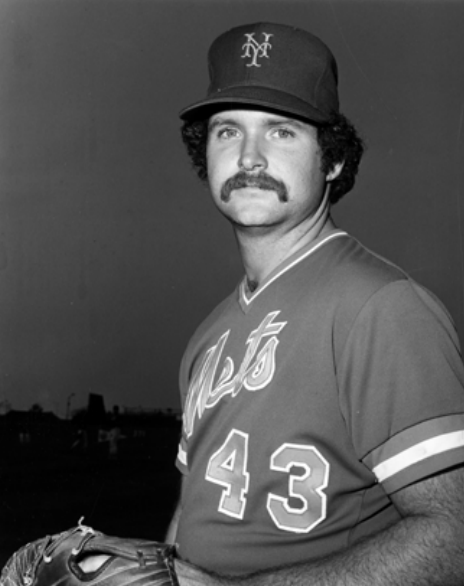

Terry Leach

Terry Leach had an unusual delivery, took an abnormally long and circuitous route to the major leagues, eventually found uncommon success, and recounted it all in a book entitled Things Happen for a Reason.

Terry Leach had an unusual delivery, took an abnormally long and circuitous route to the major leagues, eventually found uncommon success, and recounted it all in a book entitled Things Happen for a Reason.

There were in fact lots of reasons for the things that happened during Leach’s unique baseball career, which spanned 18 professional seasons—one in independent ball—among seven organizations including two that employed him twice. Leach was traded three times, released four times, spent at least part of all but six years in the minor leagues, and didn’t make an Opening Day roster until he was 33 years old. Along the way he authored one of the most stunning single-game pitching performances in the history of the New York Mets; shocked the baseball world while racing to a 10-0 start in 1987; and served a key role in the bullpen for the 1991 World Series champion Minnesota Twins.

Terry Hester Leach was born on March 13, 1954 in Selma, Alabama, the youngest of Alma and Cecil Leach’s three boys. Cecil, a cotton buyer, was a one-time football player at Auburn University and his boys—Billy, 14 years older than Terry, and Alan, seven years Terry’s senior—were each good athletes, so young Terry had to work hard to keep up with his siblings. “Being younger pushed me to being a little bit better,” Terry wrote in his book. “Being at a disadvantage can work for you if you take your failures and learn from them.”1

Leach played baseball for Selma High and for a Dixie Senior League team that finished as the runner-up in the 1969 Dixie World Series and was its champion in 1971. After high school graduation in 1972 he was offered a partial baseball scholarship to Auburn, where he began as a third baseman before being converted to a pitcher.

Listed as 6-feet and 215 pounds, Leach was a stocky, hard-throwing right-handed pitcher whose success at Auburn earned him a draft pick by the Boston Red Sox in the January 1976 supplemental draft, but the pick was voided when Leach was ruled ineligible due to his age. His shot at getting drafted a second time vanished when he injured his elbow pitching for Auburn that spring.

Leach said the injury—which he later surmised was a torn collateral ligament—forced him to abandon a previous focus on mid-90s fastballs, expand his repertoire, and learn to retire batters with finesse rather than fire. Undrafted and still overcoming the injury, Leach latched on briefly with the Baton Rouge Cougars of the independent Gulf States League in 1976, and impressed Atlanta Braves scouts enough at an open tryout the following spring to get an assignment with their Greenwood team in the Class-A Western Carolinas League.

Leach credited his pitching coach in Greenwood, Kenny Rowe, a middle reliever with the Dodgers and Orioles in the 1960s, with suggesting that he try throwing side-arm in attempt to get more movement on his pitches, and Leach said the change brought immediate and dramatic results. “With my new way of coming at hitters from down under, pitching for me suddenly stopped being a matter of blowing people out with my power and became a matter of finessing with my movement,” Leach wrote. “When I’d thrown overhand and hard I’d had to beat people up, overpower them. Now I adopted a completely different approach. … I was a whole new pitcher.”2

Leach in coming years would refine the style, developing a distinctive delivery that featured a full side-arm whip released close to the ground, his right knee trailing behind in the dirt. The action provided good sink to his two-seam fastball and a rising effect to his slider, even as his velocity rarely exceeded the low 80s. When he was going well, Leach got his share of strikeouts, but he excelled at keeping hitters from making hard contact, often inducing groundballs and rarely allowing home runs—just 38 in 700 innings pitched in the big leagues.

