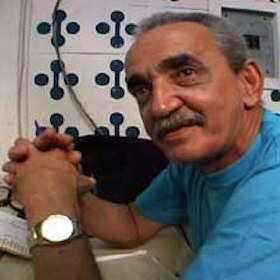

Sigfredo Barros

“There is no baseball off-season in Cuba,” declares Sigfredo Barros Segrera, long-time sports journalist for the Cuban Communist Party news service Granma, available in print, in Cuba, and online versions for the rest of the world.

“There is no baseball off-season in Cuba,” declares Sigfredo Barros Segrera, long-time sports journalist for the Cuban Communist Party news service Granma, available in print, in Cuba, and online versions for the rest of the world.

Barros was born on November 14, 1945 in the provincial capital city of Santiago de Cuba, the second largest city in the nation. It is in the eastern province also called Santiago de Cuba, part of the province known as Oriente before 1976.

His father, a banker and a local radio announcer, and his mother, a hair stylist, were both educated through the Cuban system.

As a child, Sigfredo studied at the elementary school Escuela Activa in Santiago de Cuba and attended the Frank Pais Institute for high school. A good student, Sigfredo left his home province to attend the University of Physical Culture and Sports Science Manuel Fajardo in Havana. “Manuel Fajardo” is known internationally for providing sports education and training to teachers, coaches, and sports specialists in Third World nations.

Like most youngsters in Cuba, he remembers his father giving him a glove and ball when he was 4 or 5 years old. He also recalls his father taking him to a game at Estadio Guillermón Moncada in his home town of Santiago. The matchup was between Havana’s Almendares and the Elefantes de Cienfuegos. Sigfredo recalls seeing the great Cienfuegos pitcher Camilo Pascual and says that he “will never forget Pascual’s curveball.”

He also has been a lifelong New York Yankee fan, but, he says, his father never did like the Yankees. He was impressed with the history of the team. Mickey Mantle was his favorite player. Barros recalls that Mantle could run, field, and hit with tremendous power.

A friend from his hometown encouraged Sigfredo to consider journalism as a career. He was and is still an avid reader, a student of both news and sports, and these interests continue to serve him well in his work as a journalist.

Barros started working at the Granma newspaper in 1971. He started out covering a variety of sports for Granma including swimming, water polo, cycling, fencing, and rowing. It was not till later that he started covering Cuba’s favorite game – baseball. There is nothing equivalent to the BBWAA (Baseball Writers Association of America) in Cuba. For years, Barros had been the primary baseball writer at Granma, along with a shifting series of baseball writers at Juventud Republic.

His daily entry in Granma is essentially a recap of all eight games played in the Cuban National Series. The daily column includes the daily line scores. The newspaper costs one Cuban peso, or about five cents. Only one game is televised each night; he picks up the information about the games over the telephone.

He does write occasional essays, including a memorable and loving tribute to Conrado “Connie” Marrero on the occasions of his 100th birthday and his passing just before his 103rd birthday in April 2014.

As a journalist in socialist Cuba, he faces challenges unknown to his contemporary American counterparts. He has very limited access to the Internet. He works the phone for information. He does not own a car, so his visits to the ballparks are brief as he returns home in the early innings to meet his deadline for the morning paper.

Granma is the organ of the Communist Party of Cuba, so Barros must carefully consider what he can write. His journalistic style is a clear and simple narrative, but devoid of the commentary and analysis that one finds in the US media.

The passion that he has for baseball comes through in his conversations more than in print. He is an astute observer of the politics of Cuban baseball and often critical of decisions informed more by political interests than the need to field the best team to represent his country.

In 45 years, Sigfredo Barros has covered a lot of baseball. He regards Omar Linares, the legendary Cuban third-baseman, as the best player he has seen. He also liked Orestes “Minnie” Miñoso and the passion with which he played. He wonders why Miñoso, who died in 2015, has not made it into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Covering baseball has allowed him to travel outside the island, visiting countries including Japan, South Korea, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Holland, Spain, and Panama.

