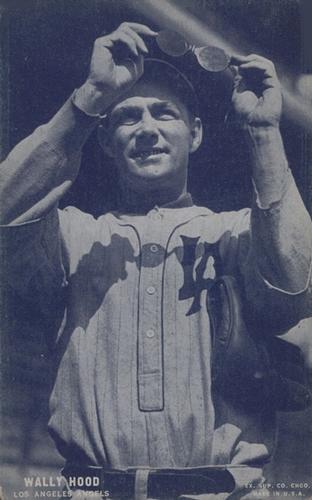

Wally Hood

Fred C. Newmeyer had “won another” game for his Bay City, Texas, baseball team in July of 1911.1 Through circumstance and personal motivation, Newmeyer would, after four years in professional baseball, begin and maintain a career in the motion-picture industry, rising from film extra to film director. In 1928, having worked with numerous silent film stars, including Harold Lloyd, he directed Paramount Studios’ “first feature with synchronized core and sound effects.”2 The film, titled Warming Up, reflected Newmeyer’s attachment to baseball and starred Richard Dix and Jean Arthur. To give credence to the film’s premise, plot, and action, he employed — in uncredited roles — professional baseball players from the Pacific Coast League. One of these players was Wally Hood.

Fred C. Newmeyer had “won another” game for his Bay City, Texas, baseball team in July of 1911.1 Through circumstance and personal motivation, Newmeyer would, after four years in professional baseball, begin and maintain a career in the motion-picture industry, rising from film extra to film director. In 1928, having worked with numerous silent film stars, including Harold Lloyd, he directed Paramount Studios’ “first feature with synchronized core and sound effects.”2 The film, titled Warming Up, reflected Newmeyer’s attachment to baseball and starred Richard Dix and Jean Arthur. To give credence to the film’s premise, plot, and action, he employed — in uncredited roles — professional baseball players from the Pacific Coast League. One of these players was Wally Hood.

Wallace James “Wally” Hood was born in Whittier, California, on February 9, 1895. His parents, James Gideon Hood, a butcher, and Catharine Ann (Moreland) Hood, both Canadian born, had settled in Whittier, where they married in 1892.3 Wally had three sisters, Catharine H., Vera I., and Minnie M. It appears that James and Catharine divorced between 1912 and 1914 and that each remarried.4 Catharine died, at age 64, in 1937. Identified as Catharine A. Pruitt, “A Pioneer of [the] City [Whittier], she had been struck by a motorcycle in Whittier. Police deemed the accident unavoidable.”5 James died in 1959 at age 80.

Wally attended public schools in Whittier, an early Quaker settlement named for poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier.6 Academically sound and athletically inclined, he served as vice president of the Whittier High School student body in 1912, his junior year, and president in 1913, his senior year. His yearbook notes that he participated in debate and oratorical contests.7 He captained the baseball and basketball teams, and participated in football and track and field. High-school baseball garnered attention in Whittier as a February 22, 1913, article in the Whittier News attests, referring to players and their positions, including “Ernie Chandler … backstop … [who] will attempt to hold Captain Wally Hood’s curves.”8 One of Wally’s nicknames in high school, “Jimmie,” appeared in a high-school annual publication praising his baseball abilities:

“Jimmie” Hood captained the team and started the season in the box “but threw his arm out” and was transferred to second base where he played a spectacular game, causing the failure of many attempts to steal second, and robbing batters of good hits. He batted .375 for the season.9

After high school, Wally ventured to Fullerton College. At Fullerton, about 12 miles southwest of Whittier, the right-handed pitcher-hitter earned the following praise, and a contract signing with the Pacific Coast League’s Vernon Tigers, in 1915:

Wally Hood, Fullerton’s pet pitcher, with the chrome vanadium steel arm and machine control, signed up with Vernon this afternoon. … Since Hood first pitched for the team July 11, he has won nine games and lost one at San Diego, average .900. His batting average to date is .350. 10

