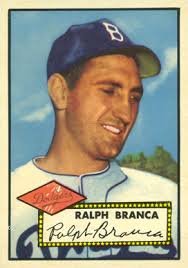

Ralph Branca

Ralph Theodore Joseph Branca was a New York guy. He was born on January 6, 1926, in Mount Vernon, just outside New York City, as the fifteenth of seventeen children. His middle name was a celebration of the first President Roosevelt, who also hailed from the Empire State.1 His elementary and high school years were spent in Mount Vernon. He attended New York University, where he also played basketball, and was signed by the Dodgers after a local tryout camp.2

Ralph Theodore Joseph Branca was a New York guy. He was born on January 6, 1926, in Mount Vernon, just outside New York City, as the fifteenth of seventeen children. His middle name was a celebration of the first President Roosevelt, who also hailed from the Empire State.1 His elementary and high school years were spent in Mount Vernon. He attended New York University, where he also played basketball, and was signed by the Dodgers after a local tryout camp.2

Branca’s father, John Branca, came to America from Italy as a child with his family in 1888. Ralph was named after his grandfather, Raffaele, who took the name Ralph in the United States. Ralph’s mother was Katherine Berger, who was born in Hungary. Katherine and John married on October 17, 1902. At various times, John was a trolley conductor, a machinist, and a barber.3

Ralph married Ann Mulvey in 1951. She was a New York girl from a prominent family. Her parents, James and Dearie Mulvey, owned a share of the Dodgers and her maternal grandfather, Steve McKeever, had been president of the Brooklyn club.4 At the end of his playing career Branca was offered an opportunity to stay in baseball as a pitching coach for Los Angeles in the Pacific Coast League, “But I just didn’t want to go to California,” he said in a 2008 interview.

Instead, Branca became a financial executive in and around New York City, work he found satisfying. “When you can hand somebody a check for $300,000 in 1961 based on a life insurance policy her husband had purchased from me, you feel good. You feel like you’ve had a positive effect on that person’s life.” He later combined his baseball prominence, his financial acumen, and his desire to help others when he ran the Manhattan-based Baseball Assistance Team (BAT) for seventeen years, an organization formed to help those who had had careers in baseball but were facing difficult financial circumstances in their post-baseball lives.5 His daughter Mary married former New York Mets manager Bobby Valentine in 1977, and his other daughter, Patricia, also made a life in New York.

As a Brooklyn Dodger, the 6-foot-3, 220-pound right-hander was involved in two of the biggest moments in baseball history, which were also prominent moments in the fabric of American culture. One was the integration of baseball by Jackie Robinson in 1947, and the other was as the man who threw the pitch hit for a home run by Bobby Thomson that won the 1951 National League pennant for the New York Giants. In 1947 the 21-year-old Branca became the second youngest National Leaguer to win twenty games.6

The Brooklyn club signed Branca out of New York University in 1943, when he was just 17 years old. He had played both baseball and basketball for NYU. The Dodgers sent him to Olean (New York) their affiliate in the Class D Pennsylvania-Ontario-New York League, where he split ten decisions. Branca was promoted to the Montreal Royals of the International League, Brooklyn’s top farm team, in 1944. He had a 4-5 record for the Royals, when the Dodgers called him up on June 7. Five days later, he made his major-league debut, allowing two hits in three and a third innings of a 15–9 loss to the Giants. Branca split the 1945 season between Brooklyn and St. Paul of the American Association, but spent all of 1946 with the Dodgers. He won only three games, but pitched very well in September and was Brooklyn’s starter in Game One of the playoffs against St. Louis. His combined record for his first three seasons with the Dodgers was a mediocre 8-9.

By 1947 the Dodgers were one of the most prominent franchises in baseball. Brooklyn had drawn nearly 1.8 million fans to Ebbets Field in 1946 and would inch over that figure in 1947. The Dodgers had lost a playoff to St. Louis for the 1946 pennant, and were considered a strong contender for the 1947 flag. Their most visible newcomer was Jackie Robinson, the International League’s Most Valuable player in 1946.

“As I look back, I’m proud that I was tight with Jackie,” Branca said. “He was a great competitor and a great teammate. The timing of bringing him to team was perfect. I’ve always been proud that baseball integration beat the government’s integration by seven years and that I was a part of it. My friendship with Jackie continued after baseball. We played golf together and we both worked in Manhattan and saw each other a lot while he was with Chock Full o’ Nuts.”

