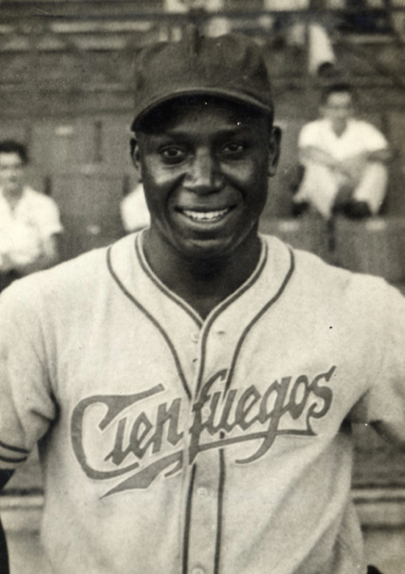

Silvio Garcia

Silvio García was a shortstop and pitcher who played in Mexico, Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Canada, and his native Cuba, as well as the American Negro League and organized minor leagues, from 1931 to 1954. Known for his powerful right-handed line-drive swing and rifle arm, he won two batting championships in the Cuban League and ranked first in RBIs for the Mexican Red Devils in 1942. He is considered by many to be the finest shortstop in the history of Cuban baseball. Branch Rickey, before signing Jackie Robinson for the Brooklyn Dodgers, made two attempts to sign García to break the color line in Organized Baseball, and Horace Stoneham, owner of the New York Giants, may have had similar intentions.

Silvio García was a shortstop and pitcher who played in Mexico, Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Canada, and his native Cuba, as well as the American Negro League and organized minor leagues, from 1931 to 1954. Known for his powerful right-handed line-drive swing and rifle arm, he won two batting championships in the Cuban League and ranked first in RBIs for the Mexican Red Devils in 1942. He is considered by many to be the finest shortstop in the history of Cuban baseball. Branch Rickey, before signing Jackie Robinson for the Brooklyn Dodgers, made two attempts to sign García to break the color line in Organized Baseball, and Horace Stoneham, owner of the New York Giants, may have had similar intentions.

Silvio García Rendon was born on October, 11, 1914, in Limonar (formerly known as Guanacaro), Cuba, in the province of Matanzas, to Fausto García and Pastora Rendon. He lived in the same dwelling with his father, his brother Ruben, and two sisters, Paulina and Mirta, from 1932 until 1943, paying $15 a month in rent. At some point during this time, his mother died. As a young teenager, Garcia already stood 6 feet tall and weighed a stocky 195 pounds, and worked as a carpenter’s apprentice. He played baseball for the independent semipro Toros de Paredes of Matanzas, as well as during a stint in the Cuban armed forces that followed, from which he received his army license with a perfect record. While the young man “was inclined to amusements,”1 he and his family enjoyed the finest of reputations for morality and honesty among their neighbors and local professionals.

Professional baseball in Cuba dates back as far as 1878, with what came to be known as the Cuban Winter League becoming the focal point of the sport. This small circuit of three to five teams, narrowly centered in Havana, often featured outstanding major-league and Negro League players. But the stock-market crash of 1929 as well as the violent political insurrection against the controversial government of President Gerardo Machado resulted in the total absence of American players from the abbreviated 1931-32 Cuban Winter League. This afforded opportunities for younger Cuban players like the 17-year-old García, who began his professional career for the Habana Leones of legendary player-manager Miguel González, hitting .258 in 66 at-bats and playing third base as well as the outfield.

García did not participate in the brief 1932-33 season. The playoff series was put off to the fall and ultimately canceled after the final collapse of Machado’s regime; the turmoil that followed prevented a 1933-34 season as well. He resumed his participation in the Cuban Winter League as a pitcher for the Marianao Tigres in the 1934-35 season. Once again, the lack of American transplants combined with the defections of the better Cuban players to other environments left a weakened league that afforded inexperienced youngsters a chance to demonstrate their abilities. García appeared in six games, pitched 30⅓ innings, and finished with a 1-2 record and an ERA of 2.47.

