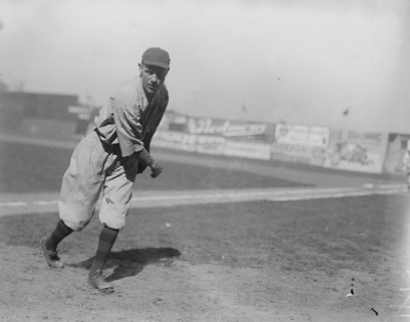

Tom Hughes

When one examines the Miracle Braves’ performance it is obvious that the bulk of the pitching effort rested with just three men: Dick Rudolph, Bill James, and George Tyler. Starting 107 of the 158 games the team played, they won 68 of the Braves’ 94 victories. Yet, when Boston clinched the pennant against the Chicago Cubs, it was neither Rudolph, James, nor Tyler who won the game. It was “Salida Tom” Hughes, recalled from the minors just weeks earlier.1 Hughes’ recognition as Salida Tom is important in that five men named Tom Hughes played in the major leagues. Four were pitchers, including Long Tom Hughes, a contemporary of Salida Tom. Their respective exploits on the mound were then – and still are – confused with each other’s.

When one examines the Miracle Braves’ performance it is obvious that the bulk of the pitching effort rested with just three men: Dick Rudolph, Bill James, and George Tyler. Starting 107 of the 158 games the team played, they won 68 of the Braves’ 94 victories. Yet, when Boston clinched the pennant against the Chicago Cubs, it was neither Rudolph, James, nor Tyler who won the game. It was “Salida Tom” Hughes, recalled from the minors just weeks earlier.1 Hughes’ recognition as Salida Tom is important in that five men named Tom Hughes played in the major leagues. Four were pitchers, including Long Tom Hughes, a contemporary of Salida Tom. Their respective exploits on the mound were then – and still are – confused with each other’s.

Although overshadowed by Rudolph, James, and Tyler in 1914, Hughes proved a mainstay of the Braves staff the next two seasons, showing ability as both a starter and reliever. His time with the Braves represented his second stint in the majors; he had pitched for the New York Highlanders from 1906 through 1910 with middling success.

Thomas L. Hughes was born at Coal Creek, Colorado, on January 28, 1884. He was the youngest of five children. His parents, Richard and Kelzia Hughes, had emigrated from Wales. The 1880 US Census listed Richard as a miner, later a locomotive engineer.2 The family moved frequently, possibly because the father’s work on the railroad. In 1900 the Hughes family was living in Trenton City, Missouri, which contained a Rock Island Railroad facility; ten years later they had moved to the railroad town of Salida, Colorado, and it is from there that the pitcher’s moniker stemmed.

According to Baseball Magazine, young Hughes was working in a railroad repair shop as a blacksmith when he was contacted to play professional baseball. The article indicated that he was living in Salida at the time, but it seems more likely that Hughes resided in Missouri with his parents, because he began play in the Missouri Valley League, which consisted of teams from Missouri and eastern Kansas, considerably distant from Colorado.3

During his first season, 1904, Hughes pitched for the Pittsburg Coal Diggers and Topeka Saints, posting a combined 10-26 record.4 In 1905, with the Topeka White Sox of the Western Association, he improved to 14-18. Sensing potential, the New York Highlanders drafted him and sent him to Atlanta of the Southern Association for seasoning. In 1906 Hughes had a breakout season with the Atlanta Crackers, finishing with a 25-5 record. His performance earned a call-up to New York in September.

Hughes made his major-league debut against the St. Louis Browns on September 18. Eleven days later he earned his first big-league win, a complete-game 5-4 effort over the Boston Americans. Hughes spent most of the next two seasons back in the minor leagues, initially with Montreal and then Newark in the Eastern League, fashioning successive 14-17 and 16-9 records. Significantly, as it would turn out later, his manager at Newark was George Stallings. Called up to the Highlanders again at the end of 1907, Hughes appeared in four games, winning twice.

In 1909 Hughes became a member of the Highlanders’ starting rotation. Appearing in 26 games, starting 15, he finished with a 7-8 record for the fifth-place New York club. While earned-run averages did not become an official statistic until 1913, subsequent research found that Hughes’s ERA for 1909 was 2.65. This seems an impressive figure by today’s standards; in truth, it was just average, worse than the league average ERA of 2.47.

