April 12, 1918: Red Faber, White Sox win exhibition game in epicenter of influenza pandemic

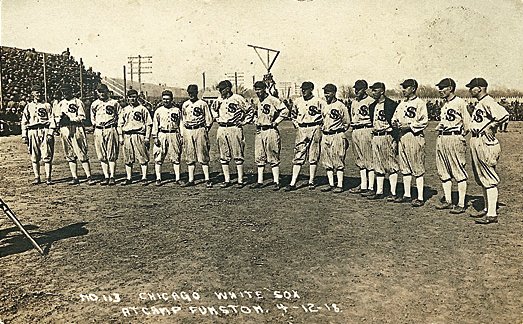

The Chicago White Sox are pictured on April 12, 1918, before an exhibition game against a US Army team at Camp Funston, outside of Junction City, Kansas. Just weeks earlier, the first major outbreak of a global influenza pandemic killed 38 soldiers at the base. An estimated 50 million people around the world died from the flu by the time the pandemic subsided in 1920. (Photo: BlackBetsy.com)

Less than a week before Opening Day of the 1918 season, as the Chicago White Sox made their way north from spring training, Eddie Collins woke up feeling weak and ill in Wichita, Kansas. The captain of the defending World Series champions decided to play that afternoon’s exhibition game against the Wichita Jobbers of the Western League. He went 0-for-5, an uncharacteristically poor performance, and Wichita’s minor-leaguers defeated the powerful White Sox.1

Afterward, Collins summoned a doctor and fainted in his hotel room while he was being examined.2 It was just a cold, maybe a bout of tonsillitis, the doctor said.3 Collins thought he had picked it up in Mineral Wells, Texas, the White Sox’ spring-training home for the past month. The sleeper train that had transported them to Kansas had been “without heat of any kind,” with few blankets on board to keep the players warm at night.4 Manager Pants Rowland sent his star second baseman home to Chicago to rest up for the start of the season.

The White Sox were scheduled to play another game on Friday, April 12, at Camp Funston, a hastily built military base outside of Junction City, Kansas, that housed more than 40,000 US Army soldiers training to go overseas to fight in World War I.5 The Army’s 89th Division baseball team, which included several future major leaguers, had beaten the St. Louis Cardinals twice in the previous seven days.6 White Sox owner Charles Comiskey had booked this game, and several others against military teams during spring training, as a show of baseball’s support for the troops, to help boost morale and provide entertainment before they went off to face the carnage of war.

What Comiskey did not know — what almost no one knew at the time — was that the White Sox were heading into the epicenter of the most devastating public-health crisis of the twentieth century. A new and virulent strain of the H1N1 influenza virus was first noticed in February in the farming community of Haskell, Kansas. Soldiers from that town who were home on leave unknowingly carried the virus back to Camp Funston, where by mid-March more than 1,100 soldiers had been admitted to the base hospital and 38 of them had died.7

The influenza virus spread rapidly after that, as US soldiers were transferred from base to base, and then quickly shipped overseas to join the war in Europe. By the time the global pandemic finally ended in early 1920, upward of 500 million people had been infected — nearly one-third of the world’s population — leaving an estimated 50 million dead, including around 675,000 Americans.8

But in the spring of 1918, no one at Camp Funston knew of the deadly horror that was to come. The first wave of the influenza pandemic attracted little attention at the time, in part because while thousands of people became infected quickly, relatively few died from the virus at first. Soldiers dismissed their mild symptoms of the flu as a “three-day fever” and no precautions were taken to stop the spread.9

Eddie Collins may have felt the same way about his own illness as he traveled back home to Chicago, accompanied by the White Sox’ Opening Day starter, Eddie Cicotte.10 After a few days of rest, Collins’s symptoms seemed to clear up, rather than develop into pneumonia as the doctors had feared. The flu that was quietly sweeping around central Kansas was likely the furthest thing from his mind.

In the meantime, pitcher Red Faber and the rest of the White Sox team were still at Camp Funston, ready to play an exhibition game with 7,000 soldiers in attendance. The troops received special permission to take the rest of the day off and watch baseball from the base’s top commander, Maj. Gen. Leonard Wood, who had just returned from France and was the guest of honor with his wife, Louise.11 The 50-cent admission fee for everyone in attendance went toward the camp’s athletic equipment fund.

In the meantime, pitcher Red Faber and the rest of the White Sox team were still at Camp Funston, ready to play an exhibition game with 7,000 soldiers in attendance. The troops received special permission to take the rest of the day off and watch baseball from the base’s top commander, Maj. Gen. Leonard Wood, who had just returned from France and was the guest of honor with his wife, Louise.11 The 50-cent admission fee for everyone in attendance went toward the camp’s athletic equipment fund.

