Skip Caray

“Braves Win! Braves Win! Braves Win! Braves Win! … Braves Win!!”

That call still gives fans of the Atlanta Braves goosebumps.1 That’s how Skip Caray ended his description of the play that sent the 1992 Braves to their second consecutive World Series. He repeated his signature “Braves Win!” line a few times more than usual after Sid Bream barely beat the throw to the plate (a play that will forever be known in Atlanta as “The Slide”), capping a three-run ninth-inning rally in the deciding seventh game of the NLCS.

Three years later, Caray made another memorable call when the Braves clinched their first (and thus far only) World Series championship. Many fans still use a “talking” bottle opener2 that allows them to savor that moment every time they open their favorite beverage:

… Fly ball deep left center, Grissom on the run… Yes! Yes! Yes! The Atlanta Braves have given you a championship! Listen to this crowd! A mob scene on the field!

Both calls reflect one of Caray’s trademarks as an announcer. He gave the details of the play and then turned his — and his audience’s — attention to the action on the field,3 saying “Listen to this crowd!” or “Just watch.”

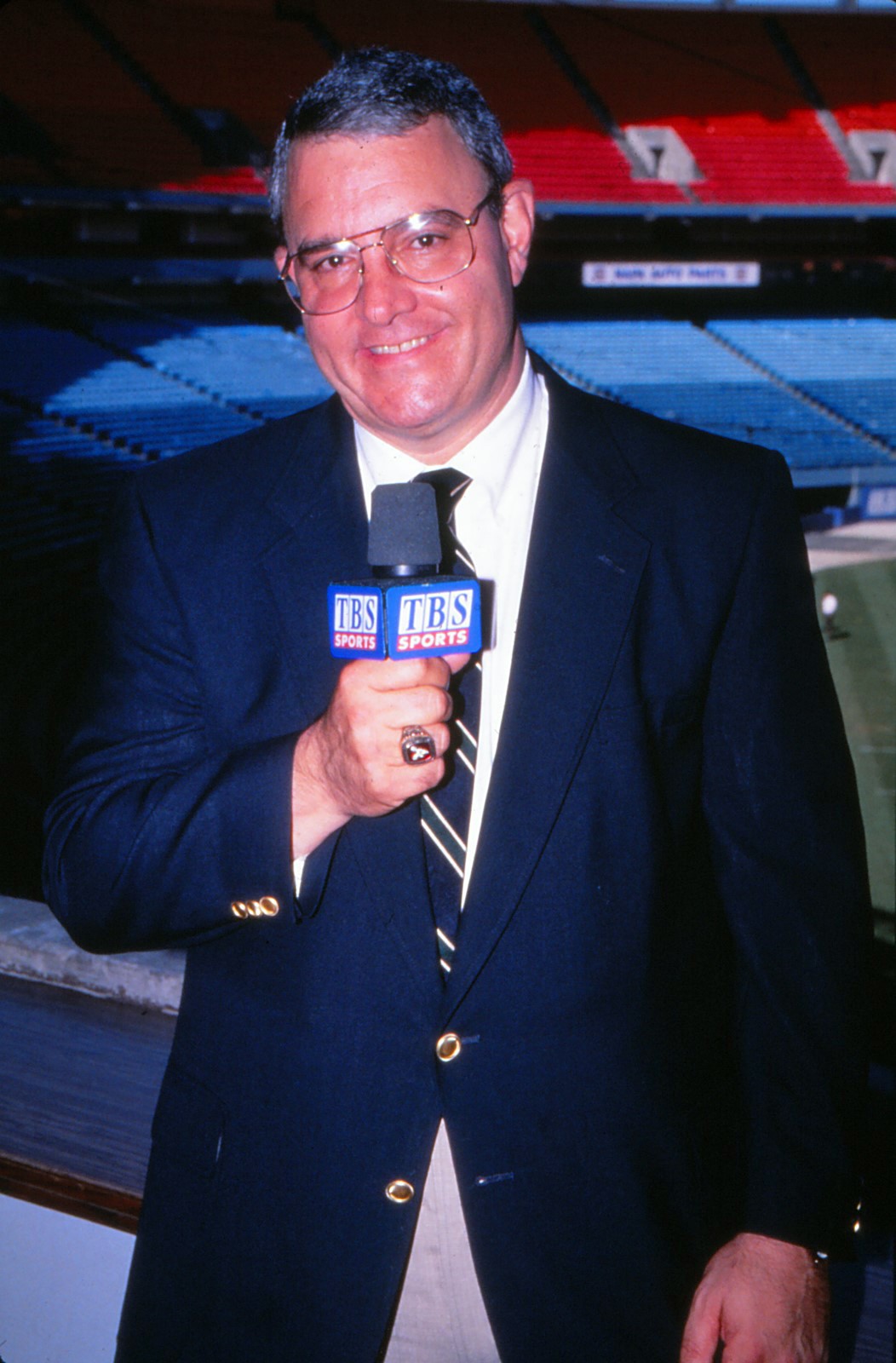

Those calls were two of the many that endeared Harry Christopher “Skip” Caray Jr. to most fans of the team that he (with a powerful boost from Superstation TBS) helped to make “America’s Team.” Caray spent the last 33 years of his distinguished broadcasting career as a member of the Atlanta Braves broadcast team. Perhaps it was inevitable that the son of the legendary Harry Caray would follow in his father’s footsteps, as his father hoped that he would.4 However, that career was not a foregone conclusion. He knew that having a famous father might open job opportunities he might not have gotten otherwise, but he also knew that his every action would be carefully scrutinized and therefore he would “have to be even better.”5 He later said, “I wanted to be judged on my own ability, my own style.”6

Those calls were two of the many that endeared Harry Christopher “Skip” Caray Jr. to most fans of the team that he (with a powerful boost from Superstation TBS) helped to make “America’s Team.” Caray spent the last 33 years of his distinguished broadcasting career as a member of the Atlanta Braves broadcast team. Perhaps it was inevitable that the son of the legendary Harry Caray would follow in his father’s footsteps, as his father hoped that he would.4 However, that career was not a foregone conclusion. He knew that having a famous father might open job opportunities he might not have gotten otherwise, but he also knew that his every action would be carefully scrutinized and therefore he would “have to be even better.”5 He later said, “I wanted to be judged on my own ability, my own style.”6

