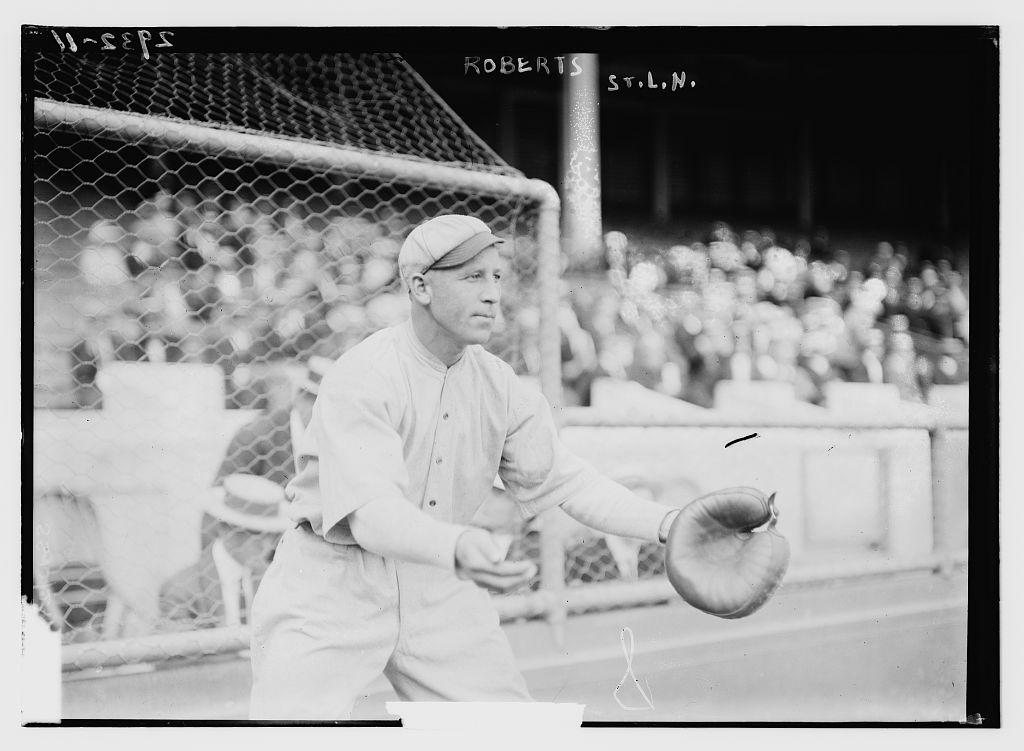

Skipper Roberts

Skipper Roberts became the third man born in the state of Idaho to make the big leagues when he appeared in 26 games with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1913. The catcher suited up for 56 Federal League games the following summer with the Pittsburgh Rebels and Chicago Feds before a barroom fistfight finished his big-league career. After he blackened both eyes of his Hall of Fame minor-league manager in 1916, his playing days were done for good.

Skipper Roberts became the third man born in the state of Idaho to make the big leagues when he appeared in 26 games with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1913. The catcher suited up for 56 Federal League games the following summer with the Pittsburgh Rebels and Chicago Feds before a barroom fistfight finished his big-league career. After he blackened both eyes of his Hall of Fame minor-league manager in 1916, his playing days were done for good.

Clarence Ashley Roberts, born January 11, 1888 in the mining camp of Wardner, Idaho, was the third of four boys born to surveyor/contractor Joshua T. and his wife, Rosaltha A. (Sylvester) Roberts. Clarence’s brothers were named Harry T., Franklin S., and Thornton A. Before following the mining boom to the Silver Valley of Idaho, the family of English and Welsh heritage called Leadville, Colorado, home. The Roberts were living in Washington state no later than 1895. Every reference to Clarence’s hometown is that of Spokane, leading the author to believe the boys played their first ball games in the Evergreen State.

