Ted Lewis

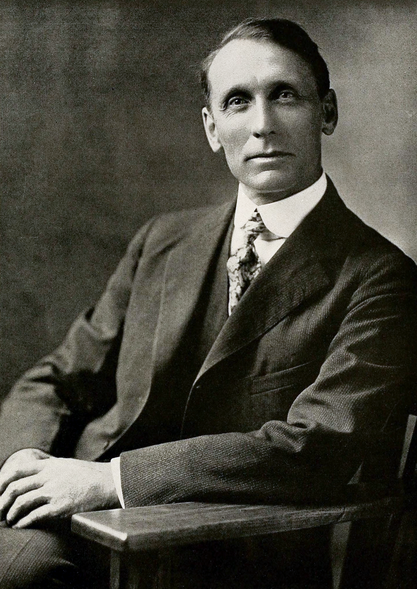

Williams College is best known in baseball circles for two nonplaying alumni: the last independent commissioner, Fay Vincent (1960), and the blustery Boss himself, George Steinbrenner (’52). There hasn’t been an Ephman in the majors since 1934, but Ted Lewis, “The Pitching Professor,” was not just the finest ballplayer Williams ever produced — like Sir Thomas More, he was a man for all seasons. Educator, elocutionist, natural leader — Lewis embodied an array of talents but always retained a winning humility.

Williams College is best known in baseball circles for two nonplaying alumni: the last independent commissioner, Fay Vincent (1960), and the blustery Boss himself, George Steinbrenner (’52). There hasn’t been an Ephman in the majors since 1934, but Ted Lewis, “The Pitching Professor,” was not just the finest ballplayer Williams ever produced — like Sir Thomas More, he was a man for all seasons. Educator, elocutionist, natural leader — Lewis embodied an array of talents but always retained a winning humility.

Horatio Alger could not have conjured up a life story like this, which has the power to make the most hardened cynic believe in ideals again. Edward Morgan Lewis was born on Christmas Day 1872 in Machynlleth, Wales. His parents were John C. Lewis and Jane L. (Davies) Lewis. When the boy was 8 years old, his family moved to Utica, New York, where they lived on the banks of the Erie Canal. Little Ted earned his first quarter delivering groceries for the local corner store (though he was docked if he broke a ketchup bottle), and scouted out other odd jobs, supplementing the immigrants’ straitened budget.

It is an article of faith that Welshmen have wonderful voices and a love of poetry, and the Lewis family reinforced this tradition. The great American poet Robert Frost was a crony of Ted Lewis’s for 20 years — even into their 60s, they played “singles” baseball or softball in the backyard whenever they got together. Frost read from Tennyson and Whitman at his friend’s memorial tribute, and his address showed the profound influence of culture on character:

“He told me once — I was afraid that the story might not be left for me to tell — that he began his interest in poetry as he might have begun his interest in baseball — with the idea of victory — the ‘Will to Win.’“He was at an Eisteddfod in Utica, an American-Welsh Eisteddfod, where the contest was in poetry, and a bard had been brought in from Wales to give judgment and to pick the winner; and the bard, after announcing the winner and making the compliments which judges make, said he wished the unknown victor would rise and make himself known and let himself be seen. (I believe the poems were read anonymously.) The little ‘Ted’ Lewis sitting there beside his father looked up and saw his father rise as the victor. So poetry to him was prowess from that time on, just as baseball was prowess, as running was prowess. And it was our common ground.”

Lewis worked as a bundle boy in a department store and as a surveyor’s helper, studying borrowed textbooks by lamplight. With the $50 in personal savings he managed to put aside, the youth entered Marietta College in Ohio, which gave him the opportunity to meet his tuition payments by working as a letter carrier, hotel clerk, and janitor.

