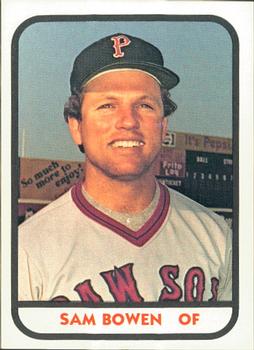

Sam Bowen

Sam Bowen was a hard man to get. Four teams — the Indians, Expos, Braves, and Angels — devoted a draft pick to him from 1970 through 1972. Each time, he chose not to sign, despite being a high second- or third-round pick of three of the teams. The Red Sox selected the right-handed outfielder in the seventh round of the June 1974 amateur draft and it was then he decided to enter the profession.

Sam Bowen was a hard man to get. Four teams — the Indians, Expos, Braves, and Angels — devoted a draft pick to him from 1970 through 1972. Each time, he chose not to sign, despite being a high second- or third-round pick of three of the teams. The Red Sox selected the right-handed outfielder in the seventh round of the June 1974 amateur draft and it was then he decided to enter the profession.

Bowen wound up appearing in just 16 major-league games in parts of three seasons (1977, 1978, and 1980) with the Boston Red Sox . His problem in signing with the Red Sox was the team’s exceptionally talented, young outfield corps: Jim Rice, Fred Lynn, and Dwight Evans. Veteran star Carl Yastrzemski was also still in the mix.

Samuel Thomas Bowen was born in Brunswick, Georgia on September 18, 1952.1 His parents were Wilbur Eugene Bowen and Vitress (Kearsey). Sam had a difficult childhood. “They divorced when I was 5. They were both alcoholics. She remarried. I had a stepfather. He was an alcoholic, too. She was single six years maybe before she remarried. I was maybe 11. He was from Michigan, in the Navy, stationed there in Brunswick at Glynco Naval Air Station, a blimp base.

“My mother was a single mom. In those days, women of the ‘greatest generation’ got shafted every which way they turned. if you were a working woman in those days and you didn’t have college — neither one of them graduated high school — the best way she could see to her two kids was tending bar because you could wink and smile and make better tips. I was very accustomed from an early age to taking care of my sister at night, babysitting and making sure we got everything done. My mom tended bar. My dad was pretty worthless. He was a good guy. He’d give you the shirt off his back. The trouble was, he’d give his shirt to everybody else, rather than paying his paltry $30 a week child support.”2

Wilbur Bowen was a World War II veteran. “He came home and went to work at the paper mill that everybody worked at in Brunswick. He was a millwright. He was probably there 12 to 15 years. A very likable guy and everybody tried to help him, but he drank himself out of a job.

“My grandfather had been a carpenter, so when he went to work construction my dad picked up his tools and he was a carpenter probably the last 15 years of his life.

“My mother shot herself in the bathroom of a bar on St. Simons Island when she was 42. I was 16, about to turn 17.

“My dad died of cancer when I was 18 or 19, but I didn’t see much of him growing up.”

Sam had two sisters, Kim, who was three years younger, and Joni, 10 years younger, the daughter of Vitress’s second marriage. Sam added, “You didn’t have to have been black and from Harlem to have been poor and to have had a less-than-stellar childhood.” Nevertheless, and fortunately, life for all three siblings turned out pretty well.

Sam grew up in Brunswick and attended Glynn Academy High School, a public high school and one of the oldest public high schools in the United States. The Cleveland Indians took first crack at him, selecting him in the 25th round of the June 1970 draft. Bowen instead chose to go to college and enrolled at Brunswick Junior College (now called College of Coastal Georgia).3

After two years, he moved to Valdosta (Georgia) State University. He made the All-Star team two years running, in 1973 and 1974.4 He both hit and pitched for Valdosta and was named MVP of the NCAA Division II baseball championship, named to the All-Star team both as an outfielder and a pitcher.5 It was then — on June 5, 1974 — that the Red Sox selected him in the seventh round and succeeded in signing him. Bowen was ready.

