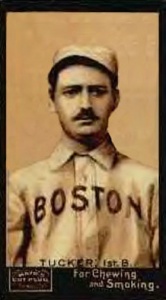

Tommy Tucker

Tommy Tucker’s career highlight came in 1889, when he hit .372, becoming the first switch-hitter to win a major league batting title. But scant attention was paid to such arcane matters then; he was a household name during his time not because of anything he accomplished on the diamond, but because a nursery rhyme bearing his name (Little Tommy Tucker) had yet to lapse into obscurity.

Tommy Tucker’s career highlight came in 1889, when he hit .372, becoming the first switch-hitter to win a major league batting title. But scant attention was paid to such arcane matters then; he was a household name during his time not because of anything he accomplished on the diamond, but because a nursery rhyme bearing his name (Little Tommy Tucker) had yet to lapse into obscurity.

Through the 1892 season, approximately the halfway mark in his career, the right-handed throwing first baseman owned a .297 composite batting average. The increased pitching distance the following year heightened batting averages across the board for the rest of the 1890s. In every case but one, position players at or near the midpoint of fairly lengthy big league careers increased their lifetime BAs after 1892, often by as many as 50 points, as was the case with Ed Delahanty. The lone exception was Tucker, who actually hit 13 points less, or just .284, in the second half of his major league sojourn. He finished at 290.

If his hitting decline were not burden enough, he also grew increasingly unpopular among fellow players with each passing year. His nicknames – “Foghorn”, “Noisy Tom” and “Tommy Talker” – provide an initial clue. By the time he took his last throw at first base in a major league game in 1899, few indeed were sorry to see him go.

Thomas Joseph Tucker was born in Holyoke, Massachusetts, on October 28, 1863. His parents were Patrick and Mary (née McMannis) Tucker, both of whom were born in Ireland. Tommy was the second of their six children. He was preceded by a sister named Delia and followed by John, Timothy, Rosa, and Joseph. Patrick Tucker, who worked in a cotton mill, died in an accident in 1874. As of the 1880 census, the four oldest children worked in a paper mill while their mother kept house. In all likelihood Tommy, as the eldest male child, went to work at that trade soon after his father’s untimely death and never finished school.

Tucker played for a semipro team representing his home town in 1882-83.1 He turned pro in 1884 with the Holyoke entry in the minor league Massachusetts State Association. He began the following season with Springfield of the Southern New England League before moving to Newark of the Eastern League. Returning to Newark in 1886, he hit .281 and was acclaimed the best all-around first baseman in the loop. Baltimore manager Billy Barnie fired weak-hitting Milt Scott (.481 OPS in 137 games in 1886) and replaced him with the fancy-fielding switch-hitter.

On November 23, 1886, in Holyoke, Tucker married Theresa Powers (whose parents also both came from Ireland). It’s notable that Tucker’s occupation was still listed as paper worker.

In his big-league debut on April 16, 1887, at Baltimore, the 5-foot-11-inch, 165-pound Tucker batted cleanup for the Orioles and went 1-for-3 while swinging from the left side in an 8-3 win over Philadelphia’s vaunted rookie right hander Ed Seward.2 He followed his outstanding rookie season in 1887 by leading the Orioles in home runs and RBIs in 1888, and then topped the American Association in batting in 1889.

Baltimore resigned its AA membership that fall and pirated most its players and team colors into the minor league Atlantic Association prior to the 1890 season. Tucker tied himself in knots, according to several items that winter in Sporting Life, and made himself look utterly foolish over whether to jump to the rebel Players League. He finally signed a personal services contract allowing Baltimore to sell him to any team he wanted, and wound up going to the Boston National League entry for $3,000.

Whether it was a change to the National League brand of ball or playing for a better caliber of team, he evolved almost immediately into a very different sort of player than he had been with Baltimore. Always an aggressive, in-your-face type – he led his league five times in being hit by pitches – he became downright fractious, perfecting a trick on wild pickoff throws to first base of falling heavily on top of the runner to prevent him from advancing. His language, particularly when he was acting as a base coach, grew increasingly vulgar and his off-field antics began putting him into frequent skirmishes with Boston manager Frank Selee. On September 21, 1893, Tucker showed up drunk for a game at Cincinnati but nonetheless insisted on playing. When Selee refused to put him in the lineup and wrote in Charlie Ganzel’s name at first base, Tucker verbally abused the manager to the extent that he finally had to be dragged out of the park by the police.3 That same season Tucker came under severe criticism from the Cleveland papers for his “dirty” play after Spiders catcher Chief Zimmer suffered a broken collarbone on July 12 when he tried to dive back into first base on a pickoff attempt, and Tucker blocked him off the bag with both knees.4

The following year, on May 15, 1894, at Boston’s South End Grounds, Tucker and Baltimore’s John McGraw helped launch the city’s “Great Roxbury Fire” when they got into a savage fight on the field in the third inning after Tucker slid hard into third base and McGraw kicked him in the face. Prior to the start of the inning, a group of boys had unwittingly set a small bonfire amid some rubbish beneath the right field stands. The conflagration in its initial stages could easily have been stomped out, but it was ignored by the crowd – who were caught up in the fracas on the field and its aftermath – until the end of the inning. By then the flames had reached such severity that they forced stoppage of the game and ultimately burned down not only most of the ballpark, but portions of over 200 buildings nearby, resulting in a loss “variously estimated at from $300,000 to $1,000,000” and leaving some 1,900 Bostonians homeless.5 The damage to South End Grounds was so extensive that the park was closed for 10 weeks while it underwent reconstruction; in the interim the Beaneaters played at Congress Street Grounds