In the 1935-36 season he appeared in five games as a pitcher, completing three of them, and also played shortstop; he came to bat 131 times, hit seven doubles and one triple, and batted.275, second-best on the squad behind Aurelio Cortés. García established his talent in the 1936-37 season, starting 13 games for Marianao and finishing with a record of 10-2. This time there was no lacking for competition – many of the finest Negro League players participated in Cuba that winter. Among them, only future Hall of Fame standouts Raymond “Jabao” Brown, who won a league-record 21 games for Santa Clara, and the Tigres manager, the great two-way Cuban player Martin Dihigo, had more wins that year. Like his manager, García was a regular in the lineup even when not pitching, but he hit only .234 in 188 at-bats. Nevertheless, the Tigres caught the Leopardos on the final day of the season to force a three-game playoff. After losing the first game to Brown, the Tigres rebounded to win the second one, 4-2, behind the stellar pitching of García, who allowed eight hits and two runs. The Tigres subsequently won the championship via a complete-game victory by Dihigo.

Like many of the top Hispanic and Negro League players of the time, García was lured to the Dominican Republic in the summer of 1937 by the promise of a hefty salary from minions of the notorious dictator Rafael Trujillo, who had combined the Licey/Escogido ballclubs of Santo Domingo into one, and renamed it – like the nation’s capital itself – Ciudad Trujillo. Under an intense military presence, García’s team – which included the likes of Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Cool Papa Bell, Pancho Coimbre, and fellow Cuban Lázaro Salazar – won the Dominican Summer League championship game over the Aguilas Cibeañas, a team owned by the Generalissimo’s political rivals and featuring Dihigo, Chet Brewer, and Luis Tiant Sr. García led the league in hits (38) and doubles (14) while batting .297.

In addition to his winters spent in Cuba, and his one summer in the Dominican Republic, García also found the time to play in Venezuela from 1932 to 1937 for both the La Gaira and Pastora clubs of the Federación Venezolana de Béisbol, the first league in Venezuela and the organization that eventually became the governing body of the sport in that country.

García returned to Cuba to play for Dihigo and Marianao once again in the fall of 1937. Marianao failed to repeat the heroics of the previous campaign, although the team did make history by appearing in the first night game ever played in Cuba, on December 21, against Almendares at La Tropical Stadium. The experiment was a failure, and night games were tabled until the mid-1940s. For the season, García hit .295 in 156 at-bats. In the summer of 1938, he ventured to Mexico for the first time to play for the Veracruz Aguilas of the Mexican League. He hit .349 with a .491 slugging percentage, and won 10 games on the mound against only two defeats, finishing second in the league in ERA behind Dihigo.

García joined the Almendares club for the 1938-39 season, but it was not a good year for the beloved Blues, as they finished with a record of 20-34. He is listed in the statistical record books as an outfielder, which is understandable given the presence of Negro League great and future Hall of Fame inductee Willie Wells, who took over the lion’s share of the shortstop duties. García hit .293 in 187 at-bats and appeared in seven games as a pitcher as well, completing two with a 1-4 record.

García returned to Veracruz in the summer of 1939, and ventured in the fall to Puerto Rico, where he pitched for Ponce in the fledgling Liga de Béisbol Semiprofesional de Puerto Rico (LBSPR). He led the circuit with an ERA of 1.32. Despite his excellence on the mound, it was around this time that Garcia commenced the transition from pitcher to position player. Carlos Santiago, a teammate with Ponce, claimed that García hit a Mayaguez batter on the head with a pitch, almost killing him, and it so affected him that he vowed never to pitch again. Another rumor circulated that García had been struck by a line drive to his arm while sitting in the dugout during a game, which put an end to his pitching career. Regardless, García did not play in the 1940 summer Mexican League campaign, and he was primarily a shortstop from this point on, although he continued to pitch intermittently in the early 1940s, mostly in Mexico.

