Hilldale (Daisies) Club team ownership history

This article was written by Michael Haupert

This article was published in the Team Ownership History Project

1912 Hilldale Club. Back row: Bill Anderson, Alice Robinson, Lloyd Thompson, Marian Caulk, Devere Thompson, Mark Studevan, Clara Ivory, Ed Bolden, Helen Barrett, Charles Gaskins, Mary Ricketts, Hubert Jackson, Grace Ricketts, Sam Anderson and Leon Brice. Front row: Hulett Strothers, Raymond Garner, Billy Hill, Frank “Chink” Wilson, George Kemp, Hugh “Scrappy” Mason and Clarence Porter.

The Hilldale franchise of the Negro Leagues, often referred to as the Daisies, was formed as an amateur youth team in 1910, turned professional in 1917, and flourished for the next decade as one of the preeminent Black teams in the East. Hilldale’s fortunes sank with the economy in the 1930s, and despite attempts to revive the franchise, it was never able to regain its luster.

In the beginning

Austin D. Thompson, a 19-year-old ballplayer from Darby, Pennsylvania, organized the Hilldale Athletic Club in the spring of 1910. Hilldale was one of a number of Philadelphia-area amateur teams that competed against one another. Darby was an African-American enclave of 6,300 located five miles southwest of Philadelphia. Thompson started Hilldale on the road to prominence, but he was not around to see them reach it. By the end of the season he was gone, replaced by Ed Bolden, a volunteer scorekeeper for the team.

Thompson was barely older than the players on his team and did not foresee the true potential of his baseball club. Bolden, at 28, was also young, but was more mature and had much more business experience than Thompson. He also had a vision for the team, one that extended far beyond the confines of a local amateur club. As time would prove, he possessed unparalleled marketing skills. The combination of Thompson’s youth and Bolden’s experience led to the change in leadership.

Under his leadership, the club grew from a local amateur organization to a professional powerhouse. During his two decades in charge, Bolden built some of the best Black ballclubs in the East. From 1923 to 1928, he also presided over the Eastern Colored League (ECL), of which Hilldale was a charter member. All the while, he maintained a full-time position at the post office — a heavy workload that would eventually take its toll.

Bolden’s first substantial move after taking control of the club was to make aggressive use of the press to market the team. He began providing regular updates, including box scores, to the local Black press. He put up posters, mailed postcards announcing upcoming games, and purchased ads in the Philadelphia Tribune. He was so successful at raising the club’s profile that even the white press began reporting the scores of Hilldale games.1

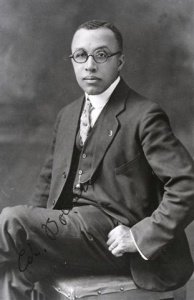

Ed Bolden

Edward W. Bolden2 was born in Concordville, Pennsylvania, on January 17, 1881. Before he began his career in baseball, he was a domestic servant and a clerk with the Philadelphia post office. At 5-feet-7 and barely 150 pounds, he was slight of stature, but exhibited a forceful presence. By the time he retired in 1946, he was an accomplished baseball executive and a 42-year veteran of the US Post Office. His post-office position was not a glamorous one, but it was prestigious for a Black man in the early twentieth century. In addition to his postal career, he found time to make a mark on the baseball world as an owner, officer in three different professional leagues,3 and one of the great hustlers in the history of the Negro Leagues.

Edward W. Bolden2 was born in Concordville, Pennsylvania, on January 17, 1881. Before he began his career in baseball, he was a domestic servant and a clerk with the Philadelphia post office. At 5-feet-7 and barely 150 pounds, he was slight of stature, but exhibited a forceful presence. By the time he retired in 1946, he was an accomplished baseball executive and a 42-year veteran of the US Post Office. His post-office position was not a glamorous one, but it was prestigious for a Black man in the early twentieth century. In addition to his postal career, he found time to make a mark on the baseball world as an owner, officer in three different professional leagues,3 and one of the great hustlers in the history of the Negro Leagues.

