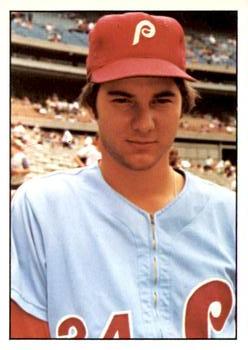

Tom Underwood

Versatile Tom Underwood enjoyed an 11-year major-league career (1974-84) pitching for six teams. He was a quick worker with a smooth delivery, underrated fastball — Pete Rose called it “sneaky” — and “one of the best curves of any lefthander.”1

Versatile Tom Underwood enjoyed an 11-year major-league career (1974-84) pitching for six teams. He was a quick worker with a smooth delivery, underrated fastball — Pete Rose called it “sneaky” — and “one of the best curves of any lefthander.”1

Officially listed at 5-feet-11 and 170 pounds, in his prospect years he was also identified as 5’9” and 5’10” and described as “Tiny Tom” and “Little Tommy Underwood.” Those monikers disappeared after he established himself in the major leagues and was traded away from his first team, the Philadelphia Phillies.2

Thomas Gerald Underwood was born on December 22, 1953 in Kokomo, Indiana to John and Helen Marie (née Murphy). John Underwood played one season in the minor leagues in the Phillies organization before serving in World War II.3 After the war he served in the Indiana National Guard and accumulated 22 years of military service, retiring as a captain. He was also terminal manager for Motor Express.4

Young Tom grew up playing sports with his father and brothers Mark and Pat Underwood, who would himself become a major-league pitcher.5 The boys also had a sister named Nancy. Of his father, Underwood once said, “I owe a lot to my dad. . . . My brothers and I always had a glove on his hand to play catch the moment he walked in the door after work. He never said ‘no.’ I was very lucky.”6 Underwood pitched right-handed until switching arms at age 11, but continued to bat from the right side.7

Underwood graduated from Kokomo High School in 1972. In addition to quarterbacking the football team, he was 17-3 in his junior and senior years with an ERA of 0.40. During that same period Underwood was 25-1 in American Legion ball and helped Post 6, the area team, win the 1972 state championship. Subsequently, he became the first player from Howard County, Indiana to reach the major leagues and he was named Howard County’s greatest athlete of the 20th Century by the Kokomo Tribune.8

Underwood turned down an offer from the University of Notre Dame before signing a letter of intent with Western Michigan University.9 However, those plans were upended when on the day of the 1972 amateur draft, Phillies scout Tony Lucadello called farm director Dallas Green to rave about Underwood. Returning from a tournament game in which Underwood struck out 25 batters, Lucadello said he “had never seen a performance like” Underwood’s.10 Moved by Lucadello’s uncharacteristically enthusiastic recommendation, the Phillies drafted Underwood with the 27th pick and signed him without a review from a second scout.11

Underwood moved rapidly through the Phillies’ farm system. In 1973 he led Class A Spartanburg to the Western Carolinas League title with a 13-6 record while pacing the league in ERA (2.10) and strikeouts (187).12 The next season, as a 20-year-old, he won 14 games for Class AA Reading of the Eastern League before being called up to the Phillies in August. Underwood said the moment he was told he was going to the big leagues was the greatest of his career. He recalled, “It was like my feet were off the ground – it was a feeling that never went away.”13

Underwood made an inauspicious debut against the Cincinnati Reds on August 19, 1974. Arriving at Riverfront Stadium straight from the airport, he entered the game in the third inning. He struck out his first batter, Dan Driessen, before six straight Reds reached base, culminating with a grand-slam home run from future Hall of Famer Joe Morgan.14 After the game, a 15-2 Reds victory, Underwood said he was “too numb to feel anything.”15 However, Reds manager Sparky Anderson saw it as a positive learning experience for Underwood, explaining, “Tell that kid it might be the best thing that ever happened to him. Now he knows it is not easy up here.”16 Underwood bounced back from the “merciless thumping” that gave him a 162.00 ERA in his debut. Over the remainder of the season, he surrendered only a single earned run across six relief appearances spanning 12 2/3 innings.17