In all, Bowen was drafted five times. “Not something you hang your hat on,” he said.6

As he packed on the evening of June 10, preparing to head to Elmira in the morning, Bowen was watching a Red Sox home game on the television. He said he hoped to play at Fenway Park. “That’s my goal. That’s what you always dream about.”7 A few days later, he was named to the first-team All-America College Division squad, as center fielder.8

An interviewer observed, “You had to be a pretty good ballplayer to keep getting picked in the draft.” Bowen replied, “You know what? I probably got more notice playing summer and semipro ball than I did playing high school ball. There were no computers. There were no analytics. It was all about bird dogs. There were guys driving around word of mouth. Over a beer or a cup of coffee, ‘You know you have to ride over and see so-and-so. He a little bit small…’ If I heard it once, I heard it a damn thousand times: ‘He’s a pretty good player. He’s got a little talent, but he sure is small.’ All that just fueled the fire.

“I kept my nose clean. I was a ‘yes sir, no sir’ kind of guy. I fudged on the cards a little bit when you filled them out and handed then back. I was 5-8 and 160 pounds and the next thing you know I was 5-10 and 185 pounds. That would at least get them there to come see you. We played a lot of the old mill-town teams. We didn’t have a Legion team. I hooked up with a semipro team.”9 This was in the late 1960s and into 1970. “We had guys who were 40 years old. It was in a little town called Jesup, another papermill town, about 40 miles from Brunswick. There were four of us that drove from Brunswick to play with them. It was a good team. Our shortstop had played a year or two with San Diego and gotten released. My roommate, a left-hander named John Gibson, had signed with the Phillies. It was a great team. They were named after the Atlanta Crackers. Probably the most fun was going to the state prison in Reidsville. We had some great rivalries up there and a good time. They’d make you an honorary convict. You hit a home run for the ice cream. There were guys betting cigarettes on you, that you’re going to beat the hometown. That’s how I sort of ended up getting noticed.

“I was actually as good a pitcher, or better.”

Indeed, one year at college he was named an All-Star both as an outfielder and a pitcher.

“Those kind of things are sort of sketchy. There are no videos. What photos I did have, my mother actually threw away. I did not have a star-studded career at the high school level, except in summer. I was a better football player than I was a baseball player. All I had to be was tough enough to hit somebody, and I was. I just wasn’t very big at it. My 10th grade year, I broke my ankle. Had surgery. I decided just to play basketball and baseball. The coach wanted me to go out for football, but I didn’t — and he sort of shafted me. I hardly ever played my 10th grade year. I hardly ever played my junior year. And if the coach hadn’t left, we would not be having this conversation. It was my senior year that I had a chance to show at that level what I’d been showing all along since I was a kid. It was a great year.

“In high school you don’t play that many games. I was 9-1 and was averaging about 13 strikeouts a game, and hitting the ball well. You got recruited as a pitcher, but I didn’t want to only pitch in college. That’s the first time I had ever run into that, where when you get recruited they pretty much want you to be a position type player.

“In Valdosta, I got to pitch in the World Series. We went to the World Series my two years there, once in the NAIA and once in the NCAA Division Two.”

In the 1973 College World Series, he earned the distinction of playing in the fastest nine-inning game in collegiate baseball history — one hour and 38 minutes. In a game at Phoenix, Bowen pitched a one-hitter for Valdosta State, eliminating Malone College, 2-0. Just five Malone batters reached base, and the only hit Bowen allowed came when he fell down fielding a ball.10

The Red Sox placed him with the Elmira Pioneers in the Single-A New York-Penn League. He was named an All-Star outfielder in the league, batting .304 under manager Dick Berardino with 11 homers and 51 RBIs in 61 games. He recalls, “They had one all-star team for all of the A leagues, in all of the country, and I made that. I was voted player most likely to make it to reach the major leagues.”

“I was married [to Sandra Prince, known as “Hanky”] that winter,” he said, “after my first year. We were married almost seven years. We got divorced. It was amicable. Ironically, she hated baseball.” Bowen takes all the blame for the divorce — “100 percent.” He does say he had encouraged her to finish her own education and she went on to graduate school, getting a master’s degree. At one point she taught at Glynn Academy, working as a psychometrist — doing measuring and testing and evaluation. “She ended up going to Delta State,” Bowen says. Today she is married to former major leaguer Rawly Eastwick.