In the 1940-41 season, García played for Santa Clara in the Cuban League, and just missed winning the batting title with an average of .314, losing out by two points to Salazar. That summer García returned to Mexico, this time playing for the Mexico City Diablos Rojos, and had one of his best seasons; he hit .366 with a .518 slugging percentage, led the league in hits (159), and scored 102 runs while competing against markedly improved competition. By this time the Mexican League had been subsumed by millionaire businessman Jorge Pasquel, who had purchased the Aguilas of Veracruz in order to move them to a bigger market in Mexico City and create an intracity rivalry with the Diablos Rojos. Pasquel stacked the deck in favor of his new team, now named the Azules, by signing players including Dihigo, Salazar, Wells, Josh Gibson, Ray Dandridge, Leon Day, and Double Duty Radcliffe; in 1941 the Azules finished with a record of 67-35 and won the league title.

The 1941-42 season began García’s association with Cienfuegos, known over the years as the Petroleros, the Loros Verdes, and finally the Elefantes. The team from the southern coast of Cuba actually played its home games at La Tropical Stadium in Havana to attract larger crowds; by the end of his career, García would be closely identified with Cienfuegos. García’s first year with the team was certainly his best in Cuba – he won the batting title with an average of .351 and led the league in hits (60), runs (24), and home runs (4). In 1945-46 he helped the team win its first league title since the 1929-30 season.

The spring of 1942 also marked the second year in a row that the Brooklyn Dodgers made Cuba and La Tropical their spring-training destination, an event that would have implications for García soon afterward. In the meantime, he went 8-for-21 at the plate for a team of Cuban all-stars in a five-game exhibition series against the Dodgers, won by the locals 3 games to 2. Brooklyn manager Leo Durocher was impressed enough by what he saw of García that he told general manager Branch Rickey, “I saw a player and if we had brought him back he would have a chance to play in the big leagues. Marty Marion can’t carry his glove.”2 Armando Vasquez, who played in the Negro Leagues and winter ball, corroborated this version of events. He said Durocher had seen García play shortstop and heard him say, “If they ever let the black people play in the big leagues right now, I would sign that fellow. He would be the shortstop for the Brooklyn Dodgers.”3

Returning to Mexico for the 1942 summer season, García hit .364 and led the league with 83 RBIs for the Diablos Rojos. The 1942-43 campaign in Cuba was played without the benefit of any appearances by American players; wartime travel restrictions prevented their participation. García hit .303 for Cienfuegos, but his club brought up the rear in the three-team circuit.

In 1943, at the age of 28, Garcia did not have his best season in Mexico, hitting only .301, which may have been an unfortunate turn of events, as it was at this point that Rickey first received permission from the owners of the Brooklyn Dodgers to begin pursuing “colored” players to integrate Organized Baseball. Acting on the tip from Durocher, Rickey commissioned a private background report in April of 1943 from an agency in Havana – the subject was one Silvio García. Rickey then met covertly with scout Tom Greenwade at the Biltmore Hotel in Kansas City to direct him – in total secrecy – to travel to Mexico in May to look at the Cuban shortstop.

Greenwade recounted his trip to Mexico with several variations over the years. In one retelling, he met with Jorge Pasquel and his brother Alfonso, and the two men brandished pistols in what proved to be a very effective method of deterring the Dodgers from signing any popular players away from their league. In another version, Greenwade simply came away unimpressed by García, and did not turn him in to Rickey. “He couldn’t pull the ball,” Greenwade said. “He was a right-handed hitter – everything went to right field.”4 Of course, that was one of García’s strengths, as noted by many who saw him play – he was one of the strongest hitters to the opposite field in the game. Greenwade also may have believed that García was a prankster who did not take the game seriously enough. “He’d stick his head out of the dugout and the Mexican fans would throw limes at him,” Greenwade told Rickey.5

Regardless of Greenwade’s opinion, there is considerable evidence that Rickey remained interested in García after his scout returned from his clandestine assignment in Mexico, and that he dispatched the Dodgers’ legal counsel, Walter O’Malley, to Cuba after the Mexican season had ended, armed with a $25,000 letter of credit and instructions to sign García. Upon arriving in Cuba, O’Malley discovered that García had been conscripted into the military, and gave up the chase. The background check supplied to Rickey seems to support this version of events, stating that since García was 28 years old he had to register for a second call of Cuban compulsory military service.