Hopes were high that Underwood would help lift the Phillies into pennant contention. When taking stock of Phillies arms at the end of 1974, Today’s Post correspondent John Shiffert speculated that Underwood “may prove to be the best” of the Phillies’ pitching prospects. Drawing on his minor league success, Shiffert contrasted Underwood, “a little lefthander,” with flame-throwing youngsters who had high velocity but knew little about pitching.18 Further, in advance of the 1975 season, future Hall of Fame pitcher Jim Bunning called Underwood “the best lefthanded pitching prospect I’ve ever seen.” Phillies manager Danny Ozark added, “He’s little but mighty, and he’s got the guts of a burglar.”19

Impressed by his stuff, poise, and attitude, the Phillies made Underwood their fourth starter after a strong spring training in 1975.20 In turn, Underwood showcased the promise Bunning, Ozark, and others saw when he threw a 2-0 shutout against the St. Louis Cardinals in his first major-league start on April 13, 1975. Six starts later he avenged his 1974 debut against the Reds by pitching a six-hit complete-game shutout against the team that would win the next two World Series titles.

In his first full season, Underwood won a career-high 14 games while starting 35, completing seven, and hurling 219 innings. In recognition of his success, he was named to the Topps all-rookie team.21 His promise was such that a September 1975 Baseball Digest profile by Bill Lyon effusively asked if Underwood was “A New Super Pitcher in the Making?” The article described him as possessing “a slider that is just plain nasty . . . and a changeup that sends batters to the chiropractor.” To that catcher Bob Boone added, “I think he’s gonna be a super pitcher. He’s got a good head and he doesn’t lose his cool.”22

In 1976 Underwood split the first two months of the season between starting and relieving, before claiming a rotation sport for his final 20 appearances. On the season he posted 10 wins and 2 saves for the National League East Champion Phillies while lowering his ERA more than half a run, to 3.53. Philadelphia went with a short rotation for the National League Championship Series against the Reds, so Underwood found himself in the bullpen. Down 2-0 in the series, the Phillies entered the bottom of the ninth of Game Three up 6-4. After Ron Reed surrendered home runs to George Foster and Johnny Bench, and Gene Garber gave up a single to Dave Concepción, Underwood was summoned to the mound. He walked the first hitter he faced, Cesar Geronimo, before recording an out on a sacrifice. Underwood was then ordered to intentionally walk Pete Rose to load the bases. The game, and the series, ended when Ken Griffey scratched out an infield single.23

The 1977 season started poorly for Underwood. That June, the Phillies traded him to the Cardinals in a deal that brought speedy Bake McBride to Philadelphia. The apparent “considerable cost” to the Cardinals made some people in St. Louis skeptical of the trade, particularly given Underwood’s slow start. Underwood contended that his struggles came from being used exclusively out of the bullpen that season. He protested, “I’m a starter, not a relief pitcher.”24 Tellingly, the Cardinals were not the only team interested in Underwood. The Cubs were “miffed” that their proposed deadline deal failed, with Cubs general manager Bob Kennedy dismayed over how his proposed deal imploded.25

Despite starting for St. Louis, Underwood proved “wild and ineffective much of the” remainder of the season and posted the highest ERA of his career (5.00). In the winter he was traded again, this time to the Toronto Blue Jays, who had just completed their inaugural season.26 Having already been traded once, Underwood felt ready for the second move, sharing that the trade from the Phillies “really bothered me. . . . But it also made me realize that trading is part of baseball and it helped prepare me for the trade to Toronto.”27

Underwood pitched effectively as a starter for the Blue Jays in 1978 and 1979, but the expansion team provided him with little run support.28 After a solid 1978 season in which he pitched 197 innings over 30 starts and struck out 139 batters (10th in the American League), it was noted that the Yankees maintained “more than passing interest” in Underwood. However, it would be another year before a deal to New York materialized.29

Underwood began 1979 as the Blue Jays’ number two starter, in a season that proved to be one of his best but least satisfying. 30 He started the year 0-9 and voiced his frustrations to Murray Chass of the New York Times, saying, “I’m not a 20-game loser but I have a good chance of doing it. I don’t even know how I’ve lost 10 games.” The disgruntled Underwood continued, “I’ve got too much pride to go out and pitch well and lose. I have too much good stuff to lose games, even with Toronto.”31

In compiling a 2-11 midseason record, Underwood suffered as the Blue Jays were shut out four times when he was on the mound and managed just one run in four of his other starts.32 In his 1979 story, Chass noted that the Yankees continued to have interest in Underwood, and “they have seen nothing that would discourage them from possibly pursuing him between now and next season.”33 Despite finishing the season 9-16, Underwood had perhaps his best season as a starter, with career highs in innings (227) and complete games (12) while compiling a 3.69 ERA.