Skip Caray was born in St. Louis on August 12, 1939. His mother was Harry Caray’s first wife, Dorothy Kanz. When he was 7 years old, he learned that his parents were splitting up when, as he walked to school, he saw a newspaper headline saying “Caray’s Wife Tunes Him Out.”7 He didn’t live with his famous father after that, but they stayed close, and he was able to join him in Florida for part of spring training. Once the Cardinals’ season started, the young Caray often hung around the ballpark with his father during the early innings before heading home by bedtime.8 Every night at 8:30, the elder Caray would pause during his broadcast to say, “Goodnight, Skippy.”9 Years later, Skip said that he would never forgive his father for doing that because he was kidded about it all through high school — even by opposing football players.10

As a teenager Caray had no interest in broadcasting because “my dad had the corner on that.”11 He earned all-city recognition as a 6-foot, 220-pound linebacker12 on his high-school football team and aspired to be a professional football player until a knee injury quashed that dream.13 He also played baseball, but later recalled that his only pitch was a fastball and he was wild, resulting in an 0-2 record as a senior.14 While in high school, at age 15, he also started his broadcasting career with a once-a-week radio show during which he interviewed young athletes. Harry Caray, who later claimed to have devised a “master plan” to give his son that opportunity,15 publicly greeted news of that show with a paraphrase of his famous home-run call: “It might be, it could be, it is — another sports announcer coming to haunt me.”16

After high school Caray enrolled at the University of Missouri, where his journalism major kindled an interest in broadcasting.17 During the summers he worked at KMOX in St. Louis. He also wrote, produced, and directed a nightly sports show on campus and made his play-by-play debut at the state high-school basketball tournament. He also teamed with his father to broadcast the university’s football games18 and with Jack Buck to call Saint Louis University’s basketball games.19

Following graduation with honors from Missouri in 1961and a brief tour in the Army, Caray struck out on his own in 1963. He moved away from St. Louis to (at least partially) escape his father’s shadow and joined the broadcast team of the Tulsa (Oklahoma) Oilers, a farm team of the major-league Cardinals. The Sporting News speculated that it was “the first time that father and son have aired [baseball] games simultaneously.”20 In Tulsa the young Caray had to re-create play-by-play action for road games from the Western Union ticker tape that provided pitch-by-pitch updates. He struck a small piece of balsa wood to simulate the crack of a bat.21 In midseason he left the Oilers and became the Atlanta Crackers’ announcer, a job he held until the minor-league Crackers were displaced by the arrival of the Braves from Milwaukee in 1966.

On November 23, 1963, Caray and his father participated in an event that was believed to make radio history. KMOX offered the first-ever simultaneous radio broadcast of three college football games. Harry Caray did play-by-play for the Illinois-Michigan game while Skip handled Missouri’s game at Kansas, and Jack Buck covered Oklahoma at Nebraska.22 That same month, Caray married Lila Jean Osterkamp in a civil ceremony that was formally blessed in a church ceremony the following April.23

Two years later, Caray enjoyed two milestone events. In February Lila gave birth to their first child, Harry Christopher Caray III. They called him Chip, and he would grow up to join his grandfather and his father as a respected member of the sportscasting “fraternity.” Then on May 30, 1965, Skip broadcast his first major-league baseball game (Milwaukee Braves vs. Houston Astros in the Astrodome). That year, Atlanta’s WSB-TV was whetting the appetites of local fans for the Braves’ 1966 relocation by televising some of the Milwaukee games back to Atlanta. The legendary Mel Allen, one of the announcers for those telecasts, was not available for that May game because of a death in his family, and Caray was recruited to take his place. It was believed to be the first time the son of a major-league announcer broadcast major-league play-by-play.24

Caray joined the NBA Hawks as broadcaster for their final season (1967-68) in St. Louis. He then turned down an offer to become broadcaster for the NHL St. Louis Blues25 and moved to Atlanta to remain the “Voice of the Hawks.” By this time, a daughter (Cindy) had joined the Caray household, and — in an eerie echo of his own father’s behavior — Skip left his family on what Lila described to the children as “a long road trip”26 that ended with a divorce in 1970.

Caray soon became an Atlanta institution. Jesse Outlar, the Atlanta Constitution sports editor, celebrated the arrival of the “accurate and entertaining basketball announcer” who was “a “welcome addition to the local sports colony.”27 A few months later, Outlar praised Caray as a “personable and talented” announcer whose “knowledgeable broadcasts” had attracted a wide fan base for the Hawks.28 In 1970 Caray won his first Georgia Sportscaster of the Year Award, an honor that he received again in 1973 and 1974.29 When Harry Caray, by then broadcasting Chicago White Sox games, won the Illinois version of that award in 1974, the Carays had achieved another “father-son” first (recognition as their state’s top sportscaster in the same year).30

During those early years in Atlanta, Caray continued to build the Hawks’ radio fan base and gained experience covering a team that lost regularly in the postseason.31 In 1969, when the Hawks added television coverage, Caray moved to TV and turned the radio mic over to Larry Munson, who was well-known to local sports fans because of his play-by-play calls of University of Georgia Bulldogs football games. Caray later admitted that, to make that change, “I had to lie that I had done television before. I never had, but I was afraid it would cost me my job.”32 His on-the-job training obviously was successful.

By 1970 Caray was enough of a local “celebrity” to be featured in the advance billing of the annual July 4 “Salute to America” parade down Peachtree Street with Debbie Reynolds, several Atlanta Braves stars, and Peanuts’ Snoopy.33 Caray also hosted a regular weekday radio show and was a frequent emcee at functions hosted by the Hawks Booster Club and the Braves 400 Club, where his sarcastic wit soon earned him a reputation as “the South’s Don Rickles.”34 He also found time to support local charities, serving as Georgia Epilepsy chairman35 and co-hosting a Super Sports Telethon to benefit exceptional children.36

In 1971 a comment in the Atlanta Constitution that must have warmed Caray’s heart reported that the new broadcaster for the Chicago White Sox was Harry Caray and identified him as “the pop of Atlanta Hawks announcer Skip Caray.”37

In 1973 Caray did play-by-play of a hockey game for the only time in his career. He had to fill in on short notice for longtime friend and colleague Jiggs McDonald, who was the regular broadcaster for the NHL Atlanta Flames, and (as befits a legend) there are varying accounts of his performance. Furman Bisher said that “you never knew the difference except for the accent.”38 However, Bob Neal, who shared the broadcast booth that night, said that Caray did not know the players’ names and “just said ‘our guy’ or ‘the bad guys.’”39 McDonald himself said he listened to the game, and Caray used names for the visiting players. When McDonald asked where he got those names, Caray replied that he used the names of former college classmates.40

On June 17 of that same year, Caray and McDonald teamed up for a broadcasting first. They provided commentary for the tape-delayed telecast of a May 3 game between the Atlanta Apollos and the Montreal Olympics of the North American Soccer League. It was the “first indoor soccer game in a major arena”41 and yet another in the growing list of sports that Caray covered in his career.

