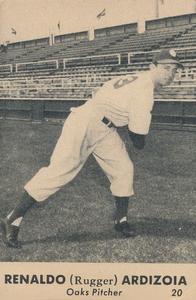

Rugger Ardizoia

The steamship S.S. Colombo arrived in New York from Naples, Italy, on December 6, 1921, bearing a boy who had just turned two years old, Rinaldo Ardizzoia, accompanied by his mother, Annunziata (Mossina) Ardizzoia, a tailor from Oleggio, in northern Italy, where Rinaldo had been born on November 20, 1919. The mother and son were on their way to Port Costa, California to join husband and father Carlo Ardizzoia, who had sailed to the United States thirteen months earlier.[fn]Rugger Ardizoia interview, February 6, 2010. Asked about his mother being recorded in the census as a tailor, he said, “She was very, very good. She worked at a place where they made clothes and repaired them.”[/fn]

The steamship S.S. Colombo arrived in New York from Naples, Italy, on December 6, 1921, bearing a boy who had just turned two years old, Rinaldo Ardizzoia, accompanied by his mother, Annunziata (Mossina) Ardizzoia, a tailor from Oleggio, in northern Italy, where Rinaldo had been born on November 20, 1919. The mother and son were on their way to Port Costa, California to join husband and father Carlo Ardizzoia, who had sailed to the United States thirteen months earlier.[fn]Rugger Ardizoia interview, February 6, 2010. Asked about his mother being recorded in the census as a tailor, he said, “She was very, very good. She worked at a place where they made clothes and repaired them.”[/fn]

Twenty-six years later, that same boy pitched in the Major Leagues for the New York Yankees. In a February 2010 interview, he was asked what brought his father to the United States, and he replied, “The man who owned the brickyard in Port Costa, he was from my home town and he invited a bunch of Italians over to come to America and have a job.”[fn]Los Angeles Times, June 3, 1939.[/fn]

In 1923 the family moved to San Francisco. Rinaldo had lost his mother two months after his sixth birthday to what he understands was double pneumonia. While living in San Francisco as a youngster, Rinaldo added the middle name Joseph—not Giuseppe; Joseph was a confirmation name. He thought he picked up his nickname around this time. “I was all by myself. My father was working and I was only six years old. I lived across the street from a playground and I used to go over there and play marbles and fool around and get in fights. Guys would chase me. We had a bunch of thistle back there that wasn’t cleared and I’d run into the thistle and they wouldn’t chase me. They’d say, ‘You’re a rugged little bugger.’ I also played rugby and I was a Rugger there.”[fn]Interview by Ed Attanasio on November 21, 2006. All quotations from Ardizoia are from this 2006 oral history unless otherwise noted.[/fn]

In 1931, the Catholic Youth Organization began a baseball team and Ardizoia played for St. Theresa’s Church CYO. Next came play in American Legion ball and at the High School of Commerce. He had favored football as a youngster, and was a third baseman when he first started playing baseball. It was only in his junior year at Commerce that he took up pitching. He threw two no-hitters in high school, and in one of them opposing pitcher Art Gigli also threw a no-hitter. The game had to be called off because it ran too long, neither team ever getting a base hit.

The day he graduated from high school in 1937, the seventeen-year-old signed a contract with the Mission Reds of the Pacific Coast League (the team represented San Francisco’s Mission district). Actually, he had signed while he was still in high school, six months before his graduation. Offered a scholarship to Stanford University, he had to turn it down because he had already turned professional.[fn]Los Angeles Times, June 3, 1939.[/fn]

Ardizoia’s father was working as a warehouseman in 1937, earning $25 a week. His son now was making $150 a month. “That’s when he quit,” Rugger said of his father. “He said, like an old Italian, ‘I supported you for seventeen years, now you support me, OK?’ … Money was pretty good and so when I turned twenty-one, I bought this house. … I’ve been in this house here sixty-five years.” On January 11, 1942, Ardizoia married a fellow Commerce student, Mary Castagnola, a twenty-one-year-old native of San Diego.

Ardizoia threw 24 2/3 innings in nine games with Mission, and had a remarkable first game. “We were in San Diego and they had [Jimmy] Reese and Ted Williams and a whole bunch of those old guys and Johnny Babich started and I relieved in the second inning and I pitched the next five innings of one-hit ball. That was my first game in professional ball. After that, look out!”

