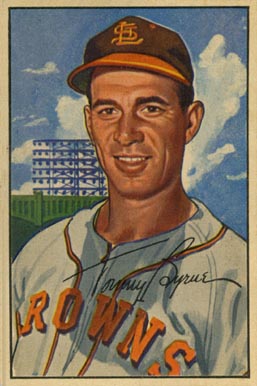

Tommy Byrne

Tommy Byrne had three careers and was successful in all of them. A hard-throwing left-handed pitcher, he spent thirteen seasons in the Major Leagues. His ball playing days over, Byrne turned to business, with considerable success. Then he devoted himself to politics, and served two terms as mayor of his adopted hometown.

Tommy Byrne had three careers and was successful in all of them. A hard-throwing left-handed pitcher, he spent thirteen seasons in the Major Leagues. His ball playing days over, Byrne turned to business, with considerable success. Then he devoted himself to politics, and served two terms as mayor of his adopted hometown.

Thomas Joseph Byrne was born in Baltimore, Maryland, on December 31, 1919, one of three sons of Joseph Thomas Byrne and Grace C. (Phenice) Byrne. The youngster’s favorite ballplayer was Babe Ruth, and he told friends he hoped some day to don the same pinstriped uniform of his hero.

Byrne first pitched for the Blessed Sacrament Elementary School team in the Baltimore Junior League. A neighbor, Philadelphia Athletics pitcher Eddie Rommel mentored Tommy on the finer points of pitching and instilled baseball savvy in the youngster that would stay with him throughout his career.

In his first year at City College high school, Byrne failed to make the freshman baseball team. In his second year, he made the junior-varsity squad, and was called up to the varsity late in the season to pitch in an exhibition game against the Naval Academy’s Plebe team. Tommy walked the first three batters and then settled down, leading his team to a 4–0 victory.

Finally installed on the varsity squad, Byrne dominated the Baltimore school baseball scene for the next two years. He helped guide City High to two undefeated seasons and a pair of Maryland Scholastic Association championships. During the summer months he hurled in the Baltimore amateur leagues with the Oriole Juniors and the Joe Cambria All Stars.

After graduating in 1937, Byrne had an opportunity to sign with the Detroit Tigers. He traveled with the club for part of the summer. The Tigers offered him a $4,000 signing bonus and a roster spot on their Texas League farm club in Beaumont. But Byrne, an excellent student, wanted to go to college and turned down the offer.

Duke University offered a scholarship that would have required him to work in the school cafeteria to defray some of his expenses. A friend in Baltimore, who had a connection with Wake Forest College, told Byrne he could get a scholarship there without having to work.

When Byrne got off the train in Wake Forest, North Carolina (the college had not yet moved to Winston-Salem and become a university), he was instantly smitten with the small-town atmosphere. He struck up an immediate friendship with baseball coach John Caddell. Byrne lived with the Caddell family during his stay at the school and as their bond grew, he eventually, came to know the coach and his wife as his adoptive parents.

Byrne was a mathematics major in the classroom and a standout pitcher on the Wake Forest baseball team for three seasons. He defeated Duke nine of the ten times he faced them. He also fanned seventeen in a game against Cornell. During the summers, Byrne played in the semiprofessional Tobacco State League. He was scouted by Yankees regional scout Gene McCann and signed with New York on July 4, 1940. He received a $10,000 signing bonus and a $650-a-month salary. The Philadelphia Athletics had offered Byrne more money, but he was determined to play on the same team as his boyhood idol, Babe Ruth.

The Yankees started Byrne with their top farm club, the Newark Bears of the International League. He struggled in his first season, winning two games and losing five. He did better in 1941 as the Bears won the first of two consecutive pennants, winning ten games and losing seven.

In 1942 Byrne hit his stride. He won seventeen games while losing just four, and while he gave up only 160 hits in 209 innings, he walked 145 batters. But Bears manager Billy Meyer said, “Wild or not, he is the best prospect in the International League, as his record shows. There is no reason he can’t get the ball over the plate in the majors.” At the plate, the left-handed hitting Byrne had ten doubles, two triples and two home runs while batting .328.

Byrne earned a spot on the Yankees’ 1943 roster, making his Major League debut on April 27, against the Boston Red Sox. He pitched only one inning, giving up no hits but a run on two walks. The rookie was with the Yankees for only a short time before enlisting in the navy. He won two games and lost one, but walked 35 batters in 31 2/3 innings. Byrne’s first major-league win came as a reliever in his second game, in Washington. To make the victory even sweeter, his mentor Eddie Rommel was umpiring at first base.

