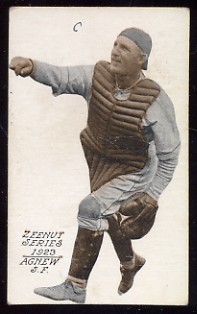

Sam Agnew

Sam Agnew is best remembered for being the catcher for both of Babe Ruth’s pitching victories in the 1918 World Series. Although Agnew did not get a hit in the four Series games in which he played that season, he caught Ruth’s complete game shutout in Game One and eight innings of Ruth’s pitching in the tightly-contested Game Four before being removed for pinch-hitter Wally Schang in the bottom of the eighth; Schang singled and scored the game-winning run. A Hartford Courant subhead in mid-September, when a number of players appeared in an exhibition game in Connecticut’s capital, read, “Ruth and Agnew Regarded as One of Strongest Batteries in Majors.”

Agnew shared the catching duties with Schang and Wally Meyer in 1918, catching the most games of the trio. He was known for taking risks trying to throw out baserunners, which contributed to his leading the league in errors twice in three years while with the St. Louis Browns, with 28 errors in 1913; 25 in 1914; and 39 in 1915. In 1918, however, Agnew made only 13 errors, one of the lowest totals of his career, albeit in fewer games.

As a major leaguer, Agnew was never known for his hitting. Playing in 72 games in 1918, the right-handed batting Agnew got only 33 hits in 199 at-bats, finishing the year with a .166 average, no home runs, and six runs batted in. In fact, Agnew never hit better than .235 or drove in more than 24 runs in any of his seven major league seasons.

Samuel Lester Agnew’s first professional baseball experience came in California with Vernon of the Pacific Coast League in 1912. There, the Farmington, Missouri, native had a strong offensive season, hitting .283 with five home runs. His performance caught the eye of the St. Louis Browns, who selected Agnew in the day’s equivalent of the Rule 5 draft. One thing that had caught their eye: He was reported to be the only catcher in the United States who had caught more than 100 games without a passed ball.

Agnew made his major league debut with the Browns two days before his 25th birthday, on Opening Day, April 10, 1913, in a 3-1 St. Louis victory over Detroit. Agnew’s rookie season was his best offensively: The 5-foot-11, 185-pound backstop had a career-high nine doubles and five triples and stole 11 bases. Agnew also hit the only two home runs of his career in 1913, the first a three-run homer off Boardwalk Brown on June 11 and the second a solo homer served up by Russ Ford on July 13 at Sportsman’s Park.

Agnew’s rookie success was short-lived. On July 25, 1913, in a game against the Washington Senators, Agnew suffered a broken jaw after being hit by a Joe Engel fastball. During that game, which ended in an 8-8 tie after 15 innings, Johnson struck out 15 batters in the last 11 innings. Agnew was hospitalized for a week, until August 1; he began work again with the Browns on August 20. He completed the year hitting .208 with the two homers and 24 RBIs. After the regular season was over, Agnew took part in a spirited city championship series in which the Browns beat the Cardinals, the final doubleheader apparently degenerating, as reported in the New York Times to a “fist fight between players, numerous verbal battles between the managers, the desertion of the umpires, and many other existing features.”

Agnew caught more than 100 games in both 1914 and 1915 for the Browns, but the team languished, finishing in seventh place in both seasons. In 1914, he caught 115 games and hit .212, driving in only 16 runs. The following year, he hit .203 in 104 games with 19 RBIs. Incidentally, he led the league in passed balls both years, with 18 and 17 respectively. Once more, the Browns won the St. Louis city series. Agnew made one headline after a bizarre moment on August 18, 1914, when he was called out by the umpire while sitting in the Browns dugout. With two runners on base, when Tilly Walker came up to bat in place of Doc Lavan, umpire Evans noticed that, according to the lineup card, the Browns had been batting out of order. Agnew was supposed to be batting, not Lavan. Agnew was called out and Wallace, who had singled, was removed from first base.