Underwood’s 1979 season also featured a notable event. The Jays’ game against Detroit on May 31 remains the only time in major-league history (as of 2020) when one brother made his pitching debut against another, as Pat Underwood started for Detroit.34 Tom was less than thrilled about the matchup. He commented beforehand, “I think it’s stupid. . . . I’m not sure it’s really fair to Pat. There’s enough pressure on you when you’re pitching your first game in the big leagues without worrying about your brother.”35

The Blue Jays arranged for Tom and Pat’s mother Helen Marie to travel from Kokomo to attend the game.36 Understandably conflicted about the matchup, she said, “I prayed for rain.”37 While both brothers pitched magnificently, Pat secured a 1-0 victory after Tom surrendered an eighth-inning solo home run to Jerry Morales. After the game, Tom proudly commented, “I’m awfully happy for Pat. He pitched great and deserved to win.” He added, “I taught him [Pat] how to throw a slider and changeup while he was in high school. When I looked out, I felt like I was watching myself.”38

Following the season, with Underwood a year away from becoming a free agent, the Blue Jays heeded his suggestion that it would be better to trade him than get nothing in return. Thus the Yankees’ interest in Underwood was fulfilled as they acquired him and catcher Rick Cerone, for Chris Chambliss and minor-leaguers Paul Mirabella and Dámaso García.39 The lefty pitcher Mirabella did little with the Jays but went on to pitch in the major leagues for parts of 13 seasons, while second baseman García became a two-time All-Star.

As New York sportswriter Phil Pepe explained, the Yankees had been “eyeing Tom Underwood’s left arm for years.” Pepe added, “It wasn’t by accident that Underwood became a Yankee, it was by design.”40 Underwood was equally pleased to join the Yankees, saying, “I’ve waited two years to get with a team that can win. . . . there is no team” the Blue Jays “could have traded me to that would have made me happier.”41 This joy may have contributed to Underwood’s decision to sign a four-year contract with the Yankees prior to the 1980 season.42

Despite the high expectations, staff injuries forced Underwood to begin the year in the Yankees’ bullpen. Although he maintained a preference for starting, he was willing to do whatever he could to help the ball club. Manager Dick Howser liked the flexibility Underwood provided, remarking, “I feel so comfortable when that guy’s out there.”43

By the middle of May, Underwood was in the starting rotation and pitching some of the best baseball of his career. On June 7, he allowed only three hits in 8 2/3 innings and beat the Mariners 1-0. He was backed by future Hall of Famers Reggie Jackson, who hit his 379th home run, and Rich “Goose” Gossage, who threw one pitch to record the save.44 The victory was Underwood’s fifth in a row and he felt rejuvenated: “I never lost faith . . . . when things were going the worse for me during that losing stretch [with the Blue Jays], I said to myself that when things start to break even, I’ll have about 35 wins in a row coming to me.”45

Underwood’s performance, which helped propel the Yankees to their best 50-game start since 1958, prompted Daily News reporter Norm Miller to ask excitedly, “What was the last team you can remember with a dynamite 1-2-3 left-handed firing line like Ron Guidry, Tommy John and Underwood?”46 For his part, Underwood contended he was the same pitcher who started 0-9 in 1979. As Phil Pepe reported, “There is nothing different about Tommy Underwood between this year and last, nothing added, nothing subtracted. He is still a pitcher in the major leagues, still lefthanded, still a bachelor, still lives in Kokomo, Ind., in the off-season, and he still throws that good curveball. Only the record has been changed.”47

Alas, the accolades were short-lived. Within a month, Underwood had gone into a slump with three straight starts in which he failed to get out of the fourth inning, including one in which he didn’t retire a single batter. “It’s all in my head. . . . I put too much pressure on myself,” he told the New York Times in July. “I let too many things affect me. There’s been too much going on in my head that’s been interfering with my pitching.”48 However, Underwood soon bounced back with an excellent three-hit seven inning performance in a 11-1 Yankees win. For the season he recorded 13 wins, the second-highest total of his career, and two saves for the 1980 American League East Champs. He started 27 games among his 38 appearances and logged 187 innings. He made two relief appearances in the AL Championship series and again found himself on the mound for his team’s final postseason inning as the Yankees were swept by the Kansas City Royals.