A final version of events from Cuban baseball historian Edel Casas has Rickey meeting with García in Havana in 1945 and heaping upon him the same type of abuse he later inflicted on Robinson in an attempt to determine if his recruit could withstand the storm of racism he would be bound to confront should he be the one chosen to integrate the sport in America. Rickey asked, “What would you do if a white American slapped your face?” “I kill him,” García replied.6

There is certainly reason to question the veracity of each version of these events – it appears that Cuba did not have military conscription in 1943, for one – or at least the extent of Rickey’s interest in García. Rickey was a moralizing teetotaler who, it is safe to say, would not have been impressed by García’s reputation as a hard drinker with a somewhat virulent temper when under the influence. Also, it is questionable whether Rickey would have chosen a dark-skinned Latin American as his crusader for racial justice, as it would have made the task at hand that much more difficult to accomplish. Both the language barrier and the fact that García was not an American would have militated against the chances of success for Rickey’s grand mission. “It’s tough enough for a colored boy if he can speak the language,” one of Rickey’s assistants said. “So it’s going to be doubly tough if he can’t.”7

However, Walter O’Malley steadfastly maintained that he indeed traveled to Cuba in 1943 for the express purpose of signing García for the Dodgers. Milton Gross wrote in the New York Post in 1954 that the idea was born in a meeting of the Dodgers directors in 1943 that was held to discuss the wartime shortage of players. Rickey suggested that the Dodgers plumb Latin America for talent, and that he had one particular player in mind – Silvio García. George McLaughlin, president of the New York Trust, a creditor of the Dodgers, was familiar with García, and gave the thumbs up to pursue a “colored” player.

Regardless of the Dodgers’ interest in García, he may have had another suitor. Gross was told by O’Malley that he encountered Jimmy Walker, the ex-mayor of New York who was associated with the Giants at the time, on the flight to Havana, and that when informed, Rickey told O’Malley to get to García before Walker could. Ultimately, Gross confronted Horace Stoneham, owner of the Giants, with his suspicions that the Giants had in fact pursued García in 1943. Asked why he had kept this information private, Stoneham replied, “I wanted a baseball player, not a sideshow. Would I have mentioned it if he were white? Did it make me a bigger man because he was a Negro? I was trying to help my team, not myself.”8

Some American players were permitted to travel to Cuba for the 1943-44 season, among them a young catcher named Roy Campanella, whom Greenwade had discovered on his covert visit to Mexico in the summer of 1943. García, of course, returned for the season completely unaware of what was going on behind the scenes. He hit .329 for Cienfuegos to no avail, as they finished third in the four-team circuit.

In the summer of 1944 García returned to Mexico to play for Pasquel’s Veracruz Azules club, which began the season managed by Rogers Hornsby, whose tenure lasted just a short time before the volatile veteran inevitably butted heads with his employer. García hit .314, led the league in steals with 31, and drove in 83 runs. Negro Leagues great Willie Wells was still playing in Mexico at the time, and explained his preference for playing there: “We live in the best hotels, we eat in the best restaurants, and we can go anyplace we care to. We don’t enjoy such privileges in the U.S.”9

The 1944-45 season was interrupted by a hurricane that hit Cuba on October 18, damaging the playing field and scoreboard of La Tropical Stadium. Cienfuegos, managed by the legendary Adolfo Luque, could manage only a third-place finish despite an appearance on the mound by its manager, at the age of 54. García continued as the shortstop, batting .254.

García returned for another season at Veracruz in 1945, and put on an impressive display of speed and power, leading the league with 40 stolen bases, and finishing third in home runs with 15. Veracruz featured a number of Cuban players, including Ramón Bragaña and Pedro Formental.

