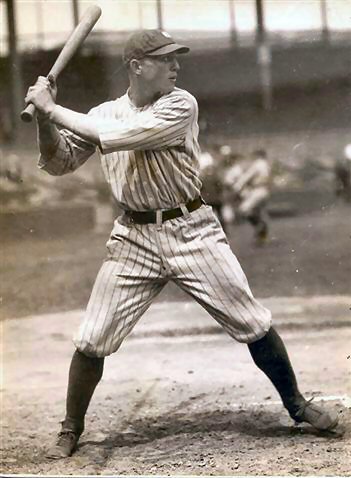

Sammy Vick

Sammy Vick was noted as the only player to ever pinch-hit for Babe Ruth. Vick had been the regular right fielder of the Yankees in 1919, but New York had purchased Ruth from the Boston Red Sox over the winter and Vick lost his starting job. But he said he had an opportunity to pinch-hit for the man who replaced him.

Sammy Vick was noted as the only player to ever pinch-hit for Babe Ruth. Vick had been the regular right fielder of the Yankees in 1919, but New York had purchased Ruth from the Boston Red Sox over the winter and Vick lost his starting job. But he said he had an opportunity to pinch-hit for the man who replaced him.

He told the story himself in a handwritten letter to Professor Marshall Smelser of Notre Dame.1 Writing from his farm in Pope, Mississippi, in 1972, Vick wrote:

My greatest day came one day, in N.Y. with the bases loaded, the score tied, and Babe’s turn to bat. The height of the ambition of fans was to see such a setup. They were almost taking the top off the stand. There was a lull in the game. Babe did not climb out of the dugout. He had hurt his wrist and couldn’t go up to bat. Poor Miller Huggins was up against it. He looked up and down the bench several time. I was sitting on the end of the bench. Each time he got to me his eyes dropped, and he looked back over the lineup again. Finally he said, “Sam, get your bat.”

I began to breathe again, picked out my bat and started up to the plate. The announcer said in a loud voice, “Vick, batting for Ruth.” When it dawned on the crowd what was happening, you could have heard a pin drop. It seems five miles up to the plate. The stillness was frightening. But on the way down inside of me, there was a reaction: “That’s just what you think.” I then blacked out and don’t remember anything until I slid into third base with a triple. With one ‘po’ country boy feeling good.

No date was supplied. Vick never mentioned what team was the opponent. It would have had to be in 1920, the only time Ruth and Vick were on the same team. Vick would have picked up three runs batted in on the play, but he had only 11 RBIs all year. There was a game, though, on May 18 at the Polo Grounds. Cleveland was the visiting team and Vick did have three RBIs in the game. But Ruth didn’t play at all in the game; Vick was the only right fielder and he had four at-bats. He also walked once. He had two hits, a single and a double. He hadn’t played since May 7.

Ruth was out on doctor’s orders with a mild strain. Vick substituted for him – perhaps at the last minute, and perhaps Huggins had looked up and down the bench, though Vick was the logical choice. It was his second time up, in the third inning, with one run already in, that Vick came up with the bases loaded, and cleared them with an extra-base hit, hitting the left-field fence on one bounce. It was a double, not a triple as he recalled 52 years later. Whatever base he reached, he did drive in all three runners. The score was 4-0, and the Yankees were on their way to an 11-0 victory. It was almost as good a story. According to Baseball-Reference.com, Vick appeared as a pinch hitter 18 times that year, batting for pitchers 16 times and once each for catcher Truck Hannah and first baseman Wally Pipp.

Vick was from Mississippi, born in Central Academy, Batesville, Panola County, on April 12, 1895. His parents were Hugh and Lilly Vick, both native Mississippians who farmed for a living. At the time of the 1900 census, there were four children in the family: Eula, Samuel, Atheral, and Mary. Eula had the name Wilson Vashti Vick in the 1910 census, but Atheral – a boy – stayed the same. Mary was no longer with the family at that time, perhaps having died.

Sammy attended Mount Olivet, Coutland High School, and both Mississippi A&M and Millsaps Colleges.

