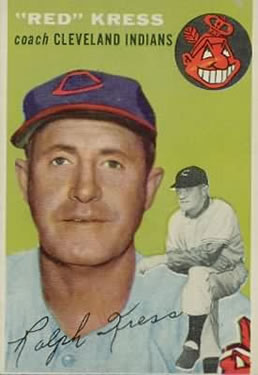

Red Kress

On July 27, 1955, the players and staff of the Cleveland Indians presented a brand-new $3,000 Oldsmobile to coach Red Kress for his untiring work with the team. The Indians’ third baseman, Al Rosen. summed it up by saying that the team wanted to do something for Red to pay him back for all he had done for the team. Casey Stengel, his boss on the 1962 New York Mets, called Kress “the hardest working man I ever knew,” adding that he never asked anything of the players that he didn’t demand of himself. Kress’s ability to throw long sessions of batting practice every day was legendary. An infielder by trade, Kress was no slouch on the mound. A speed meter used in 1939 recorded him throwing at 139 feet per second (about 96 miles per hour). Kress professed to having never had a sore arm. He even quipped that “Satchel Paige couldn’t make that claim.”[fn]The Sporting News, March 21,1956[/fn] Kress’s pitching notoriety was such that during spring training of 1953 The Sporting News mentioned that “the Tribe’s human pitching machine needed oiling after he tore some skin off his forefinger.”

On July 27, 1955, the players and staff of the Cleveland Indians presented a brand-new $3,000 Oldsmobile to coach Red Kress for his untiring work with the team. The Indians’ third baseman, Al Rosen. summed it up by saying that the team wanted to do something for Red to pay him back for all he had done for the team. Casey Stengel, his boss on the 1962 New York Mets, called Kress “the hardest working man I ever knew,” adding that he never asked anything of the players that he didn’t demand of himself. Kress’s ability to throw long sessions of batting practice every day was legendary. An infielder by trade, Kress was no slouch on the mound. A speed meter used in 1939 recorded him throwing at 139 feet per second (about 96 miles per hour). Kress professed to having never had a sore arm. He even quipped that “Satchel Paige couldn’t make that claim.”[fn]The Sporting News, March 21,1956[/fn] Kress’s pitching notoriety was such that during spring training of 1953 The Sporting News mentioned that “the Tribe’s human pitching machine needed oiling after he tore some skin off his forefinger.”

According to some baseball records, Ralph Kress was born on January 2, 1905, in Columbia, California. But a search of the Oakland Tribune showed him playing high-school basketball in February of 1925 and on the football team in September 1925, which could explain why the 1968 Macmillan Encyclopedia listed the year of his birth as 1907. His parents, Edward and Dora (Meuses) Kress, were born in California in 1865 and 1871 respectively, and married in 1888. The Kress name is German/Irish, but there are indications in census records that the family was originally from France and may have emigrated to Canada and then to the US. This may allude to Dora’s father, who was born in Canada and moved to California. Red was one of nine children and grew up in Columbia, Tuolumne, and finally Oakland as the family slowly moved west across California after Edward Kress died in a quarry accident.

Kress made a name for himself playing on the Oakland sandlots and at Berkeley High School. He was “discovered” playing for the Barrel House team in the Standard Oil Twilight League by a scout named C.C. Chapman and signed with the St. Louis Browns on December 28, 1926, beginning a lifelong career in professional baseball that ended only with his death on November 29, 1962. In a 1956 interview in The Sporting News, Kress mentioned that “I never laid off a single winter. If I wasn’t playing or managing winter ball in South America, I’d play, manage, or coach some team in California.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

The Browns farmed Kress out to Tulsa in the Western League for the 1927 season. The Western League was pretty fast company for a rookie, and Red found himself on a team loaded with talent. He was installed as the shortstop and played every game, hitting .330. When Tulsa’s season concluded, the Browns called him up for a quick look. Kress made an inauspicious debut, in Washington on September 24. The first ball hit to him was a slow roller and he threw wildly to second base trying for a force. At bat he flied out his first time up, but later singled. The Browns were impressed with Kress and took him to spring training in West Palm Beach, Florida, in 1928. Kress hurt his ankle in an exhibition that kept him on the bench until the fifth game of the season, the Browns’ home opener against Detroit. He went 2-for-2 with a double in the loss. He didn’t miss a game for the rest of the season. At bat he hit .273 and drove in 81 runs for the third-place Browns.

