The Hernandez Brothers: Livan and Orlando

This article was written by Peter C. Bjarkman

“I know what everyone knows: Cuba is the worst place on the globe to be an athlete today. But I’m sure I know something even stranger. It is also the best.” — S.L. Price, Pitching Around Fidel

Cuban “defectors” have been one of the biggest MLB stories of the early twenty-first century and the immediate impact on big-league diamonds of the likes of Aroldis Chapman (2010), Yoenis Céspedes (2012), Yasiel Puig (2013), José Abreu (2014), and Aledmys Díaz (2016) have elevated interest in the island nation’s communist baseball enterprise to an all-time high.1 The compelling rags-to-riches tales of these escapees from the reported restrictions of Fidel Castro’s realm seemingly provide dramatic feel-good sagas guaranteed to appeal to the bulk of flag-waving American fans. Big-league boosters in Los Angeles, Chicago, Oakland, New York, and elsewhere across the Organized Baseball map have loudly welcomed the stunning splashes made by a small handful of stellar Cuban players on their favored hometown teams. They have in large part also cheered the apparent blows struck at the demonized Castro regime in the waning days of a half-century-old Cold War standoff that has kept Cuban baseball mostly off the radar for five decades. But what we find on closer examination is also a saga with a truly ugly underbelly — one threatening the integrity of big-league operations almost as much as it is decimating the sport in one of its most tenacious international outposts. And the phenomenon of Cuban player defections is also a story with more misconceptions attached than perhaps any other headline-grabbing event involving the North American national pastime.

A vexing problem with most of the media stories surrounding Cuban baseball defectors — such as “El Duque” Hernández and José Contreras (a pair of ace pitchers who both ended up starring for the Yankees, and also teamed to bring Chicago its first world championship in nearly a century) or more recently Puig, or Céspedes, or Abreu — is that in many if not most cases the stark truths have been embellished by enthusiastic journalists and hyperbolic player agents. For the journalist there were scoops to be found and newsprint to be sold; for the agent, high stakes attached to the player’s promised MLB payday. El Duque’s desperate December 1997 “freedom flight” from Cuban shores on a makeshift leaky raft was later exposed by intrepid Sports Illustrated writers (November 1998) to be a heavily fictionalized version of precisely how manipulative agent Joe Cubas had arranged and carried out the star pitcher’s clandestine removal from his homeland and onto the lucrative MLB free-agent market.2 Defector stories have also heavily distorted the true picture of baseball talent on the island of Cuba, forestalling any fully accurate portrait of the modern-era Cuban League as a legitimate alternative baseball universe.

For an American press corps devoted to the capitalist free-enterprise economic and political model, the expanding story of Cuban athletes abandoning a socialist sports structure fits all too perfectly into the deeply-imbedded Horatio Alger Myth — the classic American success story and archetypal American character arc with its pilgrim’s progress from rags to riches. It is the replaying (in this case with an enriching anti-communist political overlay) of the search for the true American Dream. And the American Dream by almost anyone’s reading always equates directly to the search for untold American dollars.

Not surprisingly, the saga of “El Duque” Hernández and his hair-raising escape from unjust Cuban oppression thus reads exactly like an expected Hollywood script. There were, indeed, suggestions during the ballplaying fugitive’s earliest months in the States that film rights to the adventure, with its heartwarming overtones of a desperate search for the Great American Success Story, were actually being marketed to Hollywood producers. It had all the elements of a masterful drama after all, one designed to sell well all across Middle America. There was the unjust INDER (Cuban sports ministry) suspension that took away a star ballplayer’s rights to his livelihood in Cuba. Then the staged show trial by the Castro government that transformed the former national hero into a shunned pariah and social exile. There was the thrilling escape by a handful of refugees who somehow survived shark-infested waters and a dangerous marooning without food or water on an isolated cay in the Straits of Florida. Add an unlikely fortuitous rescue by the US Coast Guard. And for extra drama there was also a true knight in shining armor who appeared on the scene in the form of crusading ballplayer agent Joe Cubas, who was able to head off possible deportation back to Cuba. Finally comes a fittingly climactic dreamlike big-league season with the anointed “America’s Team” — the storybook New York Yankees — and a full dose of 1998 World Series heroics thrown in for good measure.

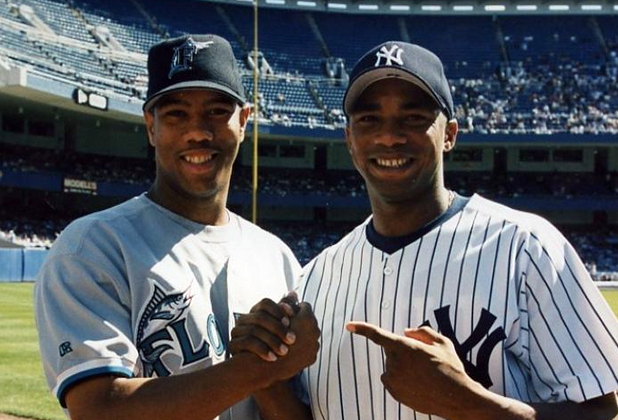

The Cuba defectors saga certainly does not begin with Orlando Hernández. His half-brother Liván perhaps represents a more legitimate launching pad for events representing initial leaks in the Cuban League system that so long remained isolated and protected from the clutches of Organized Baseball’s expansionist agendas. It was also Liván’s flight from Cuba and eventual big-league heroics in Miami that set the stage for the eerily parallel saga of El Duque. The beginnings of the tale emerge with the onset of the 1990s and trace their roots to a daring escape at the Miami airport by one of the island’s top stars of the 1980s. When national team ace René Arocha decided to abandon a Cuban squad in the midst of the late-summer 1991 USA-Cuba Friendly Series, his departure sent considerable shockwaves through the Cuban baseball establishment.3 Arocha’s surprise decision to leave his native land behind overlapped with the budding career of Cuban-American player agent Joe Cubas and played no small role in inspiring a novel “Joe Cubas Plan” for exploiting the earliest cracks in Cuba’s hold on its wealth of native talent. That plan — simple in design and ingenious in conception — amounted to getting promising players off the island by whatever means possible, establishing a third-country residence to avoid both a big-league free agent draft system and US Treasury Department Cuba embargo restrictions, and then peddling the Cuban refugees to the highest big-league bidders. With this plan in place, an obsessively anti-Castro Cubas could strike severe blows at the regime that once exiled his parents from Havana, while also filling his own pockets with boatloads of cash.

