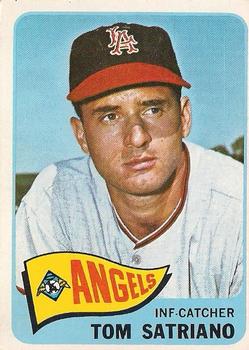

Tom Satriano

In 1966, The Sporting News quipped that “Tom Satriano has more gloves than [his wife] . . . not many husbands can make that statement.”1 “[N]o threat to [Olympic sprinter] Bob Hayes, or even [actress] Helen Hayes,” the slow-footed Satriano constructed a 10-year major league career with his adaptability at catcher and every infield position. “I realize that my versatility has kept me in the majors,” he admitted in 1967. “I also believe that it’s made me more alert than the average player.”2

In 1966, The Sporting News quipped that “Tom Satriano has more gloves than [his wife] . . . not many husbands can make that statement.”1 “[N]o threat to [Olympic sprinter] Bob Hayes, or even [actress] Helen Hayes,” the slow-footed Satriano constructed a 10-year major league career with his adaptability at catcher and every infield position. “I realize that my versatility has kept me in the majors,” he admitted in 1967. “I also believe that it’s made me more alert than the average player.”2

Thomas Victor Nicholas Satriano was born on August 28, 1940 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the youngest of two sons of Victor Nicholas and Teresa Edith (Mussano) Satriano.. He was the grandson of Italian immigrants Emilio and Giovanna Satriano who arrived in the Steel City with their baby daughter around the turn of the 20th century. Tom’s father was born shortly thereafter. In the 1930s, Victor married Teresa and supported his growing family by selling life insurance. The family moved to California during or shortly after World War II.

The boys attended Loyola High School, a Jesuit school two miles west of downtown Los Angeles, where Tom established his credentials as a pitcher and shortstop in prep school competition. In May 1958, a month before his high school graduation, he was tabbed alongside future major leaguers Chris Krug and Larry Maxie as “Southern California prep ‘phenoms’ [destined to receive] some spirited bidding” from major league clubs.3 Though Krug and Maxie signed with the St. Louis Cardinals and Milwaukee Braves, respectively, Satriano set a course for the University of Southern California. Before his first inning of play with USC, for the first of two consecutive summers, he joined his future Trojan teammates in Canada’s Alberta province playing for the Edmonton Eskimos in the Western Canada Baseball League.

During his collegiate career, Satriano alternated between third base and shortstop. In 1960, while leading USC to the College World Series, the left-handed hitter was selected as an All American third baseman. The next year he established an NCAA record with 10 hits in a five-game title match while helping lead USC to a national championship. Once again attracting major league scouts, Satriano was offered bonuses topping $75,000 from the Los Angeles Dodgers and Cincinnati Reds, both of which sought to convert the strong-armed infielder to catcher. Unwilling to move behind the plate, in July 1961 the college junior inked the expansion Los Angeles Angels’ first bonus contract with scout Ross Gilhousen for $50,000. Though smaller than other offers, the sum still qualified under the bonus rules, and the Angels were forced to place Satriano on the active roster.

On July 23, 1961, Satriano made his major-league debut in Los Angeles’s Wrigley Field against the Washington Senators. Pinch-hitting for pitcher Ted Bowsfield in the sixth, he grounded out to second baseman Chuck Cottier. Three weeks later, after three additional appearances as a pinch hitter or runner, Satriano got his first start as the Angels third baseman in a game against the Cleveland Indians. Following a sixth inning leadoff walk Satriano stole second and scored on a RBI single by first baseman Steve Bilko. He was also flawless in the field with one putout and three assists including initiating a 5-4-3 double play to end the fifth inning. The next day, August 12, Satriano got his first major league hit, a 400-foot ninth inning two-run homer to right field against Indians righthander Mudcat Grant to cap the scoring in the Angels 3-0 win.4

Except for two hits against the Boston Red Sox on August 25, Satriano went hitless in his next 20 at-bats. In September, he hit safely in nine of 10 games but struggled to keep his average above .200. These difficulties affected his defense:, Satriano committed errors in four consecutive September appearances when shifting between second and third base. He finished the season with two stolen bases (he wouldn’t swipe another for more than three years) and a .198/.294/.302 line in 96 at-bats. Despite the meager numbers The Sporting News tabbed the youngster, alternately nicknamed “Satch” or “Tommy Trojan,” as a “can’t miss” prospect, whose “poise and sureness” had impressed opponents.5 But on November 27, in a move apparently hedging their bets, the Angels picked up veteran minor league third baseman Felix Torres from the Philadelphia Phillies in the rule 5 draft.