Hood’s stint with the Tigers was brief. As early as March of 1916 the Salt Lake Telegram noted that Vernon “has only 10 pitchers to cut down to six and Fairbanks, Hood and McElroy are pretty certain to be among the also rans.”11 The Vernon club did release Hood, but he was soon picked up by the Vancouver Beavers: Quoting a Western League writer, the Los Angeles Times wrote, “Wallace Hood, released by Vernon last spring and signed by Vancouver, seems to have the making of a star.”12 By May of 1916, Hood appears on the roster of the Beavers. However, and perhaps ironically, his name appears in a column stating, “The Tigers hit Hood all over the lot.”13 From late 1915 into early 1916, and when not playing baseball, Hood remained active on the roster of the Whittier Crescents, a basketball team in a new AAU league. As a forward, he became known as one of the “demon shot[s]” in the league.14

In 1917 the United States became embroiled in World War I. Driven by a sense of duty and responsibility, Hood applied, at the age of 22, for military service in the United States Aero Corps. His draft registration card, dated May 31, 1917, noted an exemption for him because his mother was dependent upon him. He was not called to duty immediately, which allowed him to rejoin the Vancouver Beavers.

For 1916 and 1917, Hood compiled a 12-win, 23-loss pitching record and a .243 batting average (Between pitching record and batting average, he had begun a shift to playing in the field.) In 1918 he was called to military service. In 1919, now primarily used as an outfielder, he returned to baseball, playing with two teams in two leagues. He joined the Moose Jaw Robin Hoods of the Western Canada League, appeared in 67 games, and hit .316. Although actual playing time with the Vancouver Beavers of the Northwest International League was limited, he did receive attention in the form of an on-the-field exposition. The president of the Beavers, Bob Brown, and “officials of the Aerial Club of Canada” devised a plan “whereby one of the aeroplanes of the league will fly over Atlantic Park … and will drop several baseballs … which Wally Hood … a commissioned flyer himself … will attempt to catch.”15 Whether or not Hood actually caught any of the dropped baseballs is unclear.

By 1920, Hood’s talent brought him to the major leagues. The 5-foot-11, 160-pound Hood, who threw and batted right-handed, made his major-league debut on April 15, 1920; his career would span three seasons, 1920-1922, with appearances on the rosters of two National League teams, the Brooklyn Robins and the Pittsburgh Pirates. Brooklyn placed him on waivers in late May, and the Pirates quickly claimed him to replace injured outfielder Carson Bigbee. However, when Bigbee returned to the field sooner than expected, the Pirates released him, and “Charley Ebbets instantly reclaimed the young outfielder.”16 Eventually he was sent to the Salt Lake City Bees of the Pacific Coast League. Before being shipped from Brooklyn to Pittsburgh, Hood played in a historic game — the 26-inning contest between the Robins and Boston Braves on May 1, the longest game by innings in major-league history. Hood went into the lineup after Hi Myers was injured. He got a single, a walk and a sacrifice hit in eight plate appearances and stole a base.

Hood performed very well with the Bees, appearing in 111 games, hitting .307 and maintaining a fielding (outfield) percentage of .962; he also pitched in one game with the Bees. After the 1920 season he and other players, including Sammy Bohne, Billy Cunningham, Eddie Ainsmith, and Les Nunamaker, traveled to Japan with a troupe assembled by Los Angeles sports promoter Gene Doyle. Hood’s passport application, dated September 30, 1920, had him leaving San Francisco on October 30, 1920, and his name appears on the passenger list of the ship Tenyo Maru, returning to San Francisco from Yokohama, Japan on February 21, 1921.17 He played two more seasons in the majors with the Robins, appearing in 56 games in 1921 and two games in 1922. Although a reliable outfielder, his .238 average would not be enough to keep him on the roster; he played his final major-league game on April 22, 1922. He finished the season with the Seattle Indians of the Pacific Coast League. On October 24, 1922, in Olympia, Washington, he married Edna Bernadine Rooks of Pullman, Washington. They had one child, Wallace James Jr. (The son pitched at the University of Southern California and was the first USC pitcher “to earn All-American first team acclaim. He was also a two time All-Conference first teamer.”18 Young Hood spent seven seasons in the minor leagues, mostly at the Triple-A level, and he pitched in two games with the New York Yankees in 1949. He was elected into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame in 2005.)

