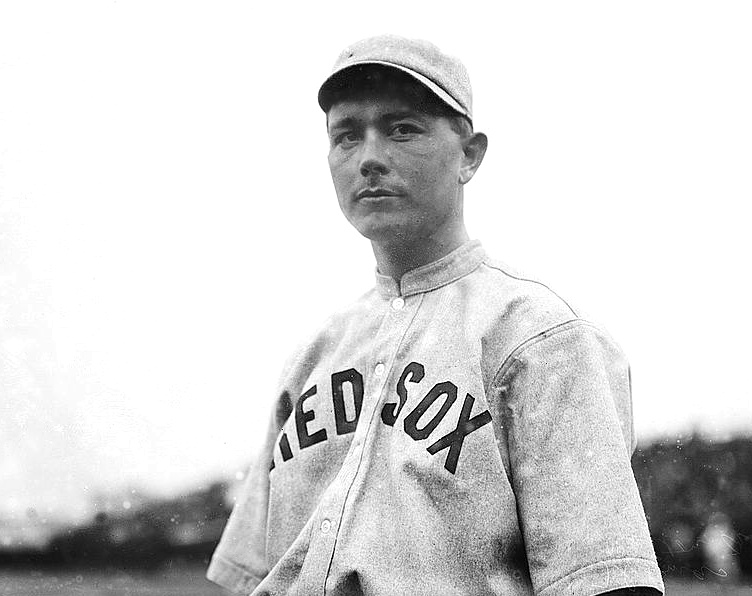

Pinch Thomas

The train pulled out of South Station in Boston on February 18, 1911, heading for Los Angeles and the new location for Red Sox spring training (Redondo Beach, California). Several stops were made along the way as the party picked up players from Western League teams as well as returning veteran players. Manager Patsy Donovan intended to try out at least a dozen of the prospects, hoped to keep a few and farm out other potential players to West Coast clubs for further development. The catchers and first basemen were of particular interest; those positions were where Boston’s roster needed improvement. At a stopover in Chicago, several more veterans and a few Western Leaguers joined the team, and the train rolled on to Kansas City, where four recruits came aboard while a crowd of spectators waited to see Joe Wood make a brief appearance on the platform. Among the four joining the team was Chester David Thomas from Sharon, Kansas. Born on January 24, 1888, in Camp Point, Illinois, he had moved as a youngster with his family to Kansas. Known as Chet, Chess, Chubby Chester, Chatterer Chet, Tom, Thommy, the Golden West Receiver, the Kansan, the Baseball Populist, Goat, and Pinch, the sobriquet that became the enduring nickname among them. Thomas’s brother said he was at a loss as to where it came from. Although Thomas was most frequently called Chet by the Boston scribes, perhaps his record as a pinch-hitter (13-for-31, .419) as a pinch hitter from 1913 to 1918 had all to do with the nickname.

The train pulled out of South Station in Boston on February 18, 1911, heading for Los Angeles and the new location for Red Sox spring training (Redondo Beach, California). Several stops were made along the way as the party picked up players from Western League teams as well as returning veteran players. Manager Patsy Donovan intended to try out at least a dozen of the prospects, hoped to keep a few and farm out other potential players to West Coast clubs for further development. The catchers and first basemen were of particular interest; those positions were where Boston’s roster needed improvement. At a stopover in Chicago, several more veterans and a few Western Leaguers joined the team, and the train rolled on to Kansas City, where four recruits came aboard while a crowd of spectators waited to see Joe Wood make a brief appearance on the platform. Among the four joining the team was Chester David Thomas from Sharon, Kansas. Born on January 24, 1888, in Camp Point, Illinois, he had moved as a youngster with his family to Kansas. Known as Chet, Chess, Chubby Chester, Chatterer Chet, Tom, Thommy, the Golden West Receiver, the Kansan, the Baseball Populist, Goat, and Pinch, the sobriquet that became the enduring nickname among them. Thomas’s brother said he was at a loss as to where it came from. Although Thomas was most frequently called Chet by the Boston scribes, perhaps his record as a pinch-hitter (13-for-31, .419) as a pinch hitter from 1913 to 1918 had all to do with the nickname.