Before his days on the diamond, Roberts served as a 3rd class gunner’s mate in the US Navy from 1902-1906.1 Sailor Roberts, as he was known in his early professional days, made his first mention in the sporting papers in June of 1908 playing in the Northwestern League for his hometown Spokane Indians.2

Roberts, “signed from the City League,” got his chance after the regular catcher split his hand between the first two fingers. He “secured a corking single after two strikes were on him” in his first game.3 Roberts wasn’t in the lineup two days later when the Indians faced 1903 World Series vet Gus Thompson and the Aberdeen Black Cats, but still garnered mention for his recent play.4

In early July, Roberts was on the bench when teammate Ed ‘Kickapoo’ Kippert lost his grip on the bat upon lifting a soft fly ball. The bat careened into foul territory and connected with Roberts’s forehead, causing the catcher to do a “record sprint to the clubhouse after a bandage.” An inning later, Roberts emerged with a smile and caught the rest of the game.5 The papers noted the 20-year-old “catches courageously,” but lacked experience in just his first professional season. By the end of summer they were singing a different tune after “Sailor Roberts caught a clever game.”6

Roberts also saw some playing time in right field, robbing “a home run by pulling down a long fly that was perilously near scraping the top boards of the fence.”7 When Roberts wasn’t receiving pitches from the likes of Jack Hickey, Jack Killilay, and Gene “Rasty” Wright, he found time to do some umpiring in the semipro Coeur d’Alene league. One such occasion was a ladies day game between Mullan and Wallace, hyped in the paper thus: “Ladies, if your fellow can’t come, come by yourselves.”8

Roberts recorded just 16 hits in 98 at-bats with Spokane, but showed enough potential to be the second player signed by Jack Holland for his 1909 Wichita Jobbers (Western League). The papers relaying, “He is a native of Spokane and wanted to get away from his home town.” George Ferris recommended Roberts to Holland.9

Getting the young recruit the 1,600 miles from Spokane cost Wichita a pretty penny in “railroad tickets, sleeper tickets, and meal tickets,”10 but could’ve cost Roberts a lot more as “according to the Sioux City Journal, Sailor Roberts, Wichita first basemen and catcher, had an experience on the train he will not soon forget, when he was mixed up unwittingly in a domestic entanglement.”11

Used primarily as a backup to Art Weaver in Wichita, Sailor Roberts was traded midseason to the McPherson Merry Macks of the Kansas State League.12 While with McPherson, Roberts hit his first documented home run over the left-field fence in the sixth inning of a 6-3 win over Wellington.13 Between the two mid-western squads Roberts got into 65 games and posted a .180 batting average. By September, Roberts was back in Washington, catching for Tacoma before Cliff Blankenship relieved him of duties with the Tigers.14

Possibly discouraged by his inability to stick with a pro club, or potentially unsigned because of his inability to stick the baseball, there is no mention of Roberts playing ball in 1910. The 1910 census has the family living in Spokane at 2205 Mallon Avenue, and Clarence listed as a bridge engineer. Roberts most likely was back playing in the city leagues of Spokane as he signed with Helena (Montana) of the Union Association in early April of 1911. Helena had a young Del Baker, so Roberts was shuffled to the Missoula Scrappers.15

The 1911 and 1912 seasons with Missoula were the only years that Roberts played in more than 65 games. His batting average raised nearly 100 points to .269 and .271, as Roberts, now known as Skipper, feasted on Class-D pitching. The evolution of Clarence’s nickname from Sailor to Skipper was probably due to Roberts’s being afflicted with a stutter, which his teammates in Missoula amused themselves with.16 Out of the gates in 1911, Skipper was near the tops of the circuit with a .419 average.17 An undisclosed midseason injury slowed his roll, and resulted in a much-publicized slump. Roberts “couldn’t get a hit to save his life,” teammate Harry Thompson said. “I don’t know what’s the matter with Roberts. He stands up there nice; he looks ’em over nice; he swings at ’em nice. Good Lord! He must be blind!”18 Roberts still made one of the league’s end-of-the-season all-star teams at first base.19 The paper praised him as a “Patient hitter and good bunter. He is very fast and runs the bases intelligently. And can slide with the best of them.”20

Skipper set sail for Spokane once winter rolled in, but reported to Missoula’s new manager, Cliff Blankenship, in early March. Biding his time before the bell rang for spring workouts, “Skipper Roberts, first basement of last season’s Missoula team and former 150-pound amateur champion of the northwest, was secured to referee boxing events.”21 It is unknown if Roberts learned to box during his stint with the Navy, or in the clubs or streets of Spokane, but his scrappy tendency seemed to have been backed up with ability. Said to be in the best shape of his life at spring camp in 1912, “The bugs had their eyes on Skipper Roberts, an idol of last season’s club.”22 The 5-foot-10, 150 pound lefty’s first at-bat of the season resulted in a slow roller to short that he beat out for an infield hit.23

The Garden City Brewing Company of Missoula were a big sponsor of the ball club. The brewery’s best known beer, Highlander, seemed a natural name for the team. After team owners wrote the New York team of the same name (soon to be christened the Yankees) requesting permission, the Missoula Highlanders were born.

