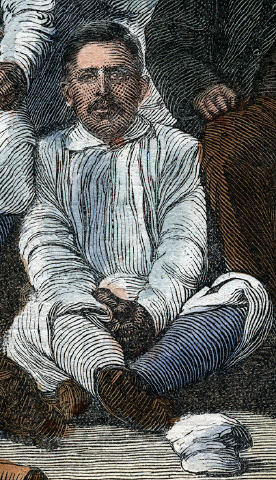

Sandy Nava

Sandy Nava, the first Mexican-American in major-league history, was quite a bit younger when he entered the major leagues than the encyclopedias indicate, ten years in fact. He was actually 22 years old at the time of his debut with the Providence Grays, as a backup catcher for Monte Ward and Hoss Radbourn in 1882.

Sandy Nava, the first Mexican-American in major-league history, was quite a bit younger when he entered the major leagues than the encyclopedias indicate, ten years in fact. He was actually 22 years old at the time of his debut with the Providence Grays, as a backup catcher for Monte Ward and Hoss Radbourn in 1882.

Another confusing aspect in identifying Nava is the array of names used to identify him. He was born Vincente Simental, identified by his mother’s maiden name. His father’s identity is left to conjecture. When Nava was about seven, his mother married an Englishman named Irwin; thus, Vincente Simental became Vincent Irwin. He gained a reputation playing baseball in San Francisco under the name Sandy Irwin at the turn of the 1880s, then joined the Providence Grays in April 1882 and became known as Vincent Nava, a marketing effort to internationalize his surname and thus increase his appeal. That’s the name that stuck for the rest of his life. Today, he is referred to as Sandy Nava by baseball fans.

Vincente Simental was born on April 12, 1860, to Josefa Simental in San Francisco, California. The 1860 U.S. Census shows three-month-old Vincente living with his sister Octaviana, 4, also born in California, and Josefa, 30, no occupation noted. Adrian Burgos Jr. in his work Playing America’s Game identifies Simental as her maiden name citing Mario Longoria’s research. No father is listed in the household. Shortly after Vincente’s birth, the family relocated to Mexico. According to the 1870 Census, Josefa had two more children, Guillermo and Juan born in Mexico, in 1862 and 1865 respectively. Josefa hailed from the state of Durango, Mexico. It’s been speculated that his father’s name may have been Nava, hence his use of it upon joining Providence and keeping it thereafter.

Soon after Juan’s birth, Josefa and family returned to San Francisco where she married William Irwin, an English-born druggist about her age. He had immigrated to the United States sometime prior to 1860, settling in Shasta, California, before relocating to San Francisco. William and Josefa had three children: Samuel, 1868; Abraham, 1870; Thomas, 1872. Josefa passed away in 1879. Nineteen-year-old Vincent then took a residence with his brother Guillermo, now known as William, across the street from the rest of the family. In the city directory that year, Nava is listed as a blacksmith, apparently playing baseball as a side endeavor. He also played cricket, perhaps with the Occident club.

San Francisco was the hub of the West Coast well into the twentieth century. Tens of thousands of Americans and immigrants settled there after gold was discovered near Sacramento in 1848. California’s first professional league, the Pacific Base Ball League, was formed in 1878 and was naturally centered in the state’s economic base, San Francisco. The league included four teams, the Eagles, Renos, Californias and Athletics. At age 18, Nava played for the Renos and Athletics. In 1879, he played for the Renos and Oakland Knickerbockers of the same league. He also was a member of the Occident baseball club of San Francisco, a teammate of future major leaguer Jerry Denny. At the time, Occident was more known for its cricket club than its baseball nine.

That year, the rival California League was first organized, lasting through 1893. Unfortunately, organizers were unable to secure grounds in San Francisco, so the league based itself in Oakland, a serious detriment since the city’s population was only about 14% of that of San Francisco. In October, the National League Cincinnati Reds and Chicago White Stockings toured the West Coast, further promoting the sport in California. This was Nava’s first exposure to the top-flight east coast game.

In 1880, the California League finally secured the use of a ballpark in San Francisco and was thus able to lure better talent. The Knickerbockers moved into the CL, as did Nava for a time. Jim Whitney pitched for the club, his only season on the West Coast. Nava also caught for the San Francisco Stars and Renos of the Pacific Base Ball League. Though young, Nava gained a reputation for working with the fastest and the best pitchers of the West Coast, such as Whitney and Charlie Sweeney. In the era of rudimentary gloves and masks, a tough, durable catcher was valuable. At the time, the catcher typically played well back of home plate, perhaps upwards of twenty feet. According to Mario Longoria, one of the aspects of Nava’s game that stood out was his aggressive and successful approach at chasing down pop flies.