Byrne quickly grasped the Yankees tradition. “Part of the Yankee success lay in perpetuating the image,” he recalled in later years “From the moment you signed a contract with them they began instilling in you that Yankee tradition and they never stopped, not even when you were with the parent team. The attitude in those days was so great it was unreal. If we had a ballplayer on the Yankees who seemed to be doing things on his own, who didn’t appear to have had bred in him what it meant to play and win as a team, he wasn’t around too long . . . They just wouldn’t allow anyone, no matter how much ability he had, to tarnish that Yankee image. It meant too much, in ways that were as much practical as symbolic.”

Because Byrne was a college graduate with a degree in mathematics, the Yankees’ farm director, George Weiss, recommended him for Naval Officers Training School. Byrne was accepted and was commissioned an ensign in November 1943.

His first assignment was to the Norfolk (Virginia) Naval Base, where, like many ballplayers in uniform, he mostly played baseball. In the spring of 1944, Byrne posted a 16-2 record for the powerful base team, while playing in the outfield on the days he did not pitch.

Later, Byrne was assigned to the destroyer USS Ordronaux as the gunnery officer. In August 1944 he participated in the Allied invasion of the south coast of France, and was in charge of the ship’s guns as it shelled German shore defenses.

Discharged from the Navy in January 1946, Byrne rejoined the Yankees. But he made only four pitching appearances during the season, though he appeared in ten other games as a pinch hitter or pinch runner. Manager Joe McCarthy tried without success to get the six-foot-one, 182-pound Byrne to switch to first base. The highlight of the season for Byrne was probably Oldtimers Day at Yankee Stadium, when Babe Ruth asked to borrow his glove.

The emergence of rookie pitcher Frank Shea put Byrne’s 1947 roster spot in jeopardy. Byrne had pitched only four innings when on June 14 the Yankees sent him to the Kansas City Blues of the American Association. With the Blues Byrne won twelve and lost six, but gave up 106 walks in 149 innings.

Byrne was back with the Yankees in 1948 and finally started to find his groove in the majors, winning eight games and losing five. Still wild, he walked 101 in 133 innings and hit a league-leading nine batsmen. Coach Bill Dickey, who had been his first Major League catcher, taught Byrne a cut fastball, which curtailed the natural rising movement of his fastball. But the wildness remained. He led the American League in walks three years in a row (1949–1951) and hit batsmen in five seasons.

Even with his problems locating the strike zone, Byrne was considered a vital part of the Yankees squad, and got a raise in salary in each of three years he led the league in walks. “ … I never really believed in my own mind that I was so very wild,” he said in later years. “I didn’t think I was ‘losing’ wild, if you know what I mean. I used to feel that if they let me pitch I wasn’t going to give more than three or four runs a game, and I would get a couple back with my own bat, because I could hit.”

The Yankees had a new manager in 1949, Casey Stengel, and Byrne, with a 15-7 record had his best season to date. The Yankees defeated the Brooklyn Dodgers in the World Series. Byrne started the third game but was lifted in the fourth inning after giving up a home run to Pee Wee Reese and loading the bases on a hit and two walks.

Byrne was a methodical worker on the mound, taking an inordinate amount of time between pitches. He was a sociable fellow on the mound, too. He talked to players in the opposing dugouts and also to opposing batters, all in an effort to shake their concentration.

Despite leading the American League in walks and hit batters in 1950, Byrne won fifteen games for the pennant-winning Yankees and was selected to the All-Star team. On July 5, 1950, he hit four batters in the five innings he pitched, which tied an American League record for most batters hit in a game. He did not pitch as New York swept the Philadelphia Phillies in the World Series.

When Byrne came to work at Yankee Stadium on June 15, 1951, he found left-handed pitcher Stubby Overmire occupying his locker. Byrne was summoned to Stengel’s office and told he had been traded to the St. Louis Browns with $25,000 for Overmire.

Tommy did not fare well in St. Louis, winning eleven games while losing twenty-four during his year and a half with the club. “There was no greater tumble than going from the first-place Yankees to the last-place Browns,” Byrne said. But he enjoyed playing for the colorful Bill Veeck, who gave him a raise despite his 4-10 record for the tail-enders. Byrne tied another record for wildness on August 22, 1951, against Boston, when he walked sixteen batters in a game.

After posting a 7-14 record in 1952, the Browns traded Byrne to the Chicago White Sox with shortstop Joe DeMaestri for outfielder Hank Edwards and shortstop Willie Miranda. His tenure with the White Sox was brief, but he did have one shining moment. On May 16, White Sox manager Paul Richards summoned him from the bullpen to pinch-hit for infielder Vern Stephens with the bases loaded and two men out in the ninth inning. Right-handed pitcher Ewell Blackwell had just entered the game for New York.

