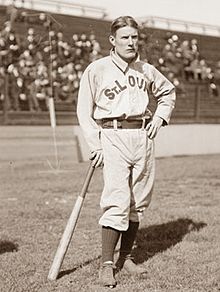

Spike Shannon

William Porter Shannon, known from his teenage years as “Spike,” loved football but instead spent a career in baseball. A quick glance at his record shows a short major-league career of five years between 1904 and 1908. A closer look at his minor-league career reveals six years with several minor-league clubs before 1904 and four years in the minors after 1908 for a playing career of 15 years. Less well known are his 18 years as a minor-league umpire and his offseason football career which must be explored to give a better appreciation of his life in sport.1

William Porter Shannon, known from his teenage years as “Spike,” loved football but instead spent a career in baseball. A quick glance at his record shows a short major-league career of five years between 1904 and 1908. A closer look at his minor-league career reveals six years with several minor-league clubs before 1904 and four years in the minors after 1908 for a playing career of 15 years. Less well known are his 18 years as a minor-league umpire and his offseason football career which must be explored to give a better appreciation of his life in sport.1

Like many players in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, Shannon trimmed several years off his true age, so that when he finally got his first chance in the major leagues he was viewed as a 26-year-old promising outfielder rather than a 29-year-old has-been. Until just recently baseball reference sources listed his birthday as February 7, 1878, but genealogical work by his great nephew, Bart Murphy, and SABR researcher Bill Lamb have confirmed he was actually born three years earlier, on February 7, 1875 in Clarksburg, Indiana County, Pennsylvania.2

Not much is known about Shannon’s early years. His father, Oliver D. Shannon, served as a private in the 78th Pennsylvania Infantry during the Civil War. After the war he became a blacksmith and married Rachel Cunningham. A daughter Sarah Bertha was born in 1868, a son Samuel Irwin in 1872, and William Porter in 1875. Oliver D. Shannon died on August 3, 1881, shortly before attaining the age of 40. William Porter Shannon was able to attend school through the fifth grade, but at around age 11 in 1886 he had to drop out of school and join the workforce along with his brother, sister, and his mother in order to support himself and his family.

William Porter Shannon got a break in the fall of 1896 when he was allowed to enroll at nearby Grove City College. College archivist Hillary Walczak has discovered the following about Shannon at Grove City: “He is listed as being part of the preparatory department in 1896-97. This was a prep school for the college. During this time there were not a lot of standards in secondary schools so kids would graduate high school, come to college but not be quite ready. So Grove City ran a prep school to try and get them on course for college. In 1897-98 he is an unconventional student of the business department. This basically means he wasn’t a full time student but was taking classes in the business department. In 1899-1900 he again is listed as an unconventional student of the business department. He is not listed after this point. Usually those who enter the prep school never fully enroll in the college. Often they get the required courses for the career path they are seeking and leave after they have achieved them without getting a degree.”3

Shannon played football at Grove City College for three seasons, 1896-1898. A perusal of Pittsburgh area newspapers reveals Shannon played at least three games for Grove City College in 1896, four games in 1897, and five games in 1898.4 While a number of Grove City College games may not have been reported in the local press or simply overlooked, Shannon was often hurt from action on the gridiron. In an interview in 1932 Shannon said, “I really liked football better than baseball despite the fact that I broke both legs, four ribs, and two fingers on the gridiron.”5 In the fall of 1899, Shannon played at least three games for the semipro Verona Indians. Shannon was primarily a halfback and had several games with several touchdowns.