In 1962, competition for the Angels starting third base job was a scramble between Satriano, Torres, and three others. Torres, who was the only Angels player slower than Satriano, won the job. Angels manager Bill Rigney briefly considered moving Satriano to second base before the youngster’s offensive challenges resurfaced. A week before the start of the regular season, with the bonus rules relaxed, Satriano was assigned to the Triple-A Hawaii Islanders in the Pacific Coast League. Splitting his time between third and shortstop, he got off to a fast start—15 hits in his first 43 at-bats—and by late May was leading the circuit in RBIs. On July 15, Satriano had a perfect 5-for-5 day at the plate in the Islanders 9-5 loss to the Salt Lake City Bees. Despite slipping to a .255 average in the second half, he finished the season with a .266/.361/.436 line in 523 at-bats while placing among the circuit leaders with a career best 21 home runs. “I think Satriano has the equipment to make good as a major league,” Islanders manager Irv Noren said. “[He] is intelligent [and] always hustles.”6

Among the Angels late-season call-ups, Satriano made nine appearance (two starts) through September 25 before getting a start against the Detroit Tigers the next day. After a flyout to right field in his first at-bat, he got four consecutive hits, including an eighth inning leadoff homer, and three RBIs in helping lead the Angels to an 8-5 win. But his defense garnered the most notice during his September recall. “Satriano has the quickest hands of any player on our squad,” Rigney claimed. “It is almost impossible to get the ball by him in infield practice.” Looking ahead, the skipper added, “I intend to give him every chance to win the third base job [in 1963.]”7

But Rigney’s intentions were delayed when, due to a six-month commitment with the US Army reserve at Fort Ord, California, Satriano couldn’t report to spring training until 12 days before the start of the 1963 season. Retained by the club as a utilityman, the youngster’s rustiness from the abbreviated training camp was evident in limited regular season play. In May, after collecting just two hits in 20 at-bats through the first month, the Angels sent him back to Hawaii. Struggling to an anemic .219 average over 63 appearances, Satriano was demoted to the Class-AA Nashville Volunteers in the Southern Atlantic League with instructions from Rigney and Angels GM Fred Haney to give him a try at catcher. Despite five passed balls and three errors in just 24 games behind the plate (he also made 21 appearances at third), his nine assists from behind the plate attracted attention. On September 24, following his late-season recall, Satriano made his major-league debut as a catcher following a fruitless eighth inning pinch-hit appearance. With two outs in the ninth, he nailed New York Yankees infielder Phil Linz trying to steal second base. Four days later, in the last game of the season, Satriano started at catcher, the first of his 272 career starts there.

The Angels had greater designs for Satriano than as a mere backup catcher behind starter Buck Rodgers. In the 1964 spring training the club, with an eye toward converting their former bonus baby into a super-sub, began using him at first base. Satriano’s prospects improved considerably when, for the first time in his career, he produced in the cactus league: a .325 average with a team leading 16 walks in 23 games. On April 26, in his first start of the season, Satriano got three hits and three RBIs in a 7-0 win over the Indians. Three days later, in the first of six straight games in which he hit safely as a starter, Satriano had a perfect day at the plate with three hits and a walk in a 5-1 win against the Senators.

But his performance stalled in June. In 14 appearances (eight starts) through June 28, Satriano(now moved to third following the June 11 acquisition of first baseman Vic Power) plunged into a 1-for-30 slump. The rest of the season saw little improvement: a meager .174/.240/.228 line in a little less than a hundred at-bats. Though he played mostly at the corner infield positions, Satriano also served as the club’s primary backup catcher. This role appeared in jeopardy when the Angels acquired catcher Phil Roof from the Milwaukee Braves during the offseason.