The Highlanders vaulted from fifth to second place in 1910. Despite their improvement, not all was well within the organization. Manager Stallings resigned during the closing weeks of the season after first baseman Hal Chase continually second-guessed his managerial decisions – with team owners William Devery and Frank Farrell not backing Stallings. Stallings went on to manage the Buffalo Bisons in the International League for two years while Hughes pitched for the rival Rochester Bronchos (later Hustlers). In 1914 they reunited when Stallings became manager of the Braves, playing a key role in resurrecting Hughes’s major-league career.5

Hughes’s performance in 1910 was mediocre. Finishing at 7-9, he was the least effective of the regular starters. He did, however, show flashes of excellence. On August 30 against the Cleveland Naps, Hughes threw 9 1/3 innings of no-hit ball in a scoreless tie before being touched for two hits in the tenth, then surrendered a barrage of hits and runs in the 11th, losing 5-0. Adding insult to injury, several news reports of the game, including that in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, identified Hughes as Long Tom Hughes. This was one of several examples where the simultaneous careers and accomplishments of Salida Tom and Long Tom were confused.6 Although a solid effort, Hughes’s performance against the Naps seemed to confirm his reputation as one who weakened in the late innings. That he could not go the distance proved detrimental to his career with the Highlanders after the season ended.7

In January 1911 the Highlanders sold Hughes’s’ contract to Rochester of the Eastern League. Press reports noted his reputation as a “hard luck” pitcher who pitched well but would then be “touched up for a few hits in a bunch, and lose his game.”8

While professional disappointment occurred, personal happiness abounded. On March 11, 1911, Hughes married a neighbor, Esther Lee Wilson; the 1910 census shows the Hughes and Wilson families living on the same block. She had been supporting her widowed mother and sister through employment as a bookkeeper and stenographer at the local Red Cross Hospital. After their marriage, Hughes moved into the Wilson residence.9

The wedding took place in Denver; the bride’s mother and uncle accompanied her to the ceremony. Hughes was described as “an old Salida boy” and “exceedingly popular locally.” The “old Salida Boy” description was something of a stretch; Hughes had lived in Salida something less than ten years. The couple left the day after the ceremony for Anniston, Alabama, where Hughes began spring training. Their marriage lasted 50 years, until Hughes’s death in 1961.10

For the next four seasons, 1911-1914, Hughes pitched for Rochester. He kept in contact with former teammates from the majors. In 1913, prior to the beginning of spring training, Salida’s Mountain Mail reported that Russ Ford, a pitcher for the Highlanders, had visited Hughes in Denver, where Hughes served as enrollment clerk for Colorado’s House of Representatives.11 Hughes, apparently an enterprising sort, also owned a “gent’s furnishing store” in Salida at about the same time.12

The Rochester Bronchos of the Eastern League (later the International League) were at the highest level of minor-league play. Hughes pitched well, averaging 16 wins per year for a team that regularly finished in the first division and won the league championship in 1912. In 1914 he led the league with 182 strikeouts; his solid performance led to his purchase by the Braves on September 5, 1914.13

George Stallings was then manager of the Braves. Stallings had witnessed his performance with the Highlanders and with Rochester. And Fred Mitchell, who essentially served as Stallings’ pitching coach on the Braves, coached with Stallings on the Highlanders, then played with Hughes at Rochester in 1911. The day Hughes was purchased, the Braves were in a first-place tie with the Giants; they finished winning 27 of 34 games to sweep past New York. Hughes contributed two victories to the late-season run; his first, a complete-game 3-2 effort on September 29 against Chicago, clinched the pennant for the Braves.

It was the Braves’ first championship since the old Beaneaters took the title in 1898. Hughes won again on October 5 against Brooklyn as Stallings was clearly resting James, Rudolph, and Tyler for the World Series against the Philadelphia A’s. Even though Hughes came to the Braves late in the season, the team’s victory brought him acclaim in hometown Salida. Salida’s Mountain Mail noted, “Mr. Hughes grew up in this city, spends his winters here and has a multitude of friends who take delight in his success and who would like to see him have a chance in the World Series. His friends here have great confidence in him.”14

Hughes did not appear in the World Series, as the Braves dispatched the A’s in four straight games. Joining the team late, he was not eligible to receive $2,812 in World Series winning player shares.15 His late-season performance, however, gained him a place with the Braves for the next season.