Although he always maintained a fondness for football, Shannon began to realize that baseball was where he could earn his living. It is likely he played some amateur baseball in the 1890s, probably in the Butler, Pennsylvania area. His professional career began in the spring of 1898 when he signed with Charleston, South Carolina of the Southern League. His stay there was short, only 29 games, but he sported a .338 batting average with 10 stolen bases. The club folded in late May and Shannon was quickly signed by the Richmond, Virginia team of the Atlantic League. In 103 games Shannon batted .287 and stole 22 bases while at times playing spectacularly in the outfield. Shannon’s second season in organized baseball, 1899, saw him split the season between Richmond (80 games) and the Syracuse Stars of the Eastern League (33 games). He stole 34 bases, batted .230, and had a slugging average of only .270 (14 extra base hits).6

Several stories circulated in the press during Shannon’s lifetime on the origin of his nickname. To this writer the name “Spike” was obvious since photographs of Shannon revealed a man with an extremely square jaw. One story claimed that Shannon, as a young player, was unusually clumsy and spiked more than his share of opposing basemen. If true, Shannon quickly mended his ways as no evidence has been uncovered concerning spiking incidents involving Shannon. The most likely story is that Shannon wrenched his knee playing football and constructed a wooden knee brace secured with a couple of spikes and thereafter was known as “Spike Shannon.” In his early days at Grove City College he is sometimes referred to as Porter Shannon but that name quickly faded as “Spike Shannon” made a name for himself on the gridiron and the ball field. Several news accounts later in his career claimed even his family called him “Spike” and didn’t remember his real name, which is somewhat difficult to believe.7

During the 1900 season, Shannon started with Syracuse, playing seven games between April 26 and May 7. He then moved to Jersey City, of the Atlantic League for 11 games between May 10 and May 29, and four games with Harrisburg, of the same league, between May 31 and June 9. The Atlantic League folded in early June and shortly thereafter Shannon was acquired by Meriden of the Connecticut State League. In 73 games for Meriden, Shannon batted .288 and stole 36 bases. He remained as an outfielder throughout his playing career.

In 1901 Shannon moved west, playing 66 games for Indianapolis of the Western Association and 57 games for St. Paul of the Western League. Even though Indianapolis, often called the Hoosiers, were in first place on July 11 with a record of 47 wins and 25 losses the franchise folded and some of the players were cast adrift. Some players remained with the Matthews, Indiana, team which took the Hoosiers place in the league for the rest of the season. In one of the more consequential transactions in Minnesota baseball history, free agents and Indianapolis teammates Spike Shannon and Mike Kelley were signed by the St. Paul Saints. While Shannon was a starting outfielder for the Saints for the next two and half years and had his major-league career ahead of him, it was Kelley, who was a first baseman at the time, who had the greater impact. Kelley had three terms as manager of the Saints (1902-1905, 1908-1912, 1915-1923) and then moved over to manage (1906, 1924-1931) and then own the Minneapolis Millers (1932-1946). During the offseason Shannon had not shaken the football bug, playing several games, at least, for the semipro St. Paul Tigers in the Fall of 1902 and 1903.8

Shannon’s 1902 and 1903 seasons with the St. Paul Saints were among the most productive of this career. In 120 games in 1902, Shannon batted .344 and stole 41 bases for the Saints who finished in third place with a record of 72 wins and 67 losses. In 1903 the Saints captured their first American Association pennant with a record of 88 victories and 46 defeats, winning the flag by 4 ½ games over Louisville. Shannon led the league in runs scored with 132, matched his 1902 stolen base mark with 41 thefts, and batted a solid .308. That fall Shannon was picked up in the minor-league rule-five draft by the St. Louis Cardinals, somewhat helped by the fact that the Cardinals believed he would turn 26 years of age during the offseason rather than age 29. On a personal level, Shannon met Sarah Ellen (Sadie) Murphy while in St. Paul and married her in 1903. They remained lifetime companions, with Sadie following Spike in all his baseball and offseason activities for the next 37 years. 9

In 1904 the St. Louis Cardinals finished in fifth place with a record of 75 wins and 79 defeats, 31 ½ games behind the New York Giants. It was a move in the right direction as they had finished in last place the year before. Shannon was the regular right fielder for the Cardinals, appearing in that position in 117 games, while also seeing time in left field (13 games), and in center field (3 games). Shannon had 18 assists and was involved in 10 double plays in 1904. On the batting side he batted .280 but only had 14 extra-base hits for a .318 slugging average. Spike stole 34 bases and scored 84 runs with 500 at-bats in 1904.