The 1945-46 season was a particularly strong one in Cuba, as it represented the first postwar professional baseball. The four teams’ rosters swelled with Negro Leaguers, returning Americans, both from the war and Mexico, and many native Cubans who had been playing in Organized Baseball. This was the season in which Cienfuegos, managed by Luque, won the championship.

García added one more country to his baseball résumé in 1946, and it was an important one; he eschewed Mexico in favor of the United States to play for the New York Cubans of the Negro National League. Playing alongside a 20-year-old Minnie Miñoso as well as veteran Negro Leaguers Dave Barnhill and Barney Morris, García hit .318/.360/.533. His batting average was good enough for fifth in the league.

That fall García became embroiled in the ongoing controversy caused by Jorge Pasquel’s persistent attempts to induce major-league players to jump their contracts and play in Mexico. When the Cuban Winter League ignored the edict of Baseball Commissioner Happy Chandler to shun the jumpers, an alternative Cuban league called the National Baseball Federation was established to afford a home for both Cuban and American “players of good standing” within Organized Baseball. While there was nothing preventing García from participating in the established league, he chose, for unknown reasons, to play in the Federation and manage the Matanzas club, which won the championship under the split-season format. García hit .344 and led the league in hits (55) and steals (23).

While the Federation played its games at La Tropical, the established league christened the new Gran Stadium, which was larger and featured a much stronger level of play. In fact, the 1946-47 Cuban Winter League season has come to be considered the most glorious year in the history of professional baseball in Cuba, as Almendares, behind Luque, rallied from far behind to catch Habana, managed by Gonzalez, on the last day of the schedule, while fans packed the glistening new stadium.

The Federation was a disaster that collapsed after one year, but it was made irrelevant anyway as a result of a pact between the Cuban Winter League and Major League Baseball in which the former agreed to rid itself of the jumpers and surrender sovereignty in exchange for reinstatement to Organized Baseball and a conduit to a steady stream of young American players.

García returned to the New York Cubans in 1947, joining Miñoso as well as another fellow Cuban, Claro Duany, who hit .429. For his part, García batted .333 and led the Cubans to the league championship as well as victory in the Colored World Series against the Cleveland Buckeyes, champions of the Negro American League. He hit .389 in the series. He also appeared in all four East-West Negro League All-Star games held in 1946-47. García also played an important part in the development of Miñoso; he roomed with the young man from his own home town of Matanzas, easing his adjustment to the United States as well as acting as a buffer for some of the unexpected and brutal racial intolerance Miñoso encountered. He taught Miñoso both baseball and social skills. “I’ll never forget; he was the guy who taught me to play third base because I used to play third base like I was catching – block the base like home plate. He taught me there. He taught me how to be a high-class expensive dresser. I had great respect for him. We were good, good buddies.”10

The next year saw another challenge to the hegemony of the Cuban Winter League. Some players did not see the return to the good graces of Organized Baseball as such a positive development, and sought better pay for their labor. They decided to form a union and another new league, the Liga Nacional, again resorting to playing its games at the abandoned La Tropical. The new league made an auspicious debut, but before long succumbed to financial pressures, with the Santiago club dissolved and its players merged onto the rosters of the remaining teams. Still, there was much talent on display, including pitcher Sal Maglie, who won 14 games for the generically named Cuba club, and Ray Dandridge. For his part, García returned to Cienfuegos (managed by Lefty Gomez) of the established league, and hit .292, but his team finished last in the standings as Almendares won the championship.

It is not known why García abandoned the Negro Leagues in 1948 and returned to Mexico, where he played for the Diablos Rojos of Mexico City, as theoretically the integration of Organized Baseball had opened a window of opportunity for black players. It is quite possible that García, at the age of 33, was considered to be past his prime. He hit .315 for Mexico City, and finished his career with a batting average of .335 in Mexico.

The Liga Nacional folded after one year, bringing unity to Cuban baseball once again. There was a veritable flood of imported players in 1948-49, including Monte Irvin, Dave Barnhill, Al Gionfriddo, and Hank Thompson. Cienfuegos again brought up the rear, and García managed only a .250 batting average.