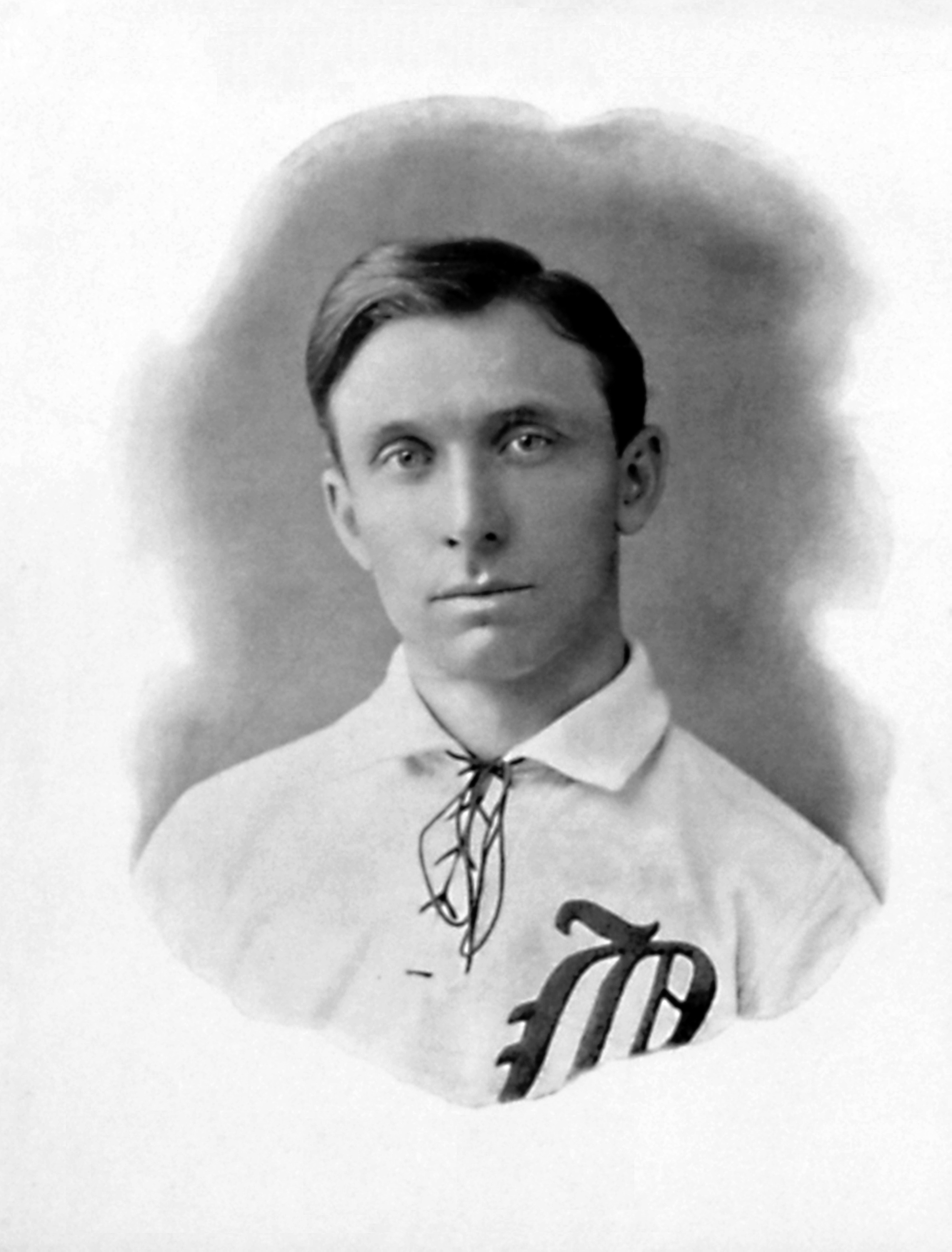

In the fall of 1893 sophomore Ted Lewis transferred to Williams, the small liberal-arts school nestled in the Berkshire Hills of western Massachusetts. He made a tremendous impression on his classmates, becoming president of the elite Gargoyle Society and winning the class cup in a walkover, receiving 32 votes while no one else got more than four. Lewis’s accomplishments on the mound were certainly a part of his status. In 1895 he won all eight games in the Triangular League (which then consisted of Williams, Amherst, and Dartmouth rather than Wesleyan), and he followed up with six more in his senior year.

Baseball was the most popular sport at the college in those days, and the Williams Weekly was full of manly exhortations to give full voice while cheering. The souvenir scorecard from the 1896 Commencement Game against Amherst is another charming curio, with Captain Ted’s photo on the front cover and official yells (Osky-wow-wow, Skimmy-wow-wow, Jimmy-wow-wow, W-O-W) on the back.