Thomas started playing baseball as an infielder on local grounds in Kansas but found greater opportunities on the West Coast and took up the backstop position with the San Jose team of the California State League in 1908. In 1909 he split his time between Helena, Montana, of the Northwest League and the Oakland Oaks of the Pacific Coast League. The Chicago Cubs secured a 30-day option on Thomas, and not wanting to give him up so soon – he was merely on loan to the Helena club – the Oaks recalled him. At Oakland he was used as a pinch-hitter with great success, and was famous for getting on base by hitting weak but untouchable infield flies and for stopping basestealers.

Thomas began the 1910 season with Oakland, was purchased by the Sacramento team in June, and returned to Oakland on August 1. After a game on August 7, a disagreement erupted between Thomas and fellow Oakland catcher Carl Mitze at a local watering hole. The Oakland Tribune reported that they “went at it hammer and tongs” until spectators stepped in and separated them. Bad blood had existed between the two men, and when Chet started bragging about how he had landed a two-bagger that broke up a game the previous week and he wanted to know why Mitze couldn’t come up with a big hit too. “Oh, I’m there with the big wallop all right,” Mitze countered, as he proceeded to plant a fist on Thomas’ jaw.1 The fight would not be his last and it established his reputation as a loudmouthed scrapper.

Spring training 1911 gave the Red Sox a chance to see what their catcher prospect could do. In the first game, on February 25, Chet Thomas caught the first three innings for the Yannigans. The Boston Globe’s Tim Murnane reported that he “looked awfully good. He shot the ball to second and nailed Wagner by a city block.”2

On March 14, while Chet was out on the town in San Francisco for a night of sightseeing with friends, his baseball career nearly came to an abrupt end when he was beaten by a gang of street thugs. He suffered a serious head injury and doctors feared he’d lose the sight of one eye. Thomas recovered with a just black eye, his sight undamaged, and the Red Sox investment intact. He was sent back to Sacramento for the 1911 season, and his reputation improved as a smart backstop who could pull many a pitcher out of a tough spot. By September 1911 Thomas’s his future as a member of the Boston Red Sox was set.

In 1912 the Red Sox ended their dalliance with Redondo Beach and returned to Hot Springs, Arkansas, for spring training. Thomas arrived on March 7 along with another new catcher, Hick Cady. They joined veteran Bill Carrigan and Les Nunamaker, the 1911 rookie catcher. At first, neither Thomas nor Cady got a chance to show much behind the plate as there were few attempts at basestealing, but Thomas eventually demonstrated his skill at pegging out runners at second and showed strong at-bats, all done with banter and bluster. Paul Shannon of the Boston Post wrote that Thomas had an easy way of shooting the ball to the basemen with time to spare.

Although Thomas’s official debut with the Red Sox took place on April 24, 1912, his first appearance at the new Fenway Park was on April 9, 1912 in the first game ever played at the ballpark– against Harvard College. Thomas raised a few eyebrows when he appeared behind the plate wearing a pair of new-fangled shinguards adjustable without the use of leather straps.

Les Nunamaker appeared in 35 games, Thomas appeared in 13 (eight as a catcher), Hick Cady caught 43, and Bill Carrigan dominated in 87 games. Carrigan, the dean of Red Sox catchers, had a theory endorsed by management that catchers and pitchers worked best in set pairs. Thomas spent his time warming up pitchers, caught when Cady and Carrigan were overworked – which was not often – and filled in as a pinch-hitter. His April 24 debut was against Walter Johnson, as a pinch-hitter for Carrigan in the ninth inning, and he was thrown out at first.

Despite his infrequent appearances in 1912 (and none at all in the World Series, which Boston won over the New York Giants), Thomas earned a portion of the World Series money. He had been signed for two years and although 1912 was a year for breaking in, the Boston Evening Record predicted that Pinch would “make good with a vengeance” once he was allowed more work.3 Thomas spent the offseason working on his farm in Medicine Lodge, Kansas, and arrived in Hot Springs ready for spring training on March 3, 1913. Manager Jake Stahl decided to stay with the four 1912 catchers, and appointed former Red Sox catcher Duke Farrell, an 18-year veteran of the major leagues, to find out “just who’s who and what’s what” with the team’s pitching prospects.4

As the 1913 season began the sportswriters fueled the fans with predictions of a World Series repeat performance, but April was a cruel month for the Red Sox. They lost the home opener 10-9 to the Philadelphia Athletics, a loss blamed on a play by catcher Hick Cady panned as a bonehead move. They lost six of their first eight games as Hick tried to redeem himself. Thomas’s first appearance in a game was on May 3, as a pinch-hitter for Hugh Bedient in the ninth inning of a losing effort against Washington. The Nationals had brought in Walter Johnson to pitch in the eight. Thomas missed three fast ones and dived head-first to the dirt after the third flew by. The invisible missile also passed the Washington catcher, Eddie Ainsmith, and hit the back wall while Pinch ran to first, but he was thrown out before he had made it halfway there. Much to the amusement of the crowd, umpire Tommy Connolly replayed Thomas’s plate pratfall, spinning around as if the ball had merely touched his uniform and brought him crashing down like a ton of bricks.