Underwood started the strike-shortened 1981 season with the Yankees before being traded for the fourth and final time, joining Billy Martin’s Oakland A’s. Upon obtaining Underwood, Martin briefly moved to a novel six-man starting rotation. He planned to use Underwood, the only lefthander in the group, against lefty-heavy lineups like the Yankees and Tigers.49 However, the experiment was quickly abandoned and Underwood spent most of the remainder of the season in the bullpen.50 Still, he ended the regular season on a high note, pitching a complete game on September 29, 1981 with a career-high 10 strikeouts in a 5-1 victory over the Blue Jays.51 In postseason play for the third and final time in his career, Underwood made three relief appearances. Just as had been the case in his first two years in postseason play, Underwood pitched his team’s final inning of the season as Oakland was swept three games to none by his former Yankee teammates in the American League Championship Series. If not entirely unique, it is certainly peculiar that Underwood was his team’s final pitcher in all three postseasons in which he appeared, even though he did not suffer the loss in any of the games.

Working in a swing role for Oakland in 1982, Underwood enjoyed arguably the greatest success of his career as he made 46 relief appearances and 10 starts. The performance earned high praise from manager Martin: “He’s a very special kind of pitcher. . . . We’ve asked him to relieve quite a bit and start when we need him. Right now, I’d say he’s become a complete pitcher in both respects, and it takes a very special person to do that.”

Nonetheless, in July 1982 Underwood professed his continued desire to be a starting pitcher, explaining, “To accomplish what I want to get out of baseball, I can do it best starting. . . . I’m a firm believer in preparation, which you need to be a starter.”52 However, it was difficult to argue with the results and in August, after working 16 scoreless innings across eight appearances, the “jack-of-all-trades” Underwood had lowered his ERA to a league-leading 2.87.53 For the season Underwood won 10 games, saved seven, and recorded a 3.29 ERA, sixth best in the AL among pitchers who threw 150 or more innings.

Underwood continued in his role as a reliever and spot starter in 1983, making 15 starts among his 51 appearances. In the final year of his contract, he expressed hope that the A’s would sign him to an extension rather than trade him. Still, he was realistic, noting, “I’m a lefthander, I’m on the last year of my contract and my value is higher than it has ever been. . . . They are going to get something good for me.”54

At the same time, Underwood’s continued success changed his view on being exclusively a starting pitcher. As he explained it in July 1983, “I was going six innings a start and then sitting down for five days. . . . Why not go six innings in three different games. All I’m admitting is that I was wrong about myself.”55

As the season concluded Underwood was unhappy with the A’s noncommittal attitude toward his return. Offering the kind of candor that prompted one journalist to describe him as “outspoken,” he contended, “If they want me they should come up to me and say, ‘We want you and this is what you are worth,’” He also defended his value: “There is nobody here right now who can do the job that I do. . . . That’s not a ploy for money. This is a nine-year veteran who is talking about something he knows is a fact.”56

Based on his performance during the previous two years, Underwood was classified as a “Type A” free agent, meaning that the A’s would receive player compensation if he signed with another team. As a result, the 30-year-old hurler drew interest from only the Cleveland Indians in the major-league player re-entry draft. Bill Conlin lamented the situation in The Sporting News, writing that Underwood’s Type A classification led him to be “shunned like a man with leprosy because of the Catch-22 that is compensation.”57

While not voicing his opinion with as much color, Underwood essentially agreed with Conlin’s assessment. “It didn’t come down to much interest at the end. . . I think being a Class A player turned” teams off.58 Because of his desire to pitch for a winning team, Underwood turned down a three-year offer from the Indians in favor of a one-year contract plus two team options from the Baltimore Orioles. As Underwood explained, “Despite the guaranteed offer (from Cleveland) there was no comparison. Baltimore was my first choice. This is a great opportunity. I know when a good thing comes along.”59

Inadvertently, Underwood found himself in the middle of a confusing and contentious rules snafu over free agent compensation. Under the system that was created as part of the resolution of the 1981 labor stoppage, once Underwood signed with Baltimore, the A’s selected Tim Belcher as compensation. Belcher, selected by the Yankees as the #1 pick in the 1983 amateur draft, was not on the Yankees’ list of protected players because he had signed his contract so late. Peter Gammons called the loss of Belcher “one of the biggest blunders of modern times.” The irate Yankees complained that they were “shocked” Belcher was “ruled eligible” for the compensation draft.