In January 1976 Atlanta communications mogul Ted Turner, whose station WTCG (later to become WTBS) carried the telecasts of all of Atlanta’s pro sports teams, purchased the Atlanta Braves. Later that month, the Braves announced their new broadcast team. Caray, who had been with WTCG since it acquired broadcast rights to the Hawks’ games in 1972, and Pete Van Wieren were the new guys joining longtime Braves announcer Ernie Johnson. That announcement was only the beginning of what would be a watershed year for Skip Caray.

Caray shared the new team owner’s “irreverent distaste for stodgy rules”42 and believed that Turner meant it when he told him to say whatever he wanted. During those early days, when the Braves’ baseball was sometime boring. Caray would thumb through TV Guide and offer uncomplimentary reviews of whatever was coming up next on TBS.43 Later, Turner upbraided him for criticizing the team, but backed down when Caray pointed out that the Braves were in last place.44

Caray had turned down an opportunity to join his father on the Chicago White Sox broadcast team. He preferred to remain in his new hometown and to continue creating his own image. Although he may not have known it at the time, he had chosen the career path that he would follow for the rest of his life. In February 1976 he entered into another lifelong and life-changing relationship when he remarried. His new wife, Paula Prather, was a widow with an 8-year-old daughter (Shayelyn), whom he adopted.45 He and Paula were together for the rest of his life, and she became his “best friend.”46

In July Caray was awarded a new contract to continue as the Hawks’ play-by-play announcer with the added responsibilities as director of media sales for the Omni. Coliseum.47 On a much less serious note, a few days later (on July 26, 1976) he donned racing silks and joined the new Braves owner and others in a pregame ostrich race. Caray later claimed to have won the race despite having a “slow dumb ostrich,”48 but Bob Hope (not “Old Ski Nose”), the PR “brains” behind that race, said a local sportswriter won.49

In December 1976 WTCG became the nation’s first “superstation.” By 1982 the station (now WTBS) was bringing Braves baseball to more than 21 million subscribers.50 The voices they heard belonged to the Braves broadcasting trio, who had barely known each other when they stood together for their introductory announcement. They had soon developed an entertaining chemistry that endeared the lackluster51 Braves to a nationwide audience for 13 years — until Ernie Johnson decided to move exclusively to radio in 1989. According to Furman Bisher, while “sundry others came and went,” that trio “became engraved on the hearts of Braves’ listeners.”52

Each member of that trio also earned a place among the top 60 “all-time best announcers” based on the rating system developed by Curt Smith.53 Any such ranking is subjective and every one of these “mikemen” (except for number one Vin Scully) is sure to have admirers who think they should be rated higher. Smith tried to minimize disputes by ranking each announcer on a scale of 1-10 in each of 10 criteria, but those ratings are subjective and therefore open to disagreement. Atlanta fans might even disagree about Johnson (number 43) being rated higher than Caray (45) and Van Wieren (59). Regardless of how one feels about individual ratings, however, having all three men who shared broadcasts for one major-league team for 13 years appear on this list is unprecedented.

Before that first season together, Caray, who was to do television only, said that he was looking forward to doing baseball again and talked about the differences between broadcasting baseball and basketball. He noted that the slower pace of baseball gives a broadcaster “more time to do your job, which is basically to tell the people who’s winning, to educate them about the players, to keep the listeners and viewers in the game.”54 He also observed that working with others was going to be interesting for him because most of his basketball work was solo. Working as a team turned out pretty well; together “good ol’ Ernie and funny ol’ Skip and the learned Professor [Pete]” were, “in the grand scheme of things, as good as broadcasting ever got.”55 That trio dominated the Georgia Sportscaster of the Year award as one of them was honored in 10 of their 13 years together. Caray earned another four awards (1979-81-84-87) while Johnson (1977-83-86) and Van Wieren (1980-88-89) each claimed three.

During his first 16 years with the Braves, Caray continued as the Atlanta Hawks’ primary broadcaster, providing “superb play-by-play coverage … mixed with off-the-wall dry-witted insights.”56 He still found time to take on a few other assignments that further demonstrated his versatility as a play-by-play announcer, and he experienced some significant personal changes.

In 1982 Caray briefly negotiated with the Mets before signing a three-year contract with TBS,57 and he and Paula became the parents of yet another future sportscaster. Josh Caray would grow up to become the play-by-play announcer for college football and men’s basketball (Stony Brook University) and baseball (Yale) and minor league baseball (the Rome [Georgia] Braves, Hudson Valley Renegades and, starting in 2020, the Rocket City [Madison, Alabama] Trash Pandas). When Caray learned that his new son had asthma, he quit smoking “cold turkey,” even though he admitted that he had “smoked like a forest fire” until then.58

On December 11 of that same year, Caray was in the booth at the Capital Center in Landover, Maryland, to call the ballyhooed basketball matchup between the University of Virginia and Georgetown, featuring Ralph Sampson and Patrick Ewing.59

On July 4, 1985, Caray was in the broadcast booth for another memorable game. It received no special hype beforehand, but assumed legendary status — at least in Atlanta. The Mets were in town to start a four-game series, and there was a sellout crowd of 44,947. Rain pushed the game’s 7:40 scheduled start time back by 84 minutes and caused a 41-minute interruption in the third inning. The game then went 19 innings (before the Mets prevailed 16-13) and ended at 3:55 A.M. Almost 10,000 hearty souls stuck around for the promised Independence Day fireworks … and got them, starting at 4:01 A.M. Nearby residents thought that the Civil War had returned and the city was again under siege. Caray said, “It’s the latest I’ve ever stayed out doing something I wasn’t ashamed of.”60

In 1985 Caray made his first and only movie with a cameo role in The Slugger’s Wife, which Caray himself described as “one of the worst movies ever made.”61 His sole foray into the world of publishing came nine years later when he co-authored (with Don Farmer) Roomies: Tales from the World of TV News and Sports, which did not become a bestseller,

In 1986 Caray was part of the TNT broadcast team for the inaugural Goodwill Games in Moscow. He covered boxing (paired with Paul Hornung)62 and motoball, which Atlanta newspapers described variously as a demonstration sport and a novelty sport and as either polo or soccer on motorcycles. Caray admitted that he knew little about the sport63 and opined that he didn’t think he was expected to treat it “like the Second Coming.”64 He did know that the goalies were the only players not on a motorcycle and noted that they would be easy to spot because they would be the “ones with tread-marks all over them.”65 He also admitted that he didn’t know the names of any of the players, but could “make up whatever names I want.”66 Years later, Braves CEO Terry McGuirk said he was sure he heard Caray “mention several Russian czars playing that day.”67 Caray was back (to cover baseball) for the 1990 Goodwill Games; motoball did not return. However, it is unlikely that Caray’s coverage was the reason the event was dropped from all future Goodwill Games.