On December 16, 1915, Agnew was sold to the Boston Red Sox, who wanted him to serve as a backup to incumbent catcher Pinch Thomas. He had impressed with his ability to cut down basestealers; in 1915, Agnew had thrown out Harry Hooper six times. Despite his anemic batting average, the Boston Globe termed the new acquisition “a fine all-around player” and asserted that “he is a pretty good batter.” The price was apparently $10,000. League president Ban Johnson announced that the deal would not be allowed to go through, but he was soon forced to back down

Although Agnew played in only 40 games in 1916 with Boston, he was involved in one of the most dramatic incidents of that season. During a June 30 game, Senators shortstop George McBride threw his bat at Boston pitcher Carl Mays, who had hit McBride with a pitch. In the ensuing brawl, Agnew reportedly punched Washington manager Clark Griffith in the face. The outcry was so great that Agnew was arrested on the field, and Boston manager Bill Carrigan was required to bail him out of jail. Fortunately for Agnew, all charges were ultimately dropped.

Agnew and Hick Cady both backed up Thomas throughout the 1916 season. Thomas, Cady, and Carrigan all saw service in the World Series, but Agnew did not. He was, however, the first player to report to Hot Springs for spring training in 1917.

Now 30 years of age, Agnew caught more games than any other Boston catcher in both 1917 and 1918. Appearing in 85 games to Thomas’s 83 in 1917, he hit .208 and drove in 16 runs. In 1918, after a brief holdout in spring training, Agnew appeared in 72 of the season’s 126 games, batting just.166.

Agnew did have his moments in the 1918 World Series: Though hitless in nine at-bats, he threw out three of the four Chicago Cubs baserunners who tried to steal against him and played errorless defense.

As noted above, Agnew and Babe Ruth were among those who played in a three-game exhibition series in Hartford; the final game on September 15 saw Ruth outpitch Dutch Leonard, 1-0, and Agnew single in the winning run in ninth inning of the rubber game.

In March 1919, Agnew was purchased by the Washington Senators. The move was surprising in that the Senators were still managed by Clark Griffith, with whom Agnew had brawled three years earlier. The Washington Post headline read: “Griff Will Have Real Scrapper. Claims Agnew, Red Sox Catcher, Who Punched Him in 1916.” As one contemporary article noted, “Griff is likely to have a little difficulty in getting [Agnew’s] signature to a contract. [Lest] we forget, a couple of years ago, Griff and Sam had a punching match at Fenway Park, which resulted in Sam being grabbed by a man who wears a blue coat and brass buttons.”

The six-year veteran was a known quantity at the time, but it was his work behind the plate — rather than at it –that presented value. The Post noted, “When it comes to slugging, as we know it in baseball, Sam is in the never-was class. Anything over a .200 batting average is as found money to him. But Sam can catch.” His defensive work had improved remarkably during his years in Boston.

With the Senators, Agnew played behind catcher Val Picinich. He caught only 36 games for the seventh-place Senators, appearing in six other games, and batting a career-high .235, with 10 RBIs. But he often served as the preferred catcher for Walter Johnson, because, according to the Post‘s J.V. Fitz Gerald, “he puts plenty of life and ginger in his work, something Johnson likes in a batterymate.”

Agnew’s major league career was over following the 1919 season. In addition to the eventual Hall of Famers who Agnew played with in Boston, Agnew in his career had also been a teammate of Walter Johnson, Branch Rickey, and George Sisler.

Agnew’s career actually got a boost after he left the major leagues. He was purchased by the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League for the 1920 season, where he became, according to his obituary in the August 1, 1951, issue of The Sporting News, “a favorite with the fans in the Bay Area” over what would become almost an eight-year stay with the team. There was a hitch at the start of the long relationship, though, when he balked at the pay he was offered. The Washington Post said he “shocked” the team with his salary demands. The Coast League played a longer season, and Agnew said he would need more than he was paid in the major leagues for that very reason, since he “must hire a man to run his farm for a longer period.”

In four of those seasons, Agnew batted over .300, and he hit more than 10 home runs in a season five times. Agnew was a key contributor to the 1925 Seals team that went 128-71, hitting 20 home runs, driving in 85 runs, and batting .326.