Despite the good year at Elmira, Bowen lost a fair amount of playing time in 1975. He struggled, hitting just .196 in 44 games for the Double-A Eastern League Bristol (Connecticut) Red Sox, and was sent down to Single-A, where he hit .184 in 12 games for Winter Haven. He had been hurt the second half of the regular season, tearing ligaments in his lower leg when sliding into home plate during a game at Tampa. He realized the Red Sox — ultimately on their way to the World Series in 1975 — were well-stocked with outfielders. “I don’t mind being traded. I want to play big league ball, I’d like to play with Boston, but with all those outfielders….”11 He took part in Florida Instruction League play that fall.

When he returned home, he said, “I got home with two one-dollar bills in my pocket at the end of that first season.” But he was offered a new contract, with a 50% raise — “from $500 a month to $750. I was in hog heaven.”

Finishing up over the winter, Bowen got his own college degree in 1975, a B.S. in education, with a minor in math.

In 1976, Bowen began to get back on track despite a hairline shoulder fracture early in spring training. He was assigned to Bristol again and played in 127 games, but he was only able to boost his batting average to .212. He homered six times and drove in 44.

He was nonetheless promoted to Triple-A Pawtucket in 1977 and performed better, even at the higher level — batting .265 in 115 games with 15 homers and 49 RBIs. The Boston Red Sox needed a backup outfielder, and he joined the major-league team in late August. Outfielders Dwight Evans and Rick Miller had collided in a game on August 19, and were both hurt. Miller needed a week off, and Evans needed surgery. Fred Lynn had a sore neck. The Boston Globe’s Bob Ryan said that Bowen was “regarded as a good defensive outfielder.”12 Defense was always his strength.

His major-league debut was disappointing. On August 25, the Red Sox had a 9-5 lead over the visiting Texas Rangers after seven innings. Lynn tweaked his left ankle earlier in the game. Bowen took over for Lynn in center field. He got up to bat in the bottom of the eighth but struck out looking against Paul Lindblad.

He got into two other big-league games in 1977. On September 5, in Toronto, the Sox had an 8-0 lead over the Blue Jays. Yastrzemski was playing left field. Manager Don Zimmer decided to give Yaz a breather, and give Bowen another taste of game action. Bowen made a couple of putouts but his one at-bat again saw him strike out looking, this time against Jerry Johnson.

Bowen appeared just one other game, on September 17 in Baltimore. He played the bottom of the eighth inning, giving Yaz a break (the Orioles were leading, 11-2), and fielded the one ball hit his way. He did not get a chance to bat. He had to wait until 1978 to get his first major-league base hit.

Bowen did not make the Boston team out of spring training, however. After a winter working at Allied Chemical, while Hanky worked at Glynn Academy, he was on a Pawtucket contract. For an offseason job, he worked eight winters at Allied Chemical. “I’d work there until the day I got home until the day I left for spring training. It was a maintenance group, a labor gang — which basically means you go from picking up trash to the things that all laborers do when work is going on inside the plant. They manufactured caustic soda. If you were to go to the EPA and research it, it’s one of the two most polluted sites in America.

“It was a starter job, but it paid much more than minimum wage. If you just go out and do manual labor, you use every muscle in your body.

“There are paper mills and chemical plants. They stink to the people driving up I-95, but to us they smelled like money.

“And I worked shutdowns as a pipefitter. Over Christmas, for those two or three weeks, the mills would shut down.” Bowen would work to maintain the pipes.

“It was an entry-level position, a starter job. But it paid much more than minimum wage and it was very physical. It could be dangerous; you’re working around chlorine gas and things like that. You did everything. We were responsible for the railroad inside the plant. I learned how to put crossties down and rails down and drive spikes. I learned how to operate heavy equipment — front-end loaders and those kinds of things. It was a good job. I enjoyed it. It was good old manual labor.”

“Back in those days, [there was no] gym thing [or] nutritionist kind of thing…No, you carried a lunch bucket, buddy. Your idea of working out was unloading a thousand 100-pound bags of soda ash out of a railroad car.”