In March 1965, Satriano’s chances of retaining his super-sub role diminished considerably when he suffered a separated shoulder and missed three weeks of spring training. Before the start of the regular season the club sent him to the Seattle Angels in the PCL. In the turnstile of half-a-dozen catchers Seattle used that season, Satriano batted a meager .173 in 110 at-bats. The Angels catching was hardly better. Rodgers, who suffered with an ankle injury and other ailments, and Merritt Ranew, who had replaced Roof as the backup, combined for a .209 average throughout the season. On June 15, the Angels, looking for versatility and willing to overlook the offensive challenges, recalled Satriano when Roof was sent to the Indians for cash and a player to be named later. Though his defensive work—just one error in a combined 117 chances at catcher and three infield positions—proved solid, Satriano’s offense continued to lag: .165/.258/.228 in 79 at-bats. “I can’t afford any more bad years,” he acknowledged after the season. “I feel my career has reached the urgent state.”8

His opportunities to mount a rebound appeared bleak when, during the offseason, the Angels purchased veteran backstop Ed Bailey from the Chicago Cubs. Through the first four weeks of the 1966 season Satriano got only eight at-bats over 15 appearances, mostly as a backup first baseman (only one start at catcher). But at 35 years old, Bailey had reached the end of his usefulness. When the former All Star catcher was released on May 7, Satriano stepped into the role as the club’s regular backup catcher. A month later he briefly moved into the starting job after Rodger, playing with a broken thumb, saw his batting average dip below .200.. On June 24, Satriano delivered a 14th inning walk off bases loaded RBI single to lead the Angels to 5-4 win over the Orioles. Four weeks later, after Rodgers returned to the lineup and Satriano played occasionally at the corner infield positions, he drove in the winning runs with a ninth inning two-run triple against righthander Jim Bouton in a 6-4 victory over the Yankees. Satriano finished the season with a .239/.320/.288 line with a career high three triples in 226 at-bats.

In 1967, Satriano had a brilliant spring training including a March 31 game against the San Francisco Giants in which he accounted for all the Angels scoring with six RBI on a single and homer in a 10-6 loss. Other teams, the Orioles, Yankees and Pittsburgh Pirates. pursued him aggressively throughout the spring, but nothing came of this. Starting at catcher for a sidelined Rodgers, Satriano opened the season by reaching base seven times in his first nine plate appearances: two walks and five hits, including his first home run in two years. When Rodgers returned, Satriano eventually moved to third base, replacing veteran Paul Schaal who was mired in a season long slump. Alas Satriano was a poor replacement: a 3-for-31 slog through August 16 returned Satriano to his familiar role of super sub. He finished the season .224/.319/.318 in 201 at-bats.

Despite starting just one game through the first 21 of the 1968 season, it proved to be Satriano’s finest. With two outs in the seventh inning of a game against the Oakland Athletics on April 27, he drove a single to right field to breakup what would’ve been future Hall of Famer Catfish Hunter‘s first no-hitter. . A week later Satriano started behind the plate for the first of five consecutive games after Rodgers was sidelined with a strained left shoulder. The pair platooned at catcher for the rest of the season. (Satriano also made 26 appearances in the infield.) On May 27, Satriano got a 12th inning walk-off RBI double against reliever Daryl Patterson for a 7-6 victory over the Tigers. Eight days later he delivered a 10th inning game winning pinch-hit RBI single with the bases loaded in the Angels 8-6 victory over the Orioles. Through June 7 Satriano led the Angels in hitting with a .292 average. “Satch biggest improvement . . . is as a hitter,” manager Rigney said. “He’s attacking the ball now. Some guys just develop late and I think he might be one of them.”9

Satriano continued attacking the ball. On August 11, he tied a franchise record with five hits in a game during an 11-1 shellacking of the Orioles. Six days later Satriano’s fourth inning two-run homer against righthander Camilo Pascual ignited a 5-3 comeback win over the Senators. Sidelined for 10 games with a hairline fracture of his left thumb, Satriano returned to the lineup on August 30 and connected with second baseman Bobby Knoop for homers on consecutive pitches against Catfish Hunter in a 5-3 win over the Athletics. Satriano finished the season with career high marks in hits (75), doubles (9), homers (8), RBIs (35) and total bases (108) in route to earning the club’s MVP honors. Moreover, the strong-armed catcher placed among the league leaders with 28 runners thrown out stealing.

