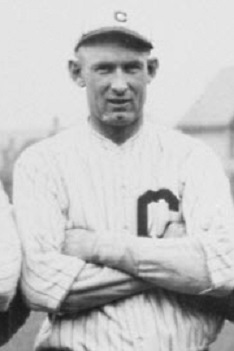

Rip Hagerman

Serious major-league fans know that Jack Chesbro was the last 40-game winner, posting 41 victories in 1904. Others are aware that Carl Hubbell won 24 consecutive games from July 1936 into 1937. These are major-league records, but at the lower levels of baseball, Rip Hagerman posted 46 wins in his first year of professional ball and created headlines with a 27-game consecutive win streak in 1919-1920.

Serious major-league fans know that Jack Chesbro was the last 40-game winner, posting 41 victories in 1904. Others are aware that Carl Hubbell won 24 consecutive games from July 1936 into 1937. These are major-league records, but at the lower levels of baseball, Rip Hagerman posted 46 wins in his first year of professional ball and created headlines with a 27-game consecutive win streak in 1919-1920.

Charles E. Hagerman was a Kansas farmer of German descent. He married Ella C. Archer and together they raised six children. Their second child, named Zerah Zequiel, was born on June 20, 1886, in Lyndon, Kansas. He grew to be a strong, healthy farmboy reaching 6-feet-2 and weighing around 195 pounds.1 Z.Z. attended school through the eighth grade before joining the labor force. He also developed into a talented baseball pitcher, although details of his early career are lacking.

In 1907, the Socorro, New Mexico, amateur team brought Hagerman in to anchor their pitching. The local paper raved, “[H]e has had plenty of experience and will not fail to deliver the goods.”2 No mention was made where this experience was gained and at what level. He quickly became the ace of the staff and showed excellent speed and “a double action, corkscrew curve ball.”3 The Socorro team became a powerhouse, winning tournaments and piling up wins. Late in the season the team was invited to a tournament in Albuquerque with teams from El Paso and other cities. Socorro loaded up with ex-major leaguers and Hagerman saw little action. The team finished second and won a $500 purse. After the season Hagerman returned to Kansas and took a sales job in Topeka.

Manager Dick “Duff” Cooley of Topeka in the Class C Western Association got word of Hagerman’s talent and signed him to play in 1908. Cooley opened the season with a five-man pitching staff; by season’s end only Hagerman remained of that original group. After exhibitions against local teams, the Kansas City Blues and the Chicago White Sox, the Topeka White Sox opened the season on May 3 against Webb City with Hagerman on the hill. He dropped his first game, 1-0.

Topeka battled Wichita and Oklahoma City until a late 13-game winning streak put the team permanently in first place. Hagerman made five starts and four relief appearances during the streak. Regarded as having the best speed in the league, he wound up with 56 appearances and a 30-17 record for the champions. He hurled three one-hitters and had 11 shutouts.

Hagerman was recruited to play for a Key West team against teams from Cuba in November. He posted a 2-1 mark in the series. His performance earned a trip to Havana, Cuba, where he joined the Habana team and future Hall of Famers Pete Hill and John Henry Lloyd for the 1908-09 season. Hagerman was by far the best American pitcher in the league and challenged island legend and future Hall of Famer Jose Mendez for league dominance. They both won 14 games, but Hagerman dropped only five to Mendez’s seven.4 Mendez had the better ERA and WHIP. Habana claimed the title over Mendez’s Almendares team.

Hagerman had a reputation as a lady’s man. He was tall, blond, and athletically built. His handsomeness was responsible for his Cuban nickname of “Chelito.” The name had nothing to with Hagerman’s looks; he was tagged with it because of a female admirer. A Havana dancer, possibly a ballerina, named Chilito “was madly in love with the pitcher and occupied a box in the grandstand every time Hagerman pitched.”5

Hagerman’s first year of professional baseball lasted from April 1908 to March 1909. He won at least 46 games while playing against and with some of the game’s best. Topeka sold his rights to the Chicago Cubs for $3,000 and he became the first American to reach the majors after his initial Cuban season.

The Cubs tried to lowball Hagerman in salary negotiations and it nearly backfired on them. He had earned a very nice salary in Cuba. (Estimates were as high as $400 a month.) This was well beyond what Topeka had paid. The Cubs offered a figure below his Topeka salary and Hagerman suggested he might stay on the island for the next season.