Deep into spring training in 1978, the Boston Globe’s Peter Gammons wrote, “With some playing time in the last week, it becomes increasingly evident that Sam Bowen and Ramon Aviles are not the answers (in Bowen’s case, immediately anyways) as backups in center field and shortstop.”13 The next day, Zimmer pared the roster and Bowen was transferred to Pawtucket. He played for the PawSox through the first half of June.

On June 15, the Boston team sold Bernie Carbo to the Cleveland Indians. The next day, Bowen was recalled to Boston. He confessed to not having shown his best abilities during spring training. “I have to admit that I was very nervous this spring,” he said. “I was there playing with guys I’d just read about. Who wouldn’t be [nervous]? I didn’t have good concentration at the plate.”14 After a slow start, though, he had brought his average up to .266.

He got into six games, the first on defense at the end of the July 5 game. On July 8, he took over defensively for Yastrzemski after six innings. He was the first Boston batter in the top of the ninth, and drew a base on balls. Bob Bailey doubled and Bowen reached third base, from which he scored his first major-league run on George Scott’s groundout to third. The Red Sox lead built to 12-4.

Bowen’s first full game was on July 8 in the second game of a doubleheader. He was 0-for-3. On the 24th, he pinch-ran. On the 27th, he played another complete game, this time going 1-for-4. He struck out the first time up. With two outs in the top of the third, facing Texas Rangers starter Jon Matlack, Bowen homered for his first major-league base hit. It was the only Red Sox run of the game, a 3-1 loss in Texas. The next day, though, he was returned to Pawtucket, in order to make room on the roster for the return of shortstop Rick Burleson.

In Pawtucket, over the full course of the 1978 season, Bowen played in 89 games and hit .252 with 12 homers and 49 RBIs. He played with Pawtucket in the International League playoffs; Richmond won in seven games. Bowen was promptly brought back up to Boston.

He got into one other game for the 1978 Red Sox, on September 24. The Red Sox were one game behind the Yankees in a pennant race that ended in a one-game playoff between the two rivals. The September 24 game was played in Toronto. The Blue Jays had a 6-4 lead in the top of the ninth. With one on and one out, George Scott walked. Bowen was asked to pinch-run. After another walk, with the bases loaded, Rick Burleson hit a ball to first base, which the first baseman misplayed. Two runs scored on the error, Bowen’s the one that tied the game. Fred Kendall took over on defense, playing first base. The Red Sox won, 7-6, in the 14th.

Bowen spent all of 1979 in Triple A, playing in 125 games for the Pawtucket Red Sox. He hadn’t been “overly impressive” during the spring, wrote Kevin Dupont of the Boston Herald.15 It may have been something of a foregone conclusion, but Bowen may also have singed (if not burnt) a bridge on March 30. “Outfielder Sam Bowen, tired of sitting around knowing he was Pawtucket-bound, packed his bags, told Zimmer he wanted out and walked across the street to the minor leagues.”16

He didn’t hit as well for average, batting .235, but Bowen posted a career-high (and league-leading) 28 home runs and drove in 75 runs. He was named to the International League All-Star team. “I’m not over the hill,” he’d said in midseason, “but I’m at a crucial point in my career. I can’t bum around baseball until I’m 30 years old and then try to get a start in life. I’ve been married 4 1/2 years and my wife and I haven’t spent half of it together. We want to start a family, but that’s financially precarious on a minor leaguer’s salary.”17

In 1980, Bowen once again was assigned to Pawtucket. On May 12, he was traded to the Detroit Tigers (with a player to be named later) for Jack Billingham. It was initially reported that he had refused to go, however. He was “bothered by a bad leg” and “refused to go to Detroit because he was afraid he’d get there and wouldn’t get paid if the strike hits.”18 Bowen later told the same reporter that he had welcomed the trade — “I was so excited I couldn’t wait to get to Detroit” but when, “just being honest,” that he had told Tigers GM Jim Campbell that he was hurt, Campbell canceled the trade in anger at the Red Sox for trading him a less than fully healthy player.19 Bowen says, “I was traded and un-traded to Detroit in less than 24 hours.”

Due to injuries in Pawtucket, Bowen was needed. He played in 89 games for Pawtucket, the same number of games as in 1978. His batting average dipped again, to .229 with 14 homers and 35 RBIs.