Bolden was a tireless and brash promoter, unafraid to play the race card. He heavily marketed the fact that Hilldale was Black-owned. It paid off, playing a role in the team’s ability to land top-quality talent and schedule attractive opponents. It also made him a local hero of sorts in Darby. But while he promoted Hilldale as a “race institution,” he was not afraid to do business with white businessmen when he found it profitable.

Bolden earned a reputation as a clean, upstanding owner with little tolerance for rowdiness or umpire baiting. He advocated “clean ball” and gentlemanly behavior on the field and expected the same from the fans in the stands. Once he even went so far as to press charges against patrons of his own ballpark for rowdy behavior. This incident led to his employment of security guards at home games to ensure the safety and comfort of the players, umpires, and fans.4

The heavy toll of presiding over a team and a league, while at the same time holding down a full-time job, would eventually take a toll on Bolden’s personal life and his postal career. He suffered a nervous breakdown in 1927, temporarily forcing him out of baseball.

In 1932 he took charge of a new team, the Philadelphia Stars. It caused a great deal of controversy because he partnered with white booking agent Eddie Gottlieb. Bolden retained an ownership share in the Stars until his death in 1950, adding a stint as commissioner of the Negro National League for the 1936 season, to boot. His death “ended an era in race baseball and the attempt on the part of its pioneers and successors to elevate it to a big time level.”5

Darby Field

Perhaps Bolden’s greatest stroke of marketing genius was the construction in 1914 of a ballpark, known as Darby Field, or Hilldale Park. Because Hilldale did not have the capital to self-finance or borrow the funds necessary to build a ballpark in its entirety, it had to do it with annual improvements out of the operating budget. As a result, the ballpark was a modest and continual work in progress. It was a wooden ballpark, originally featuring bleacher seating for only a few thousand. Over time, it grew in size and stature, adding a grandstand and concessions, among other modifications.6 The location of the park was convenient for the team’s fan base, but Bolden was not content with that. He assured that the park would also be easy to reach by arranging with the local streetcar company to have a line run straight to his ballpark, adding extra cars during games.

Darby, with its low transportation costs to major Black baseball hubs in New York, Baltimore, and Washington, made Hilldale an attractive destination for all the top teams on the East Coast. Hilldale’s ownership of its own ballpark eliminated the problems of finding quality dates and negotiating profitable lease terms for stadiums owned by white businessmen. Bolden combined these advantages with his marketing skills, ensuring the financial success of the Hilldale franchise.

Hilldale earned additional income by leasing the ballpark beginning in 1917. That same year the club also began to sell advertising in the ballpark, in part to pay bonuses to big-name players like Spottswood Poles and Otto Briggs, who presumably were bigger draws than the likes of George Johnson, Nap Cummings, or McKinley Downs, regulars on early Hilldale rosters. In 1920 Bolden secured a lease on a second ballpark, in Camden, New Jersey, expanding his market, and securing a site for Sunday games, thereby skirting Pennsylvania’s blue laws.

Going Pro

The year 1916 proved to be a watershed year for Hilldale. The team implemented several substantial operational changes before the season. Players were required to be present for twice-weekly practices and mandatory pregame workouts and to abstain from alcohol. Fines of $5 were threatened for violation of any of these requirements. Insubordination was punishable by expulsion from the roster. The ballpark was upgraded, a grandstand was built, admission was fixed at 20 cents, new uniforms were ordered, and regular weekly meetings were held during the offseason. The biggest change occurred after the season.

Hilldale had been organized into a for-profit cooperative in 1914. It operated as a semipro team for three seasons before incorporating in January of 1917 as the Hilldale Baseball and Exhibition Company, a fully professional squad. Ed Bolden was elected president by his co-owners,7 who referred to themselves as the “old fellows,” since most of them had been with the team since its early amateur days but were now too old to play.