As Branca saw it, Robinson’s acceptance by the Dodgers was directly related to their recognition of his ability to help the team win. “Some saw it right away, for others, it took until the middle of the year, but by the second half of the season everyone saw it. We all wanted the glory of the World Series, and it was pretty clear we weren’t going to get there without Jack.”

According to Branca, the Southern culture that prevailed in baseball clubhouses at the time was not an issue for the Dodgers. “Once we knew he belonged, it was fine,” he said. The opposition was a different story. “Jackie was helping to beat them, and they were mad.”

The 1947 season was the high point of Branca’s major-league career. His 21 wins, second-best in the league, were nearly a quarter of his lifetime total of 88. He also led the National League in starts and was second in strikeouts and third in earned run average.7 Branca was chosen as an All-Star, but did not appear in the game. He was the starter and loser in Game One of the World Series against the Yankees, and appeared twice more in relief, picking up a win in Game Six.

In 1948 Branca’s win total dropped to 14 and his ERA went up by nearly a run, to 3.51. “I was 12-5 at the [All-Star] break in 1948 [Actually, he was 10-6.]. Then, a couple of my, shall we say, lower IQ teammates, were playing burnout by throwing the ball to each other as hard as they could trying to hurt each other’s hands. One of the throws got away and hit me in the shin. The leg swelled and it turned into an infected bone lining. I spent three weeks in the hospital with periosteomyelitis and only got two wins [actually four] in the second half.”8

According to Branca, the bone infection settled in his shoulder and he could not throw as hard through 1949 and 1950. Nevertheless, he was 13-5 in ’49 and led the league in winning percentage, though his ERA climbed to 4.39.9 By 1950 manager Burt Shotton used him mostly in relief, and Branca remembers that season, in which he went 7-9, as “a waste.” He was little help as the Dodgers lost the pennant to Philadelphia on the last day of the regular season.

As 1951 started, things were looking up for Branca. The Dodgers were in first place for most of the year, and “by throwing in the bullpen every day my arm started to get stronger.” He made his first start that year on May 28, and after throwing a two-hit shutout against the Pirates on August 27, his record was 12-5.

But September and October were difficult for Branca and the Dodgers. He started six games the Dodgers lost, as his record for the season dropped to 13-12.10 The Dodgers had a thirteen-game lead after an August 11 doubleheader and played a little over .500 the rest of the way.11 The Giants, meanwhile, went 37-7 down the stretch, caught the Dodgers on the last weekend, and beat them in a playoff culminated by the famous “Shot Heard ‘Round the World” home run off Branca by Bobby Thomson.12

In January 2001, Joshua Prager, a reporter for the Wall Street Journal, published the details of a sign-stealing scheme the Giants rigged in the Polo Grounds, their home ballpark. The scheme involved a telescope from windows in the center-field clubhouse, a buzzer rigged under dirt in the bullpen, and a reserve catcher positioning his body and equipment to tip off the batter as to which pitch was coming. Prager’s story confirmed for the public what Branca had been told by his Detroit Tigers roommate Ted Gray in 1953. Gray was friends with Giants reserve outfielder Earl Rapp and was told the story. Branca said Thomson knew what was coming on October 3, 1951, and while he still had to hit it, the information was certainly useful.13

“I begrudge the Giants the 1951 pennant,” Branca said emphatically in the 2008 interview. “They deprived our owner of money he deserved, they deprived our fans of the joy of a pennant winner, and they deprived my teammates and me of the fame and glory that comes from playing in the World Series. What the Giants did was despicable. It involved an electronic buzzer. No one else used that. Sometimes you could see people in the center-field scoreboard in Chicago or wherever using towels to give signals and you could do something about it. The buzzer was undetectable, and it was wrong.”

Branca kept the story essentially to himself until Prager’s article appeared.14 He appeared with Thomson on television and at autograph shows, and generally played the role of good sport for half a century. The two ex-players thrown together by fate became close friends; a friendship that Branca said became strained after Prager’s public exposure of the Giants’ scheme.15

The sign-stealing revelations and the reactions to those revelations “affected my relationship with Bob. We’re not as close. We haven’t done a card show in two years, and we don’t talk as often,” Branca said. “Part of that might be that he moved down South,” Branca allowed. “He was one of the soldiers; he wasn’t one of the leaders. Still, he okayed it, and he used it.”

Branca said he was especially disappointed in Giants captain Alvin Dark and former teammate Eddie Stanky. An observant Catholic, Branca said he took umbrage because Dark and Stanky claimed to be very religious. Most of his vitriol, though, was aimed at Giants owner Horace Stoneham, manager Leo Durocher, and coach Herman Franks, the man in the clubhouse with the telescope. “They were the generals,” Branca said.