One of his favorite stories is about the first World Baseball Classic (2006), when Cuba made it to the finals against Japan. He shares that “it was a big surprise for everybody, because it was the first time since 1959 that Cuba played against stars in the big leagues. To beat the Dominican Republic, in the semifinals, against Bartolo Colón on the mound, and Papi Ortiz and Albert Pujols at the plate was really great.” His friend and Cubaball “jefe,” Kit Krieger, recalls visiting with “Siggy” at the Palacio O’Farrill hotel on the eve of his departure for Puerto Rico, where the first games were played. Everyone in Cuba was worried that the Cubans would not be competitive against Japan, the Dominican Republic, the U.S., and Venezuela, but Barros told Krieger that the team was a good one and had a chance to win the tournament.

Barros wants his readers to understand the game more deeply and he writes with that goal in mind. His challenge is to write honestly and impartially, not favoring one team. His readers will ask him “which is your team?” because he never writes about one team in particular. He writes about the 16 teams in the National Series. His favorite part of being a journalist is writing a story about the game or tournament, commenting on all that happened, good and bad. His least favorite stories are when he has to go to the airport to meet the team on its return to Cuba, because all the players and team are anxious to be at home, and nobody wants to talk.

One of his favorite players to interview is Yulieski Gourriel, National Team star infielder and widely considered the most talented player in Cuba. Yulieski, one of three sons of Lourdes Gourriel, a star in the Cuban National Series in 1980, played with his home province of Sancti Spiritus until moving to Havana’s Industriales team beginning in the 2013-14 season. Barros compliments him for being very polite and for “knowing how to talk with a journalist.”

Barros covered the historic visit of Cuban major-league players to Havana in December 2015. He relates that Jose Abreu told him, “I am still a Cuban farmer kid” and that it was great to be able to come home to visit. He also visited with Joe Torre, who told him that he was very happy to visit “the country of baseball.”

In Havana, the Parque Central hosts the Esquina Caliente (the “Hot Corner”), a local gathering spot for passionate fans who spend hours discussing baseball, both local and international. Barros is something of a local celebrity and “something like a rock star.”1 He often drops by to visit with La Peña de Parque Central (Havana’s society of baseball historians) only a few blocks from his modest apartment in Central Havana and talk about the current state of béisbol de Cuba.

For him, the current state of baseball in Cuba is uncertain. In 2015, over 100 players emigrated to the Dominican Republic, or the U.S., to play for more money. But that has led to the deterioration of the Cuban teams. He hopes that the “blockade will end, and that Cuban players can play in the big leagues, and then return to Cuba as well.” Barros would like baseball fans outside of Cuba to “know that baseball in Cuba is a sport, it is a religion, a problem of state.” He goes on to say, “We, the Cubans, talk in baseball terms: if you are ‘in 3 and 2’ that means you are in a difficult situation. If ‘she takes you out on the bases’ your wife has seen you with another woman. In Cuba, baseball has colored all aspects of life.”

Barros has two adult children, who are very proud of their father and his work as a journalist. His son Alejandro is a graduate in Language and English literature. His daughter Anelore is a lawyer, who studied international diplomacy and speaks Chinese. Ani spent two years studying and working in Beijing. Barros tells us that they both enjoy baseball and watch the games on television.

What would he do if he were not a sportswriter? Barros replied that he would be an engineer, as he loves to work with numbers and statistics.

He makes a fine sportswriter. You can find his stories on the Granma website.

He also appears as himself in Stealing Home: The Case of Contemporary Cuban Baseball, commonly known as Stealing Home, a 2001 PBS television documentary about Cuban baseball defectors directed by Robert Anderson Clift and Salomé Aguilera Skvirsky.

Last revised: February 23, 2016

Sources

Correspondence with Sigfredo Barros, March, 2015 through February 2016.

Correspondence with Kit Krieger, December 2015 through February 2016.

Havana Times.org

Peter Bjarkman, “Cuban baseball authorities are facing a most difficult situation”, Bjarkman’s Latino and Cuban League Baseball Page, MLB blogs, September 23, 2014.

Notes

1 Ben Strauss, “High hopes for Cuban baseball, but challenges ahead,” New York Times, March 4, 2013.

Full Name

Sigfredo Barros Segrera

Born

November 14, 1945 at Santiago, Santiago (CU)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.