Ernie Johnson announced in March 1989 that he planned to retire at the end of the season.68 A few days later, Skip Caray announced that he had hired an agent and would “explore other possibilities” when his contract expired also at the end of the season.69 Negotiations with TBS continued during the season, and an agreement was reached shortly after Caray was hospitalized overnight in Los Angeles after suffering shortness of breath, chest pains, and an irregular heartbeat.70 He was released in time to broadcast a 2:00 P.M. game the next day.

The 1990 Braves finished in last place and were so inept that one LA sportswriter suggested that TBS might stand for “Those Braves Stink.”71 A year later the team surprised everyone by winning the National League pennant, and Skip Caray had a memorable year for personal as well as professional reasons. His oldest son, Chip, had followed him into the “family business” and had experienced much early success. Early in 1991, he joined the Braves broadcast team to work primarily on the radio with Ernie Johnson, but also to replace his father when the elder Caray was doing play-by-play for the NFL Atlanta Falcons. The two Carays were also scheduled to do some Braves games together. The first time that happened (on April 26, 1991), the elder Caray warned his son, “If you don’t do a good job, I’ll take away your allowance.”72

Less than a month later, that duo joined Harry Caray for a broadcasting first that may never be replicated. For the first time, three generations from one family broadcast the same major-league baseball game. The date was May 13, 1991, when the Braves visited Wrigley Field. After a press conference at Harry Caray’s restaurant, all three Carays did an opening on-field segment. Then Harry went to the WGN booth as usual to call the Cubs game while Skip and Chip (dubbed “A Chip off the Old Blocks” by The Sporting News73) went to TBS to do the same. They called the same game, but did not do so side-by-side in the same broadcast booth. At the time, Skip downplayed the hoopla, saying, “The game is the story. The Braves are the story. Not us.”74 Later, however, he called that game his “most memorable.”75

With much less hype, the trio had shared a booth once before — on November 28, 1989. The two younger Carays were doing play-by-play of an NBA game in Miami — Skip for TNT and Chip for the Sunshine Network — and Harry, who was in town for a college football game, dropped by their broadcast booth and made a brief “cameo” appearance.76

On August 26, 1991, with the surprising Braves only one game behind the Dodgers in the National League pennant race, Caray carried off a rare broadcasting feat when he “covered” two games simultaneously. He was doing play-by-play of the Expos-Braves game in Atlanta, and the Braves had rallied from a six-run deficit to take the lead. The Dodgers were in Chicago in a close game, which was airing on the press-box TV in Atlanta, Caray started relaying the play-by-play of that game as well as the Braves game.77

Caray’s work with Braves soon required enough of his time that he had to give up two other major broadcasting jobs. The 1991-92 basketball season was Caray’s last as the “Voice of the Hawks” — a role he had played since the team came to Atlanta 24 years earlier. Caray had also done Atlanta Falcons football games in 1990 and 1991, a commitment that caused him to miss 25 Braves games in August and September 1991, when the team surprisingly was in the pennant race. He was relieved of those duties in 1992.

The Braves’ 1991 “worst-to-first” season began a string of 14 consecutive postseason appearances and 14 first-place finishes in 15 years, missing only 1994, when the players strike cut the season short and canceled the postseason. Skip Caray and Pete Van Wieren (and Don Sutton, who joined the team in 1989) were there for that entire streak as the “aural chroniclers of one of the best baseball runs ever.”78

The combination of the Braves’ consistently good performance and the wide coverage provided by the superstation created a huge fan base for the team and its broadcasters, and Caray was always the “most colorful and conspicuous”79 member of that broadcast crew. He was “the one we thought we knew best … the funny one … the snarky one.”80 His “dry wit and humor” made the broadcasts “more fun” without taking away from the action.”81 While those who liked him called him “witty and honest,” some found him “sarcastic and opinionated.”82 He was known for his “humor and … wit … and zingers, and also there was nobody better at calling a big moment.”83 His distinctive “nasally voice” and witty (often tongue-in-cheek) delivery84 were easily recognizable. He was a self-described “wise-ass cynic,”85 who became for many fans “the sound of summer in the South.”86 Caray told listeners “what was happening and also what [he] thought of what was happening.”87 According to his longtime broadcast mate, he was “brash, cynical, impatient” and “possessed one of the quickest minds … of anyone I’ve ever been around.”88

About the importance of mental quickness, Caray once observed, “I’ve known people who are a lot smarter than me who couldn’t do broadcasting because they didn’t have the ability to see something and get it out in a short period of time. I guess that’s a natural ability that some people have.”89 Caray obviously had that innate ability. Immediately after his memorable Bream call, broadcast partner Joe Simpson congratulated him for his “great call,” and Caray’s response was. “What did I say? I have no idea what I said.”90

Caray also possessed a “mysterious way of knowing the home town of fans who caught foul balls in the stands”91 — a trademark that made gullible listeners wonder how he could possibly know that the lucky fan was “a young fella from Hahira, Georgia.” Another oft-repeated line came during lopsided losses; Caray would tell listeners: “It is OK, folks, to go and walk your dog now, if you promise to support our sponsors.”92 He loved to label small crowds “partial sellouts”93 and to comment during day games on the number of older men who had brought their twentyish granddaughters/nieces to the game.94

During the 1990s the Braves continued to win during the regular season and falter in the postseason except for the magical 1995 season. Joe Simpson joined the broadcast team in 1992, and that four-man crew worked together in various combinations as the “Voice of the Braves” until Sutton’s departure in 2006. Their tenure was not always smooth, however, as changes in team ownership and increased competition for viewers affected their roles and eventually left Caray feeling estranged.

After losing the World Series in 1991 and 1992 and the NLCS in 1993 and seeing the postseason canceled in 1994, the Braves (the “Team of the Nineties”) finally stopped being “bridesmaids”95 and won the World Series, and it was Skip Caray who captured the moment. After calling the final out (see above), he noted, “It’s over. The monkey is off the Braves’ back.”96 Turner Sports called its one-hour video highlighting that season “Braves Win … It All.” Appropriately, Caray and Van Wieren provided the voiceover.97

During spring training in 1996, while broadcasting a game involving Braves reserve infielders, Caray offered the kind of one-liner that made him famous. He commented that a possible double play could go [Ed] Giovanola to [Tony] Graffanino to [Aldo] Pecorilli, which made him “hungry for some pasta.”98

Caray was in the local newspapers regularly in 1996 primarily because of his pregame call-in show. He was frequently accused of being rude with most of the complaints appearing in “The Vent: Selective Invective,” the Atlanta Journal-Constitution’s column that published anonymous complaints. Caray admitted that he “might be abrupt, but never purposely rude.”99 While one venter suggested that Caray had been cured (“Vent-ilated”100), the complaints continued for the next few years.