Lee MacPhail, director of the Player Relations Committee, sympathized to an extent in recognizing that “The Yankees have become the victims of a very unfortunate set of circumstances.”60 Joining the dispute, Donald Fehr, executive director of the Major League Players Association, protested that the system “diluted the bargaining power” of Underwood and other free agents and the selection of Belcher revealed “very serious problems with the whole compensation system.”61

At the time of his signing, Underwood expected to be used by the Orioles in the same way that had produced so much success in his last two seasons with the A’s: “I’ve had a certain amount of success doing everything from starting to pitching in relief, and I think I’m most valuable when I don’t have a given role.”62 However, instead he was relegated largely to pitching in mop up situations (the Orioles were 7-30 in games in which Underwood pitched). And the Orioles informed an unhappy Underwood at the end of the season that his option would not be picked up.63

Attracting little interest over the winter, Underwood expected to retire. However, late in the spring he was motivated to continue pitching. In early June 1985, he flew to Milwaukee to audition for a job with Billy Martin and the Yankees. Martin felt that Underwood “looked exceptionally good” in a bullpen session. Underwood admitted to being “a little worried” about the attempted comeback and was open to anything the Yankees suggested: “I’ll go anywhere they want me to. . . It’s not like I’m in the position to argue around here.” And if it didn’t work out? “I’ll pitch a double-header with my brother Pat on Sunday” for the semipro Kokomo Highlanders.64

Underwood signed a minor league deal with the Yankees but could not find consistent success. After posting a 5.17 ERA in 28 games with three minor-league affiliates, he was released at age 31.

Underwood’s major-league career totals featured an 86-87 record with 18 saves and a 3.89 ERA. He made 379 appearances, 203 of them starts, and threw 35 complete games with six shutouts across 1,586 innings. Reflecting on his career in 1999, Underwood recalled his experiences, fondly saying, “For 10 years I saw the entire U.S. for free and had five months vacation. I just wish I could have played the game longer.”65

Shortly after his baseball career ended, Underwood met his future wife, Christine Morra, a professional golfer.66 The couple moved to West Palm Beach, Florida, and he worked for 20 years as a financial advisor. He also had the opportunity to play for the West Palm Beach Tropics in the short-lived (1989-1990) Senior Professional Baseball Association.67 He greatly enjoyed the experience and the fact that Christine and his infant daughter Dani (short for Danielle) would attend the games: “My wife and daughter come to every game. I really like looking into the stands and seeing them there.”68

The Underwoods soon became parents a second time with the birth of John Dominick (J.D.), named after Tom’s father. J.D. was drafted in the fifth round of the 2013 amateur draft by the Los Angeles Dodgers and spent three years in their system as a righthanded pitcher before electing to leave baseball.69 Of Underwood, Christine said, “Tommy says he has two careers. . . His first career was playing baseball, and we’re the other.”70

Tom Underwood passed away on November 23, 2010, at age 56, after an 18-month battle with pancreatic cancer.71 In addition to his children, he was survived by Christine, his wife of 24 years. He was remembered by family and friends for his personality, humor, and happiness.72

His son J.D. recalled his father as “the toughest, most optimistic person I’ve ever been around. . . . he worked his butt off at anything he did, and that included fighting cancer.”73 In honor of his father, J.D. has a tattoo with a baseball and his father’s initials, along with an inspirational message his father would often deliver to him: “Winners always win without their best stuff.”74

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Pat Underwood for participating in a telephone interview (February 6, 2020).

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Joe DeSantis and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In preparing this biography the author also consulted Underwood’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, New York and statistics from Baseball-Reference.com.

Bruce Markusen also effectively captures the arc of Underwood’s career as part of his Card Corner series: Bruce Markusen, “#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Tom Underwood,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/card-corner/1981-tom-unde….

Notes

1 Neil MacCarl, “Underwood Goal: Avoid 20 Losses,” The Sporting News, July 28, 1979, 23; Ray Kelly, “Home’s a Sweet Place for Underwood’s Victories,” The Sporting News, September 27, 1975, 8; Phil Pepe, “Lefty Underwood Fits Right In,” National Baseball Hall of Fame Library player file.