As the 1969 season got underway Satriano, Rodgers, and shortstop Jim Fregosi were the only original Angels to last through the first eight seasons of the club’s existence. Within a year only Fregosi could claim so. Satriano, who received a series of mixed messages before his departure, existed first. During the offseason, after the Angels projected him as the club’s number one catcher, the unsigned Satriano cracked, “Maybe I should holdout for $75,000. Would that be a record for a hitter with a .215 lifetime average?”10 But in March 1969, when Senators outfielder Frank Howard held out for more money, the Angels reportedly offered a substantial package—Satriano, pitcher Clyde Wright, outfielders Vic Davalillo and Roger Repoz plus $100,000— for the All-Star slugger. Howard ended the speculation by re-signing with Senators days before the start of the season.

But Satriano’s days with the Halos were numbered. He started the 1969 season with three hits in his first three at-bats in route to a .352 average through the first month. On April 29, he deprived another pitcher, Seattle Pilots righthander Marty Pattin, of a no-hitter with an eighth inning two out single to centerfield. But Satriano’s average dropped nearly 100 points when he endured a 4-for-37 slump through June 3. Moreover, the offseason acquisition of knuckleball hurlers Hoyt Wilhelm and Eddie Fisher strained his behind-the-plate prowess. He surrendered eight passed balls in his 36 games at catcher.11

But it was events transpiring 2,500 miles away that ended his tenure with the Angels. On June 9, backup Red Sox catcher Joe Azcue, unhappy with his lack of play, bolted the team. Wasting little time searching for an alternate home for the disgruntled veteran, the Red Sox found one in the Angels. On June 15, the trading deadline, Satriano was sent to Boston for Azcue. Though he had recently been voted as the Angels player-representative after the incumbent, Bobby Knoop, was traded to the Chicago White Sox in May, Satriano gladly surrendered these responsibilities to join a pennant contender. “I regret leaving my home and friends in Southern California, but this is a great opportunity,” he gushed. “It’s a chance to . . . play in a World Series.”12 Though Satriano would never get that opportunity, he did not lack of playing time as did his predecessor. Moved immediately into a platoon with incumbent Red Sox catchers Russ Gibson and Jerry Moses, throughout the remainder of the season Satriano made 44 appearances (37 starts) behind the plate. (And it would’ve been more if not for a split finger that caused him to miss most of August).

The 1969-70 offseason was rife with rumors of Satriano’s departure from Boston. The Montreal Expos were reportedly aggressively pursuing the 29-year-old. But Boston wanted to retain a lefthanded hitter, so on April 4, three days before the start of the 1970 season, the club instead sold Gibson to the Giants. Satriano rode the bench through the first three weeks of the season, but on April 29 he was paired with struggling veteran righthander Sonny Siebert. Pleased with the results, manager Eddie Kasko had Satriano catch Siebert’s next start, a three-hit shutout against the Milwaukee Brewers. The battery remained intact throughout most of the season. But in September, the Red Sox turned increasingly toward minor league call-up Bob Montgomery. On September 19, Satriano got the start behind the plate in the second game of a doubleheader against the Senators. It would be his last major league appearance: he got an infield single and scored a run in three at-bats in the Red Sox 11-3 win.

The emergence of Montgomery, combined with the offseason acquisition of White Sox veteran backstop Duane Josephson, ended Satriano’s tenure in Boston. The team released him April 7. Signed by the Hawaii Islanders, now a San Diego Padres affiliate, Satriano platooned behind the plate with former Angels teammate Merritt Ranew and former Padres backup catcher Ron Slocum. Despite his considerable production—a .271/.452/.391 line in 133 at-bats—Satriano soon tired of the sporadic minor-league play and, on July 16, announced his retirement.