Cubas initially played a large role in the escapes of two prominent Cuban pitching mainstays who preceded the Hernández brothers out of Cuba. Ozzie Fernández (Osvaldo Fernández Rodríguez) followed the path of René Arocha when he also bolted from the Cuban camp in Millington, Tennessee, on the eve of the July 1995 USA-Cuba Friendly Series. The big right-hander was an ace for the Holguín National Series team and a member of the 1992 Cuban squad that had earned gold at the first official Olympic baseball tournament in Barcelona. Fernández was sharing a hotel room with catcher Alberto Hernández, a Holguín teammate, at the time he elected to bolt with Cubas. The flight would turn out to be a most unfortunate circumstance for the young backstop, who would later be condemned alongside El Duque and star shortstop Germán Mesa in the government ballplayer smuggling trial of Cubas’s cousin Juan Ignacio Hernández Nodar, and would subsequently accompany Duque in his own fateful December 1997 flight to Anguilla Cay. Cubas and pitcher Fernández had apparently been discussing the possible escape plan for some time during furtive meetings at past tournament events, and there had also been reported meetings on Cuban soil between the pitcher and Cubas’s silent partner, a Cape Cod real estate speculator named Tom Cronin. Once Fernández fled Millington, Joe Cubas quickly spirited him away to the Dominican Republic with formal plans already made to enter him into the big-league free agent market.4

Osvaldo Fernández’s departure came only days before tireless agent Cubas received a surprise phone call from Mexico indicating that young prospect Liván was also ready to jump a Cuban delegation that was training in Monterrey. What was at first a trickle was now becoming a steady stream from which Cubas was positioning himself as the major beneficiary. An even bigger loss for the Cubans would unfold during the next USA-Cuba Series a year later when another ace, Rolando Arrojo, walked out of team quarters at the Albany (Georgia) Quality Inn.5 Again, it all had been orchestrated by Cubas, including a secretive smuggling operation that had already spirited the pitcher’s family (a wife and two young sons) out of Cuba. Coming on the eve of the Atlanta Olympic Games, Arrojo’s stunning defection would result in a lengthy suspension of the USA-Cuba Friendly Series, which was not re-established until almost two decades later.

If the first successes for Cubas came with the enticements of veteran island aces Fernández and Arrojo — if only from the standpoint of their impact on the domestic Cuban League scene back in Havana — his biggest haul would inevitably be Liván Hernández, not yet a top star at home yet nonetheless a highly touted prospect and likely a future national team mainstay. It was the escape and latter exploits of Liván in Miami that also subsequently launched the convoluted tale of El Duque’s fall from grace at home and eventual abandonment of the Cuban system that had given birth to his talents.

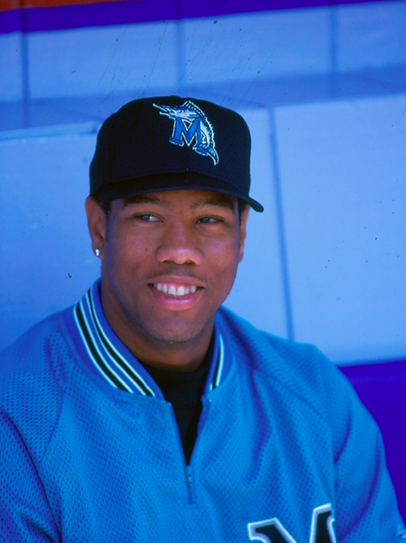

Liván was still a developing prospect with only a trio of National Series seasons under his belt when he departed Cuba. Although already a privileged member of the national team pitching staff when he fled in Mexico from the select squad preparing for a late-October Intercontinental Cup event on tap for Havana, he was still barely 20 years of age. He had won but 27 league games with the Isla de la Juventud team and thus his promising career was barely under way on his home island.

The younger Hernández was also a far different type of pitcher from his equally successful and at the time more celebrated elder brother. Simply put, he was a pure natural with a hopping fastball and smooth delivery that would be the envy of any pro prospect and was certainly the dream of any pro scout. Duque had worked hard to develop and polish his art by the time he enjoyed his first successes with the Industriales team in the mid-’80s; he had possessed neither the speed on his pitches nor the same smoothness and effortlessness of delivery. Liván, by contrast, found that it all came easy — too easy in the eyes of some. What he displayed in natural gifts he notably lacked in self-discipline. Coaches and the sporting press early and loudly complained about the degree to which Liván was seemingly squandering his immense talents.6

There had been precious little contact between the half-brothers over the years while they grew up on different corners of the island; Liván was in fact already 10 when they first met. Duque was born to a different mother (Maria Julia Pedroso, Arnaldo’s first wife) a decade earlier (October 11, 1965); he had already logged a half-dozen National Series seasons by the time Liván made his rookie debut with the Isla team. Liván was born in same Villa Clara Province (February 20, 1975) as his elder half-brother (to Miriam Carreras, third of four women with whom Arnaldo Hernández fathered children), but had moved to the isolated special territory of Isla de la Juventud (Isle of Youth) as a youngster when his ballplaying father served a brief stint there as a manager and pitching coach. But the two brothers would see each other occasionally in the late 1980s and the relationship was always quite warm despite the wide differences in age, circumstances, and personalities.