Thomson’s home run, regardless of the circumstances, was the beginning of a steep downhill slide in Branca’s baseball career. In spring training of 1952 he fell off a chair while playing Monopoly in the clubhouse and landed on a Coke bottle.16 Branca said that threw his back out of alignment, a situation that still plagued him a half-century later. “Our trainer was an osteopath, which was basically a chiropractor with two years of medical school, and he didn’t think to check my alignment,” sighed Branca. “Using a lift might have helped me then.” In later years, Branca turned to using lifts in his shoes to cope with the effects of his 1952 accident.

As it was, Branca appeared in only 16 games for the 1952 Dodgers, none in a World Series loss to the Yankees. On July 10, 1953 the American League’s last-place Detroit Tigers claimed him after he was waived out of the National League.17 “The Detroit trainer worked hard on me, but he didn’t check my alignment either,” Branca remembered. “The state of sports medicine was nothing like it is today.” Branca went 7-10 in thirty-four games over parts of two seasons with the Tigers before receiving his release in July 1954.18

Later in 1954, Branca called the Yankees to pitch batting practice. Manager Casey Stengel and pitching coach Jim Turner were impressed enough to activate him, and he went 1-0 in five games.19 Branca went to spring training in 1955 with the Minneapolis Millers, the top minor league affiliate of the Giants. He hurt his arm while pitching nine innings in a spring training game, but said he didn’t tell the trainer. Millers manager Bill Rigney let Branca go when he was ineffective in subsequent outings.

Thinking his career was over, Branca said, he accepted an invitation to Old Timers Day at Yankee Stadium in 1956, and discovered while preparing for that game that his velocity had returned. He contacted Dodgers general manager Buzzie Bavasi, and spent the last month of the 1956 season with Brooklyn. He made one appearance, on September 7, and in two innings allowed one hit and two walks and struck out two.20

Branca accompanied the team on its postseason tour of Japan and hurt his arm again — he said manager Walter Alston did not allow him sufficient time to warm up before a relief appearance. The Dodgers invited him to spring training in 1957, but he failed to make the team. The Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League offered Branca a coaching job that he turned down, ending his baseball career.

While Branca seemed to harbor some bitterness over how his career ended, Bavasi said in 2006 that he did not intend for Branca to pitch much in his last stint with the team. “I brought him in not to pitch, but in order for him to retire as a Dodger,” Buzzie said. It seems that the team and the player were not on the same page regarding expectations, or that time had clouded memories.

Ralph and his wife Ann lived in the same country club community in Rye, New York, since the middle 1960s. Branca sang publicly and earned praise for his strong baritone. He was also a devoted poet and held the record for 17 consecutive wins on the television game show Concentration.21 He was personally and financially successful, and was one of the most famous baseball players of his era, even if he felt his pitching potential was largely unrealized due to a series of negative circumstances. He was through as a ballplayer as he turned 30, but in his decade in the big leagues, he bore witness and directly participated in two of the most famous baseball events of the twentieth century.

Branca died at the age of 90 on November 23, 2016.

Sources

All quotes by Ralph Branca are from an interview with the author on September 29, 2008; quotes from Buzzie Bavasi are from an e-mail exchange on October 26, 2006.

Notes

1. Joshua Prager, The Echoing Green, New York: Pantheon Books, 2006: p. 118.

2. Joshua Prager, The Echoing Green, New York: Pantheon Books, 2006: p. 127.

3. ancestry.com, US Census (1910, 1920, 1930).

4. Bob McGee, The Greatest Ballpark Ever. Piscataway, New Jersey: Rivergate Books, 2005: p. 120.

5. Jon Heyman, Sports Illustrated, October 3, 2006.

6. Christy Mathewson was several months younger than Branca when he won 20 games for the 1901 New York Giants. Since then, Dwight Gooden, with the 1985 Mets, became the youngest ever to win 20 games.

7. Macmillan Baseball Encyclopedia: p. 1846.

8. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery does not list periosteomyelitis. Branca’s disorder may have been osteomyelitis.

9. Retrosheet

10. Ibid

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Jon Heyman, Sports Illustrated, October 3, 2006.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. Baseball-reference

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. Jon Heyman, Sports Illustrated, October 3, 2006.

Full Name

Ralph Theodore Joseph Branca

Born

January 6, 1926 at Mount Vernon, NY (USA)

Died

November 23, 2016 at Rye, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.