Byrne recalled: “Richards asked me, ‘You ever hit this guy?’ ‘Yeah,’ I said, ‘about 11 years ago.’ ‘Well,’ said Richards, ‘How about going up and hitting one out of here?’ So I go up there and, after getting the count to 2-2, I don’t even remember swinging the bat, but I hit a line drive, 20 rows back in right field.” The grand slam won the game. During his career, Byrne batted .238 with 14 home runs, 98 RBIs, and a .378 slugging percentage.

Less than a month after the grand slam, Chicago sold Byrne to the Washington Senators. He appeared in six games for Washington in 1953, losing five, before being released on August 2 by owner Clark Griffith. “I had one day to go before becoming a 10-year man in the majors,” Byrne recalled. That annoyed him, but not as much as the reason Griffith gave for the move—they couldn’t understand what had happened to his hitting!

Byrne signed as a free agent with the White Sox, who sent him to the Charleston (West Virginia) Senators, their affiliate in the American Association. He was 1-6 with a 5.31 ERA for Charleston in the last two months of 1953. That December Chicago traded him to the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League for first baseman Gordon Goldsberry.

During the winter, Byrne played for a team in Pastora, Venezuela, where he began to experiment with changing speeds on his pitches. “I was determined to work on a slider down there, and it was amazing what I did in the short time there,” he said.

When the Rainiers’ newest addition joined the team in the spring of 1954, he picked up right where he left off in winter ball. The seasoned southpaw pitched great all year, keeping the Pacific Coast League hitters off balance with a variety of off-speed offerings and his recently developed slider. “It turned out to be the perfect spot for me,” Byrne said. “[Jerry] Priddy was a first-year manager and he needed a veteran pitcher who could give him innings. I was ready and willing. I needed starts on a regular basis to work on my contract.”

When the season ended, Tommy had compiled a record of 20 wins and 10 losses, and a 3.15 ERA. His 199 strikeouts led the league, and for the first time, outnumbered his walks (118). He also played in fifty games as an outfielder, first baseman, or pinch-hitter and hit for a .295 batting average, with seven home runs, and 39 RBIs.

Byrne’s statistics impressed an opposing manager, Oakland’s Charlie Dressen. When his old pal, Casey Stengel, sought his opinion on PCL players, Dressen told him, “The only guy here who can help you is Byrne. I suggest you get him. He’s a different pitcher than when I saw him with the Yankees. He’s learned what this is about.” On September 3, 1954, the Yankees purchased Byrne’s contract from Seattle. Byrne started five games for New York during the last month of the season, winning three and losing two.

By 1955 the Yankees pitching staff had been revamped, and Stengel made Byrne his number three starter behind Whitey Ford and Bob Turley.

At the age of thirty-five, Byrne set his career high for victories, finishing 16-5, with a 3.15 earned-run average. His .762 winning percentage was the best in the league, and the Yankees won the pennant. “He beat the other first-division clubs, Cleveland, the White Sox, the Red Sox, when it was them or us,” Stengel said. “Without him, we don’t win.”

Byrne started Game Two of the World Series against the Dodgers, in Yankee Stadium. He held them to five hits and two runs, and rapped a two-run single as the Yankees won, 4–2.

Stengel had enough faith in his veteran pitcher to give him the start in Game Seven. Byrne pitched 5 2/3 innings and gave up just two runs, but Johnny Podres shut out the Yankees as the Dodgers won the game, and the World Series. After the Series Byrne was part of the Yankees squad that toured Japan.

In 1956 the starting rotation was retooled with the additionof youngsters Johnny Kucks and Tom Sturdivant. Byrne made only eight starts and posted a 7-3 record with six saves. He made one relief appearance in the World Series, giving up a home run to Duke Snider in Game Two.

The 1957 campaign was Byrne’s last in the Major Leagues. He made four starts but did most of his work out of the bullpen. His last two mound appearances came in the World Series against the Milwaukee Braves. One of the outings was the occasion of a memorable incident.

The Yankees took a one-run lead in Game Four with a run in the top of the 10th inning. Byrne was summoned to save the game, and his first pitch to pinch-hitter Nippy Jones skidded past catcher Yogi Berra and rolled back to the stands. Jones insisted the ball had hit him on the foot, proving his point by showing a shoe-polish scuff mark on the baseball. Home-plate umpire Augie Donatelli awarded Jones first base. Byrne was replaced by Bob Grim, and the Braves won three batters later on a two-run homer by Eddie Mathews. Byrne said that if Berra had thrown the ball back to him instead of holding onto it for Donatelli, Byrne would have marked it up so that nobody could spot the shoe polish.