In 1997 the Braves had a new ballpark (Turner Field, which had been built for the 1996 Olympics), and Caray and the other broadcasters got to handle interleague games for the first time during the regular season. Caray dubbed this innovation “a healthy thing” because “the fans wanted it,” but observed that when you looked at the lineups, “you felt like you were loaded or at spring training.”101

In 1998 TBS switched from being a superstation to basic cable and announced in February that it would carry fewer Braves games. Later TBS would also change the pairings of the four broadcasters, and Caray would work with Joe Simpson, doing half of each game on radio and half on TV. Before that happened, Caray received word that his father was in critical condition in California. Harry Caray died on February 18 with his son and other family members at his bedside.

That May, during his first trip to Wrigley Field after his father’s death, Skip Caray talked about the impact that death and how the response of fans at the funeral had affected him. He said that he had “lost his edge,” and hoped to have “more patience” and be “less caustic, less acerbic.”102 The following month, while Caray was recovering from a bruised spinal cord sustained when he fell off a treadmill, Pete Van Wieren filled in for him as host of the pregame show. Afterward, he said he now understood why Caray was sometimes “cranky” on the show.103

That pregame show continued to be controversial. In 1999 another local radio station started a competing show called The Zone, and used ads that mimicked Caray’s snarkiness. Then, in an extensive profile piece,104 a new, more mellow Skip Caray was introduced. He talked openly about his past and how he had changed. He admitted that while between marriages he had followed in his father’s “hard-living footsteps.” He chased women and drank heavily. After he remarried, he gave up the first and somewhat moderated the second. He still enjoyed “cocktails and dinner, cocktail and dinner, cocktail and dinner…”105 and had “heard more last calls than play balls”106 until finally swearing off alcohol on New Year’s Day 2000. Caray attributed his recent makeover to two factors: (1) the continuing criticism of his grouchy persona on the pregame show, where he did not suffer fools, especially those who asked questions that he had answered many times (e,g, slugging percentage and the infield fly rule) and (2) his health. He had said earlier that the concern shown by fans in Chicago during this father’s funeral had touched him and given him a new appreciation for his fan base. The “new” Caray was a surprise to many and some said it was too long coming. Bob Wessler, former executive VP for TBS, said that Caray was “the most difficult employee” he ever dealt with.107

During that wide-ranging interview, Caray also talked about his philosophy toward calling a game. He said, “I’m always thinking of a guy driving a tractor-trailer rig across the South. … He wants to stop, but he can’t; he has to keep going; I try to keep him awake and entertain him.”108

Caray and Van Wieren celebrated their 25th anniversary as Braves broadcasters in 2000, and Caray may unknowingly have laid the groundwork for a future member of their profession. On May 21 he needed a day off to attend son Josh’s high-school graduation and asked John Smoltz, who was recovering from elbow surgery, to fill in for him. Smoltz did the color commentary alongside each of the other Braves broadcasters, perhaps gaining experience that served him well when he entered broadcasting after his Hall of Fame playing career. On July 30 Caray and Van Wieren were honored in pregame ceremonies at Turner Field; they threw out the ceremonial first pitch and received Braves’ jerseys bearing their names and the number 25.

At the end of that season, Caray was paired with Joe Morgan on NBC doing the American League Division Series (Yankees vs. A’s). It was the first time he had called a major-league game for other than TBS, and initially he showed a few jitters.109

In 2001 the Braves announced that all four members of the Braves broadcast team (later dubbed the Gab Four110) would take turns hosting the pregame show. There was no reference to earlier criticisms of Caray’s handling of this show. A year later, a body scan revealed that Caray had clogged arteries, and he underwent successful angioplasty. Shortly afterward, he was “honored” with his own bobblehead, about which he said, “It doesn’t look like me at all.”111

The success of TBS and other superstations had led to “explosive growth” of regional sports networks, and the Braves were no longer “the only game in town.”112 Things came to a head before the 2003 season. Executives at Entertainment Networks, the multimedia Times-Warner corporation of which TBS was now a part, decided to combat declining cable ratings by aiming for a broader audience. Its telecasts were renamed “MLB on TBS” rather than “Braves on TBS,” although the Braves would still appear in all of the games.113 Key to this re-imaging was the decision to have Don Sutton and Joe Simpson handle the nationally televised games on TBS and to relegate Caray and Van Wieren (who were considered “too biased” toward the Braves114) to radio and regional telecasts on Turner South. Local sportswriters and fans were shocked and quickly voiced their disapproval of the move. A nonscientific ajc.com/sports poll that asked, “Do you like the Braves juggling their TV announcers?” attracted 11,147 votes, 89 percent of which declared the decision to be “horrible.”115

Despite the negative reaction, the change was made, and TBS ratings dropped another 25 percent. While the executives offered other possible reasons for that decline, they soon reversed that decision and returned to the four-man setup after the All-Star break, using a new “mix and match” approach that kept the same pairs on radio and TV for the entire game. The change, which was attributed to “long and loud protests,”116 was front-page news in Atlanta. Upon his return, the usually crusty Caray was “downright syrupy”117 as he said that the public support was “humbling.”118 Perhaps he remembered saying after his first season with the Braves, “My job is really in the hands of the fans. If they like me, I work. If they don’t, I don’t.”119

A year after that temporary demotion, Caray and Van Wieren were jointly inducted into the Atlanta Braves Hall of Fame, joining longtime partner Ernie Johnson (Class of 2001). During that induction ceremony, Johnson talked of a surprising (to some) side to Caray, saying that he had “a bigger heart than anyone can imagine.”120 Caray was a longtime supporter of Camp Twin Lakes, for children with special needs; he adopted numerous rescue dogs and brought one into the broadcast booth on a “Bark in the Park” Day; he kept in touch with and visited a former Braves player who was in prison in Alabama.

Now that the fans had spoken, Caray and Van Wieren continued to be key members of the Braves broadcast team along with Sutton and Simpson. Chip Caray joined the team in 2005, after a successful lobbying effort by his father,121 giving the Braves five broadcasters. The Braves’ loss to Houston in the NLDS ended the team’s postseason streak, and more changes were coming. Early in 2006 Time Warner sold Turner South to Fox Cable Networks, and Fox replaced the TBS broadcast crew with its own people.122 The Braves also were for sale; Time Warner and Liberty Mutual completed that deal in May 2007.