By midseason the Red Sox bench was a hospital ward with every one of the regulars except Hooper and Speaker out of the lineup at one time or another. By July 16 team President Jim McAleer, frustrated with the way the team’s fortunes were going, replaced manager Jake Stahl with Bill Carrigan. One result of the managerial shakeup meant less time on the bench for Pinch Thomas. By August Chet had improved his average from .189 to .267, and on September 29, the left-handed-hitting catcher hit his first major-league home run, an inside-the-park job at the Polo Grounds in New York off Yankees started Ray Fisher. By the end of the season his average was a respectable .286 in 38 games, 31 as catcher. With no return to the World Series, Thomas returned to his Kansas farm, “where drops of rain are prized like diamonds at certain times of the year.”5 The 1914 Red Sox, extending the trend, had four catchers on the roster: Carrigan, Cady, Nunamaker, and Thomas. The quartet, wrote Tim Murnane in the Globe, seldom got injured and were able to stay in good shape as a consequence of their rotation schedule. Although the backstops were touted as the “finest string of catchers of any club in the country,” the primitive protective equipment, a pitching staff that was considered far below that needed to be competitive in the American League, and the physical impact inherent in the catching position was a constant threat.6 Pinch started occasionally, and often picked up late innings to relieve the exhausted manager, who still preferred to monitor his pitching staff from behind the plate.

For a spell, Thomas himself was among the wounded. In a game in June, the Philadelphia Athletics’ Weldon Wyckoff singled to center and Tris Speaker threw the ball to home in an attempt to stop Wally Schang at the plate, but the ball hit Pinch in the eye, causing a deep gash. He “dropped as if he had been shot, and it was several minutes before he recovered sufficiently,” wrote Murnane.7 The once “finest string of catchers” was now reduced to just Hick Cady, as Carrigan was also nursing wounds he sustained when he was spiked in a game against the Senators and Les Nunamaker was gone, sold to the Yankees on May 13.

Pinch’s recovery stretched into weeks, but he eventually returned, playing an occasional relief inning until the end of the 1914 season. He posted his worst average with the Red Sox, .192, with nine runs and five runs batted in in 66 games. After the season, trade rumors included one that had Boston sending Thomas and Del Gainer to St. Louis for Browns first baseman and occasional backstop Jack Leary. Browns manager Branch Rickey would have none of it. A Red Sox pitching rookie, George Herman Ruth, who appeared in only five games in 1914, looked as though he’d be a good match for the catcher, who sometimes mixed his plate appearances with fisticuffs.

Bill Carrigan continued the battery joint ventures in 1915, pairing Hick Cady with Dutch Leonard and Ernie Shore, while Pinch Thomas tried his hand catching Ruth and Rube Foster. Carrigan, Cady, and Thomas all tried working with Carl Mays, with mixed results. Mays, an underhand pitcher with no previous major-league experience before arriving at Hot Springs, was a challenge. During a batting practice warm-up on April 9, Thomas stopped a Mays wild pitch, and was fortunate the ball did not hit him in the face after hitting the ground in front of him.

When the season began, Thomas became the everyday catcher while Bill Carrigan looked for ways to move the team out of fifth place. Erratic pitching was a problem and fielding needed improvement, but the catchers were doing well. In mid-June the Red Sox left fifth place behind and were tied with the Detroit Tigers for second. Chet appeared in more games than Cady and Carrigan, handled veteran Joe Wood, endured the wild pitches of Carl Mays and formed a solid partnership with Babe Ruth. Boston whittled away the Chicago White Sox’ lead and on July 18 Boston was ahead in the pennant race. Smoky Joe was magnificent on the mound, wrote Tim Murnane, and praise was heaped upon Chet Thomas, not only for his handling of the pitching staff but also for his most timely and effective hitting. “Too much cannot be said for the superb all-round work of Chester Thomas in the series here,” the scribe wrote from Chicago in July. “There was no department of the position in which he did not outpoint [White Sox catcher Ray] Schalk.”8

Although Thomas had done more catching during the regular season than Cady and Carrigan, before the World Series Murnane wrote that Thomas was a fine catcher when healthy, but that an injury during a game in Cleveland had forced him to cut back, and he was out of shape and had lost his famous ability to throw out basestealers.