In 1905 the Cardinals slipped backwards, ending with a record of 58 wins and 96 defeats in a sixth place finish. Shannon played in 140 games as the Cardinal left fielder and was a top of the order guy who was expected to get on base somehow, steal some bases, and score runs on hits by other teammates. He had little power. His 162-game average throughout his major-league career was only 11 doubles, four triples, one homer, 89 runs scored, and 34 stolen bases. He struck out as often as he walked, an average of 67 each for 162 games.

During spring training of 1906 new Cardinals manager John McCloskey named Shannon the new field captain of the St. Louis nine. The prevailing opinion was that captains should be infielders and experienced major leaguers so this move by McCloskey raised some eyebrows. 10 Despite this honor, Shannon apparently had a personality conflict with McCloskey and as the season wore on his days in St. Louis were numbered. On July 13, 1906 he was traded to the New York Giants for Sam Mertes, Doc Marshall, and a reported $10,000.11 While Mertes and Marshall did not last in St. Louis, the money received from the Giants apparently helped keep the Cardinal franchise afloat. Shannon’s 1906 statistics were almost evenly split between St. Louis and New York. Spike played in 80 games as the Cardinal left fielder and 76 games as the Giant left fielder. On the season he had 589 at-bats, stole 33 bases, and knocked in 50 runs. His batting average slipped to .256 and his 10 extra-base hits were pathetic, even by dead ball standards.

Shannon became a very popular player as a New York Giant. In addition he was more helpful to young players than the average veteran player as this quote from Fred Snodgrass reveals, “The Giants then had mostly rough and tough old characters, men who had been around quite a while — men like Mike Donlin, Joe McGinnity, Cy Seymour, Spike Shannon, and a lot of others. When I came up in 1908 it was mostly a team of veterans, a lot of them nearing the end of their baseball careers. But that didn’t mean they accepted that fact. And yet, when I look back, I realize that I owe a great deal to one of those veterans. I was assigned to room with Spike Shannon. He was about thirty years old and had been an outfielder in the Big Leagues for about five years. He took me under his wing, helped me, encouraged me and told me what to do and what not to do. I doubt if I’d have made the club that year if it hadn’t been for Shannon.”12

Shannon was a left-handed batter who had trouble pulling the ball and the Cubs shifted their infielders according to Joe Tinker. Tinker said, “For instance, McGraw had a fellow named Spike Shannon, an outfielder, who could not hit one ball in ten to right field, even though he was a left hand hitter. Steinfeldt, our third baseman, used to move over toward third base; I would pull over near him, and Evers would come close to second, for it was almost impossible for Spike to hit the ball any other direction.”13

Throughout his career Shannon was known for making spectacular catches in the outfield. He was known for playing the sun field (left field) at the Polo Grounds especially well, at least compared to his predecessors. Shannon’s biographical file at the Hall of Fame library contains an undated clipping (probably from early April 1907) of an exhibition game at Newark where Shannon made a spectacular catch, “Eyman was in the grand-stand when Shannon, the Giants’ left fielder, made a run for the line drive hit by Sharp of the Newarks. Shannon stopped at the left field behind which there was a crowd. Then he made a leap and fell, turning a somersault and rolling to the ground, but holding to the ball. It was a most sensational play. The five thousand spectators yelled, and Mr. Eyman tried to join the tumult, but the excitement was too much for him and he sank back unconscious. He was attended by a physician and later to the hospital.”14

Shannon led the National League in runs scored in 1907 with 104 runs and played in every game. However when he injured himself while running into the wall in June 1908 his days as a Giant were numbered. John McGraw put Shannon on waivers and on July 22 the Pirates picked him up for the $ 1,500 waiver price. The Pirates didn’t realize the severity of his injury and he limped through the rest of the 1908 season, playing only in 32 games for the Pirates, batting a paltry .197.

