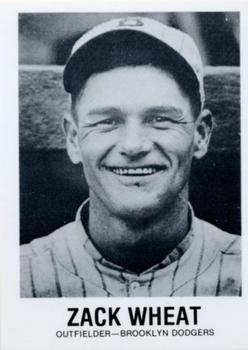

Zack Wheat: Native American?

This article was written by Rory Costello

For over a century, it’s been an article of faith in baseball history that Hall of Famer Zack Wheat’s mother was a Cherokee Indian. This statement started in his early days as a professional. It was repeated in numerous newspaper and magazine reports, and subsequently in various books, including the 2004 encyclopedia Native Americans in Sports. Wheat was also included (along with one of his autographed bats) in a 2008 exhibit at the Iroquois Indian Museum in Howes Cave, New York. Called “Baseball’s League of Nations: A Tribute to Native Americans in Baseball,” it drew large crowds and national press attention.1

For over a century, it’s been an article of faith in baseball history that Hall of Famer Zack Wheat’s mother was a Cherokee Indian. This statement started in his early days as a professional. It was repeated in numerous newspaper and magazine reports, and subsequently in various books, including the 2004 encyclopedia Native Americans in Sports. Wheat was also included (along with one of his autographed bats) in a 2008 exhibit at the Iroquois Indian Museum in Howes Cave, New York. Called “Baseball’s League of Nations: A Tribute to Native Americans in Baseball,” it drew large crowds and national press attention.1

The Internet has disseminated the Cherokee story even more widely. Yet it is likely a fabrication. The evidence shows that Julia Scott Wheat – mother of Zack and two other pro ballplayers, including big-leaguer Mack Wheat – was Caucasian.

SABR member Joe Niese, in his biography Zack Wheat: The Life of the Brooklyn Dodgers Hall of Famer (2020) treats Wheat’s presumed indigenous heritage in a nuanced discussion that examines the evidence on both sides and expresses reasonable doubt.2 It’s a welcome departure from the simple acceptance of the past. However, Niese does not state a specific view. Rather, he’s noted that the subject remains open to debate.3

Wheat himself was typically reticent on this topic. As Niese observes, he was “coy and at times playful regarding his lineage.”4 However, Wheat did deny it in his own words in September 1916. In the interview – which called him unusually talkative that day – Wheat pleaded, “And say, will you please say for me that I am not an Indian? They have been calling me a Cherokee so long that I almost believe it myself. My nationality is American of Scotch-Irish descent. They started calling me ‘The Indian’ for a nickname when I played with Shreveport and Mobile before I came to Brooklyn in 1909. It has got so that a lot of people really believe that I am an Indian.”5

Zack’s wife, Daisy Forsman Wheat, also apparently said that accounts of Wheat’s Native heritage weren’t accurate.6 Further attestation that Julia and her sons were non-Native comes from one of their descendants. Zack’s great-grandson, Zachary Alan Wheat, has long been involved in efforts to document the family’s genealogy. He has declared, “As far as the myth that he [Zack Wheat] was half Cherokee, that is all that it is and a story that has been told for many years. There is no truth to that whatsoever.”7

At least one other parallel exists among major-leaguers: Elon Hogsett, whose nickname – “Chief” – fueled the belief that he was part Indian. The press and fans just ran with it. Yet Hogsett actually had precious little Native American blood: one-thirty-second Cherokee, as he stated in a June 1982 interview. Still, the swarthy Kansan looked the part, and the well-worn moniker “just kind of stuck.”8 So it was with Zack Wheat, who also had a dark complexion, and whose athleticism was often attributed to Indians’ supposed innate abilities.