Leach in coming years would refine the style, developing a distinctive delivery that featured a full side-arm whip released close to the ground, his right knee trailing behind in the dirt. The action provided good sink to his two-seam fastball and a rising effect to his slider, even as his velocity rarely exceeded the low 80s. When he was going well, Leach got his share of strikeouts, but he excelled at keeping hitters from making hard contact, often inducing groundballs and rarely allowing home runs—just 38 in 700 innings pitched in the big leagues.

Buoyed by the new approach, Leach, 23, struck out 67 batters in 67 innings for Greenwood in 1977, and was on his way up in the Braves organization.

Leach split 1978 between Kinston of the Class-A Carolina League and Savannah of the Double-A Southern League, going a combined 6-4, with a 3.76 ERA in 43 games including two starts. Pitching to a 1.96 ERA in 40 relief appearances for Savannah in 1979, he earned a promotion to Triple-A Richmond where he posted a 1.93 ERA in seven games including two starts.

Leach was pitching well in Savannah again in 1980 (5-1, 3.21, mostly in relief) when he was released in midseason, saying in his book that his advanced age for that level (26) and status as an undrafted player made him expendable in the eyes of the Atlanta organization. Days later he was picked up by the Mets, who had a vacancy for a starting pitcher with their Jackson club of the Double-A Texas League, and Leach finished the year there with a 5-1 record and a 1.50 ERA, ranking second in the league.

Beginning a lengthy turnaround, and hungry for talent at the top level, the Mets proved to be a good place for a determined minor leaguer to land. Leach within a year would make his major-league debut after going a combined 10-3 in stops with Jackson and Tidewater of the Triple-A International League. He made his major-league debut on August 12, 1981. Pitching in relief of Ed Lynch at Wrigley Field, Leach had a rough inning, surrendering three hits including a two-run home run by the Chicago Cubs’ Mike Lum over the ivy in right field. The outing cost Lynch a win, but the Mets rallied to win the game.

Leach got a no-decision in his next appearance, a start against the Philadelphia Phillies at Shea Stadium, and finished the season with a 1-1 record and a respectable 2.55 ERA in 21 appearances.

Leach split 1982 between Tidewater and the Mets, exclusively in relief except for one spot start, but that was a memorable one. Called on when scheduled starter Rick Ownbey was sidelined with a blister on the season’s final weekend, Leach fired a 10-inning, complete-game, 1-0 victory in Philadelphia, surrendering five walks and a single hit—a fifth-inning triple by Luis Aguayo, becoming the first Mets player to throw a one-hitter since Tom Seaver in 1977. Leach described having an unusually active slider that night—including one that broke between the legs of Philadelphia’s Ozzie Virgil. Pete Rose, who went 0-for-4 with a strikeout in the game, in an 1984 interview listed Leach among the toughest pitching opponents he faced.3 Rose was 2-for-9 in his career against Leach.

Leach’s performance —which bettered nine innings of scoreless, one-hit ball by his counterpart, John Denny of the Phillies—wasn’t the only unusual aspect of that memorable game: Due to a luggage mixup at the airport, the umpiring crew dressed in spare Phillies uniforms and groundskeepers’ gear.

As spectacular as the one-hitter was, it was more than two years—and two trades—before Leach resurfaced in the big leagues. He spent all of 1983 in Tidewater, going 5-7 in a swingman role and helping the club to victory in the Triple-A World Series. Leach said his performance in that event attracted the attention of the Chicago Cubs, who shortly afterward traded prospects Jim Adamczak and Mitch Cook to the Mets for him.