Liván became frustrated with his hardscrabble Cuban life earlier than El Duque, who at least lived in the more stimulating surroundings of the capital city. There might be a number of explanations for why Liván choose defection as early as he did. Steve Fainaru reports on one theory that the final spur was perhaps an incident involving a missing television tube.7 But Fainaru also observes that this was likely no more than a symbolic element in the larger drama. Life was especially hard for a ballplayer marooned in Isla, even by the standards of Cuba’s “Special Period” of deprivation in the early ’90s. Liván himself would eventually speak eloquently during the ESPN 30 for 30 documentary filming of “Brothers in Exile” about his ultimate reasons for leaving. It mostly had to do with the repressive treatment of Cuban players by their own state security and repeated bans on carrying home even simple items like hotel toiletries. Demands to remain ideologically pure by sacrificing oneself for the revolution’s notion of idealized sport were increasingly difficult to stomach as family members went without even the most basic necessities on the home front.

Liván, for all his talent, would have major problems adjusting to life in the United States. With a lucrative Florida Marlins contract in hand ($4.5 million secured by Cubas) he quickly found his new life packed with challenges of a far different order. A youngster who had known only poverty and who had developed little in the way of self-discipline was suddenly thrown into a land of plenty with seemingly unlimited personal resources at his command. He gorged himself on fast food, especially McDonald’s hamburgers. He reportedly bought a fancy new sports car every three months of his first year on American soil. And the extravagance almost ruined his budding career and squandered his hard-won opportunity before it even got off the ground. Liván overnight ballooned in size and seemed to lose the edge on his natural fastball. The Marlins brass watched helplessly while his promising future careened toward inevitable self-destruction. During his initial minor-league season with Double-A Portland and Triple-A Charlotte, the super-talented but now out-of-control Cuban phenom had become a major reclamation plan for his immediate handlers and for the entire Florida Marlins franchise.

Nevertheless, reclamation efforts won out. Slimmed down enough to finally again be effective, and clearly rededicated to his nearly lost pitching craft, Liván enjoyed a truly sensational summer as a 1997 Marlins rookie. He reeled off a midsummer victory skein that grabbed headline attention around the country. In the process he played a major role in lifting his newly minted National League team to its first-ever division title and postseason appearance. The regular-season performance (a 9-3 ledger) was not enough in the end to garner senior circuit Rookie of the Year honors, but it was more than enough to capture hearts in Miami. The Cuban exile community at long last had its own hometown hero among the recent waves of defectors striking a blow at the despised Castro government. This one was not pitching in St. Louis (like Arocha), Oakland (like Ariel Prieto), San Francisco (like Osvaldo Fernández), or nearby Tampa Bay (like Arrojo one year later), but right here in front of his fellow exiled countrymen a stone’s toss from Miami’s Little Havana.

Postseason heroics would cap the phenomenal 1997 debut National League season for the first Cuban in decades to play a significant role in a major-league pennant race. To kick things off, there was an MVP performance in the National League Championship Series. Liván claimed the NLCS opener in Atlanta with three scoreless relief innings. Then, as an emergency starter in crucial Game Five, the Cuban novice authored a complete-game, three-hit, 15-strikeout masterpiece. Two more effective outings earned a second MVP trophy during the historic World Series triumph over Cleveland. Despite early-inning struggles, Liván outlasted veteran Orel Hershiser in the opener, the first World Series game ever played in the state of Florida. And in the Game Five rematch with Hershiser, Hernández again was more gritty than brilliant while barely holding on down the stretch to win, 8-7, with some nail-biting ninth-inning relief help from closer Ron Nen.

It would be the first World Series success for a still young Miami franchise, and one made extra special for hordes of Cuban exiles by the heroics of one of their very own. The aftermath of a Game Seven extra-inning, Series-clinching win erupted in a spontaneous love feast for both Miami’s Cuban community and its own newly adopted hero. In a surprise good-will gesture, a baseball-loving Fidel had allowed Liván’s mother, Miriam Carreras, to travel to Miami for the Series finale. Flushed with the victory and the unexpected family reunion, Liván would raise his MVP trophy high overhead before a national TV audience and shout into the microphone in heavily accented English the words that would make video newsreels around the nation. “I love you, Miami!” It had to be a painful moment indeed for any INDER officials who might later catch a video glimpse of that Miami celebration scene and hear those potently defiant words.

A Second Brother in Exile

The remarkable story of El Duque Hernández actually begins with the tale of his father Arnaldo, a failed erstwhile star in the Cuban League during its earlier decades.8 Arnaldo’s spotty career provides a most interesting narrative in and of itself. Fainaru’s incisive portraits in The Duke of Havana make it altogether clear that one simply can’t know the latter El Duque’s early life in Cuba without grasping the background story of a colorful father and a pair of equally talented ballplaying brothers. Arnaldo — the father and the original “El Duque” — had himself been a considerable baseball talent in his youth. But a domestic-league career never went far for the less-than-serious Arnaldo Sr., and his subsequent years would produce a vagabond lifestyle that would convert a potential pitching phenom into a living legend of a very different order. The elder Arnaldo fathered two future ballplayers (Arnaldo Jr. and Orlando) with his first wife and then another, Liván, during a second marriage. He would spend decades as an apparently carefree drifter enjoying his aura of irresponsibility and passing briefly in and out of his equally famed children’s lives. Fainaru tracked him down in 1999, now residing in the central province of Las Tunas with yet another son and still all too eager to reminisce about a squandered youth and boast that his youngest offspring — 15-year-old Marlon — was most likely now also destined to become the true supreme pitching talent of his rather star-crossed family (an idle dream, since Marlon would never pursue a ballplaying career).