Lewis faced some most intriguing opponents besides Yale and Harvard. These included the original black pro team, the Cuban Giants, whose trip to the Purple Valley bears further investigation. Another was Louis Sockalexis, then the star center fielder for Holy Cross. A year before his briefly spectacular run with Cleveland, the Penobscot Indian “played a phenomenal game, catching and batting balls, whenever and wherever he pleased.”

During his college days, Lewis also won the heart of hometown girl Margaret Hallie Williams with a move that would have left Sir Walter Raleigh in the dust. At a local game in Richfield Springs, New York, he had promised her that he would meet her at the grounds and usher her in. But Margaret arrived a little late, while Ted was facing the first batter. Yet when he spied his wife-to-be, he calmly dropped the ball, walked off the hill (making the captain think Lewis had gone “bughouse”), and saw to his escort duties. The gallant then returned to a huge hand from the crowd.

Seeking money to further his studies, the graduate commenced his major-league career with the Boston Beaneaters. Frank Selee’s club was the class of the National League in the 1890s, winning five pennants behind numerous Hall of Famers and near-greats. Lewis was a key part of the last two titles, especially in 1898, when he led the league in winning percentage at 26-8. He also appeared in three games in the 1897 Temple Cup series, winning one, losing one, and allowing Boston to claw back from an early blowout into a near win with a strong effort in long relief. In 1904 Boston Globe sportswriter and old-time player Tim Murnane remembered Lewis as “a superb pitcher, with great curves and fine speed, both of which he used with rare judgment. He was a fine batsman for a pitcher and was a willing worker for his club.”

The “good guy” Beaneaters had an ongoing battle with John McGraw’s Baltimore Orioles, notorious for their ruffian tactics. “Parson” Lewis prefigured the fictional Yalie Galahad Frank Merriwell and McGraw’s Mr. Clean with the Giants, Christy Mathewson. A leading example of Lewis’s devotion to fair play came on August 24, 1901, when he helped rescue umpire Joe Cantillon from a mob of Boston fans who stormed the field. Tim Murnane stated, “It is doubtful if good, clean sport ever had a more earnest and successful practitioner than ‘Ted’ Lewis.” Echoing these sentiments, Damon Hall, a close friend from Williams, said: “One might have supposed in those earlier days of professional baseball that a college graduate who did not drink, who refused to play Sunday ball, who said his prayers and read his Bible daily, who even asked his teammates to go to prayer meetings with him, would have been esteemed somewhat of a prig by the other members of the squad. Instead, they took him to their hearts.”

Indeed, Ted had seriously considered entering the ministry but decided he could reach more young people through the classroom. While with Boston he found time to coach the Harvard nine. After jumping to the new American League in 1901 and playing with the very first Red Sox team (then known as the Americans, among other early names), Lewis retired from baseball to devote his full energies to teaching. His lifetime record was 94-64, with an earned-run average of 3.53 and a batting average of .223.

The Professor had earned his master’s from Williams in 1899, and from 1901 to 1903 he taught elocution at Columbia. His alma mater then lured him back to teach oratory for eight years, during which he also lectured at the Yale Divinity School. In 1910 the Welsh community of Berkshire County formed a society, acclaiming Lewis as president. For many years he would return to North Adams on St. David’s Day, March 1, to address his leek-waving brethren. (The only other major leaguer born in Wales was Jimmy Austin, who was one of Lawrence Ritter’s subjects in The Glory of Their Times.)

Also in 1910, Lewis ran for Congress as a Democrat in a staunch Republican district, and missed pulling off an upset by just 736 votes. He said, “It may be that I am starting in on this campaign in the ninth inning with the score 9 to 0 against me. But if the odds are against me I’ll play the game out, for you never can tell what a score you may make in the ninth.”