On October 15, 1916, the “old fellows” dissolved the old town team and transformed the franchise into a fully professional team. They left their share of the profits in the treasury while the “new fellows,” i.e. the young players, were paid their shares and discharged. No longer would the team be run as a co-op with the players sharing in the proceeds at season’s end. Instead, players would be employees of the “old fellows.” A week later they laid out a plan to incorporate with capital of $10,000.8 The incorporation was finalized in January of 1917. In order to cover the costs of running a professional team, admissions were increased by a nickel that season.

The decision to turn professional was a profitable one, made possible by good management and shrewd marketing on the part of Bolden.9 Unlike a major-league team, Black ballclubs, especially before the formation of formal professional leagues, had to write their own schedules, and quite often had to lease ballparks in which to play.

Hilldale was particularly aggressive in marketing and in its pursuit of complementary sources of income. The club sold the standard peanuts and soft drinks, eventually expanding to add ice cream and cigarettes in 1917. Itemized expenditures on game days are also listed for straws and ice. Enticing customers with cold drinks was one way to attract fans on a sweltering summer day in Philadelphia. Another clever marketing approach was used to get around the Sunday blue laws by admitting fans to the ballpark free, provided they purchased a program. The programs were generally profitable for the club, since they sold advertising to cover the printing costs.10 This ruse frequently ran afoul of local law enforcement but became a moot point with the purchase of the Camden ballpark in 1920.

One of Bolden’s more curious publicity stunts was a fundraising scheme he concocted in 1914. In order to raise cash for the team, he held a raffle offering a ton of coal as first prize. The effort succeeded, and the team ended its first professional season with $226.01 in the bank.11 As a co-operative club, Hilldale’s financial accounts were approved by the audit committee, which was made up of a subset of the players. At the conclusion of each season, the audit committee would decide how to divide the remaining revenue.

Otto Briggs and Spottswood Poles became the first salaried players for Hilldale, in 1917. Briggs was paid $273 for the season and Poles earned $448. Prior to Briggs and Poles, players were paid a share of the gate. Briggs was a Hilldale mainstay, sticking with the team for the next 13 seasons. This is no small issue, since unlike their major-league brethren, Black professionals were not bound by a reserve clause, even when they were part of an organized league.

The decision by Hilldale to turn professional was financially risky but paid off immediately both on the field (23-15-1 record) and off ($1,916 profit). Their profits that year were more than the previous three years combined. The bottom line was helped by several postseason exhibitions that Bolden lined up against major leaguers. To beef up the squad for these games, he added stars Smokey Joe Williams, Louis Santop, and Dick Lundy to the lineup. Santop would remain with the team for several seasons, and was instrumental in leading Hilldale to the first colored World Series in 1924.

Bolden’s success inevitably drew the attention of white New York agent Nat Strong, who controlled the East Coast booking market for Black teams, and coveted Hilldale for his agency. When his advances were rebuffed, Strong threatened to drive Hilldale out of business by locating a competing team across the street from Darby Field. Bolden responded promptly and publicly to this threat by taking out an ad in the Philadelphia Tribune to state his case:

“The race people of Philadelphia and vicinity are proud to proclaim Hilldale the biggest thing in the baseball world owned, fostered, and controlled by race men. … We are proud to be in a position to give Darby citizens the most beautiful park in Delaware County, a team that is second to none and playing the best attractions available. To affiliate ourselves with other than race men would be a mark against our name that could never be eradicated.”12

Bolden’s public-relations coup and his skills at signing top talent defused Strong’s threat and contributed to the rise of Hilldale to the top of the Eastern colored circuits. His refusal to ally with white baseball men won him praise and admiration, enhancing his stature in the Darby community. Years later, after he left Hilldale, his reversal of this belief would cost him in the court of public opinion.