The remarkable story of El Duque Hernández actually begins with the tale of his father Arnaldo, a failed erstwhile star in the Cuban League during its earlier decades.8 Arnaldo’s spotty career provides a most interesting narrative in and of itself. Fainaru’s incisive portraits in The Duke of Havana make it altogether clear that one simply can’t know the latter El Duque’s early life in Cuba without grasping the background story of a colorful father and a pair of equally talented ballplaying brothers. Arnaldo — the father and the original “El Duque” — had himself been a considerable baseball talent in his youth. But a domestic-league career never went far for the less-than-serious Arnaldo Sr., and his subsequent years would produce a vagabond lifestyle that would convert a potential pitching phenom into a living legend of a very different order. The elder Arnaldo fathered two future ballplayers (Arnaldo Jr. and Orlando) with his first wife and then another, Liván, during a second marriage. He would spend decades as an apparently carefree drifter enjoying his aura of irresponsibility and passing briefly in and out of his equally famed children’s lives. Fainaru tracked him down in 1999, now residing in the central province of Las Tunas with yet another son and still all too eager to reminisce about a squandered youth and boast that his youngest offspring — 15-year-old Marlon — was most likely now also destined to become the true supreme pitching talent of his rather star-crossed family (an idle dream, since Marlon would never pursue a ballplaying career).

Arnaldo’s eldest son and namesake, Orlando’s senior by two years, was occasionally reported to be the most gifted athlete of the clan. But an accident with a machete during teenage years had scarred his wrist and robbed his fastball. When a second son came along, the proud patriarch also wanted to name him in his own image (a third Arnaldo), but, bowing to his wife’s objections, settled on a close approximate, Arnoldo. Family legend (reported by Fainaru) claims that the headstrong Arnoldo as a preteen himself insisted on rearranging the letters to Orlando. Arnaldo Jr., his pitching career sidetracked and sabotaged by the childhood injury, eventually would find his way into the National Series for a single modest season as a first baseman with Havana’s second league team, Metropolitanos. He was desperately trying to resurrect the pieces of a broken baseball dream when in April 1994 he was tragically struck down by a fatal aneurysm only a few months after turning 30. The family’s poverty at the height of Cuba’s Special Period clearly contributed to the untimely death. The lack of a family phone, available gasoline and electricity, and a nearby ambulance all conspired to delay medical assistance that might have saved Arnaldo’s life. Orlando was totally devastated by the tragic death of his idolized older brother.

Orlando would ironically prove to be the lesser natural talent among Arnaldo’s three ballplaying offspring, outshone in early years not only by Arnaldo Jr. but also later surpassed in raw talent by the late-arriving Liván. Orlando’s arduous path to the National Series was anything but an avenue paved with immediate successes. He was exposed to the sport as a toddler, watching his father and later his more promising elder brother play. His mother, María Julia, would regularly drag her two sons to Latin American Stadium to watch the original El Duque pitch, even though the marriage had already been dissolved. Baseball was in the youngster’s blood from the start. But when he tried out for the provincial EIDE (elementary level) sports academy at age 11, he was promptly rejected and told he had little aptitude for the sport. Undeterred, he plugged on with the encouragement and occasional schooling of an uncle who had also played during early National Series years as a spunky shortstop of limited skills. Through constant application, Duque had developed enough promise by the age of 16 to be accepted into a high-school-level sports academy (ESPA). He finally debuted at age 21 with the Havana Industriales, the team his father had once briefly played for. It was not a particularly young age for a Cuban League rookie when compared to some of the island’s more precocious stars. And it would then be another half-dozen seasons before Orlando would truly blossom as a recognized pitching ace.

By the mid-1990s, Duque had finally carved out his niche as one of the most talented and idolized pitchers on the island. A first season of double-figure wins came in 1992-93 (12-3) and was followed by stellar 11-2 and 11-1 ledgers. He enjoyed an especially heated rivalry with future defector Rolando Arrojo (then starring for a Villa Clara team in the process of posting three straight league titles) and also with Industriales teammate Lázaro Valle. By the time of the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, both Valle and Duque were mainstays on a potent Team Cuba staff. And on the domestic front, after 10 full seasons Duque had compiled the best won-lost record (126-47, .728) in island league history. The mark remained his lasting legacy in his abandoned but never forgotten homeland.

Duque’s troubles began with Liván’s September 1995 Mexican defection, an event unfortunately overlapping with the flight of Fernández, who also skipped out on the Cuban team during a July exhibition series in Millington, Tennessee. Paranoia about such defections was suddenly growing by leaps and bounds in the Cuban camp. Not surprisingly, El Duque was placed under immediate surveillance, since his own possible defection was apparently widely suspected within the INDER inner circles. But the fallout harassment wouldn’t stop there. In March 1996 he was dropped from Team Cuba’s roster for the coming Atlanta Olympics, a severe personal blow made more painful by the fact that the star pitcher received the news only via a TV broadcast announcing team selections. Talented shortstop Germán Mesa (a defensive genius often compared to Ozzie Smith) had also been suspected of defection plans and was also booted from the Olympic squad headed for Atlanta. Mesa’s exclusion would unexpectedly open the career door for another talented shortstop, Eduardo Paret, who was destined to eventually become captain of Team Cuba throughout the entire first decade of the new millennium.9

If Liván’s defection haunted his half-brother, Cubas’s indirect efforts at further infiltration of the Cuban baseball establishment would soon prove far more deadly. Juan Ignacio Hernández Nodar now entered the scene and things got much worse in a hurry. Juan Ignacio had once worked closely with his cousin Joe Cubas but there had been a bitter falling-out, spawned mainly by Nodar’s refusal to follow his cousin’s edicts against traveling openly to Cuba. In the aftermath, Juan Ignacio decided to set himself up in the ballplayer agent business with a particular focus, of course, on Cuban defectors, since that is where the big bucks could most quickly be found by a novice hoping to crack the agent business. Juan Ignacio stepped up his travels to Cuba but was not the smoothest of operators. He flaunted his presence on the scene by flashing wads of cash and making bold public display of his lavish lifestyle. Cuban state security rapidly had him on its radar and he was soon arrested at a youth tournament in Sancti Spíritus. It quickly came to light that he was carrying a number of false documents and an illegitimate passport with El Duque’s name on it. The already disgraced pitcher — along perhaps with stellar shortstop Mesa — was the big fish Nodar Hernández was hoping to land.