The Braves’ efforts to defend their world championship proved unsuccessful in 1915; they finished second to the Philadelphia Phillies. Pitching proved the major culprit in denying a second straight title. Although Rudolph won 22 games, James and Tyler both fell off their pennant-winning efforts, the illness-plagued James especially, as he dropped from 26-7 to 5-4. This created an opportunity for Hughes, who responded with 16 wins. Pitching in a league-leading 50 games, he started 25 and sported a 2.12 ERA, fifth in the senior circuit. Hughes led the league with nine saves, (a statistic not recorded or recognized at the time). His double-duty performance that year was rare. As of 2012, Hughes was one of only 17 pitchers to have started 20 or more games and finished 20 or more games in relief in a season.16

In 1916 Hughes posted a 16-3 record, leading the National League in winning percentage (842.). On June 16 he threw the second no-hitter of his career when he blanked Pittsburgh 2-0. The game ended with a flourish, Hughes recording the final out by fanning Honus Wagner.17

With his effort against Cleveland in 1910 recognized as a no-hitter at the time, Hughes became only the second pitcher besides Cy Young to throw a hitless games in both the American and National Leagues. His record-setting efforts did not stop with the no-hitter. A week after his hitless gem, he entered a game in relief against Philadelphia, and held the Phillies hitless for 3 1/3 innings before allowing a hit that ended a streak of 15 1/3 hitless innings over four games including the no-hitter. At least one newspaper called this a record,18 but another quickly noted that it had fallen short of a record set in 1904 by Cy Young.19 Nevertheless, Hughes’s pitching was superlative. Misfortune struck later in his season, which ended when a pitch from Phillies pitcher Erskine Mayer struck his wrist and broke it on September 7.

There are different accounts of what happened to Hughes in 1917. The Sporting News wrote that he was a holdout during spring training.20 Hughes must have come to an agreement quickly, because in mid-March he was mentioned by the Boston Globe as pitching a practice game, his first appearance since his wrist was broken. “He worked … only three innings, but feels no ill effects from the injury,” the Globe wrote.21 But two weeks later he was reported to have a sore arm.22 Harold Kaese’s history of the Boston Braves states that Hughes was out of action because of a sore hand.23 Based on subsequent events, Hughes it was probably a sore arm. Whatever the cause, Hughes was out of action until midseason. When he returned, he appeared in just 11 games, starting eight and fashioning a 5-3 record with a 1.95 ERA.

Hughes was unable to pitch for most of 1918; he appeared in just three games. On April 19 he pitched a complete game against the Phillies, losing in the tenth, 4-3, despite hitting a solo home run in the seventh himself. It was reminiscent of his losing no-hit effort against Cleveland eight years earlier. Eight innings of relief against the Phillies five days later, again in a losing effort, and a single inning in relief against St. Louis on July 17 were his last appearances in the major leagues.

For his major-league career, Hughes showed a 56-39 record with a 2.56 ERA, slightly better than the major-league average during the years he pitched (2.68). A more recently developed tool suggests his effectiveness with the Braves. His WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) was 1.022, the best in Braves franchise history for those who pitched 300 innings or more.24 He was extremely effective at the height of an abbreviated major-league career.

Hughes’s days of playing professional baseball were not quite done. In July 1919 the Los Angeles Times noted that Johnny Powers, owner of the Los Angeles Angels in the Pacific Coast League, had offered Hughes a tryout, noting that he had the potential to start or relieve. Within days, the tryout apparently successful, Hughes signed a contract. He believed he had overcome “a cold in his arm” which caused his release from the Braves.25 On July 19 he started against the Vernon Tigers and pitched shutout ball until the fifth inning, when his arm went dead. In dramatic fashion, the Times’s Harry Williams, reporting on the game wrote, “Two months of faithful preparation, more months of careful nursing of the old wing to bring it back to life went for naught, and the hope of all this was shattered when the arm dropped limp at his side. Tom Hughes had failed to come back.26