He fondly recalled those early days: “I had all these old guys around me and I was just a young guy and they all teased me and all that. We got along real good, though. That’s one thing about the old days. There was [sic] no individuals. They were a team. … In those days, you pitched. You didn’t count pitches. You didn’t count innings. You just got it on. You got the guy out. I went as high as eighteen innings complete.”

More than anyone else, some of the catchers he worked with taught the five-foot-eleven, 180-pound right-hander how to pitch. “I had a fastball. I had an overhand curve, a three-quarter curve, and a sidearmed curve—three different types—and some little sinker ball. Then later on when I started with Oakland I picked up a slider.”

Ardizoia posted a 5.84 ERA in 1937 but didn’t record a decision. It was in 1938, pitching for the Bellingham (Washington) Chinooks in the Western International League, that he first got in a full season of work, 224 innings, with a 12-13 record and a 3.05 earned-run average. During the offseason, he pitched in the San Francisco Winter League. He credited manager Ken Penner of Bellingham with teaching him how to hide his pitches better.

In 1939 and 1940 Ardizoia pitched for the Hollywood Stars of the PCL. He first became associated with the New York Yankees in December 1939. The New York World-Telegram reported that Yankees had acquired Ardizoia in exchange for pitchers Hiram Bithorn and Ivy Andrews. Ardizoia, described as the best pitching prospect in the Pacific Coast League, had finished the season 14-9 with a 3.98 ERA.

It was intended from the start that Rugger would spend 1940 with Hollywood. He won 14 and lost 20 that year, and his 145 strikeouts were fifth highest in the league. In August 1940 the Yankees officially purchased his contract and in the spring of 1941 he trained with the Major League club.

After spring training, the Yankees sent him to the Newark Bears of the International League, but early in the season a problem cropped up. The International League included two clubs from Canada, Montreal and Toronto. Ardizoia was 0-1 with Newark before the Bears general manager realized Ardizoia was not a U. S. citizen. A trip to Ellis Island affirmed that he was legal in the United States, but Canada wouldn’t let him into the country. They were at war with Italy, and that made Rugger an enemy alien. “So I got sent to Kansas City. In those days, you had to wait two years and go before a judge and all that stuff. In the meantime, I got trapped in World War II and even though I wasn’t a citizen, I accepted the induction (into the U.S. Army),” he said. Before being drafted, however, he got into twenty-seven games for the Kansas City Blues of the American Association, going 12-9. Back with the Blues in 1942, he won six and lost twelve.

Rugger served in the army air force from May 1943 until he was discharged in November 1945. After eight months at McClellan Field, near Sacramento, he was transferred to Honolulu on June 1, 1944. Rugger joined the 7th Air Force’s baseball team there, compiling, he recalled, a 12-0 record. In Hawaii he became a tow target operator, flying over a firing range towing a target with a cable that was from 250 to 2,500 feet long. Baseball may have saved him his life, he remembered with a bit of understatement: “One night that I was supposed to fly, I was relieved because we had a ballgame. The plane crashed. I was lucky.”

Ardizoia joined a team that took him to some of the islands in the Pacific—Tinian, Saipan, and Iwo Jima. Playing baseball on volcanic and coral islands that had recently seen vicious fighting wasn’t always the easiest of duty. There were still worries that a Japanese soldier would emerge from concealment and open fire. “There were so many zigzags there [in the tunnels], they didn’t know if they got them all. They were hiding in the hills. We’d play every day or two. In the meantime, we had KP and cleanup jobs and stuff like that,” Ardizoia recalled.[fn]Rugger Ardizoia interview, December 10, 2008.[/fn]

When Corporal Ardizoia was discharged from the service at Camp Peale, California, he spoke up and said, “Hey, I want to become a citizen.” The officer was a little stunned. “Aren’t you a citizen? What the heck are you doing in the Army?” “I volunteered because this is my country.” He was told, “OK, stick around for a couple of days.”