Chicago sportswriter Hugh Fullerton, in his pre-Series analysis, acknowledged Thomas’s skill handling left-handed pitchers and his ability to prevent stolen bases – although his throwing was occasionally erratic – and considered Boston to be in a comfortable position since the Red Sox pitching staff kept runners to a minimum. The Red Sox defeated the Philadelphia Phillies, four games to one, for Boston’s third World Series championship.

In 1916, despite preseason trade rumors that had Thomas going to Cleveland along with Joe Wood and Ray Collins, Chet was ready to work for Boston, and he did not want to start on the wrong foot. When assigned his room at the Copley Square Hotel, he was handed a key to Room 23. At the time, the number of 23 had a negative connotation along the lines of being forced by someone to leave quickly. Chet complained to Tillie Walker, “What do you think of that. Giving me Room 23. Gee whiz, the season hasn’t opened yet and he’s trying to start me with 23! Not on your life.” He demanded a different room from the desk clerk.9

During spring training catcher Sam Agnew, acquired from the St. Louis Browns, received more attention than Chet, but by May Carrigan reconsidered partnering Agnew with Babe Ruth. During a game in May against Washington, the Babe walked nine batters, three in the eighth inning alone, and Carrigan concluded that Sam was the wrong guy to handle Babe’s curves. Pinch returned to the lineup when Babe was pitching. “The wonderful form of George Ruth may be justifiably traced to Thomas,” wrote a Boston sports scribe. “He has coached the Baltimorean ever since they mobilized at the ramparts in Hot Springs. Ruth has become accustomed to look to Chubby Chester for advice.”10

Pinch continued to pull an occasional boner, causing Carrigan to reconsider catching Ruth himself. The Babe wasn’t having an impressive start in 1916, either, for by mid-May he hadn’t yet hit a home run. Chet caught basestealer Ty Cobb twice in one game in May. By his own count he figured that he stopped Cobb 10 times in 1916 and missed just twice, the best record of any catcher in the American League.11 He was working harder than ever to earn back his place as the primary backstop, and his hitting was improving, too. Carrigan had also tried Thomas with Ernie Shore, the emery-ball hurler, but the relationship broke down. In June Thomas and Shore had a ninth-inning argument, Chet accusing “Emery” of crossing him up. The Shore-Thomas battery would never be the same.

The 1916 season was Chet’s best year in baseball. Along with his partnership with the Babe, he also caught the frequently erratic Carl Mays, already earning a reputation for beanballs, and was credited with handling Mays as well as anyone could. When not in the lineup, he warmed up the pitchers before games, or was on the coaching lines “making as much noise as ‘Sea Lion’ Charlie Hall used to do.”

In August Pinch’s reputation as a fighter emerged again when he swapped punches with Browns third baseman Jimmy Austin, who had accused the Red Sox’ Rube Foster of trying to bean him. Pinch called Jimmy yellow, told him to stand up and strike out. Austin missed the next pitch, Chet added more insults, and Jimmy took a swing at Chet’s head, catching him on the side of the face. Pinch responded with three punches to Jimmy’s face, and Austin’s return shot hit umpire Ollie Chill instead of Chet. Thomas and Austin were both suspended indefinitely, public outrage erupted about violence on the baseball diamond, and Red Sox President James Lannin issued a statement defending Thomas’s actions: “Had Thomas not gone after Austin and fought back I would have fined him for his lack of aggression.”12 A few days later Thomas was back in the lineup.