He was called up to Boston on September 2. He played in seven games, collecting base hits (both singles) in the first and last games. He was 2-for-13 (.154) with two walks. They were his last two hits in the majors; he finished with a .136 average (three hits in 22 at-bats) and a .240 on-base percentage. He had one home run, one run batted in, and three runs scored. In the field, he handled 23 chances without an error. Bowen might have played in a few more games, but had to leave the team for a while due to the death of his father-in-law in Waycross, Georgia.

Bowen was kind of in roster limbo. Referring to the 1980 trade that was canceled, he said in January 1981, “After all this happened, the Red Sox were noticeably cold toward me… Where this leaves me, I don’t know…I’m disappointed, but I’m not bitter, over what happened last year. They can take your job, but they can’t take your sense of self-worth away from you. But, I admit, they almost did that last year.”20 He continued playing at Pawtucket in both 1981 and 1982.

Bowen was clear about where he stood. Before his 1981 season with Pawtucket, the Red Sox had dropped him from their 40-man roster, and he’d gone through the minor-league draft without being selected by another big-league team. He’d signed with Pawtucket, but his annual pay was $15,000 and not the $22,500 it had been when he was on Boston’s roster.21 Frankly describing himself as a “marginal ballplayer,” Bowen told Peter Gammons, “The goal of any ballplayer is to find out just how good he is. In my mind, I have yet to prove to myself that I cannot play in the big leagues, and I’d hate to go home and spend the rest of my life thinking that I might have been able to be there.”22 He was proud, he said, “to have been good enough to get this far. Of all the people who play baseball, how many have? I am not Fred Lynn. I’m not Carl Yastrzemski…I’ve thought about hanging my spikes up…I just want the opportunity afforded other marginal players. I want to find out how good Sam Bowen really is; I think I can play in the big leagues.” He knew that, for one reason or another, he hadn’t made the kind of impression that some others had. “Coaches like aggressive players; I realize that. I’m not a loud, outgoing person. I’m extremely competitive, but I’m not outwardly aggressive.”23

In 1981, he had a solid year, playing in 131 games, homering 27 times (second in the league), and driving in 64 runs. His average was .243 (OBP .353). He took part in the famous “longest game” — the 33-inning game played by Pawtucket — batting behind Wade Boggs in the lineup. The game was suspended at 4:09 A.M. on April 19, and one could see the glimmer of dawn as the team left McCoy Stadium. “Look at that,” Bowen said, “We might as well have sunrise services.”24 Bowen threw out a runner at the plate in the top of the 32nd inning, and almost won it in the bottom of the inning with a tremendous drive that the wind pushed back onto the field. The game was halted then and resumed on June 23. The PawSox won in the 33rd. The day before, on June 22, he hit two homers and drove in all six runs as the PawSox beat Charleston.

Coincidentally, Bowen had played in the shortest game in collegiate baseball, and the longest game in professional baseball.

He did acknowledge that he had asked to be traded.25 That didn’t come to pass.

Bowen was named to the International League All-Star team. Peter Gammons came to think of him as a major-league player “probably…buried in the wrong organization.”26 But he’d still not been claimed in the minor-league draft, perhaps because he was 29 years old as the year ended, “typecast as a Triple-A player.”27

In 1982, after playing winter ball in the Dominican Republic, Bowen started the season with Pawtucket and played in 60 games, but finished it with the Charleston Charlies — another International League team, a Cleveland Indians affiliate. He’d been sent there at the start of August “on a contingency deal.”28 If the Indians liked how he played, they would have the option to buy his contract. He played in 27 games for Charleston. His combined stats showed him with 12 homers and 29 RBIs.

Looking back, Bowen says, “I got to Triple A pretty quickly. I played six years in Triple A. I found out that all these guys were saying, ‘Hey, this guy’s 26, 27 years old. What the heck is he doing hanging around?’ And then you’re that 26, 27, 28 years old and you think you’re a half a step and 30 or 40 AB’s from being able to play in the big leagues.”