In 1881, Nava played with the San Francisco Athletics of the California League. That year, Denny, a transplanted New Yorker who grew up in a San Francisco orphanage, joined Providence in the National League. He was one of the first San Franciscans to enter the top tier of baseball on the east coast. The following winter, he returned on a barnstorming trip with several other major leaguers, including one of Providence’s main pitchers, John Montgomery Ward. Ward had been with the club since 1878 and was one of the main reasons Providence won their first championship the following season, leading the league with 47 wins under manager George Wright. Ward even managed the club for 32 games in 1880. Providence’s new manager for 1882 was George’s brother Harry Wright. In January, Ward petitioned Wright and the club directors on behalf of Nava and a couple other Californians. Denny and sportswriter Henry Chadwick sung the praises of the catcher as well.

The Boston Globe reported, “Sandy Irwin – the California catcher – whom Ward wishes the Providence club to engage for next season – greatly distinguished himself in the recent twelve-inning game between the Renos and Nationals in San Francisco. He then faced Ward for the first time, and his record of nineteen put out and six times assisting, or a total of twenty-five chances accepted without an error, is well deserving of the highest praise, and it is more wonderful from the fact that he played the last six innings with a sprained ankle.” Nava apparently hopped around for much of the game but remained in the lineup. Naturally with a catcher like that, Ward felt confident pitching to him; he would take any physical abuse the position necessitated. Nava made of the most of his opportunity to impress an east coaster. However, the Providence directors had to mull the subject over. Some felt a Latin player was a liability; others cited his potential drawing power. The team finally acquiesced and brought Nava, Charlie Sweeney and an outfielder named Brown east for a tryout. The club wired their potential new catcher $50 to cover his expenses.

Sandy Irwin landed in Providence in early April, and fans were soon informed that he would now be known as Nava. The reason for the name change may have more to do with Providence’s desire to market their “little Spaniard catcher” than any pressing reason from Nava. “Irwin” didn’t sound very exotic. Wire reports introduced Nava to the eastern baseball fans: “The Spaniard who is to catch for [Providence] is 21 years old, weighs 153 pounds, and is a trifle shorter than [starting catcher Barney] Gilligan, but heavier built, especially around the shoulders. He has the dark olive complexion and distinctive features of the race, and is a quiet, intelligent fellow. His name is Vincent Nava, the name Irwin, adopted by him, being that of a step-father.”

This wasn’t the typical ethnic background a major leaguer during the early 1880s. Nava was, in fact, the first Mexican-American accepted into the majors. As a man of Latin heritage, he had been preceded in the top eastern leagues by Cuban Esteban Bellan, who played for three seasons with Troy and New York in the National Association from 1871 to 1873. Indeed, Nava’s racial background was a topic of conversation and curiosity. He has been referred to at times as Spanish, Cuban, Indian, Italian, Portuguese, black, or mulatto. His ethnicity sparked a great deal of conjecture. Adrian Burgos asserts that Nava was among the first, if not the first, to openly straddle the line between races in the major leagues—clearly identified by the fans and all in the game as “nonwhite.” Luckily, there were few loud, overt or violent altercations during his career over his racial background. As researchers have noted, not even Cap Anson caused a fuss.

Since Nava was among the first West Coast ballplayers to join the eastern major leagues, and hence was a complete unknown, it may be safe to assume that no catcher before had seemingly popped out of nowhere to wow the crowds with his fielding exploits. Harry Wright only granted Nava a tryout, no guarantees. Nava took that to heart and put forth his best effort. The newspapers in April and May were flooded with his praises. On April 16, 1882, the Syracuse Sunday Herald reported, “Some thought that the nine was a terribly experimental one, and were inclined to the belief that too much confidence had been placed in Ward when he was authorized to sign with the Californians, but now they are willing to admit that in Brown and Nava we have two rare jewels. Nava (Irwin) played in one game this week, catching Ward’s perplexing curves with astonishing coolness. He does not wear a mask, standing up fearlessly to his work. His return ball is remarkably swift, while his throwing to second base is precision itself. His batting is free and sharp.”

After a game versus Yale on April 22, an article read, “Nava…played without a mask, and was struck by a foul tip. He pluckily finished the game, however.” The Daily Inter Ocean admired his work as well. On May 9 it commented, “Nava caught a magnificent game throughout.” Two weeks later on May 25, it highlighted, “Nava supported Radbourn faultlessly and superbly;” A week later, he still impressed, “There were no special features save the plucky catching of Nava with a badly swollen finger.” Nava never would hit at the major-league level, but for now his fielding expertise earned him a roster spot. According to the Daily Inter Ocean, “Vincent Nava, who is better known in California baseball circles as ‘Sandy’ Irwin, has been on trial with the Providence club, and having proved himself to be an excellent catcher, was last week added to the list of men regularly engaged for the season.” He had secured his roster spot. Brown, however, didn’t make the club and would have to make the long trip home. Sweeney would only appear in one game for the club in 1882, but would return the following year to replace Ward.