Soon after, the New York Times reported that Hughes had quit for good after “one disastrous trial on the mound.”27 The Los Angeles Times subsequently reported that Hughes “whose attempt to come back with the Angels failed,” was now a used-car salesman.28

But Hughes had seven more years of pitching left. In 1920 he asked Powers for another tryout and was successful. In what was left of the 1920 season, Hughes made an effective comeback, going 7-4 for the Angels. Any doubts that his arm had returned to form were erased in a game against the San Francisco Seals on September 26; he pitched all 15 innings to win a 3-2 decision. Unlike the dark description of his setback the year before, Hughes’s effort was described in colorful euphemisms of early 20th century sports reporting: “And above all the hectic disturbance, glimmering like a comet at midnight, shone the name of Tom Hughes, whose rejuvenation as a pitcher is undoubtedly the most phenomenal comeback in the history of the game.”29

Hughes went on to pitch for the Angeles through 1925. During that time he won 70 and lost 61, serving as a coach and temporary manager on occasion.30 The old man of the team, he treated his teammates to cigars when his only child, Thomas Jr., was born on April 28, 1925. That season was his last with Los Angeles.

In 1926 Hughes split his time between Little Rock of the Southern Association and Beaumont and San Antonio of the Texas League, compiling a 5-12 record with a 4.60 ERA. By then he was 42 years old and it was time to retire. Hughes had proved that he could come back from the arm ailment that ended his major-league career. After retiring from baseball, Hughes worked in the insurance business, then during World War II in the production of airplanes.31 His son, Thomas Jr. graduated from the United States Naval Academy and served three years on active duty. After the war, young Hughes established himself as an executive in the insurance industry. In 1955 he died at the age of 29 in an auto accident on the Hollywood Freeway.32

Six years later, on November 1, 1961, Salida Tom died, succumbing to the combined effects of pneumonia, emphysema, and tuberculosis, a disease he had contacted 11 years earlier. Burial was at Forest Lawn Memorial Park alongside Thomas Jr.33 At the time of Hughes’ death, he was widely described as one of a few pitchers who had thrown no-hitters in the American and National League,34 but this was before the retroactive canceling of his effort against the Cleveland Naps.

Researching Hughes’s life and career reveals little of his personality. In a day when player interviews were rare, few quotes attributable to Hughes could be found. Thus, he appears through the lens of time as a one-dimensional individual – except for one incident hinting at his strength of character, as described in a short article in his file at the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Dated October 7, no year given, the article tells of a horse-drawn carriage occupied by two young women that went out of control. Hughes, hearing their screams, ran into the street and grabbed the horse’s bit strap. The animal reared and dragged Hughes several feet before stopping. The article observed that Hughes “probably saved the young women from serious injuries.” 35 At that one instant, Salida Tom proved he could do more than pitch.

(As of this writing, the statistics for Salida Tom’s post-major-league career have been mistakenly placed in the minor-league record of Long Tom Hughes in baseball-reference.com. Efforts were being made to correct this. In addition, many newspaper articles over the years have confused the two men.36)

This biography is included in “The Miracle Braves of 1914: Boston’s Original Worst-to-First World Series Champions” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 This article is immeasurably better thanks to the assistance of Dr. Arlene Shovald of Salida, Colorado, whose research generated a great deal of information about Hughes. Dr. Shovald provided all notes referring to The Mountain Mail, Salida’s newspaper. Barbara Erion’s knowledge of Ancestry.com yielded knowledge of the Hughes family, especially his wife and son.

2 Data on the Hughes family obtained from Ancestry.com.

3 Ward Mason, “Vote for Hughes,” Baseball Magazine, November 1916, 40. The article is vague about who the person was who enticed Hughes into professional baseball.

4 All baseball statistics except as described in Note 42 are from baseball-reference.com/players/h/hugheto02.shtml or Retrosheet.

5 Bill James, The Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers From 1870 to Today (New York: Scribner, 1997), 45; Ed Fitzgerald, ed., The American League (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1959), 8.

6 From various Cleveland and New York newspaper clippings in the Tom Hughes file at the Baseball Hall of Fame, September 1910.