Hagerman held the cards in this case. A National Agreement clause stipulated that a player moving to the majors could not be paid less than he had in the minors. Cooley, who had joined Des Moines in the Class A Western League offered to buy Hagerman for his new franchise. The Cubs came to their senses and a contract was worked out.

Hagerman had come a long way. When he began with Topeka he was “as green as a gourd.”6 Now he was joining the reigning world champions and their pitching staff anchored by Mordecai Brown, Ed Reulbach, and Orvie Overall. He had the arm and the stuff to make it, but he was slow afoot. A Topeka writer had observed that Hagerman “runs nearly as fast as a cow can walk.”7 His lack of agility as a defender “would make him a joke in the big leagues,”8 feared one writer.

The big-league scribes took a liking to the youngster and used all the descriptives at hand to describe him. He was lanky, a giant, a fireballer, lady’s man, and the Cuban Wonder. They also had fun with his name and nickname. The obvious were ZZ and Zee Zee. A fun combo was Rip Zip. They poked fun at his agrarian roots and called him the Mayor of Hayfield, Minnesota. Proving they knew about his Cuban admirer some dubbed him the Cuban Dance Master.

Hagerman made his major-league debut on April 16 when he was given the start against Slim Sallee and the St. Louis Cardinals. Hagerman pitched well except in the fourth inning, when he issued two walks and allowed three hits, leading to three runs. He was pulled in the eighth in the 3-1 loss.

On May 7, Hagerman tossed the first shutout of the season for the Cubs, topping Cincinnati 5-0. The Cubs would throw 31 more shutouts during the season on their way to 104 wins. Despite those gaudy numbers, they finished behind Pittsburgh and did not hold first place after May 29. Hagerman made seven starts in his 13 appearances and posted a 4-4 record. He handled 23 fielding chances without error, but was still considered a below-average defender. At bat, he struck out in half his plate appearances and hit .130.

Over the winter Hagerman’s name came up in trade rumors involving Cincinnati. At one point he was going to be part of a trade for Hans Lobert, then he was offered even-up for pitcher Bob Spade. No swap ever materialized and Hagerman signed his contract quickly for 1910. In spring training he did not show the speed or control he had the previous season. On April 19 he was sold to the Louisville Colonels in the American Association. He got his first start with the Colonels on April 23 in the snow against Indianapolis. He lost 3-2. He followed this with a victory over Columbus, but after a relief appearance he was sold to Lincoln in the Western League on May 14.

The Railsplitters never made a strong challenge for the pennant and finished in third place. Hagerman made 26 appearances and posted a 14-9 mark. At the plate, he batted a measly.101. The highlight of 1910 for him was his marriage to Margaret Maude McQuade on May 18. The couple would have one child, Catherine.

Little was changed in the Railsplitters lineup for 1911 and they finished in sixth place. Hagerman became the workhorse and went 17-15. He struggled with his control, walking more than three men a game on average. His lowly batting average dropped even lower, to .091.

The Lincoln roster was greatly changed for 1912. Young Nebraska hurler Harry Smith was available for the entire season and he won 19 games to go with Hagerman’s 23 victories. The pair worked 631 innings, but Lincoln still could not contend and closed the year 83-81.

Over the winter, manager Walt “The Judge” McCredie of Portland in the Pacific Coast League purchased Hagerman for $2,500. The Beavers assembled a powerful squad anchored by a pitching staff that included Harry Krause, Bill James, Gene Krapp, Irv Higginbotham, and Hagerman. The quintet each pitched over 200 innings and only Krapp (12-13) turned in a below-.500 record. Portland closed out the season with 109 wins and the league title.

Hagerman came to Portland with the reputation as “the right sort of man. He is modest, intelligent, and has good habits. He is not one of the carousing sort and is a credit to his team.”9 That description masked Hagerman’s inner wildchild. He was a man-ahead-of-his-time, a “motorcycle speed merchant.”10 He had a borrowed motorcycle and rode it around the training camp. His “high-priced, four-cylinder” auto had not been shipped from Lincoln yet. His intention was to enter it in races later that summer.11 In 1916 his love of the internal-combustion engine led to tragedy. He was driving in Santa Ana, California, when a 12-year old girl dashed into the street chasing a ball. She got into Hagerman’s path and the collision was unavoidable. The girl was killed and the next day a coroner’s jury cleared Hagerman of any wrongdoing.