Onetime Joe Cubas associate Tom Cronin, now Juan Ignacio’s full-fledged partner, had just landed in Havana at the time of Juan Ignacio’s arrest and was also immediately taken into custody, then quickly sent packing back to the United States. But consequences would be far worse for others caught up in the web. The subsequent Hernández Nodar trial (opening on October 28, 1996) was pure disaster for El Duque, Mesa, and national team catcher Alberto Hernández. (Alberto had seemingly come under suspicion when his roommate, Ozzie Fernández, fled the Cuban camp in Millington.) All were called to testify and it was a grueling and frightening experience. El Duque was first up and stoically refused to brand Juan Ignacio a dangerous smuggler rather than merely a casual friend; Mesa, by contrast, pointed his finger at the American as an enemy of the Cuban state. A terrified Alberto evasively answered questions about his own past contacts with Cubas during overseas trips. Hernández Nodar was promptly convicted and sentenced to prison for 13 years, a term he would serve out in full.10 His crime had apparently been his plotting to carry out illegal defections (those of El Duque, Mesa, Alberto, and possibly ace pitcher Pedro Luis Lazo), but the truth was that he was being punished as much for the actual defections previously orchestrated by his now estranged cousin Joe Cubas as for any of his own bumbling activities.

There were several smoking guns in the Hernández Nodar affair that led to the downfall of the three Cuban players. The wannabe agent had become the link that allowed Liván to aid his impoverished brother back in Havana with gifts of much-needed cash. Nodar on several occasions had carried large bundles of American dollars not only to Duque but also to Liván’s mother, Miriam Carreras, still living in Isla. And he did so with little discretion or even minimal caution. Fainaru later quoted Duque’s own claims about just how foolhardy and careless his benefactor had been. Worse still, Nodar had foolishly decided he could pry both Duque and Mesa away from Cuba with a scheme that was more James Bond than Joe Cubas in its outlines. And so, on his final ill-fated visit, he carried with him forged Venezuelan work visas in the names of both ballplayers that he thought would facilitate his efforts. Such documents are highly illegal in Cuba, as they are in just about any country. In the end that was the evidence that sealed his own fate as well as theirs.

And then in the wake of the trial, the biggest blow of all came when Duque and Mesa were summoned to the Latin American Stadium’s INDER offices for an ominous high-level meeting. They optimistically expected they might perhaps receive some stern warnings about future behavior and perhaps be left home during a coming scheduled tour of Mexico by their Industriales team. But instead both, along with Holguín catcher Alberto Hernández, were informed that they were now being banned for life from Cuban baseball. The “Pride of Holguín” (Alberto) would return home to his own embarrassment and disgrace that included the dismantling of a shrine at the local ballpark displaying his hard-earned trophies and gold medals. Germán, suspected by many of cooperating at the trial to secure his own hoped-for pardon, disappeared into a quiet obscurity from which he wouldn’t reappear for two years. But it was the star Industriales pitcher — condemned in the wake of his brother’s heresy — who suffered the most severe banishment consequences.

El Duque was now effectively a shunned man in the city where only months before he had been an unrivaled sporting hero and national icon. The sport he loved had been stripped away from him. He could play ball only in a weekend recreational league where, because of his skills, he was not allowed to pitch and had to play the infield in a treasured souvenir New York Yankees T-shirt. His failing marriage to Norma Manzo quickly dissolved. He was assigned to work as a physical therapist at the psychiatric hospital in his neighborhood near Havana’s José Martí International Airport. Life seemed to have hit rock bottom.

Duque’s escape from Cuban shores on Christmas weekend of 1997 was a secretive and deftly plotted affair largely orchestrated by his close friend Osmany Lorenzo. The group would include new girlfriend Noris Bosch, Lorenzo himself, all-star catcher Alberto Hernández, and several fellow travelers including boat pilot Juan Carlos Romero.11 After several reportedly harrowing (but apparently not life-threatening) hours, the group successfully reached Anguilla Cay. But the trip became surprisingly complicated when a prearranged pickup launch promised by Duque’s great uncle Ocilio Cruz never arrived from Miami as anticipated. After three tense days filled with fears of being hopelessly lost or perhaps fatally marooned, the frightened and hungry refugee group was eventually located by an American patrol helicopter, then loaded onto a Miami-based Coast Guard cutter and finally delivered to authorities in the Bahamas.12 That is when the real complications set in.

It appeared for a time that the refugees might be sent back to Cuba. It was at that crucial juncture that opportunist Joe Cubas (alerted to Duque’s plight and also grasping his own sudden opportunity to cash in) arrived on the scene. It is reported in some accounts (including the ESPN documentary) that a US visa had already been arranged for the highly valuable baseball pitcher (along with his girlfriend and catcher Alberto Hernández). According to those versions, Duque nobly refused to leave the Bahamian refugee encampment without his entire contingent of companions. (As Fainaru eventually unfolds the tale, that selfless decision to deny a US visa would have negative consequences in the future when it came to seeking Washington aid in arranging transport of Duque’s mother and daughters out of Havana on the eve of a 1998 World Series victory celebration.) Cubas in the end was able to arrange the transfer of all members of the party to Costa Rica, where they would eventually receive the required third-country residence visas.