With the Seals, Agnew had the chance to catch Lefty O’Doul, Ernie Shore, and Walter Mails, among others. In the Coast League, Agnew also formed a strong friendship with Seals teammate Archie Yelle, a major leaguer with the Detroit Tigers from 1917 to 1919. Agnew’s obituary in The Sporting News recounted the following incident, as told by Agnew’s good friend, sportswriter Abe Kemp:

“One day, Agnew suspected that Yelle was injured in a close play at the plate. Archie brushed Sam aside when he offered to catch the remainder of the game. After the game Yelle dressed beside [Charley] Graham [the manager of the Seals]. As he took off his right shoe, blood splattered over the floor.

“‘When did you get cut, Arch?’ ” said Graham.

“‘In the second inning,’ ” replied Yelle.

“‘Why didn’t you mention the accident when it took place?’ “

“‘Sam has been working too hard,’ was Yelle’s laconic answer.”

Agnew was ambitious. In late 1922, while playing some winter ball with San Bernardino’s Santa Fe team, he partnered with two area men and organized the San Bernardino Baseball and Amusement Association, which planned to build a ballpark and launch a new Class B or Class C league in Southern California. In January 1923, backed by “unlimited financial interests” (Los Angeles Times), he shifted to trying to purchase the Salt Lake City Bees ballclub and move it to San Bernardino. The move never happened and Agnew kept on playing.

Agnew finished his playing career with Hollywood of the PCL, playing for the Stars at the end of the 1927 season and throughout 1928. At age 41, Agnew finished his playing career and opened a gas station in Boyes Springs, California.

Sam Agnew’s brother was Troy Agnew, who had an accomplished minor league career and was the player-manager for the 1924 Okmulgee Drillers team that had a 110-48 record in the National Association. Troy went on to run the Augusta franchise of the Sally League in the 1930s, and Sam managed. Troy later bought the Palatka Azaleas in the Florida State League.

Troy hired Sam to manage the Azaleas to start the 1937 season. However, according to a July 29, 1937, newspaper account, the Agnew brothers had several run-ins with the local community, “including a report that the city had refused water to [the team] to sprinkle the diamond and police to patrol the park. Now Mayor J.W. Campbell is rallying the citizens to the support of the club as a civic enterprise to show the Agnews the city is behind the team.” Sam Agnew soon left to become the manager of the team in Augusta, under his brother Troy.

In December 1939, Sam Agnew purchased the Meridian, Mississippi, team in the Southeastern League, where “he will be in complete charge next season,” according to one newspaper report. With experience managing minor league teams in San Diego, Augusta, and Palatka under his belt, Sam had taken the next step. The team had been known as the Scrappers since 1937, but fans argued for a name change to something more robust. Sam approved a contest run by the local Meridian Star newspaper to pick a new name, and the team became the Bears for the 1940 season. But the Mississippi team struggled to be economically viable from the start, and Sam publicly proposed relocating the team to Florida, making his tenure as owner a rocky one.

Agnew battled a severe heart condition in his later years. He slipped into what his obituary called a “semi-coma” for months before having a “miraculous” recovery in November 1950. His heart trouble caught up with him, however, and Sam Agnew died on July 19, 1951, at a hospital in Sonoma, California, at the age of 63. He was survived by his wife, Dorothy. Agnew is buried at Chapel of the Chimes Cemetery in Santa Rosa, California.

Sources

Agnew’s bio and World Series information on baseballreference.com, retrosheet.org, 1918redsox.com, baseballalmanac.com, and baseballlibrary.com.

“Sam Agnew, Batterymate for Ruth on Red Sox, Dies: He Caught Both of Babe’s Hill Victories Over Cubs in World Series of 1918,” The Sporting News, August 1, 1951, p. 30.

Several clippings from Sam Agnew’s Hall of Fame newspaper clipping file. Some have neither a title nor an author, but they include clippings from March 7, 1919, and July 29, 1937. Others from the file include:

“Troy Agnew Gives Brother Job,” February 4, 1937.

“Sam Agnew Buys Meridian,” December 21, 1939.

“Agnew’s New Deal Includes New Moniker for Meridian,” February 1, 1940.

“Sam Agnew Wants to Place Meridian Franchise in Florida,” October 24, 1940.

Full Name

Samuel Lester Agnew

Born

April 12, 1887 at Farmington, MO (USA)

Died

July 19, 1951 at Sonoma, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.