Nava made his major-league debut on May 5 in a 17-2 victory over Worcester, catching the tricky Hoss Radbourn. He went 3 for 6 with a double and two runs scored but also made two errors. On May 26, he broke his finger in the sixth inning catching Radbourn and left the game. As noted above, Nava still caught despite the sore digit on May 31 and again on June 2, although he had to leave the latter game in the eighth inning with a throbbing finger. On June 4, his turn in the catching rotation came up again, but he was ailing from his broken finger and refused to play. Tim Manning, normally an infielder, had to cover behind the plate as the club’s main catcher Gilligan was hurt as well. Ward didn’t want to pitch to Manning, declaring that the main catchers were the only ones suitable to the task of fielding his curves. After Manning booted a ball in the first inning, Ward worked in a sour and erratic fashion the rest of the game. The club directors met after the game and fined both Ward, $50, and Nava, $10. Nava was penalized for previously telling management that he was ready to go, but pulling out as the game neared.

On June 19, Providence arrived in Detroit for a three-game series. In appreciation of the Grays catcher’s work behind the bat, the Detroit Free Press altered the words to the song “H.M.S. Pinafore” for a tune that pretty much sums up Nava’s entire major league career, acknowledging his inability to hit – seldom making a “clash” with his “ash” – but praising his expertise behind the plate – Nava “hardly ava . . . let a ball go by.” On July 27, Nava was fined $100 by the club for “conduct prejudicial to the interests of the association. Nothing is stated specifically, and the players, if they choose, can prevent undue publicity.” Someone did talk though; the excessively large fine was for drunken behavior at the club’s hotel. Second baseman Jack Farrell was fined a larger sum, $200, because he committed several errors the day after the incident.

A backup catcher, Nava only appeared in 28 games in 1882, hitting a meager .206. His work impressed though and Providence inked him for the following year before the current season ended. Nava and much of the Providence club played exhibition contests throughout October. At the end of the month, he and Jerry Denny took off for home. By mid-November, they were playing for the Reno club. Their return contests attracted some of the largest crowds of the year.

On April 7, 1883, a correspondent for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat declared, “Denny and Nava, of the Providence club, have reached the Atlantic seaboard after a tiresome trip of eleven days’ duration from San Francisco. Both were in admirable physical condition, having been playing ball all winter on the Pacific coast.” During the next couple springs and during exhibition contests throughout the seasons, Nava played several infield and outfield positions so he’d be ready to cover others in case of injury during the regular season: “Nava has been playing second base on the reserve nine, and astonishing every one by his perfect and lively work.” In total, he was only called on to cover three games in the outfield, six at short, and one at second base.

Nava stuck with the club the entire season but only appeared in 29 games, batting .240. After the season, he played some exhibition games with the Grays and then joined Ted Sullivan on a barnstorming tour through the south, mainly in New Orleans, Mobile and Dallas. After a game on October 18, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat commented, “The best feature of the game was the pitching of [Charlie] Sweeney and the catching of Nava, the little Spaniard being cheered time and again for his plucky and brilliant work.” In December, the same paper boasted, “Little Nava covered himself with glory in the field, catching and throwing like a perfect machine.” Likewise impressed, Sullivan courted Nava for Henry Lucas’ new Union Association, offering the catcher $2,500 to jump leagues. Nava turned down Sullivan’s offer, and he left New Orleans to rejoin Providence in March 1884.

Providence’s 1884 pennant-winning season is famous for the exploits of Hoss Radbourn, winner of a record 59 games. Nava caught 27 games (playing in seven others), many of them for the club’s other pitcher, Charlie Sweeney, before the pitcher deserted the club in the middle of July. That season, Radbourn preferred pitching to Barney Gilligan. Perhaps it was the manager’s decision, as the team favored Gilligan’s production with the bat; Nava hit a pathetic .095, managing only eleven hits, all singles, in 116 at bats. The June 7 game against Boston typified his reputation as a good-field, no-hit backup. With Sweeney on the mound, “Nava gave beautiful support, putting out nineteen men, making three assists and not an error.” It was the day Sweeney set the record with 19 strikeouts. With the stick, Nava went 0 for 3 with two strikeouts, and he hit into an 8-3-5 triple play in the fifth inning.