Tucker’s most infamous moment in a road game also took place in 1894, at Philadelphia. On July 17, Boston tried in vain to delay a game during the eighth inning after Philadelphia had taken a prohibitive 12-2 lead. Boston had been ahead 2-1 at the end of the last fully played inning, the seventh, and wanted Umpire Bill Campbell to call the game because of the light rain that had begun falling before the eighth was completed. As per the rule, had Campbell done so the score would have reverted to the end of the seventh frame, and Boston would have won. After Philadelphia was able to circumvent Boston’s delaying tactics and end its turn at bat by having Sam Thompson purposely miss second base on his return to first on a long foul ball, Boston refused to continue and Campbell forfeited the game to Philadelphia. Soon after he did so, several fans, in the opinion of the Boston Globe, seemed to have had a “preconcerted plan to attack Tucker, for they fairly swarmed around this player” when he attempted to return to the Boston bench to retrieve a sweater he had forgotten. Reports conflict as to whether he sustained a broken cheekbone in the fracas or merely a severe bruise before Philadelphia players and police helped get him away from his assailants.6

Following years of trying unsuccessfully to trade his quarrelsome first baseman, Selee finally gave up hopes of obtaining a decent player in return and sold him to Washington for around $2,000 on June 3, 1897.7 Tucker seemingly thrived on the change of scene, hitting .338 for the D.C. club to post a composite .333 mark that season, his highest since winning the AA batting title eight years earlier. But Washington officials must have sensed that the revival was illusory, for they took a significant financial hit in order to get rid of Tucker. When they could not get waivers on him to send him to a minor league team, they sold him to Brooklyn on March 5, 1898, for $800.8 The 34-year-old first sacker lasted less than four months in Brooklyn before being peddled to last-place St. Louis on July 18.9 The Sporting News commented that Browns manager Tim Hurst “thinks well of Tucker, but many experts are of the opinion that Tom is on the downgrade and is but little if any above the minor league standard.”10 Yet, just a few months earlier, catcher Aleck Smith had said Tucker was “one of the greatest first basemen I ever saw. You don’t have to figure how you can get the ball in Tommie’s pocket. All you have to do is shut your eyes and bang away in the direction of first base any old way.”11

The next spring, when St. Louis and Cleveland consolidated under syndicate ownership, Tucker was shipped to the Forest City entry along with the rest of St. Louis’s dregs. He played in 1899 as if he were sleepwalking in between dodging all hard-hit balls that were sent his way (according to several sources), compiling an abominable .593 OPS and scoring just 40 runs in 127 games for the equally abominable Spiders. He was axed a full month before the season ended after he went 0-for-2 in an 8-2 loss to the Phillies’ Red Donahue at Philadelphia on September 13.12

Shunned by all remaining clubs when the National League lopped off four teams at the close of the 1899 season, Tucker spent 1900 batting a lackluster .277 for Springfield of the Eastern League. Following two more undistinguished seasons in the Connecticut State League, he left the game to work at his original trade in Holyoke paper mills.

At the time of his death in a hospital “after a long illness” on October 22, 1935, in Montague, Massachusetts, a town some 30 miles north of Holyoke, his son Raymond was a political journalist in Washington.13 Still, from all accounts, although Tucker had two successful children, and some of his grandchildren are alive today, life for him never had anywhere near the same flavor after he left baseball.

Tucker’s .372 mark in 1889 still stands as the season record for a switch-hitter. In addition he is #3 on the all-time hit-by-pitch list and held the record from 1893 to 1901 when Hughie Jennings passed him. An interesting task awaits future researchers: determining whether Tucker hit better from the left or right side of the plate. Most batsmen in the nineteenth century experimented at one time or another during their careers with switch-hitting, but few remained switch-hitters throughout. Tucker stands alone among 19th-century hitters with lengthy careers, not only in that his batting fell off markedly after the pitching distance was lengthened in 1893, but also because he apparently never tried to determine if he might have been better served by batting only from one side of the plate.

This biography is an expanded version of one that appeared in David Nemec’s “Major League Baseball Profiles: 1871-1900” (Bison Books, 2011) vol. 1.

Sources

In assembling this biography I made extensive use of the Boston Globe, Sporting Life, The Sporting News, the late David Ball’s groundbreaking nineteenth century Trade Log, David Funk’s blog “All Funked Up” and the Washington Post for details of Tucker’s professional baseball career. His family background came from ancestry.com.

Notes

1 New York Clipper , March 29, 1890.

2 Sporting Life, April 27, 1887, 2.

3 Boston Globe, September 22, 1893, 6. In the same game Cincinnati second baseman Bid McPhee wore a glove for the first time in his career.

4 Sporting Life, July 22, 1893

5 Sporting Life, May 19, 1894, 1; Boston Globe, May 16, 1894, 1; David Funk blog, “All Funked Up,” May 15, 2015.

6 David Nemec and Eric Miklich, Forfeits and Successfully Protested Major League Games (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2014), 78.

7 David Ball Trade Log

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 The Sporting News, July 23, 1898, 3.

11 Cincinnati Enquirer, May 24, 1898.

12 Boston Globe, September 14, 1899, 7

13 Sporting Life, April 27, 1887, 2.

Full Name

Thomas Joseph Tucker

Born

October 28, 1863 at Holyoke, MA (USA)

Died

October 22, 1935 at Montague, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.