Hilldale’s profits dipped in 1918, but the club managed to stay in the black. After World War I Bolden and other local promoters began to challenge Philadelphia’s blue laws prohibiting commercialized ball on Sunday. They banded together in an organization known as the Allied Athletic Association. Their bid ultimately failed, but it begat another organization, the Philadelphia Baseball Association, which would provide Bolden with valuable administrative experience, and demonstrate his standing in the local baseball community. The PBA was formally organized in February 1922. Besides campaigning for Sunday ball, it also addressed player jumping, umpiring, gambling, and discipline problems. Hilldale was a member of the PBA, and Bolden was the only African-American elected to its Board of Governors.13

Another example of Bolden’s creativity was his adaptive method of meeting the payroll. Initially players were paid out of the proceeds of each game. Good players, however, demanded more security, so he began paying them on a monthly basis.14 Along with regular monthly salaries came the scheduling of a greater number of games, which meant increased travel and a host of additional details that needed to be coordinated, increasing the front-office demands for the team, and necessitating additional hiring.15

Hilldale used a cash-basis accounting system. This presents two significant problems in evaluating the club’s financial status. First, it rarely identified the specific sources of revenue, which were primarily tickets and concessions, but on occasion included donations, capital injections, and rental income from the ballpark. Second, the club was not always explicit about why certain individuals were paid. It is fairly easy to determine who the players were, but a host of other names appear on the payroll. In later years names were often replaced with job titles, and by comparing amounts we can make some educated guesses as to who was the mascot and who were the security guards and ballboys, but it was more difficult to separate out the gatekeepers, ticket sellers, groundskeepers, and public-address announcer. We can tell that the club was financially successful, but the details are sometimes cloudy.16

The good news for the reliability of the Hilldale financial data presented is that the amounts involved are small, so our inability to account for them in detail is only a technical problem. As an example, in 1917 Hilldale spent $107 on “carpentry and scoreboard” expenditures. Technically, that amount should be capitalized and depreciated over the period that it benefits. But the amount is small compared with the profits of almost $2,000, so that being technically correct is not critical.17

On a cash basis, profit is reflected as an increase in cash, while a loss would be a decrease in cash. In other words, a profitable year was measured by the change in the year-end bank account balance. Reporting profit as the change in cash was justified for Hilldale because it had very limited assets. It had a modest ballpark with a wooden grandstand, which it leased on occasion, so a cash basis worked fine for that item because the cash payment was the expense.

The Rube Foster feud18

As he would continue to do throughout his career, Bolden improved the Hilldale roster by signing players away from other squads. When Hilldale was an amateur team, he recruited players from other sandlot teams, sometimes advertising in the papers for open tryouts, or placing classified ads seeking specific players.19 In later years he signed players from other teams, often earning the enmity of other owners as a result. This practice led to his long-running public feud with Rube Foster.

The feud had its roots in the organization of the Negro National League (NNL) by Foster in 1920. The league suffered from many problems, ranging from a lack of competitive balance to poor publicity. Foster considered contract jumpers one of the greatest threats to league stability. He was particularly upset with Bolden, whom he accused of stealing three of his players after the 1919 season. In retaliation, Foster pledged his support to the Madison Stars and Bacharach Giants, competing clubs in the East. The Giants joined the NNL and immediately raided the Hilldale roster.

Bolden responded to the raid with a legal challenge, which he ultimately dropped when he could not afford to continue the proceedings. He claimed that none of the players he had signed away from Foster’s club had been under contract at the time, nor were they protected by a reserve clause; hence he had not been guilty of enticing anyone to jump his contract. Bolden’s eventual creation of a competitor league to the NNL only further strained the relationship between the two entrepreneurs.

League ball

Hilldale abandoned the life of an independent team when it paid $500 for an associate membership in the National Association of Colored Professional Baseball Clubs (NACPBC) for the 1920 season. The advantage of joining a league was a regular slate of games and a central authority. Unfortunately, the ability of the league to discipline either the players or the clubs was practically nonexistent. Teams regularly bypassed scheduled league games when the prospect of a more profitable exhibition game presented itself. In between scheduled games, they would play almost any team that would agree to terms on price and location. That year more than two-thirds of the Hilldale schedule was against nonleague opponents. Even when it joined the much better organized Eastern Colored League in 1923, Hilldale frequently scheduled lucrative nonleague exhibition contests to boost the bottom line. The scheduling of these exhibition games was necessary for the financial survival of Black ballclubs.