Skip Caray’s heart issues that had surfaced in 1989 did not go away. In 2003, a year after his angioplasty, he received a Pacemaker. Although he had eventually given up cigarettes and alcohol, his high-school weight (210 pounds) had fluctuated in his later years between 230 and 290 pounds while his 6-foot height didn’t increase.123 Early in his career, his weight was often a source of humor, as when he quipped, “The opera isn’t over until the fat announcer shuts up.”124 It had become a source of concern. He was suffering from diabetes, congestive heart failure, arrythmia, and reduced kidney and liver function.125

Caray rode an emotional roller-coaster in 2007. He started the baseball season with a reduced role, relegated primarily to radio. On April 29 he drove 70 miles to Rome, Georgia, where he shared the broadcast duties with his youngest son, Josh, who was the regular announcer for the Braves’ Class-A farm team there.126 Later that season, TBS announced that it was parting ways with the Braves at the end of the season. In September he was hospitalized and missed several games, but returned to do play-by-play for the final Braves game on TBS on September 30. His partner for that game was his other son, Chip. He summed up that experience saying, “I did the first one and now I’ll be doing the last one. The only difference is I’ll be doing it with my boy. … Working with Chip on that last one will be an emotional day, but it’ll be great.”127 It was the end of an era, and it ended with a thud as TBS snubbed Skip (and Pete) when choosing its playoff broadcasters — a decision that Caray described as “hurtful” — especially because “nobody gave me a reason.”128 In October, he was in intensive care for three weeks, so close to death that his next of kin were told to stay nearby.129

Yet he was back for the 2008 season — for home games, at least — skipping spring training for the first time in his Braves career and accepting a reduced workload on Peachtree TV, the new home of the Braves. He missed a few games because of health issues, and at times “his delivery was a little slower and his speech a little slurry,”130 but most of the time he seemed to be his old self. On July 31 Caray had one “one of his best broadcasts of the year” as the Braves got their only win in a four-game series against the Cardinals. He was “sharp, alert, quick, funny, opinionated.”131 In short, he was like the Skip Caray of old. It was to be his last broadcast; his trademark signoff line (“So long, everybody.”) was never more appropriate.

Everyone was surprised that, after that performance, Caray was not able to come back the next night for the start of a three-game series against Milwaukee. He missed all three of those games, and the Braves left for the West Coast. During their flight — on August 3, 2008 — the team got the word that Skip Caray had died. Paula. his wife of 32 years, had found his body in the back yard of their home where he apparently was refilling the bird feeder.132 Despite his recent health issues, everyone who knew Caray was shocked by his death, which was front-page news in Atlanta under the headline: “Braves Lose the Voice That Made Us All Fans.”133

Tributes appeared in newspapers around the country, and fans throughout America shared their memories. One of those fans was former President Jimmy Carter, who said that he “enjoyed … [Caray’s] superb commentary on the games.”134 Braves President John Schuerholz declared, “Our baseball community has lost a legend today.”135 Furman Bisher suggested one last “Memorial Wave”136 for Caray, who had been a vocal and “ardent anti-wave activist.”137

On August 11, 2008, a huge crowd gathered early at Atlanta’s Cathedral of Christ the King “for a two-hour funeral Mass disguised as a celebrity roast.”138 It seemed fitting to many that the service started late because the Braves team bus was delayed by a traffic jam;139 during his broadcasts, Caray often gave “traffic reports” that belittled Atlanta’s seemingly never-ending road work. Once it began, the service was befitting a man with Caray’s sense of humor. In that ornate gothic edifice, Caray’s closest friends and colleagues remembered him — and regaled the mourners — with stories and remarks that, like Caray himself, were “honest and funny.” Even Monsignor Tom Kenny’s homily compared Caray’s spiritual journey “home” to a play at the plate and paraphrased a familiar call, intoning “Here comes the slide. … Skip’s safe. Listen to the crowd of angels and saints. They’re going berserk.”140

The day after the funeral, the Braves had a public tribute at Turner Field, where Georgia’s governor, Atlanta’s mayor, Braves executives, and fellow broadcasters shared their memories of Skip Caray. Commissioner Bud Selig sent a letter that called Caray “one of the great broadcasters of our era.”141 After that evening’s scheduled pregame salute was rained out, it was held the next night before the second game of day/night doubleheader. The band played “Amazing Grace”; highlights of his 33-year career with the Braves were shown on the center-field video board; and the Atlanta Police Department Honor Guard provided a 21-gun salute. The sign indicating that the main television booth was now the “Skip Caray Broadcast Booth” was unveiled, and the crowd responded with a standing ovation. Six of Caray’s seven grandchildren threw the ceremonial first pitch, and the Braves revealed the “SKIP” patch that they would wear on their right uniform sleeves for the rest of the season.142 Then the Braves were battered by the Cubs just as they had been in the first game, leading Bobby Cox to suggest that “Skip had a better night than the Braves did — much better.”143

On the first anniversary of Caray’s passing, Chipper Jones, who inspired one of Caray’s hallmark calls (“a chopper to Chipper), said, “Skip will not be forgotten. He was as much an icon in Atlanta as any ballplayer who ever came through here.”144 Caray continued to be honored after his death. In 2009 he and the recently retired Van Wieren received the Atlanta Sports Council’s first Furman Bisher Award for Sports Media Excellence.145

He was inducted into the Atlanta Sports Hall of Fame later that year and into the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame in 2013, but as of 2020 he had not received the honor that he most wanted. He has not joined his father as a recipient of the Ford C. Frick Award, which is presented to one sportscaster each year by the National Baseball Hall of Fame. The recipient is recognized during the Hall’s annual Induction Weekend, but is not an inductee, and therefore technically is not a Hall of Famer. The selection process has changed over the years, and for a few years a fan vote via Facebook chose three of the 10 candidates from whom the selection committee chose the winner. That was the case in 2008, and an article on the newspaper page describing Caray’s funeral encouraged fans to vote for him. Although he did not get enough votes to earn a spot on that ballot, Caray was on the 10-man ballot for the 2010 and 2012 awards. The selection committee chose another candidate in each of those years.

It would have been fitting for him to win the 2020 award on the 25th anniversary of the Braves’ World Series championship, but he was not even among the finalists for that year’s award. The fan vote has now been eliminated, but the website (inductskipcaray.com) that Paula Caray started after her husband’s death is still online and has several videos of Skip in action.

After his health scare in 2007, Caray said, “Without baseball, there would be a big hole in my life.”146 The converse is true: Without Skip Caray, there is a hole in baseball for fans who knew him as the “Voice of the Braves.” His voice is now silent, but the echo remains.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Historic Newspaper Archives (newspapers.com), the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s Giamatti Research Center, Paper of Record, and the Sports Illustrated Vault. He also watched numerous YouTube videos that allowed him to hear Skip Caray and experience once again small doses of his many talents.