Kress improved in nearly every category in 1929. He was third among shortstops in chances per game and led the league with a .946 fielding average and 94 double plays. At the plate his average jumped to .305 and he led the team with nine home runs and 107 RBIs. Over the winter, management allowed him to name his price and he signed for $7,000. In 1930 Kress upped his batting average to .313 with 16 home runs and increased his RBIs to 112. He led the league playing in 154 games, but his fielding fell off from 1929; he led the league in errors at shortstop. (Kress played 31 games at third base as the Browns looked at Jim Levey as a shortstop.) Despite the growing Depression, the Browns raised his pay for 1931 to $9,000, with some bonus clauses. Red picked up some extra cash in the fall of 1930 touring with the Lefty Grove All-Stars. On October 29 the major leaguers played the Royal Giants, a team of black players in the California winter league featuring Mule Suttles, Biz Mackey, and Willie Wells. Grove’s team won 6-3, after Kress lashed a bases-loaded single in the first to help the All-Stars jump out to a lead they never relinquished.

In 1931, the Browns turned shortstop over to Levey. That marked the beginning of Kress’s life as a jack of all trades. He saw action in 84 games at third base, but he also played shortstop, first base, and the outfield. The unsettled job situation did not seem to affect his hitting; he batted .311 and drove in 114 runs while hitting 16 home runs again. After the season he married Lucille Baker in Tulsa in a double wedding with Lin Storti, a former teammate at Tulsa. After the ceremony Kress departed for a cross-country barnstorming trip with Earle Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics. Then he and Lucille set up residence in the San Francisco Bay area. The couple had one child, a daughter, Lila.

The Depression was worsening, the Browns had finished in the second division again, and the team sent Kress and other players contracts calling for pay cuts; they wanted to cut Kress from $9,000 to $7,000. Kress became a holdout. He proposed that the two sides compromise at $8,000.The team agreed on an $8,000 offer, but said it was good for just one day and would then drop by $500 a day. Kress’s reply was printed in the March 25 St. Louis Post-Dispatch: “I sure have lots to be swell-headed about working for the Browns for a measly $8,000. … Will leave here Saturday, need expense money for wife and myself. …”[fn]St. Louis Post Dispatch, March 25, 1932[/fn] Owner Phil Ball was not amused and made sure his final telegram was printed in the paper, saying in essence that Kress had an inflated opinion of his ability and that the club did not need his as much as he might think. Kress signed for $8,000, reported to spring training, and won the starting job at third base, but his days in St. Louis were numbered. On April 25 he was traded to the Chicago White Sox for pitcher Bump Hadley and outfielder Bruce Campbell. The 1932 White Sox were a weaker squad than the Browns and welcomed Kress’s bat, but because of young shortstop Luke Appling, Red saw the most action in the outfield. He did lead the Sox in homers with nine.

The 1933 White Sox underwent a major overhaul. Kress took over at first base and the entire outfield was replaced. Kress struggled at the plate, hitting only.248. The 1934 White Sox were worse. Kress was benched and then swapped to Washington for infielder Bob Boken. The Senators’ shortstop was manager Joe Cronin, so Kress was assured of being a utility player. He saw action at five positions until mid-August when he broke his thumb in a practice session pitching to Heinie Manush for a movie, Batter Up. Kress was done for the season. His average with Washington was a dismal .228.

Kress’s fortunes improved somewhat in 1935, which included a remarkable reprieve from demotion to the minors. He spent the first half of the season as a pinch-hitter and occasional outfielder or first baseman. (He even came in as a mop-up pitcher in three games.) In late July Kress was hitting .140 and was about to be sent to the minors, but suddenly injuries struck the Senators and Kress was given a start on July 24. The Senators lost but he smacked four hits and found himself back in the lineup for good, even working his way into the cleanup spot. He ended the season with a .298 average. After the season Kress joined Earle Mack on a barnstorming trip to North Dakota, Montana, and British Columbia.

The 1936 Senators had Cecil Travis and Buddy Lewis in the infield so Kress served as a backup. He was in the lineup on July 19 in Washington when the Indians were visiting. Kress played in 109 games and hit .284. Over the winter there was speculation that he would become the manager at Chattanooga, a Senators farm club in the Southern Association. Instead, on January 29, 1937, he was sent to Minneapolis in the American Association along with another player and cash for first baseman/outfielder Jimmy Wasdell. Given the starting shortstop job, the 32-year-old Kress had a strong season. Minneapolis was in the pennant chase the whole season. Kress hit .334, clubbed 27 homers, and had 157 RBIs. In the field he led the league in errors, but also in chances per game. Correspondents for The Sporting News who covered the American Association named him the league’s most valuable player.