A subsequent Cubs managerial change, to Jim Frey for the 1984 campaign, made for a short stay in Chicago. Concerned that Leach’s style made him vulnerable to left-handed hitters—borne out in career splits showing lefties hit .294 off Leach with a .409 slugging percentage, while right-handers combined for a respective .233 and .323—Frey insisted that Leach change his pitching style, but Leach was uncomfortable with the switch, fell out of favor, and was swapped to Atlanta for pitcher Ron Meredith in early April.

The second stint with the Braves ended just how the first one did, with a midseason release from Triple-A Richmond and subsequent re-signing by the Mets. Assigned again to Tidewater, Leach went 11-3, with a 3.34 ERA in 43 relief appearances for the Tides.

Spending 1985 in Tidewater, Leach was dominant in relief, posting a 1.59 ERA and a 0.90 WHIP before being recalled to the Mets in June. In 22 games he posted a 2.91 ERA, and was even better in four spot starts, going 3-1 with a 2.70 ERA. Davey Johnson, who had managed Leach in Tidewater in 1983 and now managed the Mets, liked his versatility, desire to pitch, and what he considered a “rubber arm.” Teammates took to calling Leach “Jack” as in “Jack of all trades.”4

“He just wants the ball,” Johnson said of Leach. “He doesn’t want to give it up when he’s on the hill, and if he’s not on the hill he can’t wait to get there. Fact is, if you tell him to get warm, he may call down and tell you he’s ready after three pitches, he wants to be in the game so bad.”5

The Mets, who won 98 games in 1985 but finished just short of St. Louis for the National League East crown that year, fielded a dominant, 108-win team in 1986 that had no room for the 32-year-old Leach, who was invited to camp as a nonroster player and spent all but five weeks of the year in Tidewater. Although expecting a call-up when rosters expanded in September, Leach missed his chance after dislocating his shoulder in a home-plate collision in a late-season Tidewater game. Leach, as it turned out, would be one of four members of that World Series-winning Mets team not to be awarded a ring—although the Mets relented years later when, under pressure from Randy Myers, co-owner Fred Wilpon agreed to split the cost with Myers.

Leach was again assigned to minor-league camp late in spring training in 1987, and the normally easygoing Southerner made a show of his disappointment with the news, slamming the door on his way out of Johnson’s office. But fate intervened, when Dwight Gooden checked into drug rehab and reliever Roger McDowell went to the disabled list just before Opening Day, providing the 33-year-old Leach with his first Opening Day major-league assignment. “I hated to get a job this way, but that’s why they keep me around,” Leach surmised at the time. “I’m an insurance policy in case someone gets hurt.”6

Although the Mets failed to defend their title in 1987—with all five of their vaunted starting pitchers missing at least part of the year due to injury—the disarray proved to be just the opportunity Leach needed.

After 18 games in relief, Leach was tabbed to start for the first time on June 1 when Rick Aguilera went down with an injury. Leach that day bested Fernando Valenzuela, 5-2, at Dodger Stadium. He got a no decision against the Cubs eight days later then started a remarkable run of six wins and two no-decisions in eight consecutive starts, allowing two earned runs or less in six of them, and running his record to 10-0 by August 11—still the Mets record for an unbeaten start to a season.

Fans that summer campaigned to get Leach named to the National League All-Star team—however, Johnson, as the NL manager, declined. But Leach’s sizzling streak helped the battered Mets, struggling at .500 in June, to roar back into the National League East race. Leach’s streak ended with a loss to Chicago on August 15, and when David Cone returned from the disabled list later that month, Leach returned to the bullpen. His 11th win that year came in relief over the Phillies on September 8. Leach finished 11-1 with a 3.22 ERA.

Lynch had knee surgery after the 1987 season, but for the first time in 1988 had a role all but assured. Spending the entire season in New York, Leach went 7-2 with a 2.54 ERA in 52 games and 92 innings pitched for the National League East champions. He appeared three times in the NLCS against Los Angeles, pitching five scoreless innings, as the Mets lost the series in seven games.