Looking back at early contemporary accounts, Niese mentions a report from 1908, Wheat’s second professional season, which referred to him by the nickname “Cherokee.”9 In June 1910, Wheat’s first full year in the majors, a Brooklyn Eagle article noted, “His mother was from the Cherokee tribe.”10 Another report, from later that month, was a mere snippet alleging that Wheat himself had said he was of Cherokee descent (rather than Potawatomi, as might have been supposed from his home, which was then in Kansas).11 Toward the end of the same month, a piece in the Boston Globe even referred to him as full Cherokee.12

Roughly two years later, a story about Wheat on the front page of Sporting Life mentioned – again without any support – that his mother was a full-blooded Cherokee.13 Subsequent stories simply took the assertion at face value and parroted it, replete with racist phrases and imagery.14 The most lurid was a January 1917 feature in Baseball Magazine.15

Niese observed that by the 1920s, “Wheat’s Native heritage…had disappeared as a reference point for sportswriters.”16 As late as 1943, though, Harry Grayson (who wrote a syndicated column for the Newspaper Enterprise Association) repeated the “half Cherokee” theme in a retrospective.17

According to Alan Wheat, the story of his forebear’s Cherokee heritage was more widely fostered by a Brooklyn publicity effort.18 When asked in 2019 if there was any clear evidence in support of this, he noted that he possessed an extensive archive of about 60 file boxes of newspaper articles and other things. He made an effort to work through those, but getting proof positive from such a volume of material proved fruitless.19

However, Alan did go through the scrapbook started by his great-grandmother, Daisy, and completed by his great-aunt, Mary Helen Wheat. The articles he did find regarding the family genealogy focused on the Wheat side, but he also found some articles in which Julia Scott Wheat was interviewed. In those, nothing was ever mentioned about her being Native American.20 The negative evidence is significant.

Whereas Elon Hogsett delighted in storytelling and offered at least two versions of how the belief arose that he was an Indian, Wheat wasn’t known as a raconteur. Aside from the 1916 denial, which didn’t get traction, he didn’t appear to stop the articles that called him Cherokee (at least not wholeheartedly). It would have been a blessing had he been part of Lawrence Ritter’s landmark book of oral history, The Glory of Their Times. It’s also unfortunate that SABR’s Oral History Committee has no interviews with Wheat in its archives. Yet even if such talks had taken place, whether the topic would have been addressed can only be conjectured. The Sporting News did run lengthy features with extensive quotes from Wheat and his wife in 1941 and 1959. Neither one had a single word about his ancestry.21

Yet one must also look at the official records, which weigh heavily against the Cherokee story.

Evidence is absent from the tribal angle. Julia Scott is not visible in the 1880 Cherokee census, and nobody named Wheat is listed in the 1907 Dawes Rolls, a U.S. government compilation of people accepted as members of “The Five Civilized Tribes.” However, this is subject to caveats.22

Convincing proof lies in the U.S. census records for 1870 and 1880. Julia Scott and her parents, John J.H. Scott and Matilda Jane (née Carson), are listed as “W” for White. Matilda’s uncle was the famous American frontiersman Kit Carson – who actually did have two Native American wives. However, genealogical research shows nothing to indicate any such heritage for John or Matilda.

Conclusive as that appears, further supporting evidence exists. The 1886 Missouri marriage certificate of Julia Scott and Basil C. Wheat does not contain anything beyond their names – but the Kansas state census of 1905 and U.S. census of 1910 do. The 1905 record shows Basil (who died in 1907), Julia, Zack, Mack, and Basil Jr. The 1910 record shows the widow living in Kansas City, Kansas with her sons, mother, and brother. In the column headed “Color or Race,” the notation for all again is “W” – not “I” or “In” for Indian, according to the codes used.23

Neither is there any indication of mixed parentage. Indeed, another government publication related to the 1910 census – expressly devoted to Indian population – specified that “all persons of mixed white and Indian blood who have any appreciable amount of Indian blood are counted as Indians, even though the proportion of white blood may exceed that of Indian blood.”24

It’s conceivable that the Wheats (and the Scotts before them) may have concealed the truth from census enumerators. Yet if that were the case, it raises the question of why – just a couple of months after the 1910 census was taken – Zack was supposed to have talked openly of this subject.

Furthermore, the 1920 and 1930 U.S. censuses also show Julia Wheat as White. Zack Wheat himself is listed again as White in the 1930 and 1940 U.S. census. The latter, as seen in previous years, had a system of classification with specific instructions for people of mixed race.25

Why should we care about Zack Wheat’s genealogy? Why should we care about ethnicity in general? First, Native American identity remains topical today. Moreover, it’s always prudent to re-examine the received wisdom on any issue.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Alan Wheat and Joe Niese for their input, as well as Paul Proia and Eric Costello for additional research.