The Portland franchise had a working agreement with the Cleveland Naps which McCredie characterized as “a personal matter between Charley Somers and myself.”12 In mid-January of 1914, the Naps acquired Hagerman from McCredie. The sale to Cleveland came about a week after Hagerman had visited the Federal League offices in Chicago. Whether he signed with the Feds is a matter of conjecture. In the end, Hagerman signed with the Naps but reported late to New Orleans, causing minor concern for manager Joe Birmingham. Once in camp, Hagerman impressed with his pitching, but still needed work on his fielding.

The 1913 Naps had finished in third place. They lost right-handed ace Cy Falkenberg to the Federal League, but hoped that some youngsters from 1913 and Hagerman would fill the void. One of those returnees was Nick Cullop, who fled to the Feds shortly after the season began. The Naps opened 1914 with eight consecutive losses, the first seven on the road. On April 23, the Naps beat the White Sox 4-1 for their first win. Hagerman made his third start the next game and tossed a four-hit shutout at the White Sox, winning 1-0.

Despite the two-game winning streak, the Naps were firmly positioned in last place and would never escape the cellar. Lefty ace Vean Gregg nursed his sore arm to nine wins by late July when he was swapped to the Boston Red Sox. Lajoie’s star had blown out and he hit .258. Joe Jackson saw his average slide 35 points to .338. The Naps finished with 51 wins; Hagerman had nine of them. He added shutout wins on May 10 over St. Louis and July 16 against the Senators.

Hagerman made 26 starts in 37 appearances. He was third on the team in innings pitched and second in ERA. His control was more of an issue than his fielding as he walked 118 batters. The Naps were in dire shape and welcomed him back for 1915 as one of their mainstays. Guy Morton, Willie Mitchell, and Hagerman led the staff in 1915 to 57 wins and a seventh-place finish.

Hagerman’s 1915 season proved tougher than 1914. The low point came on July 19 when Cleveland hosted Washington. Hagerman was matched against Walter Johnson, but did not last through the first inning. His mind must have been on something other than the game. He walked three of the first four hitters and committed a balk. More egregiously, he seemed to lose all concept of holding runners. Leadoff batter Danny Moeller walked and then stole his way home. Clyde Milan had walked and stolen his way to third before scoring on a triple. That ended Hagerman’s day. He was replaced by Sam Jones, who proceeded to put runners on base and they added three more steals. The net effect of all this larceny was that catcher Steve O’Neill, regarded as one of the better defensive catchers in baseball, had surrendered eight stolen bases in an inning.13 Up 6-0 after the first half-inning, the Senators recorded no more steals in the 11-4 win.

The best pitching performance of Hagerman’s 1915 season came eight days later in a loss to Washington and Bert Gallia. Clyde Milan scored a first-inning run on a steal of home, but that was the only score of the game. Hagerman twirled a two-hitter and Gallia allowed only one hit. Hagerman closed out 1915 with a 6-14 record.

Hagerman went north with the team in 1916, but gave up six runs in his two appearances. On May 10, the Indians asked waivers on him. He was sent to Portland on May 23. His return to the Coast did not go smoothly. Ragged performances and a sore arm limited his role. Hagerman was a competitor and it was hard to hold him down. On June 3, he walked seven in the first two innings versus Los Angeles and was sent to the showers. He rebounded the next day to beat Los Angeles 4-1. After the sore arm in late June, he was mainly a reliever. In that role on September 23 against Oakland, Hagerman closed out both games after the Beavers had taken a one-run lead in the top half of the final inning. Nowadays he would have gotten two saves. On January 22, 1917, he was swapped to St. Paul for catcher Bob Marshall.

The St. Paul Saints in the American Association were guided by Mike Kelley and held spring training in Beaumont, Texas. Hagerman was used in both relief and a starting role in spring training and then during the season. The team got off to a poor start, standing 3-9 on April 30. The Saints finished 88-66, tied with Louisville in second place behind Indianapolis. Hagerman posted a 14-10 record, but his 126 walks pushed his WHIP to a team worst 1.397.

Kelley had soured on Hagerman and did not tender him a contract until spring training was nearing an end in 1918. Used predominantly in relief, he posted an 0-5 record. His highlight came July 6 when he struck out 10 in a relief role. A week later he was notified by his draft board to find gainful employment or face a Classification of 1 (equivalent to World War II’s 1A). Soon after, the American Association disbanded and Hagerman found defense-plant employment in Duluth, Minnesota.

Dozens of baseball players flocked to Duluth to work in the shipyards and steel mills. Many companies fielded teams, Hagerman pitched for Open Hearth in the Steel Plant League. He also toed the rubber for Globe Shipyards. The Globe team became part of the Twin Ports-Mesaba League, which organized in late August of 1917. Globe represented Superior, Wisconsin. The other entrants were from Hibbing, Minnesota, Duluth, and Riverside, Minnesota.

