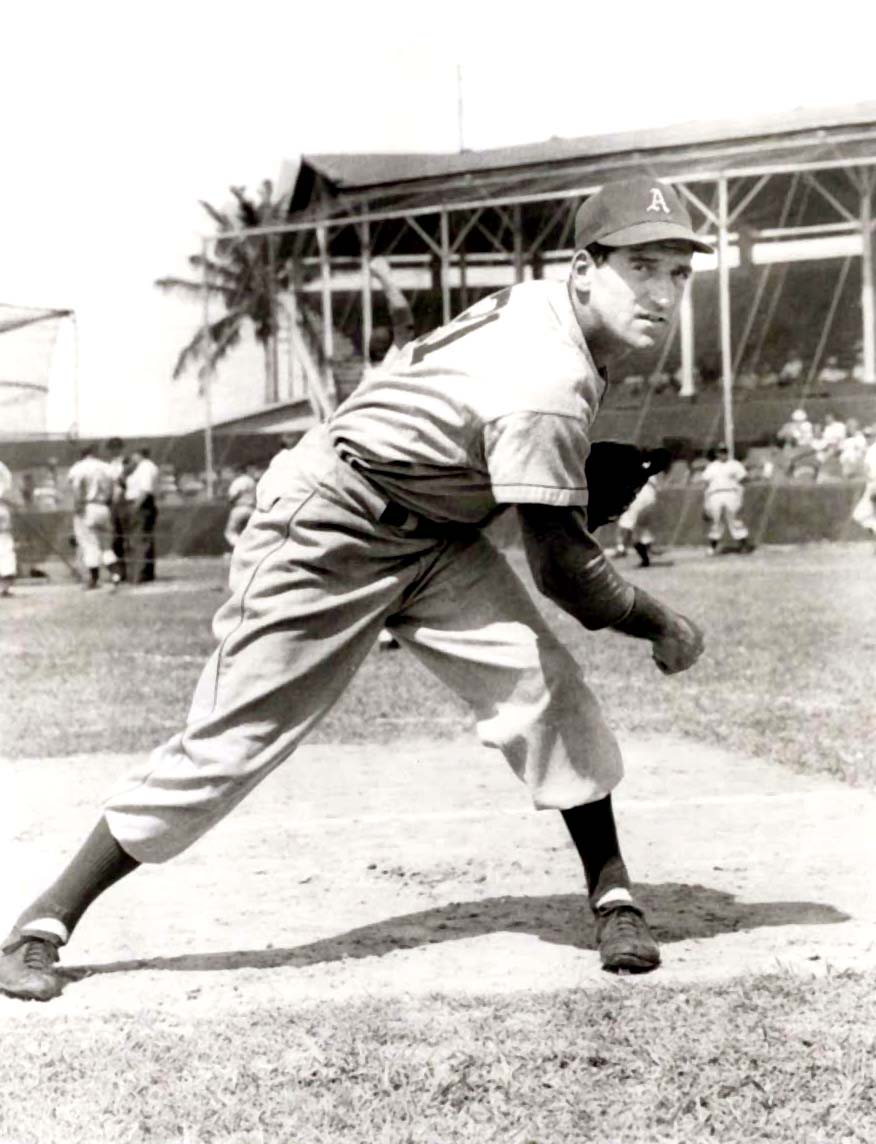

Phil Marchildon

This book is to be neither an accusation nor a confession, and least of all an adventure to those who stared face to face with it. It will simply tell of a generation of men who even though they may have avoided the shells were destroyed by the war.

This book is to be neither an accusation nor a confession, and least of all an adventure to those who stared face to face with it. It will simply tell of a generation of men who even though they may have avoided the shells were destroyed by the war.

–Erich Maria Remarque, All Quiet on the Western Front

Shot down by the Germans in August 1944, Phil Marchildon was captured and spent nine months in a prisoner of war camp. He came back to home and major league baseball a grim, alienated, broken man. It’s been said that no one ever saw him smile again. Whether this is literally true is a matter of conjecture, but the fact remains that although Marchildon survived the war, like many others, he didn’t recover from it.