2 Frank Bilovsky, “Lucadello Bellowed to Grab Underwood,” Philadelphia Bulletin, April 16, 1975; Kelly, “Home’s a Sweet Place”; Ray Kelly, “Phils Plan Big Future for Tiny Tom,” January 4, 1975, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library player file; Ray Kelly, “Underwood Living Up to Rave Notices,” The Sporting News, May 3, 1975, 8.

3 Pat Underwood, telephone interview with Todd McDorman, February 6, 2020; Hugh Bernreuter, “Dodgers Prospect J.D. Underwood Keeps Father Close through Tattoo, Memories,” MLive, May 1, 2015, https://www.mlive.com/loons/2015/05/dodgers_prospect_jd_underwood.html.

4 “Helen Underwood,” Kokomo Tribune, July 7, 2002, 2; “John D Underwood,” Kokomo Tribune, July 7, 2003, 10.

5 “Thomas Gerald Underwood,” Kokomo Tribune, November 23, 2010,

https://obituaries.kokomotribune.com/obituary/thomas-underwood-717183261.

6 “Cancer Claims Kokomo Great Tom Underwood,” Kokomo Tribune, November 23, 2010, https://www.kokomotribune.com/sports/cancer-claims-kokomo-great-tom-unde….

7 Kelly, “Home’s a Sweet Place”; Ray Kelly, “Righty or Lefty? Underwood Dazzles Phil Brass,” The Sporting News, March 22, 1975, 44.

8 “Cancer Claims.”

9 Kelly, “Righty or Lefty?”

10 Bilovsky, ‘Lucadello Bellowed.”

11 Kelly, “Underwood Living.”

12 John Shiffert, “Phils May Go Over the Top with Underwood,” Today’s Post, October 3, 1974.

13 “Cancer Claims.”

14 Ray Kelly, “Phils Plan Big Future.”

15 United Press International, “Phils Underwood Greeted,” August 20, 1974, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library player file.

16 Kelly, “Underwood Living.”

17 “Rookie ‘Welcomed,’” The Sporting News, September 7, 1974, 31.

18 Shiffert, “Phils May go Over.”

19 Kelly, “Righty or Lefty?”

20 Kelly, “Underwood Living.”

21Bruce Markusen, “#CardCorner: 1981 Topps Tom Underwood,” National Baseball Hall of Fame, https://baseballhall.org/discover-more/stories/card-corner/1981-tom-unde….

22 Bill Lyon, “Tom Underwood: A New Super Pitcher in the Making?,” Baseball Digest, September 1975, 46-47.

23 Earl Lawson, “Champ Reds Beat ‘Five Million to One’ Odds,” The Sporting News, October 30, 1976, 13.

24 Neal Russo, “Devine Fills Out His Hand with a Three-Card Draw,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1977, 8.

25 Jerome Holtzman, “Cubs Miffed Over Phils Trade Feelers,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1977, 8.

26 Neal Russo, ‘Templeton Gave Cards Plenty to Crow About,” The Sporting News, October 22, 1977, 33.

27 Neil MacCarl, “Underwood Likes Starting Prospect with Jays,” The Sporting News, January 14, 1978, 40.

28 Neil MacCarl, “Doerr’s Tip Ignites Griffin’s Bat Spree,” The Sporting News, June 30, 1979, 22.

29 Phil Pepe, “Steinbrenner Stashes Pen, But Changes Still Likely,” The Sporting News, December 16, 1978, 42.

30 Neil MacCarl, “Blue Jays Moving On ‘Right Track,’” The Sporting News, December 16, 1978, 51.

31 Murray Chass, “Underwood Fights Losing (1-10) Battle,” New York Times, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library player file.

32 MacCarl, “Underwood Goal.”

33 Chass, “Underwood Fights.”

34 “Tigers Top Blue Jays as Brothers Duel, 1-0,” New York Times, June 1, 1979, A19; “Brother Act in Toronto,” The Sporting News, June 16, 1979, 30.

35 “Tom and Pat Underwood: Brother, Can You Spare a Run?,” RetroSimba: Cardinals History Beyond the Box Score,” May 29, 2019, https://retrosimba.com/2019/05/29/tom-and-pat-underwood-brother-can-you-….

36 “Tigers Top Blue Jays.”

37 “Tom and Pat Underwood.”