Before joining a league, a typical game day for Hilldale began with a trip to the bank. The treasurer withdrew enough money to make all the expected payments associated with each game. At the conclusion of the game, everyone (the opposition, the workers, and in the early days before guaranteed salaries, even the Hilldale players) was paid in cash. The day’s receipts were then deposited in the bank. If the balance at the end of the day exceeded that at the beginning, it was a profitable venture. Salaried players and front-office staff were expensed, so a share of the game receipts was set aside to cover these and other budgeted expenses.

In December of 1920 Hilldale left the NACPBC and joined Rube Foster’s Negro National League (NNL) as an associate member for a $1,000 deposit. The membership provided protection from player raids by other league members. The following year Bolden made one of his most lucrative investments, purchasing the contract of Judy Johnson from the Madison Stars for $100. Johnson became a fixture in the Hilldale lineup for the next decade, leading the team with a .341 average during the 1924 colored World Series and managing the team in 1931 and 1932. In 1975 Johnson was elected to the Hall of Fame.

By 1922 Hilldale was no longer satisfied with its membership in the NNL. While it was protected from player raids, it had to give up lucrative dates against Eastern clubs on Rube Foster’s outlaw list. Foster maintained a list of teams that did not honor NNL contracts and forbade league members from playing them. He felt that by denying these outlaws lucrative dates against the high-quality teams of the NNL he would punish them at the box office. Unfortunately for Hilldale, it suffered as well.

The travel costs associated with league play were another sore point. Only four Western teams came to Darby Field for games, and Hilldale’s Western trip was a financial loss. Bolden sought to withdraw the team from the league and requested a refund of his deposit. Foster refused, Bolden blustered, and tempers flared. The two threatened to raid each other’s rosters in what would have been a debilitating battle. In the end, Bolden backed down, and Hilldale retained its associate membership in the league for a second season.

Hilldale’s records show a stunning loss of $3,366 in 1922. What makes it stunning is that it was the only year the club recorded a loss from the time it incorporated in 1917 until their final season of 1932. It is impossible to determine exactly what happened because the financial records for the second half of the year are missing. The 1922 season was shaping up to be another profitable one for Hilldale through July 22, when the records end. When they resume on January 1, 1923, the closing statement reflects the $3,366 loss with no indication as to what transpired in between.20

The end of the season was usually a very profitable period for the team because of the Labor Day weekend and the lucrative postseason exhibition games against barnstorming white teams. It is possible that Hilldale put some of its money into more ballpark improvements. Since Hilldale operated on a cash basis, these improvements would have been expensed in their entirety in 1922. Or perhaps the club purchased player contracts or a team bus, distributed cash to owners, or simply had a run of bad luck. Only the latter would suggest that the club was truly unprofitable for the year.

After the 1922 season, Hilldale resigned from the NNL for the second time. Foster still refused to refund Hilldale’s deposit, citing a recent change in league bylaws preventing it. Foster’s refusal to refund the deposit was a symptom of the mistrust the two executives still had for one another.

Bolden struck back by forming a rival league, the Mutual Association of Eastern Colored Baseball Clubs, popularly known as the Eastern Colored League (ECL), set to begin play in 1923. Unlike the NNL, which was governed by Foster, the ECL had no president, but was run by a commission composed of one representative from each club. Bolden was elected chairman of the commission.21

The formation of the league set off a public-relations war with Foster and the other members of the NNL. Their chief criticism was that some of the owners of ECL teams were white. Of particular concern to Foster was Bolden’s inclusion of Nat Strong, the white booking agent in New York. From Bolden’s perspective, Strong’s tight control of the New York market made it necessary to do business with him, especially since Sunday ball was still prohibited in Philadelphia, but was allowed in New York. Bolden countered that most of the NNL teams rented parks from white owners and rent on these parks ran as high as 25 percent of gross receipts. In contrast, several of the ECL parks were controlled by Black owners.