Samuel Bruce Vick’s pro career began in 1917, and it was a fast route to the big leagues for him. He had apparently not played much as a child, for it was written that he “learned the game” as a student at Millsaps College in the state capital, Jackson. He was a multisport athlete there, at baseball, track and field, and basketball. He was listed as 5-feet-11 with a playing weight of 166 pounds. He played in the Delta Auto League, where he was spotted by a former Memphis Chick, now a scout, Bill Robertson, and signed to a Memphis contract.2

With Memphis in the Southern Association, Vick played in 126 games and batted .322 with a couple of homers. Scout Bob Gilks recommended him to the Yankees, and was lavish enough in his praise that New York sent Memphis $4,200 and two pitchers.3 He’d been making $150 a month with Memphis. He was to report to New York after Memphis’s season.

The Yankees had a way they broke in their new recruits. Before each game the recruits and regulars played five innings against each other. Vick did this for several days before his major-league debut on September 20, 1917, against Cleveland, in New York.4 He singled, drew a base on balls, and scored one run in four plate appearances. He appeared in ten games, getting ten hits in 36 at-bats (.278). He had two runs batted in, one of them in the second game of an October 3 doubleheader. His double drove in Wally Pipp with the tying run, and a sacrifice fly brought in Bill Lamar with the winning run.

Vick played in only two games in 1918, both in April. He was 2-for-2 with an RBI in the first game and 0-for-1 in the other. With the First World War under way, Vick had submitted an application on February 22 to become a pilot in the United States aviation corps.5 He trained with the team and started the season, but on May 3 received a call from his draft board to report for duty with the Army. He was one of 12 Yankees to be called to serve in 1918. Vick served with the 301st Cavalry, and apparently traveled far. The Baltimore Sun reported him in Siberia, perhaps as part of the American Expeditionary Force Siberia.6 But the newspaper had jumped the gun. Vick was scheduled to be sent there, but was rerouted instead to Camp Kearny, California, with the 74th Field Artillery and learned in early December that he would be mustered out.7

On February 22, 1919, Vick married Lois Mildred Monteith. He joined the Yankees on March 26 and played with the team throughout the season, appearing in 106 games.

In his second game, on April 28 against Philadelphia, he hit two triples, scoring the winning run after hitting a 12th-inning triple. Two days later, also against Philadelphia, “The Tennessee Thumper” led off the game with a homer off Mule Watson into the left-field bleachers. It was one of only two homers he hit in the major leagues. The other was a grand slam in the second game of an August 7 doubleheader against the visiting St. Louis Browns, Allan Sothoron the victim. It was Vick’s first day back after being out more than two weeks.

Besides his two home runs, Vick hit 9 triples and 15 doubles in 1919, and drove in 27 runs, batting at a .248 clip. He scored 59 runs.

After his first full season of play at the big-league level, and with the Yankees finishing in third place, Vick was looking forward to 1920. But the Yankees bought Babe Ruth from Boston.

Vick was quick to send in his contract. Babe Ruth was saying he wouldn’t show up unless he got a piece of the purchase money. Ruth and Duffy Lewis were seen as the mainstays of the Yankees outfield, with either Ping Bodie or Vick in the third spot. Vick did pinch-hit in the bottom of the tenth on April 25, and won the game with an RBI single, but he was pinch-hitting for the pitcher, Mays, not for Babe Ruth. On the 18th, substituting for Ruth, he drove in the three runs as described above. On August 16, when a Carl Mays pitch fractured Ray Chapman’s skull in the fifth inning (leading to Chapman’s death), Vick pinch-hit for Mays in the eighth, and rolled out.

There was another story that Vick himself told in later years. We can’t find anything close to verifying it. He wrote Prof. Smelser that it was in Washington, where there was a terrible background for hitters and “I couldn’t hit in that park with a bass fiddle for a bat.” He said that Walter Johnson pitched one of the games and a “fellow named Shad” pitched the other. As he told it, the Yankees were shut out both games, and he himself had a horrible day. “I went to the plate seven times and struck out seven times.” He felt really lowdown until someone “dropped his arm over my shoulder and said, ‘Don’t mind that, boy. When the Babe strikes out five times, they don’t see you.’” It was Del Pratt and he thought it was the kindest thing any ballplayer did for him. He drew a lesson from it: “Always say a kind word when a fellow is down. You never know how much good it will do.”8