Minneapolis sold off its veteran players after the season. Kress and pitcher Charley Wagner were sent to the Boston Red Sox for about $50,000 and four players. Then the Red Sox sent him to the Browns with outfielder Buster Mills and pitcher Bobo Newsom for pitcher Joe Vosmik. While these deals were being made, Kress was in California playing for the Pasadena Merchants in the California Winter League. In March he served as a coach and player for the Bellingham, Washington, squad. Bellingham was a farm club of the Hollywood Stars and Kress had been asked to help with exhibition games.

At St. Louis Kress became the everyday shortstop, and had a fine season. He hit .302 and led the league shortstops with a .965 fielding average. In March 1939 he staged a brief holdout before joining the team for spring training. He started the season at shortstop but on May 13 was traded to the Detroit Tigers in a ten-player deal precipitated by a fiery confrontation between Bobo Newsom and manager Fred Haney. Kress stepped into the shortstop position for the Tigers and had early success but slumped at bat and finished with a .242 average. That winter he played for Hollywood in the California Winter League. For 1940 the Tigers signed him to a player’s contract with the agreement that he would also coach at first base. The 1940 Tigers were a veteran crew and Kress saw limited action, batting 99 times with a .222 average before becoming a full-time coach on August 1. After a spirited stretch drive the Tigers won the pennant, then lost the World Series to Cincinnati in seven games. The day after the Series ended, the Tigers released Kress, who was surprised because, he asserted, general manager Jack Zeller had talked him out of taking the manager’s job with Hollywood the previous offseason and told him the team had plans for him after he was through playing.

After his release, Kress was named player-manager of the St. Paul Saints in the American Association. He saw action in 118 games and hit .293 with 10 homers, but the Saints finished seventh and he was fired. He then signed to play and coach for league rival Louisville. He played in 119 games, including six as a relief pitcher, and hit .249. After the season the Colonels traded him to Toronto of the International League, where in 1943 he served as a utilityman and coach. He pitched in 15 games, with a 3-2 record, and hit 266 in 169 at-bats as the Maple Leafs won the pennant but fell to Syracuse in the final round of the playoffs. Kress returned to Toronto in 1944 and played in 70 games, 12 as a pitcher. He batted .259 and had a 2-6 record. Manager Burleigh Grimes and Kress were fired at the end of the season.

In 1945 the well-traveled Kress joined the Baltimore Orioles as a player/coach. With the ranks of ballplayers depleted by World War II, he played in 85 games, including 19 as a pitcher (nine starts, eight of them complete games). He played every position except catcher. On April 22 he was in the outfield for a doubleheader against Buffalo, made a sparkling catch, and threw a runner out at second. At bat he collected two home runs, two doubles, a triple, and a single with four RBIs. In the Governor’s Cup playoffs, he started a game against Montreal and lost 1-0 on a ninth-inning error. In 1946 he was a coach for the New York Giants. With the team’s pitching staff beset by injuries, Kress even pitched in relief, on July 17, giving up five runs in 3⅔ innings. It was his final appearance in a major-league game. He ended his pitching career with a 12.57 ERA and wins or losses. At the plate, he ended with a .286 average in 5,087 at-bats. Red settled in as the first-base coach for the Giants, until he was released after the 1949 season.

In October Kress was hired to manage the Sacramento Solons in 1950. That winter he managed Rosabell in the California Winter League. The Solons met in Anaheim for spring training. Sacramento was short on talent and the scribes picked them to finish in the second division. Red was tough on the squad from the opening bell. He told the players that no one was guaranteed a job. The first day’s practice lasted four hours. When play began the Solons sank to the bottom of the league. The team’s board of directors gave Red a vote of confidence on May 9, but their confidence ended on June 1. On July 1 Kress was back in the dugout as the manager of Superior in the Northern League. He took over a third-place club and kept it in contention for the rest of the season, finishing five games out. He even put himself into the game as a pitcher on four occasions, tossing 27 innings and going 2-1. In the playoffs Superior beat Eau Claire four games to one, but lost in the finals to Sioux Falls.

Kress was hired to manage El Centro in the Southwest International League in 1951. Pitching trouble started early in the season and Red pressed himself into service as a pitcher. His mound work was so impressive that he was named to the all-star game and came out the winner of an 8-7 game when he tossed five innings and gave up only one run. El Centro fired Kress on July 6 in a cost-cutting move, but he was immediately hired to manage first-place Juarez. Between the two teams Kress played in 35 games, 30 of them as a pitcher. He hit a robust .373 and had a record of 8-6 on the mound. He made eight starts and tossed three complete games. Kress ended his minor league pitching career with a record of 20-23 and an ERA of 4.07.