Over the winter the Toledo Mud Hens were interested in Shannon, but instead the Kansas City Blues of the American Association acquired Shannon’s services for the 1909 season. Shannon was a regular outfielder for the Blues in 1909 and 1910, appearing in 162 games in 1909 and 169 games in 1910. He stole 31 bases while batting only .210 for the eighth-place Blues in 1909. In 1910 the Kansas City club improved to 85 wins and 81 losses and a fifth-place finish, with Shannon improving his batting average to .247. Nearing the end in 1911, Shannon appeared in only 52 games batting only .216. Even though he remained on the roster, Shannon was left home on several road trips by manager Danny Shay, who had been his teammate in St. Paul in 1902, St. Louis in 1904-05, and with the New York Giants in 1907. Shannon sat out the 1912 season, when Shay found him a job clerking in his Kansas City hotel.

By the time the spring of 1913 rolled around Shannon had the urge to play again and applied for the St. Paul manager’s job in the re-organized Northern League. That job went to Charlie Jones but on March 12, Shannon’s persistence paid off when he was named manager of the Virginia, Minnesota Ore Diggers of the same league. In addition to being a playing manager, Shannon was expected to recruit players as well and he only had about six weeks to assemble a competitive roster against some clubs that had been operating for several years. Shannon made several trips to Chicago and the Twin Cities on recruiting trips before the team assembled in early April for spring training in Rochester, Minnesota. During this time his wife, Sadie, was hospitalized with appendicitis. 15

The Virginia management was either unwilling or unable to assemble a competitive team. They seriously underestimated the quality of players throughout the league. Shannon, as a 38-year-old center fielder on gimpy legs, still was among one of the better players on the Ore Diggers roster. They simply did not have enough talent to compete. Despite signing Rube Waddell, Bobby Roth, and Tony Faeth, to name three players that had played or would play in the major leagues, the Ore Diggers compiled a 15-40-1 record by July 1 when Shannon was dismissed. He caught on and played seven games with St. Paul between July 13 and July 20 but not before spreading a story among the local Virginia newspapermen that he had bought the struggling St. Paul Northern League franchise. Most newspapermen saw through the gag, one reporting that Shannon only owned the clothes on his back, but at least one newspaper reported the story. 16

Shannon began the 1914 season as an umpire in this same Class-C Northern League. He umpired a series in each league town, including a warm reception in Virginia, before getting a better offer from the Federal League. How does an umpire with a little over one month experience get a call from a supposedly major league? Shannon was good friends with Bill Brennan, a former National League umpire and now chief of umpires for the Federal League. Shannon and Brennan, a St. Paul native, had played football together 10 years previously for the semipro St. Paul Tigers.17 Shannon was called a traitor among some Northern Leaguers for this contract jump. Talk died down when league president John Burmeister declared Shannon had talked to him about the Federal League offer and he had granted Shannon his release. Shannon’s first game in the Federal League was on July 1, 1914, and his partner was Bill Brennan. In the remaining 93 games of the season Shannon was behind the plate 37 times and on the bases (first base), 56 times. Shannon was partnered with Bill Brennan through the games of July 30. His next partner was Barry McCormick (July 31-September 18). He finished the season paired with Al Mannassau (September 19 — October 10).

Shannon returned to the Federal League in 1915 and umpired in 84 games between the start of the season on April 10 and August 7. Only 11 of them were behind the plate. His partners during the season were Bill Brennan, Barry McCormick, and Jim Johnstone. Shannon missed a slew of games in May; only umpiring games on May 2, May 17, and May 21-24. He also missed several games in July (22-25). His last game was on August 7, 1915 when he and crewmate Jim Johnstone had to be escorted off the field after Newark fans rushed the field during a game against Kansas City. Double-headers at Pittsburgh on July 28 and 29 and in Kansas City on July 31 and August 1 might also may have exhausted Shannon.18

Shannon was out of baseball for almost a year and not much is known about his activities during this time. In July 1916 he became an umpire in the Class-A Western League. Since league cities were Denver, Wichita/Colorado Springs, Omaha, Lincoln, Sioux City, St. Joseph, Topeka, and Des Moines a more geographically accurate name for the league might have been “The Great Plains League.”