In his typical fashion, Bolden strengthened his team by raiding NNL rosters, resulting in Hilldale dominating the early years of the league. It won the first three ECL titles, appeared in the first two Colored World Series (in 1924 and 1925), and won the Series in 1925. Of course, raiding rosters did not enhance his popularity with NNL owners.

Foster’s NNL and Bolden’s ECL maintained frosty relations throughout the 1923 season and into 1924. But in September of that year, the two executives met in New York and put their differences aside, agreeing to stage a colored World Series and “respect the sanctity of their inter-relationship” between the two leagues.22 Essentially, this meant they were willing to put their personal feud aside in order to make money, but it also laid the groundwork for more substantial cooperation between the leagues.

After the series, Bolden and Foster authored a National Agreement, which was ratified by the two leagues. The agreement divided geographic territory between the two leagues, standardized player contracts, and formally inserted a reserve clause into player contracts.23 Both Bolden and Foster felt the agreement would provide the stability necessary to ensure the financial success of the leagues.

The NNL champion Kansas City Monarchs bested Hilldale in the inaugural World Series. While a financial success, the player shares were less than they likely would have earned in a barnstorming series against white players.24 Attendance did not meet expectations, drawing barely 45,000 for the 10-game series. Despite the disappointing attendance, Bolden and Foster were happy with the outcome because the series helped to focus national attention on professional Black baseball. Unlike regular-season games, the series was acknowledged by the white press in many cities.

Hilldale won the second colored World Series in 1925, but it was a financial disaster. Attendance averaged fewer than 3,000 per game for the six-game series, and Hilldale’s winning share was barely $80 per player.25 Unlike the previous season, all series games were played in the hometowns of the two participating teams.

After the season, Bolden made a number of player moves, few of which paid dividends, and the fortunes of the team sank in 1926 both on the field and at the box office. As a result, the Darby community turned on Bolden for the first time, blaming him for mismanaging the roster.26

The heavy toll of presiding over a team and a league, while at the same time holding down a full-time job eventually took a toll on Bolden’s personal life and his postal career. He suffered a nervous breakdown as the 1927 season came to a close, leading to his resignation from both league and team leadership positions. Vice President Charles Freeman replaced him as president of Hilldale. His absence was short-lived. By the end of February 1928 he regained the Hilldale presidency.

The Black economy had already slipped into a recession, well ahead of the general economy. With finances tight, Bolden made more roster adjustments. Then he made his big move, withdrawing Hilldale from the ECL. Although he had founded the league, by 1928 he no longer found membership profitable, arguing that the team had lost $18,000 in potential revenues in 1927 and could do better as an independent team.27 Two other teams also withdrew before Opening Day, dealing a mortal blow to the league, which did not finish the season. Hilldale went 15-12 that year as an independent team, and while attendance at Darby Field fell for the second year in a row, it still averaged a respectable 1,100 fans per game.

Just one year later. Bolden changed his mind again about league membership. He assembled five of the six original ECL franchises and formed the American Negro League (ANL) in time for the 1929 season. The league lasted only one season, during which Hilldale compiled a 39-35 record, good for fourth place. Bolden bore the brunt of the criticism from the fans. During his now annual roster tinkering, he waived several popular players, and by the time the 1929 season opened he had only four players remaining from the 1925 championship roster.

The 1929 club was the highest-salaried in Hilldale’s history, featuring future Hall of Famers Oscar Charleston, Martin Dihigo, Biz Mackey, and Judy Johnson. Each of them earned more than $900 for the season, with Dihigo and Charleston leading the way at $1,600 apiece. While these salaries may sound low, it was quite good for a Black man, especially considering that the average manufacturing wage in the United States that year was $1,500. And that salary was earned over 12 months, while the players earned their salaries in only six months.

The year 1929 marked the apex of Hilldale’s popularity. Despite its mediocre record and high payroll, it sold more than 56,000 tickets and turned a profit. Storm clouds were on the horizon, however. Jobs were disappearing and the economy was plunging into what would become the Great Depression, wreaking financial havoc on Black baseball.