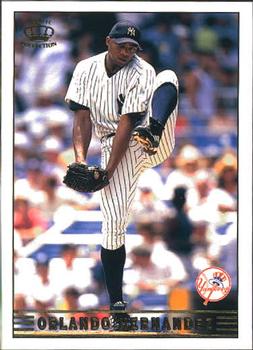

Within six months, Cubas had arranged a deal with the Yankees, who had missed out on brother Liván three years earlier, and by late spring Duque was already proving his skills at Triple-A Columbus. The Yankees contract was not what Cubas had hoped for but was substantial enough: $6.6 million for four years with a $1 million signing bonus. In short order the 32-year-old rookie reached New York for his big-league debut, a five-hit, seven-inning victorious effort against the Tampa Bay Devil Rays. One colorful rookie-season incident that has become legend has Hernández questioned by New York media about the pressures of first facing the Red Sox and Pedro Martínez in “The House That Ruth Built.” (It would have been the game of September 14, in which Duque tossed a three-hit shutout.) El Duque is reported to have laughed off the question by responding that no pressure could compare to what he had already known pitching against rival Santiago de Cuba with 50,000 fanatics crammed into Havana’s Latin American Stadium.

Duque wasted little time in nearly matching Liván’s own first-year postseason heroics. And this time it would happen on a grander stage in baseball’s anointed media capital of New York City. The Cuban import posted a dozen rookie victories (against four losses), emerging overnight one of the aces of a deep Yankees staff. He then authored several crucial victories in a postseason charge to the American League pennant. None was more vital than a brilliant seven-inning shutout effort during a do-or-die Game Four ALCS victory over the Indians at Cleveland’s Jacobs Field. In his single World Series outing, Hernández breezed to a 9-3 victory as the Yankees easily dispatched the San Diego Padres with a four-game sweep. The dream season was crowned by the most personally important moment of all when El Duque was tearfully reunited with his mother and two daughters just in time for the traditional New York City victory tickertape parade.

That emotional family reunion provides one of the strangest twists of the entire Duque Hernández saga. Orlando had been deeply depressed over the 10-month separation from his daughters (8-year-old Yahumara and the younger Steffi), a deep void that could never be filled by glories of newfound freedom or any headline achievement on the big-league diamonds in the United States. Through the heroic behind-the-scenes labor of Joe Cubas’s personal aide René Guim (pronounced Gimm with a silent U) and City University of New York international relations professor Pamela Falk, efforts had been mounted to convince Fidel Castro that it might serve his own interests to make yet another goodwill gesture and allow Duque’s family to freely and quickly leave Cuba. Such action would repeat a concession Fidel had made only a year earlier by releasing Liván’s mother to join her son for a World Series celebration in Miami.

Fainaru (The Duke of Havana, Chapter 17) again provides an elaborate account of the reunion efforts and their eventual happy outcome, and it was that event, played out on a private airstrip in New Jersey, that provides a feel-good conclusion for Mario Díaz’s 2014 ESPN documentary film. Cardinal John O’Connor, the archbishop of New York, would be a main player in the unfolding events, along with his emissary, Mario Parades, who personally carried the cardinal’s letter of request to Fidel. The pivotal heroine had been the tireless Pamela Falk, who first enlisted the cardinal’s aid and then fought to convince initially uncooperative Clinton administration officials to provide the needed US visas. Joe Cubas and George Steinbrenner — two men not especially celebrated for their altruism or humanitarian gestures — also played significant roles in the unfolding drama. Cubas had originally initiated the entire plot to bring his star client’s missing family to US shores and at the eleventh hour it was also Cubas who enlisted aid from the Yankees owner in the form of a private jet needed to rush the new arrivals from Miami to New York for the time-sensitive reunion.

Fidel’s gesture was a lone bright spot when it came to the Cuban government’s role precipitating and then following El Duque’s fall from grace in Havana and his eventual resurrection in the US big leagues. Duque had been treated by INDER officials and the communist government mechanism with what can only now be viewed as a fully unwarranted savagery. He and Mesa and Alberto Hernández were stripped of their small livelihoods, their much larger prestige, and blossoming careers, as well as their valued reputations as loyal Cubans, for no crime that they had actually committed, but rather for some imagined infraction that paranoid officials believed they might have considered committing. They in fact were not in the end convicted of any specific crime against either the state or its baseball machinery. They were instead the ill-fated recipients of a merely symbolic act. They had been held up to the public as examples of suspected (even if not actual) disloyalty in what was quite transparently a desperate and irrational government effort to stem the tide of a growing annoyance that no one had the slightest solution for.

In retrospect, one might in some respects understand and even sympathize with the frustrations of INDER officials and perhaps of Fidel himself as they witnessed what from their perspective was an illegal and immoral effort to destroy their national sport for the mere profit of outsiders — intruders they viewed as capitalist villains. And it was not entirely unreasonable for the Cubans to also see the raiding of their players on home soil and overseas as connected to ongoing Miami and Washington efforts to bring down their entire revolution.

Duque’s final seasons in New York enjoyed a measure of success while never reaching the peak level of a first world championship outing. In 2000 he won in double figures for the third straight year, although he posted a losing record at 12-13; he also captured all three initial playoff decisions before dropping his lone World Series start in the intercity matchup with the crosstown Mets. There would also eventually be a career revival for the aging ace with the American League Chicago White Sox, where he spent a single championship season after a year on the disabled list (torn rotator cuff) while property of the Montreal Expos, plus a brief return stint with the Yankees in 2004 (where he posted a solid 8-2 ledger after a late-spring start due to ongoing recovery from the earlier injury). The second go-around in Gotham did feature still another postseason appearance; he started once without a decision in the Yankees’ ALCS loss to the Boston Red Sox.