In 1919, Hagerman worked for Nash Motors in Kenosha, Wisconsin, before moving the family to Alma, Michigan. There he worked in the Republic Truck factory and played for the Republic Truck semipro/industrial team. He won every game he pitched for the Republics in 1919 and continued the streak into 1920 before he was finally defeated by the Toledo Railsplitters after 27 consecutive wins. The Alma team claimed a 42-10 mark at season’s end. They proclaimed themselves Midwest semipro champions by having beaten those teams regarded as their best competition. They based their claim on “never losing a series” even though they split series with four teams.14

Hagerman spent the next couple of years as a baseball nomad. He played for the Briscoes of Jackson, Michigan, then joined the Buick team from Flint, Michigan. He made a stop in Sturgis, Michigan, playing for the local team before settling down in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

Hagerman joined the Kenosha Nash team, which played in the semipro Midwest League. It included two Chicago teams, two Ohio teams, and four squads in Wisconsin. His debut with Nash was a 2-0 shutout of the Massillon, Ohio, entry. The league unraveled in the middle of September with Beloit in first place. The following year the Nash team combined with another squad to form the Kenosha Twin Sixes and played in the semipro Wisconsin State league. The Twin Sixes cruised away from the competition and won the pennant. Suffering from tuberculosis, Hagerman moved with his family to New Mexico after the 1925 season.15

Hagerman’s fascination with automobiles had led to a series of jobs in truck and auto factories. In Albuquerque, he found a sales job at the Don Wilson Garage. There he sold Dodges and Hupmobiles. His health deteriorated and he died at home on January 30, 1930. He is buried in Mount Calvary Cemetery in Albuquerque. Margaret and Catherine continued to live in Albuquerque for many years.

Baseball Reference lists Rip Hagerman with the Oklahoma City Indians in the Western League in 1924-25. Described as young and fast, the Oklahoma player had the same nickname, but was not the same person. The Oklahoma “Rip” appears to be Howard F. Hagerman. He pitched for Edmonton in 1922 in the Western International League. He played semipro ball in Minot before becoming a pitcher-outfielder with the Cushing Refiners in the Oklahoma State League in 1924. When that franchise folded, Howard Hagerman was signed by the Indians. He pitched a few games in 1924, fostering the confusion, before becoming an outfielder exclusively. He appeared on the Indians’ voluntarily retired list after the 1925 season.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by Alan Cohen. Thank you to SABR member W. David Green of Oklahoma who researched the Daily Oklahomian to help identify the 1924-25 player. Cassidy Lent at the Giamatti Library in Cooperstown also provided a crucial clue.

Notes

1 Baseball Reference lists Hagerman at 200 pounds. Newspapers over his career range from 180 to 195.

2 “Notes on Baseball,” Socorro (New Mexico) Chieftain, June 29, 1907: 1.

3 ‘Baseball at Socorro,” Socorro Chieftain, July 20, 1907: 4.

4 Cuban historian Jorge S. Figuereido listed both men at 15-6 in Cuban Baseball, A Statistical History, 1878-1961. That record is also used by Peter Bjarkman in his A History of Cuban Baseball. The stats listed are from Baseball-Reference.

5 “New Hurler Liked,” The Oregonian (Portland), January 4, 1913: 14.

6 ‘They’re After ‘Rip’ Hagerman,” Kansas City Star, December 23, 1909: 16.

7 “Made the Oklahomans ‘Eat Dirt,’” Topeka Daily Capital, June 18, 1908: 2.

8 Topeka Daily Capital, August 15, 1908: 2.

9 “New Hurler Liked,” The Oregonian, January 4, 1913: 14.

10 “‘Rip’ Motorcycle Enthusiast,” The Oregonian, March 16, 1913: 4.

11 Ibid.

12 Roscoe Fawcett, “Beaver Pact With Cleveland Broken,” The Oregonian, February 17, 1916: 14.

13 “Stole Eight Bases in a Single Inning,” Washington Evening Star, July 14, 1918: 49.

14 “Semi Pro Champs of Middle West,” Saginaw (Michigan) News, October 17, 1920: 24.

15 “Deaths and Funerals,” Albuquerque Journal, January 31, 1930: 9.

Full Name

Zerah Zequiel Hagerman

Born

June 20, 1886 at Lyndon, KS (USA)

Died

January 30, 1930 at Albuquerque, NM (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.