Vick was asked about playing for Miller Huggins. He said of himself that one of his weaknesses was that he was too shy and timid. As a calling card, he didn’t draw. (“They want a nut that will bring the bugs through the gate.”) But, he said, “the other side no one suspected, when aroused I was a little vicious.” After a game in Cleveland, when he was the goat, he’d no sooner gotten into the clubhouse than Huggins “jumped on me. He was working me over good, and finally called me a timid player. That’s when the other side exploded, before you could bat your eye, I was up on top of him and said, ‘You damn little runt, if you wasn’t so little, I’d stomp you in the floor before anybody could get me off of you.’” He suddenly realized this was his manager and backed off fast. The next day Huggins approached him and said, “What you did yesterday did me more good than anything you have done since you have been up here. I didn’t know that was in you.”9

As the season worked out, Bodie got more work and so did newcomer Bob Meusel, but Vick remained for the full season as a fifth outfielder and got into 51 games. His average was .220 with just 11 RBIs and 21 runs scored. The Yankees finished third again.

And on December 15, the Yankees worked another deal with the Red Sox – this time a four-for-four trade. Del Pratt, Muddy Ruel, Herb Thormahlen, and Vick went to Boston and the Yankees got Harry Harper, future Hall of Famer Waite Hoyt, Mike McNally, and Wally Schang. Vick was characterized by the New York Times as “a hard hitter and an improving fielder, but has failed to live up to his early promise hereabouts.”10

Perhaps a change of scenery would do him good? Vick took a while to sign his contract, and was dubbed a holdout, and when he did come, he arrived late – saying that an explosion in his hometown had held him up. He was also noticeably favoring one knee over the other – not a good sign.11 Six days later the Boston Globe reported that Vick would probably be sent home, his knee being in such bad shape that he shouldn’t have bothered to report.

Vick returned, his Red Sox debut coming on June 2 and his first eight appearances were as a pinch-hitter. He drove in a run in his second game, on June 3, singling in the winning run in the bottom of the ninth, breaking a 6-6 tie with the Indians. And he drove in two the next time at bat, on June 7, his two runs tying the game, with Del Pratt’s sacrifice fly winning it.

Vick appeared in 44 games, batting .260, drove in nine runs, and scored five. He worked most often as a pinch-hitter; only 14 of the 44 games saw him take the field.

At some point before the year was out, Red Sox owner Harry Frazee sold his contract to Toronto.12 Vick’s time in the majors was over.

He didn’t play much for Toronto – 50 games, batting .233. On March 2, 1923, he signed with the Memphis Chicks. He hit much better – the Southern Association was Single-A ball – batting .290 and played a very full 148-game season. His biggest hit of the year came on August 1, a bases-loaded hit in the bottom of the ninth over the drawn-in left fielder’s head to win a game against Birmingham.

In 1924 Vick became manager of the Brookhaven (Mississippi) Truckers in the Class D Cotton States League. It was a six-team league; the Truckers finished fourth. Vick played himself and hit .322, in 97 games.

The young skipper (he was only 29 with Brookhaven) managed the Laurel Lumberjacks team for parts of 1925 and 1926. Laurel was another Cotton States League team which finished fifth each year (the league had grown to eight teams starting in 1925.) Vick signed at almost the last minute, just in time to get into the May 8 game. Starting on July 2, he became interim manager – but was kept on and helped pull the Lumberjacks up to fifth with a “phenomenal finish,” in the words of the Biloxi Daily Herald. 13

In 1926 Vick was named manager again to start the year, though he suffered a case of mumps that kept him away from the team during spring training. For the most part, he played outfield but was also seen as a pitcher in some games, and as a catcher at times.

On August 16 Vick’s contract was sold to the New Orleans Pelicans, to report on the 20th. He was the league’s leading batter at the time, with a .391 batting average.14

Vick played in at least 32 games for the Pels, but had accumulated enough at-bats before leaving Laurel that he was the Cotton States League batting champion with a .376 average. He was a batting champion for one team, and on a pennant-winning team for another (the Pelicans won the Southern Association flag). Vick contributed during the stretch drive; he was hitting .340 as of September 18. The Pelicans faced off against the Dallas Steers in the Dixie Series, won by Dallas. Vick hit .276 in 29 at-bats.