A glorious career swan song unfolded with the Chicago stopover when the then-39-year-old veteran performed admirably (9-9, 5.12 ERA in 24 appearances, 22 starts) at the tail end of a strong White Sox starting rotation featuring Mark Buehrle, Freddy Garcia, Jon Garland, and fellow Cuban José Contreras. The highlight moment came with a crucial Game Three of the ALDS versus Boston when Duque entered in relief with the bases loaded and none out and vanquished the enemy uprising without surrendering a run. It was something of a last hurrah, nonetheless, as Hernández was promptly traded to the National League Arizona Diamondbacks after reaching his 40th birthday. A pair of moderately successful final big-league seasons were played out in somewhat vagabond fashion in Arizona and then back in New York with the National League Mets (where he was again traded in late May after only nine starts with Arizona). A final campaign with the Mets in 2007 concluded with foot surgery that would again wipe out an entire summer season the following year. A free agent at the end of 2008, the 43-year-old attempted brief and unsuccessful minor-league comebacks with the Texas Rangers (2009) and Washington Nationals (2010). Effectively finished with professional baseball after parting with the Washington organization in September 2010, Duque delayed announcing his official retirement until August of the following year.

In the end it would be Liván who would pile up notable career big-league numbers (178 wins, 355 decisions, 3,000-plus innings worked, and nearly 2,000 K’s) that would not only far outstrip the more celebrated El Duque but also quietly place the younger half-brother among the top Cuban big-league hurlers from any era. Only an illustrious quartet (Luque, Tiant, Pascual, and Cuéllar) can claim higher or even approximate totals for victories, career decisions, innings pitched, or strikeouts. If Livan’s 17-year career did not boast quite as many highlights or etch as many headlines as that of his older sibling, in the end it stands as a near-equal monument to the quality of modern-era Cuban baseball.

Duque’s big-league career would in the end never boast the numbers attached to his half-brother. Like Contreras, he arrived late on the big-league scene at age 32-plus and with most of his best years likely already behind him. His best big-league season was undeniable his first, and after the initial three years with the Yankees he only once more registered double digits in the victory column (11-11 during a penultimate 2006 campaign at age 41, split between the Diamondbacks and Mets). His best performances always seemed to come with the pressures of the postseason, where he owned an overall 9-3 ledger and where his 2.55 ERA was a marked improvement on his 4.13 career number. But his true legacy, like Liván’s, would inevitably rest mainly on his role as a pioneer among latter-day Cuban big-league imports.

El Duque returned to the media spotlight several years after retirement as a central figure in two important documentaries portraying the trials of Cuba’s national sport. The first, by award-winning Havana filmmaker Ian Padrón, earned only a controversial reception back in Havana but won a prestigious gold medal award at the 2008 Third Annual Cooperstown Baseball Film Festival sponsored by the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Padron’s Fuera de la Liga (Outside the League but with the alternate English title Dreaming in Blue) documented the 2003 National Series season of the Havana Industriales Blue Lions, a year that ended in postseason disappointment but featured the sensational rookie campaign of future big leaguer Kendrys Morales. The thrust of the film was the special national status of the Industriales club as the island’s clearcut fan favorite. A memorable earlier star with Industriales, Duque was highlighted throughout the reprise of team history and was also interviewed in New York as a featured “talking head” for Padron’s portrayal. It was the appearance and central role of the celebrated defector that in fact caused the film to be withdrawn by government censors from the prestigious Havana Film Festival.13 The second and far better known film was Mario Díaz’s classic ESPN 30 for 30 production entitled “Brothers in Exile” and recounting the dual related escapes from Cuba of the Hernández brothers. The ESPN documentary was based heavily on the 2001 Fainaru and Sánchez book The Duke of Havana, and thus also traced the defection stories of the pair no further than the highlight 1998 postseason events surrounding El Duque’s debut season with the Yankees.

Duque’s less familiar legacy remains intact in his homeland as a Cuban League record-holder and lasting icon of Cuba’s socialist baseball experiment. If he is rarely acknowledged in official circles, he remains cherished by proud fans. His most memorable mark in the record books — a .728 (126-47) career winning percentage — remains untouched two decades later despite two recent challenges.14 It is a record that may well prove unbreakable and while it may own its stature to a short 10-year career, it can also be argued that had Duque remained in his homeland he might well have finished on top of the heap in numerous other celebrated lifetime categories (such as total wins, strikeouts, and career shutouts among others). His strikeouts/walks ratio (1211/455) remains one of the best in league annals.

Most recently El Duque and the handful of other pioneering defectors from the waning years of the twentieth century (mostly pitchers) have been overshadowed by the dramatic exploits of those who have followed in the near tidal wave of exiled Cuban stars arriving on North American shores after 2010. While the handful of mostly veteran hurlers who opened eyes in the mid- and late 1990s were anything but invisible — Duque and Liván both occupied center stage with postseason MVP performances — they nonetheless always seemed something of an anomaly on the big-league scene. A decade into the new millennium Chapman, then Céspedes and Puig, and finally Abreu all seemed to signal a long-overdue renewed Cuban presence on the big-league scene; they appeared as harbingers of the future rather than rare and exceptional reminders of the past. But nonetheless, both El Duque and Liván today remain important centerpieces in the complex saga of evolving late twentieth and early twenty-first century USA-Cuba baseball relations.

This article originally appeared in “Cuban Baseball Legends: Baseball’s Alternative Universe” (SABR, 2016), edited by Peter C. Bjarkman and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Archibold, Randal C. “This Cuban Defector Changed Baseball. Nobody Remembers,” New York Times, March 18, 2016.

Bjarkman, Peter C. Cuba’s Baseball Defectors: The Inside Story (Lanham, Maryland and New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016), Chapter 5: “Brothers in Exile.”

Fainaru, Steve, and Ray Sánchez. The Duke of Havana: Baseball, Cuba, and the Search for the American Dream (New York: Villard Books, 2001).

Price, S. L. Pitching Around Fidel: A Journey Into the Heart of Cuban Sports (New York: Ecco Press, 2000).

Shouler, Kenneth. “El Duque’s Excellent Adventures — How Cuba’s Ace Pitcher Escaped Political Oppression to Become Part of a Great American Success Story,” Cigar Aficionado, March-April 1999: 78-99.