At the mile-high mining camp of Butte in early May, the Highlanders and Miners played a pair in the rain and snow of “the fur coat league.” The weather didn’t seem to bother Roberts as he collected two hits including a two-RBI triple in the first game, then tripled and scored twice the following day.24 On May 21, with Missoula boasting a record of 21-4, Roberts dislocated his thumb.25 While he sat nursing his hand, Skipper did a lot of what the paper called, “strenuous coaching.”26

Undeterred by injury, when Roberts returned he experimented with working behind the plate without shin guards, believing they slowed him down.27 Strenuous coaching may have been another way to say hollering, as Roberts had a reputation for voicing his displeasure. At the end of June both Art Weaver and Roberts were fined $5 by Roberts’s former teammate in Spokane, “Rasty” Wright.28 A newspaper story two days later read, “Skipper Roberts is improving in his crabbing business. He expressed his disapproval only a few times yesterday.”29

After manager Blankenship gave Roberts his first day off in weeks “due to a mild sort of ruction,” Roberts turned in his uniforms.30 Blankenship tried to deal Roberts to Helena for Del Baker, but their manager, Charles Irby, would have none of it.31 Five years later the Missoulian would recall, “Missoula fans will remember that in 1912, after Skipper Roberts had one of his many clashes with everybody in sight,”32 and a touchy five days, Blankenship (who was now having to catch in addition to manage) returned Skipper’s uniforms and wrote him back into the lineup.33

Back in action on August 22 against John McCloskey’s Butte Miners, Roberts was immortalized in a “Hi Lander Hymn” within the Missoulian after he stole home:

Twas not a game to prompt a gloat,

But I am here to state

That Skipper got McCloskey’s goat,

That time he stole home plate.

Roberts beat out a bunt, was sacrificed on another bunt, and took third on a fielder’s choice. He then stole home for the third time in 1912 when the Ogden catcher dropped a high delivery.34

While the Highlanders of 1912 were a team not without their fair share of team theatrics, they were a championship caliber club, whose early lead in the standings was never really in jeopardy. Backed by pitchers “Bullet” Joe Bush, Carl Druhot, and Carl Zamloch the Missoula club clinched the pennant with a week of games left to play.

The day after the season ended, Union Association President and “minor league mogul” W.H. Lucas died suddenly in Missoula.35 Roberts was no doubt at the well-attended funeral, as he stuck around Missoula long enough to wager “a big roll” on the Red Sox over the Giants in the 1912 World Series. “It may be remarked that [he] is now a man of immoderate wealth. He had all the family silver and heirlooms on” Boston coming out on top.36

Despite their differences, Roberts was one of the first men signed by Blankenship for 1913.37 Coming off his best season to date, Roberts had ideas of how to take his game to the next level, “I have been swinging too hard at the ball, and I’ve been chopping a little too. This year I’m going to swing easier and just meet the pill. I know it will. I’ve got a new style of club too, and it’s just the stuff. Last year I never went to bat twice in succession with the same stick. That hurts a fellow’s hitting, you know.” The local paper liked the fiery player, “the Skipper is really a good, natural batter, but he seems to have hard luck, and to take bad slumps. They don’t make better receivers. The Skip has a beautiful wing, is a steady backstopper, and runs bases like a wild man.”38

When a late April snow storm pushed back the start of the 1913 Union Association, Roberts and a teammate chartered a snowplow and drove it around the streets of Missoula. A month into the campaign Blankenship was getting letters inquiring into what he wanted for his catcher.39 Credited with discovering Walter Johnson in Weiser, Idaho, Blankenship, once so eager to get rid of his team nuisance, was a man who knew how to milk the major-league clubs for more money. In the meantime, Blankenship fell ill and acting manager Nig Perrine and Roberts got into an on-field altercation over Roberts’s choice of words in trying to soothe the nerves of a young pitcher.40 That same week, Roberts was fined $5 by umpire Ralph Frary for persistent arguing.41