Philip Joseph Marchildon was born in Penetanguishine (an Ojibway Indian name meaning white rolling sands), Ontario, Canada, on October 25, 1913. The first Marchildon in Ontario as reported by Alain Marchildon was Hector Marchildon, who was born in Quebec on June 17, 1824. Sometime in the year 1840 Hector came to Ontario and purchased fifty acres of land where he built a sawmill. Penetanguishine, a town of about 2,500, is known for its fine farming land. Phil’s father, Oliver Marchildon, was a tinsmith and a plumber. Marchildon’s mother Elizabeth raised the Marchildon family. The Marchildon family’s roots in France go back to the 1700s. Phil had four sisters (Madeline, Viola, Betty, and Jean) and two brothers (Norbert and Francis). Marchildon attended Penentang High School and graduated in 1934. He then went to St. Michael’s College in Toronto for one year. Desiring to be self-sufficient, he quit St. Michael’s and went to work in the Creighton Nickel Mines in Sudbury, Ontario. The family got along moderately well financially, but they also experienced some hard times. There were many happy times especially when all the children were involved in games that were available. As a child Phil helped out the family by delivering the Toronto Star newspaper. Although of French descent, he spoke only English. Information gleaned from the Marchildon genealogy chart showed that a part of the Marchildon family branched off from the French part and considered themselves British. Perhaps that is why Phil and his family only spoke English and lived in English-speaking Ontario. There were also purported to be some Italian forebears.

Marchildon had no contact with baseball until he reached high school. Showing a talent for the game, he soon became a pitcher on the town team. Unfortunately, he had little or no control.

Getting a job with Creighton Nickel Mines near Sudbury, he worked in the mines and played semi-pro ball. Gaining a tryout with the Toronto Maple Leafs through the efforts of Jim Shaw, his former coach, he impressed Leafs manager Dan Howley and was offered a contract. Phil was practically picked out of the mines by “Howling” Dan Howley. Marchildon, after an impressive workout for the Maple Leafs in which he struck out seven of nine hitters he faced, waited around for some time; when no one said anything to him, he got in his car and drove back to Sudbury. Feeling that he hadn’t impressed anyone, Marchildon had gone back to his job in the Creighton Mines. Howley was not going to let him get away and drove all night to Sudbury and literally plucked Phil from the mines as he was preparing to descend on the lift. Howley said, “I put a half-nelson on him and forced a pen into his hand and told him to write his signature. I saved him from being a mole.”

Phil was no youngster of 18 or 19 when he started his professional baseball career in 1939. He was 25, an advanced age for someone starting a baseball career. Sent down to Cornwall in the Canadian-American League, he pitched solidly enough to warrant a return to Toronto. The Philadelphia Athletics purchased his contract in 1940, calling him up in September of that year. He pitched in two games, compiling a 0-2 record and 7.20 ERA in 10 innings on a team that lost 100 games. Athletics pitching coach Earle Brucker saw that Marchildon was throwing the ball across his body, causing his wildness. He helped Phil correct his mechanics of pitching so that his control began to improve.

Although unimposing at 5’10” and 170 pounds, Marchildon had plenty of raw talent that Brucker could work with, especially an extraordinary fastball. He described it with perhaps a touch of exaggeration: “Later on in the majors it was estimated that my fastball traveled about ninety-five miles per hour. The movement on it was so distinctive that it became known around the American League as ‘Johnny Jump-Up.’” It took him a while to develop his curve, which he said “had a wide downward break to it that made it almost as effective as my heater,” adding that his tight grip on the pitch made it only a bit slower than his fastball. A writer for The Sporting News issue of August 2, 1945, attributed Marchildon’s success to an odd physical trait: “The secret of the Canadian’s great fast ball, which is one of the most ‘alive’ pitches to enter the American League, is a powerful muscle that stands up like a marble at the base of his thumb and first finger. He grips the ball like a vise. His knuckle joints also are unusually large like the Village Smithy’s.”

After a brief debut in 1940 Marchildon began to show some promise in 1941, pitching 204-1/3 innings with a decent ERA of 3.57 despite a 10-15 record. His ERA jumped to 4.20 in 244 innings in 1942, but he was learning to win, going 17-14 on a cellar-dwelling club that went 55-99, nine games worse than the last-place edition of the year before.

After his fine 1942 season he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force. Marchildon could have stayed in Canada the entire war as a physical instructor but chose to become a gunner on a Halifax bomber. He was soon sent overseas as a tail gunner. His bomber crew had completed 25 missions over Germany and needed only five more missions to be sent home. On its 26th mission, on the night of August 17, 1944, a German fighter shot the plane down. Bailing out at fifteen thousand feet with another comrade, Marchildon floated to a splashdown in the Sea of Denmark 20 miles from shore. Swimming for four hours, they were constantly being pushed back from shore by the tide. Fully exhausted and ready to give up, they were saved by Danish fishermen The Danish fishing crew pulled Marchildon and his buddy out of the Kiel Canal. The Danish fishermen told them they would be safe with them and they would try to get them back safely to England. However, a German patrol was waiting for them when they got to shore, and the Danes had no choice but to turn them over. Marchildon later learned that the rest of the crew died in the crash.