Shannon umpired in the Western League for four years, 1916-1919, most of the time as the sole umpire on the field. The league employed four to six umpires per season during this time and Shannon was occasionally paired with another umpire; usually Carney or Fillman. Besides Shannon other Western League umpires in 1917 were George W. Miller of Kansas City (also a 1916 umpire), W.T. Gaston of Byersville, Ohio, Mike Jacob of Louisville, John Fillman of Joplin, Missouri, and William McGilvray of Denver.19 In 1918 the Western League was among the first leagues to ban the spitball, two years before the major leagues.20 During the winter for several years, Shannon was a miner in Ottawa County, Oklahoma, a lead and zinc mining district, southwest of Joplin, Missouri, a league town.

In 1920 Shannon moved up a notch to umpire in the Class-AA American Association when Dave Altizer, a former Minneapolis Miller shortstop, decided he wanted to manage a club in Aberdeen, South Dakota instead. Shannon’s partner in 1920 was Frank Connolly and Shannon umpired in 173 games. Other American Association umpires in 1920 where W.F. Finneran, John “Buck” Freeman, James A. Murray, A.L. McGloon, Louis Knapp, and Charles McCafferty. The Connolly-Shannon crew umpired 29 games in Kansas City; 25 in Toledo; 24 in Minneapolis; 22 in St. Paul, Milwaukee, and Columbus; but only 17 in Indianapolis and 12 in Louisville. 21

In 1921 Shannon umpired 167 American Association games, primarily with George H. Johnson as his crewmate. Also in the American Association in 1922 Shannon’s partner was a man named Joe O’Brien.

In 1923, 1924, and 1925 Shannon was back in the Western League. The league used eight umpires in each of these three years. The 1924 umpires included Matty Fitzpatrick, Pat Donohue, Ed Gaffney, Otis “Ollie” Anderson, Gerald Hayes, H.R. Held, Pat Boyle, and Spike Shannon. League president Albert R. Tierney in announcing the 1924 umpires said the league would not automatically throw stained or nicked baseballs out of the game per a batter’s request in order to conform to the major league policy. This move was aimed at helping the pitchers.22 Shannon’s crew mates were Jensen in 1923, Pat Donohue in 1924, and Powell in 1925.

Shannon spent the 1926 baseball season as an umpire in the Pacific Coast League. He was not unfamiliar with California; having spending several winters as a player in the California Winter League, playing primarily for the Stockton club.23 The New York Giants conducted spring training in Los Angeles, California in 1907, when Shannon was the Giants’ regular left-fielder. His crewmates for 1926 were a man named Burnside and a man named Ryan.

In 1927 Spike Shannon became an umpire in the Southern Association. He was one of nine umpires employed by the Association that year. Three crews had two umpires and the fourth crew had a third umpire who would rotate among the crews during the season. Shannon was partnered with his Federal League and St. Paul football teammate Bill Brennan for most of the season. Other umpires were Steamboat Johnson, Buck Campbell, Bill Robertson, Bick Campbell, Buck Weaver, Ted Clark, and Hadley “Bulldog” Williams. 24

In 1928 Shannon was back umpiring in the American Association after a five year hiatus. His crew mate was his 1920 partner, Frank Connolly.