A week later the Highlanders were in Salt Lake for a series with the Skyscrapers. Cardinals manager Miller Huggins called upon Salt Lake’s manager John McCloskey to get his opinion of Roberts. Blankenship was quoted at the same time that he had letters inquiring about Roberts from three different managers, including Connie Mack.42 Umpire “Rasty” Wright, a veteran of both major leagues, “considered Roberts the best mechanical catcher in the world. ‘I have seen the best of them work, and I never saw a catcher who could compare with Roberts.”43

The Missoulian jumped on board, “[Roberts] is twice the ball player that either Bush or Zamloch ever will be. Roberts will outshine them both, two to one.”44 With attendance down in Missoula as the defending champs muddled through games at 13-17, and team president Hugh Campbell pressed for funds, Missoula chose to sell Roberts outright to the Cardinals for $3,000. The dough surely helped the team make payroll, but losing one of the team’s lone bright spots—Roberts was leading the league with a.440 average—only made matters worse.45 When McCloskey next came to Missoula his first question was what happened to Roberts, remarking, “Huggins is sure a wise old fox to grab a man like that.”46 Roberts’s contract while with St. Louis was for $225 a month, exactly double what he made with Helena in 1911.

Skipper made his major-league debut on June 12, 1913 at home against the Phillies. Catching Sandy Burk the last two innings and squatting in front of Hank O’Day, Roberts went hitless against Hall of Famer Pete Alexander.47 Five days later Roberts drew a walk off Earl Yingling, and scored his first big-league run. His first hit in the majors came the next day off Pat Ragan.

Skipper Roberts made his first big-league start on June 26, catching Slim Sallee. The Washington Herald thought, “Skipper Roberts, the new catcher of the Cardinals, [was] an exact replica of Frank Roth.”48 Used primarily as a pinch-hitter, and late-inning substitute, Roberts made just five starts with four coming over a two-week span starting August 26. This was also the date of Roberts’ only multi-hit game of the season, the achievement coming at the lefty-friendly Baker Bowl.

On September 12 Roberts was released to Indianapolis, but didn’t clear waivers with two different clubs.49 Soon after his peculiar way of talking landed him in the pages of The Sun:

The other day an opponent made a long hit early in the game. Roberts admired the feat.

“T-t-that was s-s-some hit,” he observed.

Manager Huggins was filled with wrath. “You big stiff, don’t encourage the other guys,” he grumbled, “pan ’em.”

Roberts didn’t answer. In the eighth inning he chanced to pass Huggins and the rival player at the same time. Turning to the manager he remarked:

“I s-s-still contend t-t-that was s-s-some hit.”50

Roberts appeared in his last game with the Redbirds in the first game of a September 21 doubleheader with Boston. Boston Braves left fielder Joe Connolly broke his ankle, and Roberts’s teammate with Missoula, Harry Trekell, was on the hill for the Cardinals. Roberts struck out pinch hitting in the ninth, and his season was over. Both St. Louis franchises finished in last place of their respective leagues, but the Cardinals were the worst team in baseball. Losing 99 games, they finished 49 games back of the New York Giants.

Wintering back in Montana (both Missoula and Lewistown) Roberts was employed with the Milwaukee Railroad in their sales department.51 He told the Missoulian, “I have seen the east and I don’t like it. I’m a western man.”52

The offseason saw Roberts sold by St. Louis to Oakland, but instead of heading farther west he announced his signing with the Pittsburgh Rebels of the upstart Federal League on March 4.53 Roberts appeared in 52 games for the Rebels, making nine starts, while backing up Claude Berry.

In a letter to friends back in Missoula, Roberts relayed that he had hurt his arm while in Lynchburg, Virginia, and went to see Bonesetter Reese. The good doctor charged Roberts $20 for putting two ligaments back in place.54

Less than a month after getting his arm looked at, Roberts was in a bar fight with Kansas City Packers pitcher Chief Johnson.55 It’s unknown what provoked such an altercation. Records show that Roberts never faced Johnson on the diamond. The two clubs did play a pair of three-game series over a two-week period around the time of the incident, but Johnson didn’t pitch in any of these games. Roberts made a single pinch-hit appearance in the first of the six games on May 4, in which he and teammate, pitcher Willie Adams, were ejected by home-plate umpire Garnet Bush for bench jockeying. Bush and Roberts had history, as the catcher had been ejected days earlier after he argued a Bush call at first base.