38 Dave Kitchell, “Underwoods: Tom vs Pat,” Kokomo Tribune, June 1, 1979 (republished December 27, 2009), https://www.kokomotribune.com/sports/kitchell-underwoods-tom-vs-pat/arti… “Tom and Pat Underwood.”

39 Pepe, “Lefty Underwood.”

40 Pepe, “Lefty Underwood”; Phil Pepe, “Starting Job for New Yankee,” March 15, 1980, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library player file.

41 Pepe, “Lefty Underwood.”

42 Phil Pepe, “Autograph Buff Soderholm Finds Bonanza with Yanks,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1980, 50.

43 Murray Chass, “Underwood’s Talent a Problem for Yanks,” New York Times, April 24, 1980; Phil Pepe, “Underwood Yank Plum,” July 12, 1980, National Baseball Hall of Fame player file.

44 Parton Keese, “For Underwood, Persistence Pays,” New York Times, June 9, 1980.

45 Keese, “For Underwood.”

46 Norm Miller, “Guidry, John, Underwood: As Easy as 1-2-3,” New York Daily News, June 9, 1980.

47 Pepe, “Underwood Yank Plum.”

48 Murray Chass, “Yanks’ Underwood Seeks Cure for Slump,” New York Times, July 17, 1980, D17, D19.

49 Kit Stier, “Billy’s Mound Horses Jam Starting Gate,” The Sporting News, June 13, 1981, 28.

50 Kit Stier, “Page Gets Dropped in A’s Juggling Act,” The Sporting News, June 27, 1981, 39.

51 “Underwood Right,” The Sporting News, October 17, 1981, 18.

52 Kit Stier, “Underwood Excels Doing Double Duty,” The Sporting News, July 26, 1982, 34.

53 Kit Stier, “Critics Rip Billy in Murphy Affair,” The Sporting News, August 30, 1982, 36.

54 Kit Stier, “Rain-Drenched A’s Gripped by Slump,” The Sporting News, May 9, 1983, 24.

55 Kit Stier, “A’s Bullpen Full of Milquetoasts,” The Sporting News, July 25, 1983, 18.

56 Mike McAlary, “Yanks Audition Underwood,” New York Post, June 7, 1985; Kit Stier, “A’s Make No Offer to Underwood,” The Sporting News, October 31, 1983, 53.

57 Bill Conlin, “Noles Just May Win Bout with Alcohol,” The Sporting News, February 13, 1984, 44.

58 “Underwood Shuns Guarantee,” The Sporting News, February 27, 1984, 36.

59 “Underwood Shuns,” 36.

60 Peter Gammons, “Frazier Might Be Ready for Stardom,” The Sporting News, February 24, 1984, 36; Moss Klein, “Yanks Lose Belcher, Protest Rule,” The Sporting News, February 20, 1984, 40; Kit Stier, “A’s Choosing Belcher Stuns Yanks,” The Sporting News, February 20, 1984, 41.

61 “Fehr Challenges Compensation Rule,” The Sporting News, February 27, 1984, 35.

62 “Underwood Shuns,” 36.

63 Jim Henneman, “Singleton, Bumbry Won’t Return in ‘85,” The Sporting News, October 15, 1984, 22; Mike McAlary, “Yanks Audition Underwood,” New York Post, June 7, 1985.

64 McAlary, “Yanks Audition Underwood.”

65 “Cancer Claims.”

66 Hal Habib, “Former Major Leaguer Tom Underwood Dies at 56,” Palm Beach Post, March 31, 2012, https://www.palmbeachpost.com/sports/former-major-leaguer-tom-underwood-….

67 “And Now . . . Over-35 Transactions,” The Sporting News, October 2, 1989, 25.

68 Tom Perry, “Senior Baseball Major for Underwood,” South Florida Sun-Sentinel, January 2, 1990, https://www.sun-sentinel.com/news/fl-xpm-1990-01-02-9001170125-story.html.

69 Underwood-McDorman interview.

70 Habib, “Former Major Leaguer.”

71 “Cancer Claims.”

72 “Thomas Gerald Underwood.”

73 Bernreuter, “Dodgers Prospect.”

74 Bernreuter, “Dodgers Prospect.”

Full Name

Thomas Gerald Underwood

Born

December 22, 1953 at Kokomo, IN (USA)

Died

November 22, 2010 at West Palm Beach, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.