In 1952 Kress was hired by the Indians to manage the Daytona Beach Islanders in the Florida State League. He took on the job with his usual zeal. Sportswriters wrote that he tossed 90 minutes of batting practice the first day of training camp. The team started slowly at 10-14, but finished the first half of the season above .500, and when two franchises folded the team picked up players to help in the second half. A 77-59 record earned the Islanders a spot in the playoffs. They swept first-place DeLand in round one, but fell to Palatka in the finals. That December Kress was hired as an Indians coach. Tony Cuccinello handled third base and Kress was the first-base coach in a partnership that lasted until 1957. Red tossed lots of batting practice and worked with Ray Boone at shortstop. Cleveland won 92 games in 1953, but finished 8½ games behind the Yankees. That winter Kress managed the Gavilanes team in Venezuela to a third-place finish.

The Indians went to spring training in 1954 with a strong veteran cast. When the wins began to pile up and the pennant was assured, Cuccinello was sent to scout the Giants, and Kress shifted to the third base box for a short time. After pocketing his $3,356.25 losers’ share of the World Series money, Kress hired on the manage Santa Marta in the Venezuelan League. With a squad made of mostly of native players from Class C and D leagues, the team got off to a bad start, and Kress was fired in early November when its record was 4-9.

The 1955 Indians started to show their age, and finished in second place, three games behind the Yankees. That winter Kress went to Venezuela again to manage Gavilanes. He had a strong group of Indians farmhands, plus Luis Aparicio at shortstop. The team got off to a 7-0 start and fought for the pennant. On January 17 first-place Gavilanes was facing second-place Pastora in Maracaibo. Kress was coaching at third base and reports were that he was riding the Pastora players to the point of being insulting. In the sixth inning, Pastora manager Jim Atkins rushed from the dugout and socked Red in the nose, breaking broke it. A bench-clearing brawl ensued and it took police 15 minutes to get peace restored. Eventually the umpires declared a forfeit and gave the win to Gavilanes. The rest of the pennant race was spirited, but Gavilanes wrapped it up with one game to go. The players had been promised and extra two weeks’ salary if they won the pennant, but the ownership announced that it could not pay the bonus. Kress and the American players on the team sat out the last game of the season; he said in an article in The Sporting News on March 21, 1956, that the owners had benched the players and he sat out the game too in support of them.

In 1956 Kress was back as a coach with the Indians, who again finished second to the Yankees. That November the Estrellas Orientales squad in the Dominican League, which was stocked with Cleveland farmhands including Roger Maris, got off to a bad start and Kress was named manager on November 17. But he was fired a month later after little success.

Manager Al Lopez left Cleveland for the White Sox in 1957. Eddie Stanky replaced Cuccinello as a coach but Kress stayed on. He started collecting his pension that year, getting $265 a month. The Indians finished a distant sixth and manager Kerby Farrell was fired. Bobby Bragan was brought in to manage in 1958 and he retained the coaches. The Indians were rebuilding and the lineup was in constant flux. Not surprisingly the team struggled and Bragan was fired on June 26 with a 31-36 record. That fall Kress returned to Venezuela to manage Gavilanes, which finished 26-26. The 1959 Indians were a marked improvement over the ’58 version, but fell five games short of Al Lopez’s White Sox.

Kress was fired after the tumultuous 1960 season (slugger Rocky Colavito went to Detroit in a controversial trade for Harvey Kuenn, He did not stay unemployed very long. He was hired to help guide the expansion 1961 Los Angeles Angels. Angels manager Bill Rigney called him “one of baseball’s top coaches,” but Kress was fired at the end of the season. The brand-new New York Mets hired him to help in spring training and then manage in the minors, probably at Syracuse. But Mets manager Casey Stengel kept Kress as a coach. No amount of coaching from Kress or anyone else helped the first-year Mets, who finished 40-120. In October Kress returned to his home in the Canoga Park section of Los Angeles. He died of a massive heart attack on November 29. He was 55 years old. He is buried in Forest Lawn cemetery in Glendale, California.

This biography is included in the book Pitching to the Pennant: The 1954 Cleveland Indians (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Joseph Wancho. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Sources

Thanks to SABR member Bill Staples for articles about Kress in California winter ball

Kress’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame

Baseball.Reference.com

Sporting News, Reach, and Who’s Who guides and Cleveland Indians yearbooks

Newspapers from Oakland, St. Louis, Chicago, Los Angeles, Cleveland, Detroit, Minneapolis, Lakeland (Florida), Tucson, and Long Beach, and The Sporting News

Macmillan Baseball Encyclopedia and Total Baseball, various editions

David S. Neft, Richard M. Cohen, Michael L. Neft, Sports Encyclopedia: Baseball (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2000)

Full Name

Ralph Kress

Born

January 2, 1905 at Columbia, CA (USA)

Died

November 29, 1962 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.