Phil was sent to Stalag Luft III, the prison camp 105 miles southeast of Berlin that was made famous by the movie The Great Escape. There he lingered for almost nine months and lost 40 pounds from the meager diet of a few pieces of bread a day and some watered down soup the Germans fed him and his fellow prisoners of war. A guard told him that there was a cubic centimeter of wood in each loaf of bread. He said that if it were not for the occasional Red Cross package he might not have survived. In addition, he watched as some of his comrades were murdered for trivial offenses. One such occurrence was when some prisoners were playing a softball game and the ball landed between two barbed wire fences. Any prisoner who crossed over the first fence would be shot. One of the prisoners walked up to a German guard and politely said in German, “Don’t shoot, I am only going to retrieve the ball.” The guard nodded that it was all right, but the moment the prisoner stepped over the fence the guard shot and killed him. When the British liberated the prisoners, the German guard was pointed out, and the British shot him.

Marchildon was freed from his captors by a British patrol on May 2, 1945; one week later the war in Europe was over. Before his freedom he and his mates had been marched around Germany by the Nazis trying to avoid the oncoming Allied forces, especially the Russians. At one point Marchildon and his fellow prisoners of war were forced to march 130 miles in deep snow.

Nowhere near baseball condition, extremely underweight and suffering from attacks of depression, Phil returned to his hometown in Canada to recuperate. There he began to regain his health. However, he was very nervous and could not stand the relative quiet of normal life. The first night he was home in bed he could not sleep and went outside to sleep on the ground. He had many nightmares and nervous sweats from his ordeals. Trying to explain his frazzled nerves, he said, “on every mission I was tense as I scanned the skies looking for fighters who would attack at a moment’s notice. There was no time to relax once you were over enemy territory.”

Returning to the A’s in July, Phil did not expect to pitch for quite a while. He felt he had to work himself back into shape. His mentor Earle Brucker agreed. But Connie Mack held a Phil Marchildon Night, naming Marchildon the starter. It’s worth noting that Marchildon never felt quite comfortable with Connie Mack, regarding him as a tight-fisted old man who never paid him what he thought he was worth. Marchildon was also embittered against Mack when he went into the Royal Canadian Air Force because Mack never said goodbye to him. So before 19,000 fans (a crowd sufficient to make Mack a few dollars) Phil went out to pitch his first game since his return from the war. Pitching two good innings, he hurt his leg and left the game. Phil tried to pitch once more that season, with the same result.

There was more to it than just pitching, however. A fairly open, friendly enough person before the war, Marchildon came back a different, guarded man. As teammate George Kell said, “Phil really changed after his war experiences; he was very serious and rarely spoke about what he had gone through.”

Realizing that he needed more time to recuperate in all ways, Phil went home and spent the rest of the year regaining his spirit and health. Marchildon married Marjorie Irene Patience on November 8, 1945, and they had two daughters, Carol and Dawana.

The 1946 season found Marchildon fit and ready to pitch. Pitching for a bad team, he compiled a 13-16 record. His fastball still had some zip, although it wasn’t the devastating pitch it had been before the war, and by mixing in a good curve and occasional forkball he was quite effective. He had an earned run average of 3.49-not bad for someone who one year ago was in a prisoner of war camp. The next year was even better. The Athletics had added Eddie Joost and Ferris Fain to their roster and improved. Marchildon had a great year, winning 19 and losing 9 with an earned run average of 3.22.

The biggest thrill, and nearly the most disheartening day, for Marchildon came on August 26, 1947, against the Cleveland Indians. Phil was spinning a perfect game with two out in the eighth inning when Ken Keltner came to bat. Keltner, a tough out, worked Marchildon to a full count. On the next pitch Marchildon hummed a fastball that he felt had caught a large part of the outside corner. Phil started to walk off the mound but soon saw that home plate umpire Bill McKinley had called it a ball, walking Keltner. Marchildon went wild and ran to the plate. Buddy Rosar was already in deep conversation with McKinley over the merits of the pitch. McKinley stood by his call, and even though he took a lot of abuse from Phil, he did not throw him out of the game. Calming down a bit, Marchildon got Joe Gordon to fly out to Sam Chapman. Sitting on the bench in the dugout, though, Phil became angrier over McKinley’s call. By the time he was back on the mound, he had lost control of his emotions. He struck out Larry Doby to start the ninth but then gave up a single to George Metkovich. Phil felt deflated. Dale Mitchell also singled, sending Metkovich to third. Hank Edwards followed with a sacrifice fly. Now not only had Marchildon lost a perfect game, he also had given up two hits and the tying run. The game went into extra innings.