Spike Shannon was back to umpiring in the Southern Association in 1929. His partner for 1929 and 1930 was Jim “Death Valley” Scott. Late in the 1930 Shannon was involved in a game that got national attention. The first place Memphis Chicks were playing the second-place New Orleans Pelicans in New Orleans. A Memphis win would clinch the Southern Association pennant for the Chicks while a Pelicans win would keep their chance of overcoming Memphis for the title alive. Memphis had a 5-4 lead going into the bottom of the ninth inning but it was getting dark. The Pelicans began using every delaying tactic in the book in order to get the game called. Infielders would come in one player at a time to confer with the pitcher, the pitcher would step off and tie his shoe, etc. If the game was called the score would revert back to the end of the eighth inning when New Orleans had a 4-3 lead. Fans began to throw glass pop bottles on the field and the verbal abuse was increasing in intensity with every passing moment. Finally Shannon had enough and declared the game forfeited to Memphis and thus handing them the Southern Association pennant. One glass pop bottle hit Shannon in the head and at least two Memphis players were also beaned. Shannon had to been escorted off the field by the police and through a tunnel and out of the stadium for his own protection. Columnist William Braucher, in a syndicated column reprinted in many newspapers all over the country, recounted the scene and declared, “Spike Shannon found himself in a tough spot. But you’ll have to agree that by ordering that game forfeited, he proved himself a game guy.” 25

The 1931 season was Spike’s last season umpiring in organized baseball. He was again in the Southern Association as one of their eight umpires. The other seven arbiters were rookie umpire Jack Hovater, and veteran umpires John Quinn, E.L. Goes, H.T. “Buck” Campbell, Hadley Williams, Harry “Steamboat” Johnson, and Bill Brennan. Shannon was paired with Hovater most of the season. 26

After the 1931 season Spike retired from umpiring professional baseball and he and Sadie retired to his wife’s home town of Minneapolis. For the next three years Shannon was employed by the Lynnhurst Driving Tee, a golfing practice facility, at 56th Street South and Lyndale Avenue in Minneapolis. In 1935 he moved on to Dayton’s department store in downtown Minneapolis, where he was employed for the rest of his life. Spike did not entirely give up baseball; he managed the amateur Gerow’s baseball club in 1934, played in an all-star game in 1934, and in 1935 helped run some baseball clinics. 27Shannon enjoyed reunions with his old baseball teammates and opponents. He attended several meetings of “The Old Guards of the Diamond,” a group of old ballplayers that met annually in Minneapolis. His last reunion was on January 2, 1940 several months before his death on May 17, 1940. He was buried at St. Mary’s Cemetery in Minneapolis and his wife, Sadie, was buried alongside him in 1958. Sadie was a fan too; she attended her first game in 1896.28 The Shannons did not have any children.

One of the better tributes came from the Des Moines Register: “Old time fans will remember him as the ruddy faced Irishman who went about his business quietly and efficiently, taking abuse from fans and players, without apparent resentment. It was seldom that Shannon ever put a player or manager out of the park. The provocation was great indeed when he quietly informed a too demonstrative athlete that he was through for the day and would have to retire to the dugout. Spike was a witty Irishman, a little flannel-mouthed it is true, and it was his keen sense of humor that helped him over many rough umpiring spots. One of his favorite expressions when he referred to a good ball park, a fancy hotel lobby or his favorite tavern for drinking beer was: Ain’t this a garden spot?”29

Shannon was remembered fondly many years after his own death by at least one fan. In 1959 Mary McCandless, age 100, who grew up in Butler, Pennsylvania and was a Pirate fan, died in Tampa, Florida. Her daughter remembered how her mother “was on friendly terms with most of the old time baseball players. She told of going on picnics with Babe Ruth, Rube Waddell, Spike Shannon, Grover Alexander and others.”30 There is no easy way to verify these picnics. Memories of events and people in the distant past often become confused or the time sequence wrong in some way. However, the fact that Shannon was mentioned in the same sentence with Ruth, Waddell and Alexander is telling. in my opinion.

In 1911 there was a movie released entitled, Spike Shannon’s Last Fight. It was about a boxer of some renown, who gave up the ring for a woman who wanted him to quit after their marriage. After a few years of struggling with their finances, the woman becomes deathly ill. Spike returns to the ring, for one last time, to win money for her medical care. It is not known if the subject of this biography got any residuals for the use of his name, (unlikely) and he does not appear to be connected with this film in any way. Occasionally Shannon was referred to as an ex-pugilist and spent some training time with a punching bag, but there is no evidence he ever stepped into the ring for a professional fight. 31

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and fact-checked by Rob Wood.