“I said, ‘No way.’ My son was eighteen months old and I hadn’t seen my wife for three years. So I came home and then went down to the Federal Building and went before the judge. He had me raise my right hand and he says, ‘Do you solemnly (swear) to defend the United States . . . wait a minute, you just came out of the Army?’ I said, ‘Yessir.’ He says, ‘You‘re a citizen.’”[fn]Ibid.[/fn]

In 1946 it was back to baseball, this time with the Oakland Oaks in the PCL. Rugger had an excellent year on an Oaks team that won 111 games for manager Casey Stengel. Rugger was 15-7 with a 2.83 ERA. The three seasons he lost during the war hadn’t hindered him. His only home run in pro ball came in 1947, against Seattle.

In 1947, Ardizoia went to spring training with the Yankees again. He stuck with the big-league team for a while and finally had his opportunity to play in a Major League game. It was the last day of April. The Yanks had just arrived in St. Louis for a game against the Browns. When Ardizoia was brought on to pitch the bottom of the seventh, St. Louis had a 13–4 lead. He got through the seventh, but former Iwo Jima teammate Walt Judnich hit a homer in the eighth, one of two runs Rugger gave up.

As Ardizoia said in the 2006 interview, “The guy that hit the home run off me was one of my boyhood idols, Walter Judnich. I more or less slid it in for him because we were so far behind anyway.” Johnny Lindell pinch-hit for Rugger in the ninth. It was Ardizoia’s only Major League appearance, but by doing so, he became one of only seven natives of Italy to play in the Major Leagues.

After another week of throwing batting practice, Rugger was sold to Hollywood on May 8 and played the rest of the season for the Stars, going 11-10. His time in the majors was over; the Yankees won the World Series that year but Ardizoia never received either a ring or a World Series share.

In 1948 Rugger was with Hollywood again. In January 1949 he was traded to the Seattle Rainiers. He began the 1950 season with the Rainiers, but got into only two games, spending most of the year with the Dallas Stars in the Texas League, where he went 10-10. He pitched a second season for Dallas in 1951, and was 8-3 with a 2.88 earned run average.

After that season he retired from the game. He said he had a bone chip in his throwing arm and wanted to spend more time with his two children in San Francisco. Ardizoia finished baseball with just that one brief Major League appearance, with the 1947 Yankees. In the minors, he pitched for twelve seasons and won 123 games against 115 defeats, with a 3.63 ERA.

Ardizoia had worked during the off-seasons for Owl Drug Company, a retail chain. Owl had a baseball team and he played winter ball for it in the Bay area, but also put in eight-hour days. He worked for Owl until it went out of business, and then took up work as a salesman for Galland Linen and then National Linen Service. He worked at selling rental linen for about thirty years. Baseball helped. “A lot of accounts, people knew that I played ball and in those days they still remembered.”

Rugger’s wife, Mary, died in April 1983. The couple had two children, both born in San Francisco: Bill, in June 1944, and Janet, in April 1947. Janet died in April 2010.

The Yankees kept in touch, sending Ardizoia their alumni mailings, Christmas and birthday cards, and a big bouquet of flowers on his 85th birthday. After the 2009 World Series win, they sent him a medallion celebrating their 27th world championship. In 2009 a journalist in Italy wrote a story about him. Ardizoia helped start and remained a member of the San Francisco Old Timer’s Baseball Association, a group mostly of semipro players, but open to anyone who played baseball.

Ardizoia remained active until the end of his life, working for a number of years with the Pacifica Beach Coalition and participating in their April 2015 Earth Day of Action and EcoFest event. In June, he attended a Giants game and presented a check for $1,000 to a graduating high school baseball player. He suffered a stroke on July 11 and died of complications eight days later, on the 19th, at his home in San Francisco.

This biography is included in the book “Bridging Two Dynasties: The 1947 New York Yankees” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by Lyle Spatz. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Sources

Oral history done by Ed Attanasio on November 21, 2006 was transcribed by Tom Hetrick in February 2007.

Interviews by Bill Nowlin on December 10, 2008 and February 6, 2010. Correspondence from Rugger Ardizoia on February 17, 2010.

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed the online SABR Encyclopedia, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Full Name

Rinaldo Joseph Ardizoia

Born

November 20, 1919 at Oleggio, Novara (Italy)

Died

July 19, 2015 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.