Notes

1 Walter Bergeson, “5 Greatest Calls by Atlanta Braves Broadcaster Skip Caray,” Rant Sports (https://rantsports.com/mlb/2014/04/25/5-greatest-calls-by-atlanta-braves-broadcaster-skip-caray/).

2 The bottle opener may be available on eBay (ebay.com). The author used this often while researching and writing this article. Search on “Skip Caray Talking Bottle Opener.”

3 Bottle opener.

4 Harry Caray with Bob Verdi, Holy Cow! (New York: Villard Books, 1989), 212.

5 Tony Silvia, Fathers and Sons in Baseball Broadcasting (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2009), 93.

6 Tim Tucker, “Braves Lose the Voice That Made Us All Fans,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 4, 2008: A-4.

7 Tim Tucker, “Braves Lose the Voice That Made Us All Fans”: 92.

8 Caray, 211.

9 Larry Stewart, “Despite Caray-Over, Skip Calls the Game in His Own Glib Way,” Los Angeles Times, July 29, 1988. (Note: Some sources report that Harry Caray said, “Good Night, Skip.”)

10 Stewart.

11 “Skip Caray Has Made It on His Own,” Los Angeles Times, February 23, 1986. https://latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1986-02-23-sp-11097-story.html.

12 Ken Picking, “Skip Caray: Father Did Know Best,” Atlanta Constitution, December 22, 1979: 4-C.

13 “’93 Broadcasters,” Atlanta Braves FAN Magazine (Volume 28, Number 1): 60.

14 Bob Wolf, “Carays Set a Big-Time First,” The Sporting News, June 12, 1965: 27.

15 Picking: 1C; Caray, 212-214.

16 “Tuning In,” The Sporting News, July 11, 1956: 50.

17 Los Angeles Times, February 23, 1986: Archives.

18 Wolf.

19 Los Angeles Times, February 23, 1986: Archives.

20 Wolf.

21 Jack Wilkinson, The Game of My Life (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, LLC, 2007), 106.

22 “KMOX Airs Triple-Header: 3 Grid Games at Same Time,” The Sporting News, November 30, 1963: 32.

23 “Church Ceremonies Bless Marriage of Skip Caray,” The Sporting News, April 18, 1964: 59.

24 Curt Smith, Voices of the Game (South Bend, Indiana: Diamond Communications, Inc., 1987), 481.

25 Picking: 4C.

26 James Joyner, “Fathers Day for the Carays — A Special Day at the Park,” Outside the Beltway, June 19, 2005. outsidethebeltway.com/fathers_day_for_the_carays_-_a_special_day_at_the_park.

27 Jesse Outlar, “This and That,” Atlanta Constitution, November 8, 1968: 2-C.

28 Outlar, “This and That.” Atlanta Constitution, March 2, 1969: 2-C.

29 nationalsportsmedia.org/awards/state-awards/georgia.

30 Al Thomy, “On the Town,” Atlanta Constitution, April 24, 1975: 2-E.

31 From 1963 to 1968, the St. Louis Hawks lost six consecutive division finals or semifinals. After moving to Atlanta, the team continued that pattern, losing in the conference finals or semifinals for five years in a row (1969-1973).

32 Picking: 4-C.

33 Ad in Atlanta Constitution, June 26, 1970: 19-A.

34 George Cunningham, “Thurmond: Davis Is a Hustler,” Atlanta Constitution, October 24, 1969: 7-D.

35 “Caray Heads Charity Drive,” Atlanta Constitution, June 2, 1970: 3-C.

36 “Telethon Aids Kids,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution, May 21. 1972: 14-D.

37 Wayne Minshew, “Baseball Banter,” Atlanta Constitution, January 20, 1971: 5-D.

38 Furman Bisher, “Born to Broadcast,” Atlanta Constitution, August 5, 2008: D-7.

39 “Fans and Colleagues React,” Atlanta Constitution. August 5, 2008: D-7.

40 Carroll Rogers, “Wit, Calls of Caray Celebrated,” Atlanta Constitution, August 12, 2008: D-4.

41 “Heavy Rains Stop Apollos,” Atlanta Constitution, May 3, 1973: 2-D.

42 Eldon L. Ham, Broadcasting Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: MacFarland and Co., 2011), 193.

43 Jim Cofer, “R.I.P. Skip Caray,” (jimcofer.com), August 4, 2008.

44 Tucker, “Braves Lose the Voice That Made Us All Fans,” 92.

45 Stewart.

46 Picking: 4-C.

47 “Caray Gets a New Deal with Hawks,” Atlanta Constitution, July 25, 1976: 4-D.

48 Wilkinson, 106.

49 Bob Hope, We Could’ve Finished Last Without You, quoted in “Q&A on the News,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, October 31, 1995: A-2.

50 Curt Smith, Voices of the Game, 444.

51 Only three winning seasons in 14 years (1976-1989).

52 Furman Bisher, “Born to Broadcast,” Atlanta Constitution, August 5, 2008: D-1.

53 Curt Smith, Voices of Summer (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2005), 392, 248-252, 348-352, 352-354.

54 Darrell Simmons, “Three on a Mike: Broadcast Team Varies in Style,” Atlanta Constitution, April 9. 1976: 7-S.

55 Mark Bradley, “2nd Lifelong Voice of Braves Retires,” Atlanta Constitution, October 22, 2008: D-4.

56 “TV Week,” Atlanta Constitution, February 15, 1981: 2. (Caray is pictured on the cover.)

57 Tim Tucker, “Braves Acquire Journeyman Moore,” The Sporting News, February 20, 1982: 42.

58 Furman Bisher, “Caray Versatile and Direct,” Atlanta Constitution, August 5, 2008: D-4.

59 That game is available in its entirety on YouTube; UVA won 68-63. youtube.com/watch?v=RGiTVTaGq90.

60 Guy Curtright, “Camp’s Longest Hit Lives,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 4, 1999: D-2.

61 alchetron.com/Skip-Caray.

62 Rosen, “Caray Claims Unique Goodwill ‘Duties,’” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 21, 1986: D-8.

63 Rosen.

64 John Carman, “Can Skip Carry His Weight in Coverage of Motoball?” Atlanta Constitution, July 11, 1976: C-1.

65 Carman.

66 Carman.

67 “Caray Tribute,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 13, 2008: D-8.