Notes

1 Shannon’s playing record can be viewed at Baseball-reference.com. His minor-league record is incomplete and several teams are unrecorded. Note that he did not play in 1912 but resumed his playing career for one year in 1913. Except for his time in the Federal League, his umpiring career is being presented here for the first time.

2 The prime sources are the 1880 U.S. Census, which recorded the Shannon household in June of that year and William Porter Shannon is listed as five years old. The other primary source is Shannon’s World War I draft registration card which gives his birth year as 1875. Lying to Selective Service officials is a felony and at that time Shannon might, under the circumstances, have preferred to reveal his true age.

3 Email of December 11, 2017 between Hilary Walczak, Grove City College Archivist and SABR member Bill Lamb. In addition, there is no evidence of Shannon attending high school. The 1940 census lists his highest educational level as fifth grade.

4 Sources for Shannon’s football career at Grove City College, 1896-1899 are the Pittsburgh Daily Post and the Pittsburgh Press.

5 Minneapolis Tribune, June 12, 1932: 29, 31.

6 Shannon’s batting and fielding statistics can be found at Baseball-reference.com. For missing data, analysis of league box scores determined games played and time spans for particular teams.

7 Spokane Press, July 17, 1906: 4.

8 St. Paul Globe; October 19, 1902: 10; October 17, 1903: 5; November 20, 1903: 5.

9 No marriage record for the Shannons has been found. However, the 1910 federal census says they had been married for seven years. They would not have met until mid-summer of 1901 and evidence shows they were married by the spring of 1904.

10 Houston Post, March 2, 1906: 3.

11 Washington Post, July 17, 1906: 8.

12 Lawrence Ritter The Glory of Their Times (New York: MacMillan, 1966), 86-87. [Easton Press Edition, 1998

13 Joe Tinker, “Tinker to Evers to Chance,” Orlando Sentinel, May 8, 1931: 2.

14 “Fan Stricken as he Cheered Play.” Undated clipping in Shannon’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame library. [most likely early April 1907 in unnamed Newark newspaper.

15 The Minneapolis Tribune, March 27, 1913: 16.

16 The Daily Virginian (Virginia, Minnesota), July 12, 1913: 1.

17 St. Paul Daily Globe, November 20, 1903: 2.

18 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 8, 1915: 35. Federal League umpiring data was gleaned from day to day logs maintained by Retrosheet.org.

19 Minneapolis Tribune, March 18, 1917: 17.

20 Marshalltown Iowa Evening Tribune, April 13, 1918: 2.

21 The primary source for 1920 American Association umpiring data was the Indianapolis Star. Another couple of newspapers were consulted as well, including the Minneapolis Tribune and the St. Paul Pioneer Press.

22 Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln, Nebraska), February 27, 1924: 3. Other Western League information was gleaned from the Des Moines Register.

23 Los Angeles Herald, December 22, 1906: 8.

24 Source for Southern Association information was Atlanta Constitution.

25 William Braucher, “Hooks and Slides,” Denton, Texas Record-Chronicle, September 22, 1930: 6.

26 Pensacola News Journal, March 19, 1931: 6.

27 Minneapolis Tribune, May 12, 1934: 22 and June 30, 1935: 15.

28 Minneapolis Tribune, August 12, 1954: 13.

29 Des Moines Register, May 21, 1940: 9.

30 “Mrs. McCandless, 100, Dies, Was Sport Lover,” Tampa Bay Times, September 9, 1959: 23.

31 Mount Carmel, Pennsylvania Item, September 18, 1911: 4.

Full Name

William Porter Shannon

Born

February 7, 1875 at Clarksburg, PA (USA)

Died

May 16, 1940 at Minneapolis, MN (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.