After appearing in a mop-up role in Game Seven, Byrne hung up his spikes for good. He was finding it harder to separate himself from the peaceful times and friendly people of Wake Forest. He’d gotten into the oil business, owned a couple of farms, and even opened a clothing store in Algiers, near Wake Forest. “When I sent back my contract after the ’57 season,” Byrne said, “the Yankees called me and asked me to come to St. Petersburg for spring training anyway.”

There, General Manager George Weiss offered him a new contract and a $5,000 raise, with a catch: it involved trading Byrne to the St. Louis Cardinals. “I told him, ‘You don’t understand, if I’m gonna pitch, the only place it’s gonna ever be is for the New York Yankees.’ ”

The hard-throwing left-hander ended his career in the majors with a lifetime record of 85 wins, 69 losses and a 4.11 earned run average. In eleven seasons with the Yankees he was 72-40 and a 3.93 ERA. At the plate he finished with 14 home runs and a very respectable .238 batting average.

A few years later Byrne became a scout for the New York Mets. In May 1963 he took over the manager’s job with the Mets’ Class A affiliate in Raleigh, North Carolina, and piloted the club for the remainder of the season.

Byrne retired from all baseball activities after the 1963 season. He had been living in Wake Forest during the off-season and now would make the college town his permanent home. His many business interests during this time included successful forays in real estate, a clothing store, farm equipment, and the oil industry. Byrne was also a dedicated civil servant: He served as a town commissioner, Bureau of Recreation chairman, and two terms as mayor of Wake Forest, from 1973 to 1987.

Byrne’s accomplishments on the ball field earned him induction into the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame, the Wake Forest College Hall of Fame, the Maryland Sports Hall of Fame, and the Baltimore City College Hall of Fame.

The town honored the former Yankee with two Tommy Byrne Days, in 1955 and 2007. He received numerous other accolades, including awards from the North Carolina governor and the Wake Forest Birthplace Society.

Byrne was a founding member of St. Catherine of Siena Catholic Church and a member of the Knights of Columbus. Beginning in 1957, the local high school gave an award in his name to the best athlete of the year.

Byrne died from congestive heart failure on December 20, 2007, at the age of eighty-seven. His wife of sixty-two years, Mary Susan (Nichols) Byrne, had died in 2002. Byrne was survived by three sons, Thomas, John, and Charles, and a daughter Susan, along with numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Byrne is buried in Wake Forest Cemetery.

Sources

All quotes are from Madden, Bill. Pride of October: To Be Young and a Yankee. New York: Warner Books, 2003.

Forker, Dom. The Men of Autumn. Dallas: Taylor Publishing, 1989.

Frommer, Harvey. New York City Baseball. New York: Macmillan, 1980.

Golenbock, Peter. Dynasty. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1975.

Halberstam, David. Summer of ’49. New York: Morrow, 1989.

Honig, Donald. The October Heroes. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1979.

Kahn, Roger. The Era: 1947-1957. New York: Houghton-Mifflin, 1993.

Lally, Richard. Bombers: An Oral History of the New York Yankees. New York: Three Rivers Press, 2002.

Madden, Bill. Pride of October: To Be Young and a Yankee. New York: Warner Books, 2003.

Rizzuto, Phil, and Tom Horton. The October Twelve: The Years of Yankee Glory, 1949-1953. New York: Forge, 1994.

Strauss, Frank. Dawn of a Dynasty. Lincoln, Nebraska: iUniverse, 2008.

Telephone interview with former professional baseball player Mike Kardash on February 5, 2010.

Telephone conversations between Thomas Bourke with Susan B. Gantt (Byrne’s daughter) on July 11, 2011, July 21, 2010, and August 15, 2011.

Anthony Salazar, former chairman of SABR’s Latino Committee.

John Benesch (information on Byrne’s 1953-54 season in Venezuela).

Ray Nemec (information on Byrne’s semipro career in North Carolina).

Frank Russo (information about Byrne playing in Oldtmers games at Yankee Stadium)

Baltimore Sun, December 23, 2007 (Tommy Byrne obituary)

Byrne obituary by Bryan Hoch, posted on thedeadballera.com.

Full Name

Thomas Joseph Byrne

Born

December 31, 1919 at Baltimore, MD (US)

Died

December 20, 2007 at Wake Forest, NC (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.