In 1949 García once again forged new ground, playing in the independent Canadian Provincial League, based in the province of Quebec. As Jackie Robinson discovered in 1946, racial tolerance was far greater in eastern Canada than in the U.S., and many Latin players, including Puerto Rican great Pancho Coimbre and fellow Cubans Claro Duany, Adrian Zabala, and Rodolfo Fernandez had played for Sherbrooke. García joined the Athlétiques and promptly led the league in hits with 112, while Duany contributed 99 RBIs.

Back in Cuba that winter, the Cienfuegos club challenged Almendares for the title, staying in contention until the final week before falling short; García hit for an average of .260, and he played third base predominantly for the first time in Cuba.

In 1950, at the age of 36 – when it appeared that his skills were beginning to erode – García rebounded with one of his finest years, decimating Provincial League competition. He won the Triple Crown by hitting .365 with 21 home runs and 116 RBIs. The league, now accepted back into Organized Baseball and graded Class C, featured many black players who were considered too old to play in the United States. García proved that thinking to be premature in his case, as he continued his revival in the Cuban League that winter, leading the circuit in hitting for the first time in nine years, with a .347 average, and in stolen bases with 17, despite missing a month with a broken hand. He was named co-MVP along with the 34-year-old pitcher Adrian Zabala of the champion Habana Leones.

Havana sportswriter Pedro Galiana took note of García’s performances in the 1950-51 season; in his depiction of one series, he wrote, “Silvio García put on a base-running show. With Johnny Sullivan on second base, García doubled off the foot of second baseman Bob Young, scoring Sullivan, then took third when the bag was unprotected. On a wild throw from outfielder Dick Williams that went into the Almendares dugout, García continued home with the winning run. García was the hero the following afternoon in the opener of a twin bill, when with the score 6 to 4 in favor of Marianao, he drove a curveball from Sandy Consuegra over the wall for a three-run homer and a 7-6 Cienfuegos triumph.”11

García returned to Sherbrooke one last time in 1951, batting .346. However, he slipped significantly in the 1951-52 Cuban season, hitting only .232 for manager Billy Herman of Cienfuegos. However, he had one last notable achievement. While García may have missed out on the fame and glory that would have come his way by integrating Organized Baseball, he broke the color line in the Class-B Florida International League on April 9, 1952, when he and teammate Angel Scull took the field for the Havana Cubans against the Miami Beach Flamingos, who also had a black player on their roster, George Handy. While Havana finished at 76-77, García led the league in hitting at .283 and doubles with 22 while Scull led the league in numerous categories himself, including hits, runs, triples, and stolen bases.

García switched allegiances in the 1952-53 Cuban League season, joining his protégé Miñoso on the Marianao Tigres after 10 seasons with Cienfuegos. Sporting an infield of Lorenzo Cabrera at first, Ray Dandridge at second, García at shortstop and Don Zimmer at third base, and with Miñoso having an MVP season, the Tigres finished a strong second behind González’s Leones, who won their third consecutive championship in what would be their manager’s final season as field general.

By 1953 Branch Rickey had moved on from Brooklyn to the Pittsburgh Pirates, and had his team hold spring training in Havana, at Gran Stadium. The Pirates played a 10-game exhibition series against a team of Cuban players that included García, and won six of them. In the 1953-54 campaign, García was traded from Marianao to the eventual league champions, the Almendares club, but came to bat only 64 times, hitting .172. His career as a ballplayer in Cuba had come to an end, 19 years after it had begun.

While Rickey, for whatever reason, ultimately looked elsewhere for the player to enact his grand experiment, his decision should not lessen García’s reputation as a player. His pitching record in Cuba consisted of 36 starts, of which he completed 20, with a 13-12 record. On offense, he hit .282 in a career that spanned 23 years, many of those spent in difficult hitting environments. During his career in Mexico he hit .335/.386/.484, and stole 130 bases. In the only two seasons he played in the United States, he hit .318 and .333 in the Negro National League.