His 1982 season with Pawtucket was his last in professional baseball. The team optioned him to Double-A Bristol at the end of the year. He was released on the first of February 1983. He was frustrated and bore some anger. He felt the Red Sox had misrepresented his health at the time of the Billingham trade to the Tigers, causing Detroit to void the deal. The Red Sox had portrayed him as the culprit. It left a bad taste in his mouth. He didn’t know what his future would hold.

“I was very fortunate after nine seasons of playing. I was an education major. I wanted to teach and coach and change the world. Work with kids that didn’t have a whole lot and give them some guidance and a little social consciousness kind of stuff. I found out that the inmates are running the asylum. There was no money to be made. I interviewed for everything from being a Border Patrol agent to civil service to an industrial banker and I ended up going to work for Nike.”

His first position was with Fuller-O’Brien, a paint, forestry, and industrial products coating company based in San Francisco, but with a plant in Brunswick. He interviewed with them and got a position in sales, based in Tennessee. He worked for them for six months, long enough to know it wasn’t what he wanted to do. A buyer for a department store chain told Bowen the Nike rep was leaving. “I didn’t know what a manufacturer’s representative is. I followed up on it and I was very fortunate to hook on. I was a traveling shoe salesman. I was selling to all kinds of sporting goods stores, footwear stores, department stores. You had an account base. Malls weren’t nearly as prevalent as they became. The harder you wanted to work, the more money you could make. I could out-work the other guy. It was very competitive. I enjoyed it. I made a good living there. I was with them for about 16 years.”

In 1985, he married Brenda Henderson, to whom he’d introduced by the office manager at the Nike offices in Nashville. “I wasn’t dating anybody. I was learning a whole new industry. … The office manager kept saying, ‘Sam, you’ve got to lighten up. You’ve got to have a social life. I know this young lady who runs with my sister.’ They were runners. We were introduced, started dating, and then a year or so later got married. Brenda and I have been married 35 years. We have three children. Maggie is 32 and we have twins, Eric and Emily — that are 29.

“After Nike, I was with Adidas for six years, the same kind of work. They just paid better. It was still commission-based. I enjoyed that.” His territory was Kentucky and Tennessee. He had about 125 accounts, but the lion’s share of his business came from the top five or six accounts.

One of those accounts — a six-store operation called Sport Seasons — hired him to do their marketing and running the footwear operation. He was glad to have a position that allowed him to get off the road and be at home, since his children were getting older and he wanted to be there for their sports events and the like. That job ended up lasting about six years.

He left in 2012, when the company had a very difficult year financially. They wanted him to take a large pay cut, but instead he decided to resign.

“I had never quit a job in my life,” he says. But he adds, “I didn’t have any other mountains to climb or dreams to fulfill. I never called it retirement, because if something had come along. I don’t miss work. I put in a lot of hours for a lot of years.”

Bowen was inducted into the Valdosta State Hall of Fame back in 1997. In March 2013, he was inducted into the Glynn County Hall of Fame back in his hometown of Brunswick.

Last revised: February 8, 2023 (zp)

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Donna L. Halper and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Bowen’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 His name no doubt reminded some of Sam Bowens, who played right field for the Baltimore Orioles and Washington Senators from 1963 through 1969. That was Samuel Edward Bowens and no relation.

2 Author interviews with Sam Bowen on December 21, 2019 and March 20, 2020. Unless otherwise indicated, all direct quotations come from these interviews.

3 He’d initially gone to Clemson. “I went to Clemson out of high school. Hoyt Wilhelm’s brother Bill was the coach there and he was probably one of the finest men I ever met. Just a father figure kind of guy. I would have had a chance to start as a freshman. It was about 300 miles from home. I was miserable. I was immature. I was a good student, a low-A, high-B student. I lasted that first semester and I went in and apologized and went back home. I withdrew just before the semester was over and immediately enrolled in junior college there at home. My dad had passed away right before I left. I lived with my grandfather after my mom died, and he died two weeks after my dad.” Having seen him decline to sign after three previous drafts to this point, just five months later the California Angels made him their second-round pick in June 1972. One assumes they thought they had a shot; teams don’t like to essentially lose a draft pick. But Bowen was determined to stay in school. The reason he hadn’t accepted any of the offers, he later explained, was “There just wasn’t enough money [offered] to make it worth stopping my education.” See Vic Fulp, “Tag of Streak Hitting Is Growing on Bowen,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, July 8,1979: 26.