Leach began the 1989 season in New York but was traded to Kansas City in June, to make room for 24-year-old prospect David West, promoted from Tidewater and inserted into middle relief. The trade—bringing back prospect Aguedo Vasquez after the season —was the first of several that eventually disassembled the once-mighty Mets. McDowell, Aguilera, Mookie Wilson, and Lenny Dykstra were all gone before the 1989 season was complete.

Leach, who went 5-6 with a 4.15 ERA in Kansas City in 1989, returned to the club the following spring only to suffer a familiar disappointment — a release just before Opening Day. He quickly caught on with the Minnesota Twins, however, and spent two productive years in the Twins bullpen, pitching in 55 games in 1990 (3-5 with a 3.20 ERA) and 51 in 1991 (1-2, 3.61), when the Twins surprised baseball with a World Series championship. Leach pitched twice during the World Series, surrendering one run in 2⅓ innings. He secured a key out in Game Three in Atlanta, striking out left-handed-hitting Mark Lemke with the bases loaded. “I was tempted to ask T.K. [Twins manager Tom Kelly], ‘Do you know what you are doing here, Tom? You’re bringing in a side-armer against a left-hander. You never do that,’” Leach recounted.7

The Twins gave Leach a ring, but did not elect to offer him a new contract. Leach subsequently signed a deal with Montreal for 1992, only to see the Expos release him just prior to Opening Day.

Undaunted, the 38-year-old Leach resurfaced with the Chicago White Sox and, thanks to adding a new wrinkle to his slider and mixing in a changeup, turned in a fine year in relief, going 6-5 with a 1.95 ERA over 73⅔ innings—the best ERA of his career. He returned in 1993 only to encounter elbow trouble, and got into just 14 games between lengthy rehab stints in the minors. He eventually saw elbow surgeon James Andrews, who discovered extensive damage to his elbow. Leach attended training camp with the White Sox in 1993 and the Tigers in 1994 and 1995 but didn’t make any of those clubs, and reluctantly retired to Florida, where among other things, he penned his memoirs.

Co-written with Tom Clark, the American poet who also wrote several books on baseball, Things Happen for a Reason: The True Story of an Itinerant Life in Baseball was published by Frog Ltd. in 2000 and highlighted Leach’s folksy Southern charm and skill as a storyteller. In it he cheerfully and at times wistfully recounts a hard life on the road as a minor-league survivor, the pursuit of cheap food and cold beer with teammates, how his met his wife, the former Chris McCowan, in Savannah, and later named their daughter after the city, all while gently whipping a few hard sliders past a myopic baseball world that so often failed him.

“The fact that Things Happen for a Reason is a classic baseball book shouldn’t obscure that fact that it is also a gorgeous piece of pure writing, of human language got onto the page,” author Jonathan Lethem wrote in a blurb published on the back cover.

Leach finished his career with a 38-27 lifetime record, with 10 saves, pitching 700 innings in 376 games.

“Baseball’s a frustrating game at times, other times it’s exciting, and then again strange, even kind of deep,” he wrote. “Spending your life in it, you’ll find insecurity, confusion, joy, boredom, friendship, mistrust, surprise, despair, hope and pain. So much happens—you just have to be conscious of the fact that you’re not in control of any of it, and from that point it does make sense, in a funny kind of way.”8

Sources

In addition to the works cited in the Notes, the author consulted the following:

Ultimatemets.com.

Baseballreference.com.

scouts.baseballhall.org.

studiousmetsimus.blogspot.com.

uni-watch.com.

Notes

1 Terry Leach with Tom Clark, Things Happen for a Reason: The True Story of an Itinerant Life in Baseball (Berkeley, California: Frog, Ltd., 2000).

2 Leach with Clark.

3 Richard Grossinger, The New York Mets: Ethnography, Myth, and Subtext (Berkeley, California: Frog Ltd., 2007).

4 Leach with Clark.

5 Davey Johnson and Peter Golenbock, Bats (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1986).

6 Jack Lang, “Mets’ Terry Leach (5-0) Just Don’t Get No Respect,” The Sporting News, June 29, 1987.

7 Leach with Clark.

8 Leach with Clark.

Full Name

Terry Hester Leach

Born

March 13, 1954 at Selma, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.