7 Under guidelines then governing, Hughes received credit for a no-hitter. It was a feat recognized for more than 80 years until the Major League Committee for Statistical Accuracy redefined a no-hitter in 1991 as one in which “a pitcher (or pitchers) allows no hits during the entire course of a game, which consists of at least nine innings.”

8 Three Yankees Sold,” New York Times, January 4, 1911, 11.

9 1913-1914 Salida City Directory; email from Dr. Arlene Shovald, February 16, 2013.

10 “Hughes-Wilson Nuptials,” The Mountain Mail, Salida, Colorado, March 10, 1911; “Former Salidian Esther W. Hughes Dies in California,” The Mountain Mail, June 26, 1967.

11 “100 Years Ago,” The Mountain Mail, Salida, Colorado, February 5, 2013, 11.

12 Mason, Baseball Magazine, 40.

14 “Salida Boy Wins National Baseball Fame,” The Mountain Mail, Salida, Colorado, October 1914, 11.

15 Mason, Baseball Magazine, 40.

16 http://highheatstats.blogspot.com/2011/11/10-gs10-gf-not-for-anyone-2011.html.

17 “Tom Hughes Pitches No-Hit, No-Run Game, Boston Daily Globe, June 17, 1916, 7.

18 “Tom Hughes Makes New Baseball Record, Hartford Courant, June 25, 1916, Z6.

19 “Young in 23 Hitless Innings; Pitching Record for Majors,” Washington Post, July 16, 1916, S2.

20 “Braves Look in Mirror and See Team to Head Off Giants,” The Sporting News, March 15, 1917, 1.

21 “Stallings Acts as Drillmaster” Boston Daily Globe, March 15, 1917, 7.

22 “Yankees Get Rest,” New York Times, April 2, 1917.

23 Harold Kaese, The Boston Braves, 1871-1953 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004), 179.

24 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tom_L._Hughes.

25 “Baseball Notes,” Los Angeles Times July 10, 1919, III2; “Morley Signs Up Tom Hughes,” Los Angeles Times, July 14, 1919, 15.

26 “Tigers Down Angels Again”, Los Angeles Times, July 20, 1919, 18.

27 “Hughes Leaves Baseball,’’ New York Times, August 6, 1919, 16.

28 “Baseball Notes,” Los Angeles Times, October 16, 1919, III1.

29 “Wonder Where Tom Hughes Got the Goat Glands,” Los Angeles Times, September 27, 1920, 16.

30 “Seraphs Knuckle to Work,” Los Angeles Times, March 1, 1923, III2.

31 “Thomas Hughes, former Salidian, Dies in California,” The Mountain Mail, Salida, Colorado, November 2, 1961.

32 “Ex-Baseball Star’s Son Dies in Crash, Los Angeles Times, March 10, 1955, 5.

33 “Thomas Hughes, former Salidian, Dies in California,” The Mountain Mail, Salida, Colorado, February 5, 2013, 11.

34 “Obituary,” The Sporting News, November 8, 1961, 24.

35 Hughes file, Baseball Hall of Fame.

36 Statistical data for Salida Tom Hughes’s performance in the Pacific Coast League is contained in Dennis Snelling, The Pacific Coast League: A Statistical History, 1903-1956 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1995), 271. Baseball-reference.com/players/h/hugheto02.shtml mistakenly attributes Hughes’s PCL statistics to Long Tom Hughes. The latter had been retired from the game by then. Numerous references to Salida Tom Hughes in the Los Angeles Times mention prior experience with the Braves, a team Long Tom never played for. An article referring to the birth of Salida Tom’s son, Thomas Jr., in the Los Angeles Times identifies the birthdate of Tom Jr. as April 28, 1925, the date that is on an application for a headstone signed by Mrs. Thomas Hughes dated April 6, 1955. An email from Bob Hoie to the author on February 9, 2013, contains further detail that Salida Tom pitched for the Angels in the 1920s. Long Tom Hughes did pitch for the Angels, but in 1914 and 1915.

Full Name

Thomas L. Hughes

Born

January 28, 1884 at Coal Creek, CO (USA)

Died

November 1, 1961 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.