4 Dan Couture, “Cougars Land 4 On NAIA Team,” Columbus Daily Enquirer (Columbus, Georgia), May 24, 1974: 16.

5 Associated Press, “Valdosta Tops Eckerd,” Augusta Chronicle (Augusta, Georgia), May 27, 1974: 10.

6 “In my senior year, I was a first-team All-American. George Digby was the scout who signed me. I had nobody to sit in with me, so I asked Coach [Tommy] Thomas to sit in with me in the negotiation in the gym at Valdosta State. He [Digby] was chewing on one of those little old-timey cigars. ‘Welcome aboard…blah blah, blah. We’d like to offer you $7,000 and get you signed up and get you on your way.’ I asked for a few moments to speak with my coach. Coach Thomas said that was a good offer. He hadn’t done that before. I was a humble guy and it was hard to talk about myself, saying I was a good player, but I had had a great year. We went back in and I sheepishly said that I felt that the year I had was commensurate with my having a little bit more money than that, and that I would like to throw a number back at $10,000.”

Digby responded, as Bowen tells it, saying, “I think what we’re offering is very fair.” He added, “You know I could get up and walk out of the room….” Bowen says, “My heart sank. I didn’t want him to walk out of the room. But he said, ‘I think 10 will do it. Let’s just get it done.’”

7 Murray Poole, “Bowen Heads for Elmira, N.Y., After Signing with Red Sox,” Brunswick News (Brunswick, Georgia), June 11, 1974: 6.

8 Murray Poole, “Poole Shots,” Brunswick News, June 14, 1974: 6.

9 His actual height is 5-foot-9.

10 “Countdown to the Series: Don’t Plan on Many Two-Hour Games,” Lewiston Morning Tribune (Lewiston, Idaho), May 21, 2019. https://lmtribune.com/sports/countdown-to-the-series-don-t-plan-on-many-two/article_5cb93912-4aac-52f0-bb59-ec332e6cc594.html

11 Murray Poole, “Unlucky Season for Bowen,” Brunswick News, July 23, 1975: 10.

12 Bob Ryan, “Hernandez Released,” Boston Globe, August 21, 1977: 86.

13 Peter Gammons, “Torrez Gets Battered; Evans Reinjured,” Boston Globe, March 24, 1978: 57.

14 Larry Whiteside, “Jackson ‘Concerned’ About Slump,” Boston Globe, June 20, 1978: 27.

15 Kevin Dupont, “Sox Bench,” Boston Herald, March 28, 1979: 37.

16 Peter Gammons, “Lynn Encounters Throwing Problems,” Boston Globe, March 31, 1979: March 31, 1979: 22.

17 Tim Horgan, “They’re Down on the Farm,” Boston Herald, June 22, 1979: 27.

18 Peter Gammons, “Owners Make Some Concessions,” Boston Globe, May 14, 1980: 25.

19 Peter Gammons, “Going Nowhere?” Boston Globe, June 28, 1981: 65, 69.

20 Murray Poole, “Bowen’s Future Uncertain with the Boston Red Sox,” Brunswick News, January 9, 1981: 8.

21 Peter Gammons, “Going Nowhere?”

22 Peter Gammons, “Going Nowhere?”

23 Peter Gammons, “Going Nowhere?”

24 Dave Anderson, “No Winners,” State Journal-Register (Springfield, Illinois), April 21,1981: 9.

25 Jack O’Hara, “Sports Talk: Sam Bowen,” Brunswick News, July 21, 1981: 5.

26 Peter Gammons, “How They Gonna Reap ‘Em Down on the Farm?,” Boston Globe, April 10, 1982: 24.

27 Peter Gammons, “Rainey May Need Relief,” Boston Globe, April 20, 1982: 39.

28 Peter Gammons, “Houk Was Happy to Go to Stanley,” Boston Globe, August 3, 1982: 32.

Full Name

Samuel Thomas Bowen

Born

September 18, 1952 at Brunswick, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.