Phil pitched out of several jams through the tenth and eleventh innings. With two outs in Philadelphia’s top of the twelfth inning Pete Suder singled. It was Marchildon’s turn at bat. Wasting no time, he blasted a ball to deep left center, and Pete Suder sped home with what turned out be the winning run. Phil got the Indians in order in the twelfth and went home with a splendid victory.

Philadelphia made a run at the pennant in 1948, but Marchildon could not produce the way he had in 1947. The nerves that had been shaken by his war experiences caught up with him again and played havoc with his life and his baseball performance. At the beginning of the 1948 season Phil had a 5-2 record and felt that he would have another good year. Warming up one day with Buddy Rosar, he suddenly felt dizzy and numb; looking around the ballpark, he doubted that he belonged there. When he tried to throw another pitch, the ball felt like a lead weight, going barely twenty feet. Rosar ran up to Phil and asked if he was all right. Marchildon said he didn’t know, that he’d never felt that way before. He told Rosar that he was going home. At home with his wife and daughter he felt better. The team doctor said it was just a virus and a return of the dysentery he had as a prisoner of war. But little aches and pains continued to bother him.

He was a disappointing 9-15 that year. The next season was no better as he posted a dismal 0-3 record in seven games and a total of sixteen innings. At the end of spring training in 1950 he was sold to Buffalo of the International League. At Buffalo he lost five games and was released. Catching on with the Boston Red Sox, he was dropped after one bad relief appearance. He wound up his career in 1951 with Toronto of the International League and was released.

Phil returned to his hometown in Canada utterly depressed, bitter about what the war had done to him psychologically and how it had shortened a promising career in baseball.

Life after baseball was tough. Having lost confidence in himself, he sat around the house brooding and drinking beer. Friends would get him job interviews, but he would not show up. It was difficult going from being a big leaguer to just another guy in the crowd. One day a friend brought over an application for a job at an aviation plant. Barely getting himself out of the house, Marchildon went to the interview and got the job as an expediter, the man who makes sure all the parts and materials are on hand. The Canadian government later closed down the plant, but Bob Knight, an old neighbor from Penetang, got him a job at Dominion Metal Wear Industries, a manufacturer of hospital equipment. Phil stayed there until he retired at the age of 65.

An excellent skier, Marchildon spent time on the slopes near his home. He was also an avid reader of mystery novels. Through the help of friends he had found that there was life after baseball

Honors came to the proud Canadian in 1976 when he was elected to the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame. In 1982 he was elected to the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame. On July 1, 1995, celebrated as Canada Day, Phil Marchildon was honored at the Toronto Sky Dome. Throwing out the first ball, he was celebrated as a Canadian hero for his baseball talent and for his bravery in World War II.

Many who participate in any war find little personal peace. Torn bodies, constant explosions, and dreary days spent in prisoner of war camps leave many with memories and nightmares they can’t handle. Phil Marchildon experienced such circumstances, and they left their mark on him. Starting a baseball career late in life and then being exposed to the hell of war took its toll on his baseball career and his life after baseball. He was fortunate to have a loving wife and friends who appreciated what he had done for Canada and they helped him overcome his depression to live out his life constructively.

Phil Marchildon died on January 10, 1997, at the age of 83. His daughters Carol and Dawana and grandchildren Kenny, Steven and Lisa survived him. His pitching career was short due to starting late in life, and further curtailed by his time in the Royal Canadian Air Force. However, he is to be remembered for his bravery during the war and for overcoming memories that haunted him for a long time. He was one of those who, though not actually destroyed by a shell, was psychologically crushed by the war.

Last revised: February 25, 1947 (ghw)

Sources

BaseballLibrary.Com.

Edwards, Henry P. American League Service Bureau. Released to papers on January 4, 1942. Public Relations Branch of the American League.

Hilligan, Earl J. American League Service Bureau. August 1947. Public Relations Branch of the American League.

James, Bill, and Rob Neyer. The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers: An Historical Compendium of Pitching, Pitchers, and Pitches. New York and London: Simon & Schuster, 2004.

Jordan, David M. “Baseball Goes to War: Phil Marchildon.” Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society. info@Philadelphiaathletics.org

Marchildon, Alain. Web Site, Marchildon Geneology.1997.

Marchildon, Phil, with Brian Kendall. Ace: Phil Marchildon. Toronto: Penguin

Books Canada Ltd., 1993.

Phil Marchildon files at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York.

Full Name

Philip Joseph Marchildon

Born

October 25, 1913 at Penetanguishene, ON (CAN)

Died

January 10, 1997 at Toronto, ON (CAN)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.