The 1916 World Series win – the Red Sox defeated the Brooklyn Robins four games to one – capped Boston’s fourth championship season, and Bill Carrigan announced his retirement from baseball. A gang of players, including the Babe, Pinch, Jack Barry, Tillie Walker, and a few others celebrated Boston’s fourth championship with a hunting trip to Lake Squam in New Hampshire, a gift from the Draper-Maynard Company. Besides duck hunting, the outing included a boxing match between Ruth and first baseman Doc Hoblitzel refereed by Pinch, who wisely ruled the match a draw.13

Chet Thomas liked playing in Chicago, and the reason became clear when he secretly wed cabaret dancer, Doxie Emmerson-Love on December 23, 1916. The Chicago Tribune reported the details of the romance and the wedding held at City Hall, while the Boston Globe printed just a brief announcement. A native of San Francisco, Doxie had caught the eye of the Boston backstop and he had returned to the Central Inn on Wabash Avenue every time he was in town over the previous two baseball seasons. With the 1916 season over, Chet had returned to his farm in Medicine Lodge, Kansas, but, finding it lonesome on the prairie in mid-December, boarded a train for Chicago and proposed to Doxie. She accepted, vowing also to abandon the Chicago café scene and move to Medicine Lodge to become a farmer’s wife. “The people in this café don’t know I’m going to quit dancing and go away out west and live with the cows and chickens,” said Mrs. Thomas just after finishing an exhibition of her art, “but I know I’m going to like the new life.”

For his part, Chet said, “The folks down in Kansas don’t know anything about this, but I know it will be all right with them after they see her.”14

Doxie was a devoted baseball wife, accompanying Chet to spring training in Hot Springs in March 1917. She went horseback riding with Helen Ruth, and after practice was over the wives joined their husbands on Ozark mountain hikes. Doxie was just beginning to learn more about her husband and his multifaceted baseball job. When Chet was on the coaching line at first base his verbal outbursts might have shocked her if she had not sat far away behind the dugout. Chet would spit on his hands and call on all the Roman gods to witness the base hit that was soon to occur, shout encouragement to the Boston baserunners, and harass the opposing first sacker. That first year of their marriage, she stayed in Boston at their apartment in the Fenway area and often attended games. On May 24, 1917, with the US having joined in the Great War, Pinch Thomas registered for the draft as the law of the land required. He was exempt from serving due to his marital status.

Jack Barry was the new manager and Harry Frazee was the new owner of the team in 1917. Although Chet had had a successful year in 1916, appearing in 99 games with 216 at-bats and hitting .264, another year brought new challenges and competition. His average in 1917 dropped to .238 in 83 games played, but he was the best catcher the Red Sox had, and he was still Babe Ruth’s preferred batterymate. By the end of their partnership, Pinch Thomas had caught 68 of Babe Ruth’s 144 Red Sox starts, including 10 of his 17 shutouts. Sam Agnew was next with 24 starts.

Ed Martin of the Boston Daily Globe called the game against the Washington Senators at Fenway Park on June 23, 1917, the best pitching seen in Boston since 1904. Ruth was the starting pitcher, Thomas was his catcher. The first Washington batter, second baseman Ray Morgan, received four balls, according to umpire Brick Owens. Ruth accused Owens of missing the call on two of them, and a verbal battle erupted between pitcher and umpire as the Babe charged home plate. Pinch Thomas placed himself between the outraged pitcher and his intended target, but Babe, swinging with both hands, caught Brick behind the left ear. Manager Barry and several policemen dragged Ruth off the field as Ernie Shore stepped up on the mound and warmed up. Agnew replaced Thomas behind home plate. Ernie Shore went on to a “no-hit, no-man-reach-first” (for Shore, at least) game. Shore confessed that he did not know he had achieved the feat until Thomas rushed up to him and shook his hand after the last out. “I was wondering what the occasion was,” Shore said sheepishly. “Chet told me and then I realized the one ambition of my baseball career. I have always wanted to turn in a no-hit game but have just missed it.”15

After the 1917 season Thomas spent the winter in California. Back in Boston, trade talks between the Red Sox and the Philadelphia Athletics brewed up a deal that brought Joe Bush, Amos Strunk, and catcher Wally Schang to Boston and gave Vean Gregg, rookie outfielder Merline “Officer” Kopp, Chet Thomas, and $60,000 to Connie Mack. The deal was considered a coup for Boston and a terrific blow to the Athletics, amid predictions that it paved the way for Boston to win the 1918 pennant. Stuffy McInnis said he hoped Pinch would help the Athletics, “for he is very capable as far as the mechanical end of the game goes and particularly good for head work. He’ll find Connie a great fellow to work for and I know he’ll give his best from the start.”16