The next year, however, Massachusetts Agricultural College in Amherst beckoned. Lewis soon proved how capable an administrator he was, being pressed into service as acting president in 1913-14 (when he made another unsuccessful bid for Congress, supported by pioneering muckraker Ray Stannard Baker). The dean of languages and literature again stepped into the breach in 1918-19 and 1924, finally accepting the position of president officially in 1926. It was through his efforts that the modest “Aggie” school was transformed into today’s University of Massachusetts. Lewis felt uncomfortable with the political pressure there, however; there was an ongoing power struggle with the state government over funding and the authority of the Board of Trustees. Thus Lewis moved to the University of New Hampshire in 1927. But before he left, Massachusetts Agricultural College surprised its outgoing president by conferring upon him the honorary degree of doctor of laws.

Under the aegis of President Lewis, UNH, in Durham, New Hampshire, established a graduate school and broadened its infrastructure considerably, building the first women’s dormitory. In Durham Lewis received many of his famous friends, including Robert Frost. He had first met the then-unknown poet, a fellow MAC professor, in 1916 — and the Eisteddfod veteran delivered the first public reading of Frost’s verse. Forty years later, by then a grand American institution, Frost wrote about the 1956 All-Star Game for Sports Illustrated, also reminiscing about his pitching lessons from Lewis.

The UNH archives also show how Lewis knew and corresponded with US Presidents William Howard Taft (then chief justice of the Supreme Court), Calvin Coolidge (as vice president), Woodrow Wilson, and Franklin D. Roosevelt. There are letters from other well-known individuals in this special collection, including another chief justice, Charles Evans Hughes; polar explorer Richard Byrd; heavyweight boxing champion Gene Tunney; and Philadelphia Athletics manager Connie Mack.

Ted Lewis died at midnight on May 23, 1936, at the age of 63. His health had begun to fail about two years before, but even though the beloved “Prexy” was suffering greatly from liver cancer, he summoned up his old athletic reserves to climb the stairs to his office. In February he underwent an operation, and he rallied enough to make an appearance at UNH’s Opening Day ballgame versus Bates — pitched and won by future major leaguer Bill Weir. The students again took heart, but Lewis relapsed shortly thereafter. He was survived by his widow, Margaret; his two sons, Edward W. Lewis and John B. Lewis; and his daughter, Gwendolyn (Mrs. Samuel W. Hoitt).

Lewis was laid to rest in the Durham Community Cemetery on May 26, with former Boston teammate Fred Tenneyserving as one of the pallbearers. In a memorial tribute before the entire student body and faculty that afternoon, Robert Frost read his friend’s two favorite poems, Tennyson’s “In Memoriam” and Walt Whitman’s “On the Beach at Night.”

UNH sports teams still play today at the Lewis Fields, but this man’s most fitting memorial might be the measured question he always posed to his colleagues: “Well … what can we do to better the situation?”

An updated version of this biography appeared in “The Glorious Beaneaters of the 1890s” (SABR, 2019), edited by Bob LeMoine and Bill Nowlin. This biography also appeared in “New Century, New Team: The 1901 Boston Americans” (SABR, 2013), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Quotes on Ted Lewis, the ballplayer

Compiled by UNH alumnus Rich Eldred for his Lewis sketch in Nineteenth Century Stars (SABR, 1988):

“Teddy Lewis will pitch good ball for the Boston Americans no matter how many others may croak.” — Wilbert Robinson

“When at concert pitch there are few better than Lewis.” — Tim Murnane, Boston Globe

“Lewis was steady as a minister should be. … Chicago’s heaviest hitters went down before his speedy deliveries like corn stalks before a gale.” — Jake Morse, Boston Herald

“Parson Lewis is closing his career in a blaze of glory.” — Boston Globe after Lewis beat Nixey Callahan with a two-hitter in his final game

Sources

Ted Lewis File at National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York.

Ted Lewis File at Williams College Alumni Association, Williamstown, Massachusetts. (Includes a typewritten manuscript of “Edward Morgan Lewis, Early Career” by his younger relative Hobart L. Morris Jr.)

Obituary, New York Times, May 24, 1936.

Online census records, 1910 and 1920.

“In the Loop,” News for Staff and Faculty, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, May 18, 2004.

Online records, University of New Hampshire.

Full Name

Edward Morgan Lewis

Born

December 25, 1872 at Machynlleth, Powys (United Kingdom)

Died

May 23, 1936 at Durham, NH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.