His fellow players were effusive with praise for García’s abilities. Adrian Zabala said of García, “Silvio García was one of the best pitchers in the professional league in Cuba. And he was one of the best shortstops in the league, too. He weighed about 200 pounds or more and he was a good runner and a good infielder and could throw the ball like a bullet.”12 Veteran major leaguer Julio Becquer said, “Oh God, I don’t even know who to compare him to. He was a big guy for a shortstop, 6-2 or 6-3, and he weighed around 200 or some pounds. He was so agile it was incredible.”13 Carl Erskine played with García in Cuba. “I remember him very well,” he said. “He was a handsome guy, big. He was big for what we think of shortstops, as willowy, loose and limber. He was a big man and had good power to right-center. I think his age might have been against him.”14

Followers of the game in Cuba respected García as well. Angel Torres, a Cuban sports journalist, wrote that in his opinion, García could have played with great success in the major leagues. Torres believed that there were only a handful of Cuban blacks who would have rated higher than García: Dihigo, Bragaña, Cristobal Torriente, Jose Mendez, Alejandro Oms, and perhaps a few others.15 Pedro Galiana, a sportswriter in Havana at the time, wrote of García, “The Cienfuegos shortstop is rated the most finished Cuban player and ranks second only to Conrado Marrero, the Almendares pitcher, in popularity.”16

Silvio García retired in 1954. After Fidel Castro’s rise to power, he returned to Cuba. Felix Delgado drove him to the airport, and during the trip García expressed his reservations about returning home. “Felix, I think I will only return here by boat because things are changing in my country. Things are not good,” he said.17 Delgado found out later that García had been denied exit from Cuba. He was not heard from again.

He was elected to the Salón de la Fama del Béisbol Latino in La Romana of the Dominican Republic in 2014.

Silvio García died on August 28, 1977, in Cuba at the age of 63.

This biography originally appeared in “Cuban Baseball Legends: Baseball’s Alternative Universe” (SABR, 2016), edited by Peter C. Bjarkman and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

Bjarkman, Peter. Diamonds around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005).

Echevarria, Robert Gonzalez. The Pride of Havana: A History of Cuban Baseball (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

Figueredo, Jorge S. Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003).

Minoso, Minnie, and Herb Fagen. Just Call Me Minnie: My Six Decades in Baseball (Urbana, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing, 1994).

Riley, James A. The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf, 1994).

Thanks to Virgilio Partida Bush for help with Mexican baseball statistics.

Notes

1 Jim Kreuz, “Jackie Robinson Wasn’t the Dodgers First Choice,” Presentation, Society for American Baseball Research National Convention, Houston, Texas, August 2, 2014.

2 Nick C. Wilson, Early Latino Ballplayers in the United States (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2005), 160.

3 Ibid.

4 Bill Nowlin and Jim Sandoval, Can He Play? A Look at Baseball Scouts and Their Profession (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 1994), 46.

5 Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007), 349.

6 Lyle Spatz, ed., The Team That Forever Changed Baseball and America (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012), 4.

7 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 56.

8 Milton Gross, “Speaking Out,” New York Post, January 29, 1954.

9 Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 145.

10 Brent Kelley, Voices From the Negro Leagues: Conversations With 52 Baseball Standouts of the Period 1924-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2005), 165.

11 Lou Hernandez, The Rise of the Latin American Baseball Leagues, 1947-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2011), 116.

12 Wilson, 161.

13 Ibid.

14 Nick Diunte, interview with Carl Erskine, posted August 28, 2011, at: http://examiner.com/article/carl-erskine-reveals-how-he-revolutionized-his-curveball-cuba.

15Peter Bjarkman, Baseball With a Latin Beat: A History of the Latin-American Game (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1994), 148-9.

16 Hernandez, 101.

17 Wilson, 162.

Full Name

Silvio Garcia Rendon

Born

October 11, 1914 at Limonar, Matanzas (CU)

Died

August 28, 1977 at , Matanzas (CU)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.