Providence won the pennant by 10.5 games mainly due to Radbourn’s right arm, but Nava was released before it was over. His last appearance occurred on September 5. He had been hitless in his last four games, which in part led to the dismissal. The team took off on September 13 for a month-long road trip, leaving him and Cyclone Miller behind. The pair joined the Fort Monroe, Virginia, military team at the beginning of October. Miller luckily caught on with the Philadelphia National League club for a game on the 9th, but Nava was left twisting. On August 22, he had received a telegram from Henry Lucas offering the catcher $600 to join St. Louis in the Union Association for the rest of the season. The message even carried a personal plea, “Sweeney says come.” To his detriment, Nava proved loyal, giving the telegram to the Providence directors and rejecting the offer. The club didn’t return the loyalty, releasing him too late in the season to catch on with another major league club. Nava also played some games for the Old Point Nationals, a Norfolk, Virginia, club. During one exhibition contest, the Nationals loaned him to the Baltimore Orioles. The catcher must have impressed because by December he was listed as a member of the Baltimore squad of the American Association.

Nava quickly became a favorite in Baltimore in 1885. After a preseason game, the Sporting Life declared, “The center of interest was Nava, who played a fairly steady game considering it was his first appearance in facing [Baltimore pitcher Hardie] Henderson, and did a few clever plays that captured the plaudits of the shivering audience, notably a quick diving catch of a lost foul fly and some sharp, steady work in a beautiful double play. His tenacity in holding onto the ball when keeled over by the base runner he put out and his ‘keeping his head’ and driving the ball to third, thus completing the play, was a very cool, plucky piece of business.” He even hit well as the season opened, as the Sporting Life again noted, “From year to year the batting strength of some players [vary], and the present season is no exception to the rule. Nava, for instance, is an illustration of this. He was once the poorest of the poor – couldn’t hit a full moon – but now the little giant saunters demurely to the plate and cracks the sphere for doubles and singles, and usually when they are most needed. . . . He is so diminutive and selects such a large bat that he generally appears at the plate looking like a chipmunk hiding behind a sapling.”

Nava was released in July after only appearing in eight games. By August, he found a job driving a taxi. Baltimore appealed to him; he spent the rest of his life there. He also found a slot playing for a local amateur club called Patterson. Unsigned as the season approached, Nava considered returning home to San Francisco, but he ultimately stayed in Baltimore. In May, the Sporting Life noted his reconsideration: “Vincent Nava, the little Spanish catcher, has changed his mind about going to California to join the Alta club, and will, for the present, remain in Baltimore, unless he should secure engagement.” Baltimore needed a catcher at the end of June, so Nava joined the club for two games on the 28th and 29th. With that, his professional baseball career ended. In 101 major league games, he batted .177 in 345 at bats.

In February 1887, Nava was signed by Danbury of the Eastern League but was released before the season started without a tryout. He settled in Baltimore, working as an upholsterer and never marrying. On June 15, 1906, Vincent Nava passed away at age 46 from uremia, a disease related to alcoholism, at City Hospital. At the time of his death, he worked as a bouncer at a saloon located near Hamilton Pier, a tough part of town. He was interred at the local Trinity Cemetery, a segregated “nonwhite” burial ground. The cemetery’s land was later seized for highway construction. Nava and others may reside under the city’s paved streets.

Note

There was a Mexican family living next to the Simental family in the 1860 U.S. Census in San Francisco. It’s curious because the former family’s name is similar to “Nava” but its inconclusive, as the handwritten name could be translated any number of ways.

Sources

Great appreciation is extended to Mario Longoria for exchanging phone conversations with me and providing valuable information and insight which proved vital to this Nava project. Mr. Longoria’s search for the elusive Sandy Nava, or whatever his name might be, has taken him across the United States and abroad.

Baseball-reference.com

Boston Globe, 1882, ‘84

Burgos Jr., Adrian. Playing America’s Game: Baseball, Latinos, and the Color Line. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 2007.

Chicago Tribune, 1882

Cleveland Herald, 1882-84

Cleveland Leader, 1884

Daily Evening Bulletin, San Francisco, 1879, ‘82

Daily Inter Ocean, Chicago, 1882

Daily Republican-Sentinel, Milwaukee, 1882

Detroit Free Press, 1882

Familysearch.com

Galveston Daily News, Houston, 1883

Milwaukee Sentinel, 1886

Nemec, David. The Great Encyclopedia of 19th Century Major League Baseball. New York: Donald I. Fine Books, 1997.

News and Observer, Raleigh, North Carolina, 1884

New York Clipper, 1882

New York Times, 1882

North American, Philadelphia, 1886

Olean Democrat, New York, 1882

Retrosheet.org

Rocky Mountain News, Denver, 1884

Spalding, John E. Always on Sunday: The California Baseball League, 1886 to 1915. Manhattan, Kansas: Ag Press, 1992.

Sporting Life, 1885-87

St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 1882-87

Syracuse Sunday Herald, 1882

Full Name

Vincent P. Nava

Born

April 12, 1850 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

Died

June 15, 1906 at Baltimore, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.