68 Prentis Rogers, “Ernie Johnson Will Retire After Season,” Atlanta Constitution, March 3, 1989: F-1.

69 Rogers, “Inside TV-Radio Sports,” Atlanta Constitution, March 7, 1989: D-2.

70 Joe Strauss, “Caray Hospitalized, Released Later,” Atlanta Constitution, September 16, 1989.

71 Mike Downey, “TBS: Is It Short for Those Braves Stink?” Los Angeles Times, April 11, 1990.

72 Glenn Sheeley “Sports Scene,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, April 27, 1991: C-2.

73 Leslie Gibson, “A Chip Off the Old Blocks,” The Sporting News, May 13, 1991: 55.

74 I.J. Rosenberg and Prentis Rogers, “Harry, Skip, and Chip Get to Caray on Together,” Atlanta Constitution, May 14, 1991: E-1.

75 Wilkinson, 106.

76 Jeff Schultz, “A Caray Collision,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, May 13, 1991: E-6.

77 Jeff Schultz, “On the Air,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 27, 1991: F-6.

78 Bradley, “2nd Lifelong Voice of Braves Retires.”

79 Curt Smith, Voices of the Game, 480

80 Mark Bradley, “Caray Called with Humor and Honesty,” Atlanta Constitution, August 4, 2008: D-1.

81 “Braves Broadcasts,” FAN, 1982 (Atlanta Braves Official Scorebook/Vol. 17, No. 4): 35.

82 Tyler Barnes, “Telling It Like It Is,” Braves Illustrated: Official 1988 Yearbook: 55.

83 Kirk McKnight, The Voices of Baseball (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), 288.

84 Tucker, “Braves Lose the Voice That Made Us All Fans.”

85 Tucker, “Braves Lose the Voice That Made Us All Fans.”

86 Tucker, “Braves Lose the Voice That Made Us All Fans.”

87 Bradley, “Caray Called with Humor and Honesty.”

88 Pete Van Wieren with Jack Wilkinson, Of Mikes and Men (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2010), 151.

89 Martha Payne, “Family Business,” FAN ’98 (Braves Magazine and Scorecard: Vol. 33, Issue 2): 66.

90 Atlanta Journal-Constitution, “Caray Tribute,” August 13, 2008: D-8.

91 Mike King, “Skip, TBS Helped Make Atlanta,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, October 2, 2007: A-10.

92 ecelebritymirror.com/celebrity-babies/skip-caray-harry-carays-son-dorothy-kanz/.

93 Bob McCoy, “Keeping Score,” The Sporting News, December 10, 1984: 8. (19,548 capacity; 3,605 attendance).

94 Cofer.

95 Van Wieren, 133.

96 “Braves Broadcaster Skip Caray’s Call of the Final Out,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, October 30, 1995: C-19.

97 Prentis Rogers, “TV-Radio,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, December 16, 1995: E-2.

98 I.J. Rosenberg, “Braves Notebook,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 24, 1996: E-4.

99 “Peach Buzz,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution August 29, 1996: G-2.

100 “The Vent,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution September 3, 1996.

101 Rogers, “TV/Radio,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 13, 1997: D-2.

102 Wilkinson, “Tough Wrigley Visit for Skip,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, May 31, 1998: D-1, D-7.

103 Rogers, “Radio-TV,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 14, 1998: D-2.

104 Drew Jubera, “A Less Harried Caray,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, May 21, 2000: M1, M-3.

105 Christian Boone, “Wit, Calls of Caray Celebrated,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 12, 2008: D-4.

106 Glenn Sheeley, “Caray Announcers’ Youngest Member Isn’t Totally a ‘Chip Off the old Block,’” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, June 8, 1991: D-2.

107 Jubera: M-3.

108 Jubera: M-3.

109 Rogers, “Radio/TV,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, September 8, 2000: G-2.

110 Mike Tierney, “Braves Rehire Broadcasters,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, November 13, 2002: C-1.

111 Wilkinson, “Doll Has Caray Shaking His Head,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 20, 2002.

112 Van Wieren, 160.

113 Tucker, “‘Too Braves’ for TBS,” Atlanta Constitution, March 27, 2003: E-1.

114 Van Wieren, 160.

115 Atlanta Constitution, March 27, 2003: E-1.

116 Tucker, “Skip and Pete Back on Braves Telecasts,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, July 8, 2003: A-1.

117 Steve Hummer, “Free Range,” Atlanta Constitution, July 19, 2003: C-2.

118 Tucker, “Skip and Pete Back on Braves Telecasts.”

119 Darrell Simmons, “Caray Not a ‘House’ Man,” Atlanta Constitution, October 23, 1976: C-2.

120 Tucker, “Braves Lose the Voice That Made Us All Fans.”

121 Van Wieren, 171.

122 Tucker, “Turner South Crew Replaced,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, April 29, 2006: D-1.

123 Picking.

124 Picking.

125 Carroll Rogers, “Ailing Caray Will Skip Road,” Atlanta Constitution, April 1, 2008: D-2.

126 Tucker, “This Is Something I Was Born to Do…,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, May 5, 2007: A-1, A-10.

127 Rogers, “Skip Caray Back in Booth,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, September 20, 2007: D-5.

128 Tucker, “‘Hurt’ Caray Off Post-Season Team,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, September 27, 2007: D-1.

129 Rogers, “Ailing Caray Will Skip Road.”

130 Van Wieren, 185.

131 Van Wieren, 185.

132 Tim Tucker, “Wife, Family Coping with Death,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 5, 2008: D-1.

133 Tucker, “Braves Lose the Voice That Made Us All Fans.”

134 “Fans and Colleagues React,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 5, 2008: D-7.

135 “Braves Announcer Skip Caray Dies,” Sports Illustrated, si.com/mlb/2008/08/04/skip-carayobit.

136 Furman Bisher, “Caray Versatile, Direct,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 5, 2008: D-4.

137 Jack Wilkinson, “The Men in the Booth,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 7, 1991: E-1.

138 Terence Moore, “The Stories and Jokes of His Life Remembered, “Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 12, 2008: D-1

139 “Only Fitting,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 12, 2008: D-4.

140 Rogers, “Even the Monsignor Borrows Famous Line,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 12, 2008: D-1.

141 “Caray Tribute,” Atlanta Constitution, “August 13, 2008: D-8.

142 David O’Brien, “Braves Report,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 14, 2008: C-3.

143 O’Brien, “Double the Trouble,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 14, 2008: C-3.

144 O’Brien, “Skip Caray Still Intensely Missed,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 4, 2009: C-2.

145 Furman Bisher, “My Opinion,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, January 25, 2009: C-2.

146 Rogers, Atlanta Journal-Constitution, September 20, 2007.

Full Name

Harry Christopher Caray

Born

August 12, 1939 at St. Louis, MO (US)

Died

August 3, 2008 at Atlanta, GA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.