“Fired” by Pittsburgh manager Rebel Oakes after the fisticuffs, for what was “the last straw to a load of offenses that Roberts had been piling up ever since he arrived at the training camp,” Roberts signed with Joe Tinker and the Chi-Feds, suiting up for games at brand new Weeghman Park. After getting into just four games with Chicago, Roberts met with Federal League President James A. Gilmore, was warned that the “rough stuff” wouldn’t be tolerated, and sent back to Pittsburgh.56

In the second game of a doubleheader against those same Kansas City Packers on September 12, Roberts hit his only big-league home run, an inside-the-park variety off fellow Union Association alum Dwight Stone.57

Skipper Roberts made his last big-league appearance starting the second game of a doubleheader against Buffalo the day before the last game of the year. He caught George LeClair and went hitless as Fred Anderson shut out the Rebels in a twilight-shortened six-inning affair.

After being released by Pittsburgh, several papers reported that Roberts had signed with the Newark Pepper back in the Federal League. With Bill Rariden appearing in 142 games at catcher for Newark, there was little room for Roberts, and by mid-June he was released.58 In fact, the author could find no sign of Roberts playing professionally in 1915. Sporting Life reported in February that Skipper had gone into business with his father back in Spokane, which more than likely meant more time in the city league.59

Roberts was given his unconditional release by Miller Huggins in early April of 1916.60 Initial reports were that Roberts might retire, but he was half of the opening day battery for Tacoma at the end of the month.61 By mid-June Roberts was looking for a job again, this time with the Seattle Giants, but to no avail.62 He caught in a couple games back in Spokane, but was again let go.63

By the end of June, Roberts was with his third Northwestern League team, this time back in Montana with Butte.64 He appeared in 68 games for Manager Joe McGinnity that included catching the 45-year-old Iron Man and eventual Hall of Famer. But the two weren’t a match made in heaven. Accused of not staying in shape or playing his best ball, Roberts was threatened with release. During a game on August 18, tensions between manager and catcher boiled over on the field and into the clubhouse where the pair mixed it up in a brawl that involved biting. The former boxer seemed to get the best of things as he “jolted McGinnity about the eyes with a few well directed haymakers,” until the manager bit Roberts on his fingers. In the end McGinnity held the purse strings, and Roberts was fined $25 and suspended indefinitely.65 In the first week of September, Roberts was in a Butte court room for assaulting a different copper city citizen.66

Offered a job in Oakland by Del Howard for 1917, Roberts failed to report. By now his reputation for fighting his way off teams followed him in the papers.67 Roberts stuck around Butte in 1917, playing in some games with the Knights of Columbus, and umpiring a game between the Butte Bob Cats and the Colored Giants.68 The most fun the Skipper had in the summer of 1917 came as part of a sheriff’s posse.

On May 18 just before midnight, four highwaymen robbed six automobiles (carrying between 20 to 30 passengers) at the Three-Mile House outside Anaconda. Alerted to the robberies, three officers, accompanied by Skipper Roberts with revolver in hand, encountered the assailants as they hastily made their way through the streets of Butte. Gunfire erupted as the sheriff’s posse attempted to stop the speeding sedan with one of the robbers shot in the left shoulder by Deputy O’Connor’s Remington Model 11 “scatter gun.” The bandits made the corner, killed the lights, and two of the four escaped on foot with much of the booty. After the posse passed in would-be pursuit, the other two outlaws abandoned the car near the Edwin Block at the corner of Galena and Dakota. Around 3 A.M. deputies were able to apprehend the driver of the vehicle (who had been offered $20 for his services) after his accomplice was found on a street corner eating a bowl of chili. The day after the melee, Butte’s Sheriff O’Rourke expressed appreciation to Skipper Roberts, who just happened to be in the office when the call came in, “and promptly volunteered [his] services on the hazardous mission.”69

In 1918, “Skipper Roberts tried to enter the US aviation service, but his stammering kept him out of service.”70 It is with this that Roberts drops out of the available newspaper records.

Four years earlier on June 22, 1914, Skipper had married Ethel Mae Marjorie J. Driscoll of Creston, Iowa. His Pittsburgh teammates provided the newlyweds with a chest of silver.71 By 1920 the Roberts had moved to Contra Costa, California, where Skipper worked as a mechanic in the ship yards. By 1930, Skipper was working for Shell Oil as a machine operator at a refinery in Long Beach. Mae died October 29, 1937.