In 1923 the elder Hood joined the PCL’s Los Angeles Angels; that season, he was named the Angels’ Most Valuable Player, having batted a team high .340.19 He played with the Angels through the 1928 season. The final two years of his professional career, 1929 and 1930, saw him on the rosters of four teams: the Reading Keystones of the International League; the Seattle Indians of the PCL; the Memphis Chickasaws of the Southern Association; and finally, in 1930, the Sacramento Senators, of the PCL.

While with the Angels in 1928, Hood was one of several players (including Truck Hannah and Mike Ready) called upon to appear (in uncredited roles, appearing as themselves) in the Paramount Studios film Warming Up. Director Fred C. Newmeyer, a baseball player himself, knew that his film needed professional ballplayers to give a realistic vision of baseball. Released on July 25, 1928, the film starred Richard Dix and Jean Arthur. The film was Paramount’s first sound production. A reviewer declared: “You actually hear the crack of the bat, the call of the umpire, the roar of the crowd. …”20 Richard Dix studied the players and even emulated the superstitious behaviors of some. Hood was acknowledged for one of his superstitions: “ ‘Sure Fire’ is the laconic explanation of Wally Hood, formerly with the Brooklyn club and a member of the cast of ‘Warming Up,’ for his peculiar custom when two strikes are called against him of taking his chewing gum from his mouth and sticking it on the button on the top of his cap.”21

Hood appeared in three other films: Alibi Ike in 1935, The Stratton Story in 1949, and Rhubarb in 1951.

In Alibi Ike, a Warner Bros. film adapted from a Ring Lardner story, Joe E. Brown and Olivia de Havilland (in her first role) led a cast that included 26 ballplayers, among them Jim Thorpe. Whether or not any of these players had lines to speak, Joe E. Brown, an athlete with baseball experience, insisted that the film represent baseball faithfully.22 The New York Times reviewer wrote of the film: “Warners have fashioned a merry little film that will appeal first to the Brown enthusiasts, second to the Lardner disciples, third to the followers of the national sport and fourth to the rank and file of film-goers who think there is nothing like a harmless comedy to brighten the dull moments of a hot summer’s day.23

In 1935 Hood began a career as a PCL umpire. In his first month of umpiring, he earned praise: “Wally Hood, who used to be known as the ‘Whittier Walloper’ during his outfielding days, is coming along surprisingly well in his new role as umpire.”24 He quickly acquired a reputation which would serve him well at times. During an argument with a baserunner in a September 1935 game, the runner (Gene Desautels) shoved him. However, Mr. Hood refuses to be shoved around by a common ball player, so he called Desautels out again — this time out of the ball game.”25 His career, though, led him into numerous disagreements and confrontations, and not always pleasant critiques. For example, in 1939 a columnist wrote that Hood said, “If I were pitcher Larry Powell of the Seals, I’d give up throwing the screwball.” In response the columnist wrote: “If I were umpire Wally Good, I’d give up umpiring.— Almost any Pacific Coast League ball player.”26 By 1944 the PCL had seen enough and, after nine years as an umpire, league President Clarence Rowland included Hood among four umpires whose contracts were not renewed.

After losing his job, Hood worked as an electrician and was still called by filmmakers to appear in baseball-themed films. In 1949 he appeared in the MGM production of The Stratton Story, starring James Stewart and June Allyson. While some of the 72 ballplayers who worked in this film did have speaking roles — including Jimmy Dykes as team manager — Hood appeared as himself in an uncredited role.27 Among the ballplayers were Bill Dickey and Roy Partee. The film earned good reviews.

Hood’s final film role came in the 1951 Paramount film Rhubarb, starring Ray Milland and Jan Sterling. His film career ended as his professional career in baseball did– as an umpire. The film earned the following headline: “Rhubarb Rollicking Fun; All Runs, Hits, No Errors.”28 It was further noted that “most of Rhubarb was shot on the Paramount lot, with the baseball sequences lensed at Wrigley Field, home of the Los Angeles Angels in the Pacific Coast League.”29

Hood lived out the remainder of his life in the Los Angeles area. Records are not clear, but it appears that he had married twice. He was found by his ex-wife, Irene Cooke, collapsed in his apartment on May 2, 1965. A newspaper report read: “Wally Hood, Sr., a utility outfielder with the Brooklyn Dodgers [reports often refer to the Dodgers, not the Robins] in the early 1920s, was found dead in his apartment yesterday, his ex-wife reported.”30

Hood was 70. He is buried in Rose Hills Memorial Park in Whittier. In 2014 Hood was inducted into the PCL Hall of Fame.