But it didn’t turn out that way. Thomas, devastated by the trade, blamed the sports reporters for deflating his worth. At spring training in March, he considered quitting baseball and said he had been working during the offseason for a movie company in California. He did not want to report to Philadelphia, and his relationship with Connie Mack deteriorated when he demanded more money than Mack considered reasonable. In Mack’s opinion, Chet’s reputation had been inflated by the pitchers he worked with.17 Chet figured he could not have been such a detriment to the team as some writers said. As for the pitchers shoring him up, he claimed Babe Ruth would have been traded or released by Bill Carrigan if it had not been for him, and that he had broken in most of the other pitchers on the Red Sox team. All he wanted was to retire from baseball with everyone’s goodwill.18

Thomas played no games with the Athletics. In June he was sold to the Cleveland Indians but spent two months in California with the movie company. He joined the team in August and appeared in 32 games, 24 of them as a catcher, and also was employed as the third-base coach. Along the sidelines his role as the “bull-throated barker” was credited with winning games for the Indians as Chet kept up streams of verbal harassment that drove opposing pitchers off the mound and knocked fielders off-kilter.19 Indians manager Lee Fohl used Pinch as a pinch-hitter11 times and he delivered on five occasions, finishing the season with a pinch-hitting average of .454. At the end of the season he returned to his purchasing department job with the California movie company.

Pinch returned to Cleveland in 1919 and caught 21 games, appearing in 34 overall. His legendary reputation on the third-base line followed him back to Philadelphia, where the newspapers complained about his antics, calling him a rank nuisance. In 1920 Thomas filled in as manager of the team while Tris Speaker accompanied the body of Ray Chapman home. His time presiding behind the plate decreased sharply; he caught in just nine games and spent more time on the coaching line, where his errorless judgment was said to have preserved many a baserunner and his verbal outbursts continued to be an opposing pitcher’s nightmare. In 1921 he appeared in 21 games, his last on June 19. By then his attention was focused on Los Angeles and the movie business, where he had secured a job as an assistant director.

In 1928 Thomas appeared in the movie Warming Up with baseball players Mike Donlin and Truck Hannah. What became of his life subsequently is open to speculation. Chet and Doxie were divorced, she went back to Kansas with their son, and in 1930, Chet was living in a rooming house in Modesto, California. In 1936 the American League president received the following letter:

Mr. William Harridge,

On April 22 you presented lifetime passes to a number of old ball players. Among these was the name of Chet Thomas of Sharon, Kansas. I am Chet Thomas’s son. My dad is in a state hospital and will never be able to use this pass. I would like to have the pass as a keepsake. Could it be possible for me to get it? Or have you sent it to Kansas. As I have already told you he is not in Kansas. Any information you could send me on the matter would be appreciated.

Yours truly,

Chester Frank Thomas20

Pinch Thomas died at the Modesto State Hospital in California on December 24, 1953. The cause of death was listed as pulmonary edema, amputation of the left leg above the knee due to arteriosclerosis, recurrent infection, gangrene, and peripheral vascular disease with the contributory, unrelated condition of psychosis. He is rarely mentioned among catchers, coaches, or other memorable characters. Chet Thomas’ greatest defender and booster was himself and once gone he faded into part of the hidden history of baseball, only to appear from time to time attached to another’s story. Let it be less so now.

Notes

1 Oakland Tribune, August 9, 1910

2 Boston Globe, February 26, 1911.

3 Boston Evening Record, September 26, 1912.

4 Boston American, March 4, 1913.

5 Sporting Life, May 16, 1914

6 Boston Daily Globe, April 12, 1914

7 Boston Daily Globe, June 3, 1914

8 Boston Daily Globe, July 21, 1915

9 Boston Daily Globe, April 10, 1916

10 Boston Evening Record, June 30, 1916

11 Boston American, March 11, 1917

12 Boston American, August 20, 1916

13 Baseball Magazine, 1916, p. 98

14 Chicago Tribune, December 24, 1916

15 Boston Traveler, June 25, 1917

16 Boston Traveler, December 15, 1917

17 Eau Claire (WI) Leader, April 4, 1918

18 Hall of Fame player file for C.D. Thomas. April 18, 1918

19 Washington Post, August 24, 1918

20 Hall of Fame player file for C.D. Thomas. Letter dated May 4, 1936.

Full Name

Chester David Thomas

Born

January 24, 1888 at Camp Point, IL (USA)

Died

December 24, 1953 at Modesto, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.