Vick played for New Orleans in 1927 and 1928, and pitched at times for the Pels, too, such as on May 20, 1927, when he came on in relief and threw the final six innings. Sometimes his contributions were a little painful, such as the game against Memphis on the afternoon of June 23 at Heinemann Park. It was the bottom of the 11th inning, neither team having scored in the game, when Vick came up to bat with the bases loaded. He was beaned, but thus scored the winning run.15 The Pelicans won another pennant, but were again vanquished in the Dixie Series, this time by Fort Worth.

Vick got off to a slower start in 1928 but finished with a .304 average. New Orleans finished a distant third.

He started the 1929 season with New Orleans but was batting only .235 after the first 14 games. He was sold to Dallas but was returned a few days later and was immediately sold to Chattanooga. He is listed as hitting a combined .333 in 104 games.

Vick’s last season in baseball was 1930. He played for the Memphis Chicks and hit .330 in 95 games. He was purchased early in 1931 by Mobile, but appears never have to played.16

Vick later said that an injury, and a little stubbornness, did him in when he was with the Yankees. He believed in himself and thought he had had the potential. He had the ability to just tap the ball and see it carry, even to the outfield wall. He could have become what Huggins asked him to work on, a pinch-hitting specialist. “But the ignoramus that I was, I wanted no part of that. I wanted to feel that bat bend and undress a third baseman. If I had not gotten hurt, I might have come around to it. If I had, I should have been one of the great hitters of baseball. I do not know of any other player that could tap line drives against the wall. The point here is that Huggins saw it. He tried to get everything out of a player he could.”17

The year he left the game, Vick reported working as a public-school teacher at the time of the 1930 census.

Before retiring from the game, Vick had used some of his earnings to buy a farm near his father-in-law’s, and raised peaches and cattle. Wife Lois Vick said, “Sammy was a natural artist. He painted many beautiful pictures as a hobby. He also taught school for many years and was a fine Sunday School teacher. Unfortunately, all that had to stop when glaucoma blinded him.”

Vick’s later years were probably not happy ones. Though he had a large family, by the time he was 85 years old he had lost both his sight and much of his hearing, which “denied him his greatest pleasure – watching baseball on TV.”18

Vick died in Baptist Hospital in Memphis at the age of 91, on August 17, 1986. He was survived by three daughters and three sons, 22 grandchildren, and 15 great-grandchildren.19 He is buried in Batesville.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Vick’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Baseball Necrology, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Thanks to J.G. Preston.

Notes

1 The original of the letter is in the Smelser Collection at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and a copy is in Vick’s player file. The punctuation has been altered slightly here.

2 Information about Millsaps and Robertson both come from an unidentified 1917 clipping in Vick’s Hall of Fame player file.

3 New York Times, July 7, 1917.

4 New Orleans Times-Picayune, September 21, 1917.

5 Washington Post, February 22, 1918.

6 Baltimore Sun, December 5, 1918.

7 Watertown (New York) Daily Times, December 9, 1918.

8 Letter to Marshall Smelser, April 7, 1972, in Vick’s Hall of Fame player file. It was only in 1920 when Pratt, Ruth, Johnson, and Vick could have all been in the same game and there was never a time when the Yankees were shut out twice in succession, and the most times Vick ever struck out in any one day was three times in the second game of a July 13 doubleheader in New York against the St. Louis Browns. As it happened, Babe Ruth did strike out five times in that doubleheader, so it perhaps was the date Vick had in mind. Pratt may well have offered him words of consolation. Vick alluded to the same 7-for-7 day in another letter to Smelser on April 18.

9 Letter to Marshall Smelser, April 11, 1972.

10 New York Times, December 16, 1920.

11 Boston Globe, March 23, 1921.

12 Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 16, 1921.

13 Biloxi (Mississippi) Daily Herald, September 20, 1925.

14 Baton Rouge Advocate, August 17, 1926.

15 New Orleans Times-Picayune, June 24, 1927.

16 The Sporting News, February 12, 1931.

17 Letter to Marshall Smelser, May 28, 1972.

18 Jim Ogle, “Where Are They Now?,” Yankee scorebook, 1980, 21.

19 Jackson Daily News, August 20, 1986.

Full Name

Samuel Bruce Vick

Born

April 12, 1895 at Batesville, MS (USA)

Died

August 17, 1986 at Memphis, TN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.