In response to the difficult times faced by the high-salaried Hilldale franchise, Bolden attempted to dissolve the corporation early in 1930. He quietly made plans for a new team he planned to organize with the financial backing of white promoter Harry Passon. The rest of Hilldale’s board had other ideas, however. They blocked his attempt and bought him out of the corporation. Just like that, Ed Bolden was no longer a part of the legacy he had created.

Hilldale’s demise

John Drew, a Black politician who earned his fortune operating a successful bus line in Philadelphia, ran the Hilldale club after Bolden’s ouster. His refusal to deal with white booking agents made it difficult to line up quality opponents in 1930 and 1931 when there was no organized Black league in the East. In 1930 he was able to schedule only 22 home games, which drew an average of 650 fans, barely half the crowd Hilldale averaged the previous four seasons. The 1931 season was not much better. Despite a gaudy 42-13 record, the fans stayed away. Hilldale averaged 840 fans a game and drew fewer than 100 paid admissions on three occasions.

In a desperate attempt to survive, Drew spent $14,000 refurbishing Darby Field, and Hilldale joined the newly formed East West League for the 1932 season. Sadly, it was all for naught. Neither the league nor the franchise was able to weather the worsening economy, and both disbanded in July of 1932. Hilldale had played to a 27-17 record under the guidance of manager Judy Johnson, but the depressed economy simply could not support the team. Hilldale sold fewer than 50 tickets eight times in 20 home games.

Hilldale’s misfortunes were exemplified by the change in its method of paying players. It went from fixed salaries averaging $750 a season in 1929 to sharing the gate in 1932. In the waning days of its existence, the team played games in which its share of the gate was less than $100. After paying expenses, the players were sometimes left with only a couple of dollars apiece.

United States Baseball League

Hilldale disappeared from the baseball scene for more than a decade before making one final, brief appearance. It was slated to be a member of the United States Baseball League, a phantom league Branch Rickey created in 1945 to cover his true intent to scout Black players for the majors. The league barely survived its inaugural season and did not make it through the 1946 season.

The United States Baseball League (USL) initially had six clubs, one of them the Philadelphia Daisies. After failing to secure a lease on Shibe Park or another suitable local venue, the team leased Island Park in Harrisburg. In an attempt to increase interest in the team, it was renamed the Hilldale Daisies, but did not play at Darby Field. Before the season started, Rickey transferred the Hilldale franchise to Brooklyn and renamed it the Brown Dodgers, under the control of Joseph W. Hall, one of the two owners of the Hilldale franchise. The other owner, Robert J. “Whitey” Mazzer, organized a new Hilldale franchise for the league. The USL was a disaster. Hilldale seldom played a home game, played poorly at that, and dissolved by midseason. Only four teams completed the season.

It was an ignominious ending for a once proud franchise. Hilldale stood atop the Eastern Black baseball world for more than a decade after turning professional. Ed Bolden turned a successful amateur team into a powerful and profitable professional one, captured a national championship, and saw five future Hall of Famers wear the Hilldale flannels.28

MICHAEL HAUPERT is Professor of Economics at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse and co-chair of the SABR Business of Baseball Committee.

Sources

Cash-Thompson Archives, African American Museum, Philadelphia.

Haupert, Michael. “Ed Bolden: Black Baseball’s Great Modernist,” Black Ball 5, no. 2 (Fall 2012a): 61-72.

Haupert, Michael. “Ed Bolden,” SABR Baseball Biography Project, sabr.org/bioproj/person/84ab3bca. (2012b).

Haupert, Michael, and Ken Winter. “The Old Fellows and the Colonels: Innovation and Survival in Integrated Baseball,” Black Ball 1, no. 1 (spring 2008): 79-92.

Hogan, Lawrence D. Shades of Glory (Washington: National Geographic, 2006. Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994).

Lanctot, Neil. Fair Dealing and Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1910-1932 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1994).