During the off-seasons, Satriano returned to the University of Southern California where he eventually earned a bachelor of science degree in general business management. In 1967, he joined the consulting firm of Pricewaterhouse as a tax auditor before opening his own consulting firm, Satriano and Hilton, Inc. in Brentwood, California. He sold the firm in 2000, after 25 years of operation. But he still continued dabbling in baseball, too. In August 1973 Andy Messersmith, the Angels All Star righthander, credited Satriano for helping his career by suggesting a different grip on the baseball.13

On February 8, 1964, Satriano married Sherry Lucia Mastrippolito months after the couple met on the field at Dodger Stadium (the Angels 1962-65 home) during a camera day promotion. Four years his junior, Sherry was born in Michigan but grew up on the outskirts of Los Angeles. The union produced three children before ending in divorce in September 1979. During their time together, the couple purchased 40 acres in Ventura County where they raised and bred Arabian horses. Satriano married twice more, having two children with his second wife and a daughter with the third. His eldest daughter Gina became the first female to play Little League baseball in Southern California.14 And in the 1990s, she put her budding law career on hold to play two years of professional baseball with the barnstorming all-female Colorado Silver Bullets.15

In the 1960s, after securing his bachelor’s degree, Satriano “admit[ted] there were times I thought about quitting. But I just love baseball too much.”16 As is the case with the vast majority of players, the Angels first bonus baby stayed with the sport and finished a decidedly unglamorous 10-year career with a .225 average with 21 homers, 157 RBIs, 130 runs scored, and -0.5 WAR—the very epitome of a journeyman backup catcher.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank SABR members Bill Mortell for his invaluable research and Tom Schott for review and edit of the narrative. This biography was fact-checked by Stephen Glotfelty.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Ancestry.com and Baseball-Reference.com.

Email with Tom Satriano, May 2-3, 2017.

Notes

1 Ross Newhan, “Versatile Tom Finds Niche as Angel Catcher,” The Sporting News, January 15, 1966: 20.

2 Ibid., “Busiest Angel Satriano Handles 5 Jobs,” April 22, 1967: 17.

3 Frank Finch, “Dodgers Limp East on Wing and a Prayer,” ibid., May 21, 1958: 25.

4 A fourth appearance, one that would have included his first hit—a home run against the Baltimore Orioles on August 6—was erased by a rain cancellation.

5 Bob Addie, “Bob Addie’s Atoms…” ibid., October 11, 1961: 15.

6 Braven Dyer, “Satriano Shapes Up as No. 1 Twinkler at Angels’ Hot Corner,” ibid., January 5, 1963: 34.

7 Ibid.

8 Newhan, “Versatile Tom Finds Niche.”

9 John Wiebusch, “Angels Gain New Firepower in Versatile Satch’s Big Bat,” The Sporting News, August 31, 1968: 20.

10 Ibid., “Handyman Satriano to Arrive in Camp as Top Angels Catcher,” January 25, 1969: 40.

11 Angels starter George Brunet occasionally added the knuckleball to his repertoire as well. Satriano also made seven appearances in the infield during this time.

12 Ross Newhan, “Angels Spread Big Swap Net; Azcue Is Lone Catch,” The Sporting News, June 28, 1969: 22.

13 Steve Buckley, Boston Red Sox: Where Have You Gone? (Champaign, IL.: Sports Publishing LLC, 2005), 115.

14 David W. Myers, “Where Are They Now? Tom Satriano,” Los Angeles Times, June 22, 1994. Accessed April 17, 2017 (http://lat.ms/2oFl2G7 ).

15 One of Gina Satriano’s teammates, Michele McAnany, was the daughter of Jim McAnany, a onetime opponent of her father’s.

16 Wiebusch, “Angels Gain New Firepower.”

Full Name

Thomas Victor Nicholas Satriano

Born

August 28, 1940 at Pittsburgh, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.