This article was reviewed by Gregory Wolf and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Paul Proia.

Sources

Census records from Ancestry.com and Familysearch.org. The author also used Findagrave.com.

The Sporting Life Collection – LA84 Digital Library: https://digital.la84.org/digital/collection/p17103coll17

Notes

1 Vincent M. Mallozzi. “The American Indians of America’s Pastime,” New York Times, June 8, 2008. “Indian players featured in exhibit,” Miami Herald, August 17, 2008: 6D.

2 Joe Niese, Zack Wheat: The Life of the Brooklyn Dodgers Hall of Famer, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. (2020): 5-6.

3 Joe Niese, e-mail to Rory Costello, April 21, 2021.

4 Niese, Zack Wheat, 6.

5 “Wheat Wants to Go Back to Farm,” Ithaca (New York) Journal, September 25, 1916: 7.

6 Niese, Zack Wheat, 6. The underlying source for this statement is not presently available.

7 Alan Wheat, “Re: Oscar & Zack Wheat,” Genealogy.com, October 19, 2004 (https://www.genealogy.com/forum/surnames/topics/wheat/1614/). Reiterated in person in a telephone interview with Rory Costello, October 7, 2019.

8 Richard Bak, Cobb Would Have Caught It: The Golden Age of Baseball in Detroit (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1991).

9 Niese, Zack Wheat, 6. “Pirate News,” Shreveport Times, August 16, 1908: 7.

10 Brooklyn Eagle, June 3, 1910: 23.

11 “National League Notes,” Sporting Life, June 18, 1910: 9.

12 “Wagner Gets Back His Eye,” Boston Globe, June 27, 1910: 6.

13 “Zack D. Wheat,” Sporting Life, April 13, 1912: 1.

14 “Indian Is Slowly Passing From Game,” Chicago Eagle, August 21, 1915: 2. Various other newspapers across the country ran the feature on different days.

15 “Zach Wheat: Graceful Outfielder: What a Heritage of Indian Blood Has Done for Zach Wheat,” Baseball Magazine, January 1917: 48-51, 104.

16 Niese, Zack Wheat, 6.

17 Harry Grayson, “Black Lightning Zack Wheat Was Brooklyn’s Most Popular Player,” Courier-News (Blytheville Arkansas, June 29, 1943: 6. Again, various other newspapers across the country ran the feature on different days.

18 Alan Wheat, telephone interview with Rory Costello, October 7, 2019.

19 Alan Wheat, e-mail to Rory Costello, October 23. 2019.

20 Alan Wheat, e-mail to Rory Costello, October 23. 2019.

21 Harold W. Lanigan, “Zack Wheat, Now Running Sports Resort in Ozarks, Recalls His 18 Thrill-Filled Years of Fun as Dodger,” The Sporting News, November 30, 1941: 4. C.C. Johnson Spink, “Wheat Near Tears Over Shrine Election,” The Sporting News, February 11, 1959: 3, 6.

22 The presently available data for the 1880 Cherokee census are patchy. The Dawes Commission’s effort covered only people who lived with their tribe in Indian Territory and who chose to apply.

23 The 1905 Kansas record shows the key directly on the page. The 1910 codes are explained in “1910 Census Instructions to Enumerators,” U.S. Census Bureau (https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/technical-documentation/questionnaires/1910/1910-instructions.html).

24 “1910 Census: Indian Population in the United States and Alaska,” U.S. Census Bureau (https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1910/indian-population/indian-population-p2.pdf)

25 With regard to Indians, it said, “A person of mixed white and Indian blood should be returned as an Indian, if enrolled on an Indian agency or reservation roll, or if not so enrolled, if the proportion of Indian blood is one-fourth or more, or if the person is regarded as an Indian in the community where he lives.” (Author’s emphasis added.) See Sixteenth Decennial Census of the United States, U.S.. Census Bureau: 43. (https://www.census.gov/history/pdf/1940instructions.pdf).