On Christmas Eve 1963, “Skipper” C.A. Roberts (as his headstone reads at All Souls Cemetery in Long Beach) choked to death on a piece of steak. A coroner’s autopsy revealed that Roberts had acute alcohol intoxication.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and fact-checked by Terry Bohn.

Sources

In preparing this biography, the author relied primarily upon online newspaper archives including The Sporting News offered at The Paper of Record, The Sporting Life made available through SABR membership, as well as the Library of Congress hosted Chronicling America newspapers, and Digital Library of Marriott Library at the University of Utah. Additional information was obtained from the player’s file at the Hall of Fame Museum and Library in Cooperstown. Census data was acquired from familysearch.org.

Notes

1 “World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918,” digital images, familysearch.org (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-81WM-33H?cc=1968530 : accessed 08/29/2017), Clarence Ashley Roberts, serial no. 4192, order no. 174, Draft Board 25-14-A, Butte, Silver Bow, Montana.

2 Spokane’s preeminent baseball historian, Jim Price’s research has Roberts with semipro teams Ware Brothers (a hardware store specializing in hunting and fishing gear) in 1902, and Powell & Sanders (grocery wholesale house) in 1907.

3 “Taking Candy from Babies,” Spokane Press, June 24, 1908.

4 “Indians Skin Cats Clean,” Spokane Press, June 26, 1908.

5 “Catcher’s Hoodoo Tackles Roberts,” Spokane Press, July 8, 1908.

6 “Tigers Get Bone to Chew,” Spokane Press, July 6, 1908, and “The Campbells are Coming,” Spokane Press, August 13, 1908.

7 “Long Smash Wins One,” Spokane Press, October 2, 1908.

8 “Silver Diggers are Playing Good Ball,” Spokane Press, September 16, 1908.

9 “Wichita Signs a Catcher,” Topeka State Journal, December 3, 1908.

10 “Jobbers Get Car Fare,” Topeka State Journal, March 18, 1909.

11 “Western League Notes,” Topeka State Journal, May 26, 1909.

12 “State Leagues,” Topeka State Journal, August 4, 1909.

13 “Kansas State League Games,” Topeka State Journal, August 5, 1909, and “State Leagues,” Topeka State Journal, August 6, 1909.

14 “Blankenship Behind Bat,” Spokane Press, September 8, 1909, and “Tigers Whitewashed,” Tacoma Times, September 8, 1909.

15 “Notes of the Diamond,” Salt Lake Tribune, April 11, 1911.

16 “Notes from the Anvil Chorus,” Daily Missoulian, September 28, 1913.

17 “Skipper Roberts Heads Batters at Boise,” Daily Missoulian, July 28, 1911.

18 “As It Looks,” Daily Missoulian, May 1, 1912.

19 “Ames Beats Boise Twice,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 31, 1911.

20 “Missoulian Picks League’s Class as Team,” Daily Missoulian, September 12, 1911.

21 “Local Fans Ready and Everything Else, Too,” Daily Missoulian, March 7, 1912, and “Skipper Sets Sail,” Daily Missoulian, December 9, 1911.

22 “Home Bugs Admire Missoula Club at the Park,” Daily Missoulian, April 17, 1912.

23 “Highlanders Take Second Contest from Butte,” Daily Missoulian, April 25, 1912.

24 “Skipper Roberts Shines,” Daily Missoulian, May 1, 1912, and “Butte Fans Shiver Through Lost Game,” Daily Missoulian, May 2, 1912.

25 “Highlanders Ahead when Wet Crabs the Contest,” Daily Missoulian, May 22, 1912.

26 Daily Missoulian, May 26, 1912.

27 “As It Looks,” Daily Missoulian, June 23, 1912.

28 Daily Missoulian, June 24, 1912.

29 “As It Looks,” Daily Missoulian, June 26, 1912.

30 Daily Missoulian, August 17, 1912

31 “Diamond Dust,” Salt Lake Telegram, August 21, 1912.

32 “Del Baker Sold to San Francisco Team,” The Daily Missoulian, January 10, 1917.

33 Daily Missoulian, August 22, 1912.

34 “Roberts Steals Home,” Daily Missoulian, August 23, 1912.