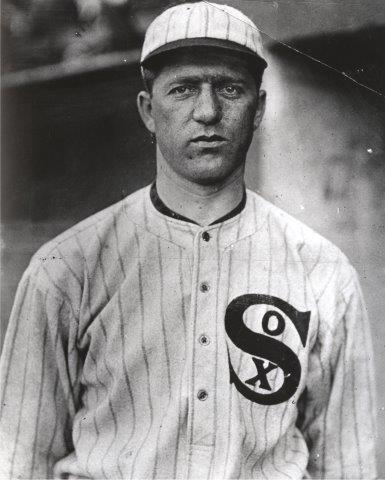

Faber had been the White Sox’s biggest star in the 1917 World Series, recording three wins over the New York Giants. The right-hander from Cascade, Iowa, expected to face little opposition against the 89th Division team, which included future St. Louis Browns outfielder Dutch Wetzel, future NFL football coach George “Potsy” Clark, and Philadelphia A’s pitcher Win Noyes.

Faber allowed just two hits against the Army team in five innings, while Noyes and a pair of relievers were knocked around by the White Sox’ powerful lineup. Happy Felsch delivered the big blow with a grand slam to left field in the fourth. Nemo Leibold also homered, while Chick Gandil, Swede Risberg, and Fred McMullin all had extra-base hits.12 The military newspaper Trench and Camp reported, “At no time did the division team look dangerous to the Comiskey players for they all seemed to be in the finest shape.”13

After the game the White Sox said goodbye to the soldiers and left for Kansas City to play their final exhibition series against the Kansas City Blues of the American Association. Despite their proximity to anyone at Camp Funston who may have been carrying the influenza virus, none of the White Sox players except Eddie Collins publicly reported any flu-like symptoms before their Opening Day game against the St. Louis Browns on April 16.

One day after the White Sox left Kansas, their crosstown rivals, the Chicago Cubs, learned that star pitcher Grover Cleveland Alexander’s draft number had been called and he would miss most of the baseball season. He was ordered to report to military duty by the end of April — at Camp Funston.14

The dark cloud of war dominated headlines all summer long. In July the US government issued a “work or fight” order to all able-bodied men that shortened the baseball season and forced the World Series to be played in early September. By then, the second wave of the influenza pandemic was in full force and millions of people would die throughout the fall.

White Sox pitcher Red Faber, who had easily beaten the Camp Funston team in his final tune-up, was one of the baseball players who reportedly contracted the flu after the season ended. He recovered in time to report to spring training in 1919, but he had lost nearly 20 pounds by the time he arrived. His weakened state, combined with recurring ankle injuries, caused his performance to fall far below his usual Hall of Fame-caliber standard.

Although the White Sox won the American League pennant in 1919 for the second time in three years, Faber was left off the World Series roster and failed to make an appearance against the Cincinnati Reds. His absence in that fateful fall classic — which eight of his teammates conspired to lose in exchange for bribes from gamblers — was far more noticeable than Eddie Collins’s absence from a preseason exhibition game, played in the heart of a health crisis that rocked the entire world.

An earlier version of this story was published in the SABR Black Sox Scandal’s June 2021 committee newsletter.

Sources

No box score or full play-by-play for this game has been uncovered, but the most extensive coverage of the game and players involved was found in:

Fisher, H.E. “Sox Wallop Army,” Trench and Camp (Fort Riley, Kansas), April 20, 1918: 1.

Robbins, George S. “Gen. Wood Sees Sox Play His Camp Team,” Chicago Daily News, April 12, 1918: 2.

Sanborn, I.E. “10,000 Funston Boys Watch Sox Bombard Camp’s Team, 13 to 1,” Chicago Tribune, April 13, 1918: 9. (Note: The score in this headline does not match any other coverage of the game. Every other account has the White Sox winning 12-1.)

Baseball Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Notes

1 “Wichita Pitcher Beats Champs,” Wichita Beacon, April 12, 1918: 7. The Jobbers’ team president was Frank Isbell, a White Sox hero in the 1906 World Series.

2 I.E. Sanborn, “Eddie Collins Forced to Quit Sox by Illness,” Chicago Tribune, April 12, 1918: 9.

3 George S. Robbins, “Gen. Wood Sees Sox Play His Camp Team,” Chicago Daily News, April 12, 1918: 2; “Collins Too Ill to Play,” Kansas City Star, April 12, 1918: 21.

4 Sanborn, “Eddie Collins.”

5 “Camp Funston,” Kansapedia, Kansas Historical Society, accessed online at https://www.kshs.org/kansapedia/camp-funston/16692 on May 31, 2021.

6 “Ball Season On,” Topeka State Journal, April 6, 1918: 1.

7 John M. Barry, “How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America,” Smithsonian Magazine, November 2017, accessed online at https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/journal-plague-year-180965222/ on May 31, 2021.

8 “1918 Pandemic (H1N1 Virus),” Centers for Disease Control and Protection, https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html, accessed May 7, 2020.

9 Barry, “How the Horrific 1918 Flu.”

10 I.E. Sanborn, “10,000 Funston Boys Watch Sox Bombard Camp’s Team, 13 to 1,” Chicago Tribune, April 13, 1918: 9.

11 H.E. Fisher, “Sox Wallop Army,” Trench and Camp (Fort Riley, Kansas), April 20, 1918: 1.

12 Fisher, “Sox Wallop Army.”

13 Fisher, “Sox Wallop Army.

14 James Crusinberry, “Cubs’ Hopes Wrecked with Aleck Drafted,” Chicago Tribune, April 14, 1918: 17.

Additional Stats

Chicago White Sox 12

US Army 89th Division 1

Camp Funston

Junction City, KS

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.