This biography originally appeared in “From Spring Training to Screen Test: Baseball Players Turned Actors“ (SABR, 2018), edited by Rob Edelman and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 “Newmeyer Won Another,” Houston Post, July 8, 1911: 4.

2 “Richard Dix.” The Internet Movie Database. IMDB.com, Inc, n.d. Web. imdb.com/name/nm0228715/bio?ref_=nm_ov_bio_sm.

3 Catharine Hood’s name appears as both Catherine and Catharine.

4 “Town Is Dry. Charge Man Is Drunk,” Los Angeles Times, July 15, 1914: Part II, 12. After their divorce, Catharine later found work as a dressmaker, and James became an oil-field worker.

5 “A Pioneer of City Passes,” Whittier News, July 23, 1937: 2. Whittier Public Library Digital Archives. digi.cityofwhittier.org/awweb/main.jsp?flag=browse&smd=1&awdid=2g.

6 “About Us — A Short History,” City of Whittier, California. cityofwhittier.org/about/default.asp.

7 “Whittier High School Yearbook, 1913,” Whittier Historical Society, email communication.

8 Whittier News. February 22, 1913: 2.

9 “Baseball,” Cardinal and White, Whittier High School, 1913, 3. Whittier Historical Society, email communication.

10 “Pitcher Hood Has Signed Up With Vernon Team,” Santa Ana (California) Daily Register, December 27, 1915: 2.

11 “BEST CLUB,” Salt Lake Telegram, March 12, 1916: 13.

12 “Quite a Change,” Los Angeles Times, June 16, 1916: 23.

13 “At Vancouver Yesterday,” Tacoma Times, May 12, 1916: 6.

14 “Basket Teams After Blood,” Los Angeles Times, January 28, 1916: 22.

15 “Aeroplane at Athletic Park.” Vancouver (British Columbia) Daily News, May 16, 1919: 12.

16 “May Repurchase,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, December 17, 1921: 10.

17 “Wallace J. Hood, in the Passenger and Crew Lists, 1882-1959,” Ancestry.com.

18 “Memoriam Page,” USC Baseball Alumni. https://baseball.usclegacy.com/members/in-memorium, September 29, 2017.

19 “Wally” Hood: Pacific Coast League Content — Minor League Baseball.” https://milb.com/content/page.jsp?ymd=20140430&content_id=73836990&fext=.jsp&sid=l112&vkey=.

20 “‘Warming Up’ Great Picture,” Shreveport Times, September 23, 1928: 31.

21 “Ball Players Fear The Jinx,” Arizona Daily Star (Tucson), September 23, 1928: 16.

22 “26 Big Leaguers in Joe E. Brown’s ‘Alibi Ike’ Film,” Greenwood (Mississippi) Commonwealth, July 13, 1935: 6.

23 “The Screen; Joe E. Brown Returns in a Merry Film Version of Ring Lardner’s ‘Alibi Ike,’ at the Cameo,” New York Times, July 17, 1935. nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9407E2DB1E39E33ABC4F52DFB166838E629EDE. September 29, 2017.

24 “Wally Hood Making Good in Umpiring Role,” Los Angeles Times, April 3, 1935: 31.

25 “Desautels Chased,” Los Angeles Times, September 10, 1935: 28.

26 “Short, Short Story,” Oakland Tribune, July 6, 1939: 24.

27 “It’s a True Life Story,” The Sporting News, May 11, 1949: 13.

28 “‘Rhubarb’ Rollicking Fun; All Runs, Hits, No Errors,” Tampa Bay Times, October 8, 1951: 10.

29 “Ray Milland Co-Stars With a Cat in ‘Rhubarb,’” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 19, 1951: 30.

30 “Ex-Dodger Player Found Dead by Wife,” Louisville Courier-Journal, May 3, 1965: 28.

Full Name

Wallace James Hood

Born

February 9, 1895 at Whittier, CA (USA)

Died

May 2, 1965 at Hollywood, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.