35 Joe Niese, “Early 20th century minor league mogul had ties to Chippewa Falls,” Chippewa Herald, June 12, 2012; Daily Missoulian, September 16-19, 1912.

36 Daily Missoulian, October 17, 1912.

37 “Some New Men Introduced by Manager Blankenship,” Daily Missoulian, March 1, 1913.

38 “Helped by Good Weather Blank Puts His Players Through Hard Workout,” Daily Missoulian, April 5, 1913.

39 “Foster Out of Missoula’s Line-up,” Ogden Standard, May 22, 1913.

40 “Missoula Once More Lands on Ogden,” Ogden Standard, May 23, 1913.

41 “Game Won in Ninth by Ogden,” Ogden Standard, May 24, 1913.

42 “Offer Ball Player,” Ogden Standard, June 4, 1913.

43 “Miller Huggins Asks for a Price on Our Blonde Catching Phenom,” Daily Missoulian, June 4, 1913.

44 “Roberts is Sold Outright,” Daily Missoulian, June 5, 1913.

45 “Skipper Roberts Leads League At Bat,” Daily Missoulian, June 11, 1913, and Gunnison Valley News, July 12, 1923.

46 “Two Changes in the Lineup of the Highlanders Today,” Daily Missoulian, June 10, 1913.

47 Daily Missoulian, June 13, 1913.

48 “Bits of Baseball,” Washington Herald [Washington, DC], June 24, 1913.

49 “Indianapolis Gets ‘Skipper’ Roberts,” Salt Lake Tribune, September 13, 1913, and “Diamond Dust, Salt Lake Telegram, November 8, 1913.

50 “Notes from the Anvil Chorus,” Daily Missoulian, September 28, 1913.

51 “Roberts Likes Lewistown,” Daily Missoulian, November 14, 1913.

52 “’Skipper’ Returns,” Daily Missoulian, October 19, 1913.

53 “Bags Two Players,” Daily Capital Journal, December 15, 1913, and Salt Lake Tribune, December 21, 1913, and “Skipper Roberts Jumps,” Salt Lake Tribune, March 5, 1914, and “Skipper Roberts to Federals,” Topeka State Journal, March 5, 1914.

54 “Diamond Dust,” Salt Lake Telegram, May 6, 1914.

55 “Still Ball Club Here,” Daily Missoulian, January 16, 1917, and Sporting Life, May 16, 1914.

56 Evening Capital News, May 22, 1914.

57 “Even Break at Pittsburgh,” Evening Star [Washington, DC], September 13, 1914.

58 Salt Lake Telegram, June 17, 1915; Clearwater Republican [Orofino, Idaho], June 11, 1915; Evening Capital News [Boise, Idaho], March 31, 1916.

59 Sporting Life, February 6, 1915.

60 Evening Star, April 6, 1916.

61 “Game On!,” Tacoma Times, April 28, 1916.

62 “Skipper Roberts Let Out By Tigers,” Seattle Star, June 19, 1916.

63 “Diamond Dust ,” Salt Lake Telegram, June 22, 1916.

64 “Butte Trades Players With Great Falls and Gets Shortstop Healey,” Seattle Star, June 23, 1916.

65 Sporting Life, September 2, 1916 & Salt Lake Telegram, August 22, 1916, and “Seen through the Sport Periscope,” Salt Lake Herald, September 2, 1916, and “Skip Roberts is Prodigal,” Daily Missoulian, February 17, 1918.

66 “Diamond Dust,” Salt Lake Telegram, September 9, 1916.

67 Daily Missoulian, July 22, 1917, and Butte Daily Post, August 27, 1917.

68 Daily Missoulian, July 22, 1917.

69 “Wounded Bandit Tells of His Part in Auto Robberies at Anaconda,” Butte Daily Post, May 19, 1917.

70 “Stove League Gossip,” Salt Lake Herald, February, 2, 1918.

71 Evening Capital News, June 30, 1914, and “The players of the Pittsburgh Fed team presented the couple with a chest of silver.” “Robert is Married,” Omaha Daily Bee, July 8, 1914, and “’Skipper’ Roberts is Now a Married Man,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 12, 1914.

Full Name

Clarence Ashley Roberts

Born

January 11, 1888 at Wardner, ID (USA)

Died

December 24, 1963 at Long Beach, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.