Lomax, Michael E. Black Baseball Entrepreneurs 1902-1931: The Negro National and Eastern Colored Leagues (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2014).

Philadelphia Independent, October 7, 1950.

Philadelphia Inquirer, August 2, 1914.

Smith, Courtney Michelle. Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2017).

Photo credits

1912 Hilldale Club: Larry Lester / NoirTech Research

Ed Bolden: National Baseball Hall of Fame Library

Notes

1 The first such mention occurred in the Philadelphia Inquirer on August 2, 1914: 48.

2 This section is based on Haupert 2012a and 2012b. For a book-length biography of Bolden, see Smith.

3 The Eastern Colored League, the American Negro League, and the second iteration of the Negro National League.

4 Hogan, 142.

5 Roscoe Coleman, sports editor, Philadelphia Independent, October 7, 1950.

6 For example, in 1915 the Hilldale ledger records $117.73 spent on lumber for grandstand, building permit, carpentry work, nails, wire for outfield fence and backstop, and paint. In 1917 an additional $754.29 was allocated for lumber, labor, and hardware, for further expansion of the grandstand.

7 William Anderson, Charles Freeman, Thomas Jenkins, George Kemp Jr., George Mayo, Mark Studevan, and Lloyd Thompson were the other owners. There is no indication in the minutes or financial records what financial stake each of the owners had in the ballclub.

8 Cash-Thompson archives. There is no indication how many shares were intended to be sold, nor even whether this capital was ever collected from the owners.

9 For a more in-depth analysis of the business of the Hilldale franchise, see Haupert and Winter.

10 Cash-Thompson Archives.

11 Cash-Thompson Archives.

12 Hogan, 67.

13 Lanctot, 68.

14 As early as August of 1915 Bolden recognized the value of differential pay for players. That month the team owners voted to devote the proceeds of one game solely to the two pitchers. Cash-Thompson Archives.

15 In 1921 eight individuals received payments of $375 for “service,” including team President Bolden. Of the seven who received the same compensation as Bolden, six had been with Hilldale during all five professional years, and before that as players. In short, it appears that Hilldale had developed a management team, headed by Ed Bolden. Cash-Thompson Archives.

16 While the financial records are a fabulous resource, the cash-basis method of accounting used by Hilldale is lacking in some details of great interest. We know, for example, that Hilldale earned $8 in stadium rental income in 1917, but the records do not indicate to whom the field was leased that year or any other year.

17 The problem with using a cash basis as an accounting system is borne primarily by the historian. Because only cash flow is measured, there is insufficient information in the existing records to allow separation of field maintenance expenditures from investment in the field. There are lots of instances of the club buying materials and paying workers. Most of the time there is not enough detail to tell if they were preparing the field for that day’s game or building something to be used over several years. In other words, were these operational expenditures, or investments in capital that should be amortized over several years?

18 For a detailed discussion of this feud, see Lomax.

19 Lanctot, 22.

20 Cash-Thompson Archives.

21 Lanctot, 93.

22 Lanctot, 110.

23 Lanctot, 130.

24 Seventeen Hilldale players took home the losers’ share of $3,285 to split, or $193 each. Sixteen Kansas City players shared $4,927 or $308 each. Cash-Thompson Archives.

25 Cash-Thompson Archives.

26 Lanctot, 146.

27 Bolden’s lament hardly seems reasonable. An additional $18,000 in revenues would have been an increase of 42 percent over their best year on record. And when they did play as an independent team in 1928, their home ticket sales actually decreased by 5 percent. Hilldale financial records do not indicate road receipts for either 1927 or 1928, but for those years when road receipts are available, they never exceeded home receipts, so it is unlikely Hilldale would have made up that $18,000 amount on the road.

28 In addition to the aforementioned Judy Johnson, other Hilldale players who have been elected to the Hall of Fame include Martin Dihigo, Louis Santop, Biz Mackey, and Oscar Charleston. Another Hall of Famer, Smokey Joe Williams, joined Hilldale for a series of exhibition contests after the 1917 season.