Wertheim, L. Jon, and Don Yaeger. “Fantastic Voyage — Three Fellow Refugees Say the Tale of Yankees Ace Orlando (El Duque) Hernández’s Escape from Cuba Doesn’t Hold Water,” Sports Illustrated 89:22, November 30, 1998: 60-63.

Documentary Films

Brothers in Exile (Mario Diaz, Producer), ESPN 30 for 30 documentary series, November 2014.

Fuera de la Liga (“Outside the League”) (Ian Padrón, Producer), independent film by an award-winning Havana filmmaker. (Shown at the 2008 Cooperstown Baseball Film Festival under the English-language title Dreaming in Blue.)

Notes

1 The full story of Cuban defectors and the serious implications of this phenomenon for both the Cuban League and the business of Major League Baseball is fully treated in Bjarkman, Cuba’s Baseball Defectors: The Inside Story, 2016.

2 Wertheim and Yaeger, Sports Illustrated 89:22, 60-63.

3 Arocha’s own defection story is outlined in Bjarkman, Cuba’s Baseball Defectors, 104-106, and examined even more thoroughly by New York Times reporter Randal Archibold (“This Cuban Defector Changed Baseball. Nobody Remembers,” March 18, 2006. Arocha would enjoy only moderate big-league success with the St. Louis Cardinals after signing a bargain-basement $15,000 bonus contract resulting from a special player draft designed by the big-league commissioner’s office.

4 Fernández would eventually sign with the San Francisco Giants at the age of 27 and win 19 big-league games over four seasons split between the Giants and Cincinnati Reds. His career was curtailed by injury, likely the result of overuse and pitching with an inferior seamless baseball while toiling in the Cuban League.

5 Arrojo, who was 32 by the time he debuted with Tampa Bay, also experienced a disappointing big-league career, held back by arm troubles that had already cropped up in his homeland. He would last five years in the big time, later moving on the Colorado and Boston, and like Fernández would post a career losing record.

6 Fainaru (The Duke of Havana, 91) quotes one Cuban sportswriter as complaining that “Liván is an imbecile. But he has more natural ability than his brother. El Duque would love to have Liván’s fastball.”

7 The Duke of Havana, 91. Fainaru relates this story about the television tube. When Liván was frustrated by unsuccessful efforts to obtain one for his broken set from local party officials, he related the incident to Joe Cubas on a team trip to Japan and the agent immediately bought the precious item. Supposedly the pitcher returned to Cuba telling his father Arnaldo (the source of Fainaru’s tale) that after receiving such help he had seen the light about life in Cuba and was ready to sign on with the agent.

8 Duque’s popular moniker and his choice of uniform number both in Cuba and later in the big leagues require some explanation. He was dubbed “The Duke” by Industriales fans because that had been the sobriquet by which his father had been known. And his uniform number 26 had nothing at all to do with Fidel Castro’s July 26 revolutionary movement but instead was chosen (both with Industriales and the Cuban national team and later with the Yankees and other big-league clubs) because his father had worn that numeral.

9 In what was rapidly becoming something of a comic opera, Paret was also suspended one year after the Atlanta Games for allegedly speaking by telephone with recent defector Rolando Arrojo, his former Villa Clara teammate. But like Mesa, Paret (who sat out the 1999 Pan Am Games and 2000 Sydney Olympics) was eventually reinstated and manned Team Cuba’s starting shortstop post between 2002 and 2009.

10 Hernández Nodar appears on the ESPN 30 for 30 documentary to candidly tell the story of his misadventures in his own words. He also earlier provided Wall Street Journal writer Christopher Rhoads (“Baseball Scout’s Ordeal,” April 24, 2010) with a lengthy interview detailing his misadventures in Cuba and expanding on his resulting prison experiences.

11 Also included in the party were Duque’s cousin Joel Pedroso, Romero’s wife, Geidy, and a last-minute add-on, Lenin Rivero whom none of the others previously knew. Two unnamed partners of Romero had also served as crew but returned once the planned rendezvous point at Anguilla Cay had been reached. Cuban ballplayer Jorge Toca had also planned to accompany the group but failed to appear on time for the departure. Toca defected a year later and eventually played with both the New York Mets and the Mexican League Tabasco Olmecas.

12 Details of those three days on Anguilla Cay are laid out by Fainaru and involve the refugees initially hiding from a first attempted air search by Miami-based Brothers to the Rescue planes. The stranded Cubans thought the aircraft belonged to the US Coast Guard and that if found they would be immediately sent back to Cuba. They did not know that Anguilla Cay belonged to the Bahamians and that the Bahamian government would therefore decide their fate. Readers wanting the full story of the escape adventure and the details of the American wet-foot, dry-foot policies governing such refugees should read Fainaru and Sánchez (Chapter 13).

13 Padrón, who himself defected from Cuba in 2015, is the son of celebrated Havana documentary film maker Juan Padrón, considered the father of Cuban film animation and the creator in 1970 of the famed Cuban cartoon character Elpidio Valdés. Fuera de la Liga was blacklisted at the 2007 Havana Film Festival but officials later relented only slightly and allowed it a one-time showing on Havana television (but only on the educational station with a local viewership and not on the nationwide primary Havana government channel).

14 Contrary to what some have reported, the Cuban League records of players departed from the island have never been expunged from official marks published in the annual Cuban Baseball Federation Guidebooks. The career marks of “defectors” were long shown with an asterisk (meaning “abandoned the country”) but lately that practice has been dropped. Only two other pitchers in league history have finished their careers with a .700-plus winning percentage: Norge Luis Vera (.721, 176-68, over a far more impressive 17 seasons) and defector Jose Ariel Contreras (.701, 117-50, over a shortened career that matched Duque’s at 10 seasons). More recently Sancti Spíritus ace Ismel Jiménez briefly flirted with the .700 standard in his own 10th season (he peaked with National Series #53 in 2014 at .696, 117-51), but his overall mark has begun to erode as his career has waned due to injury and a weakened supporting team roster.