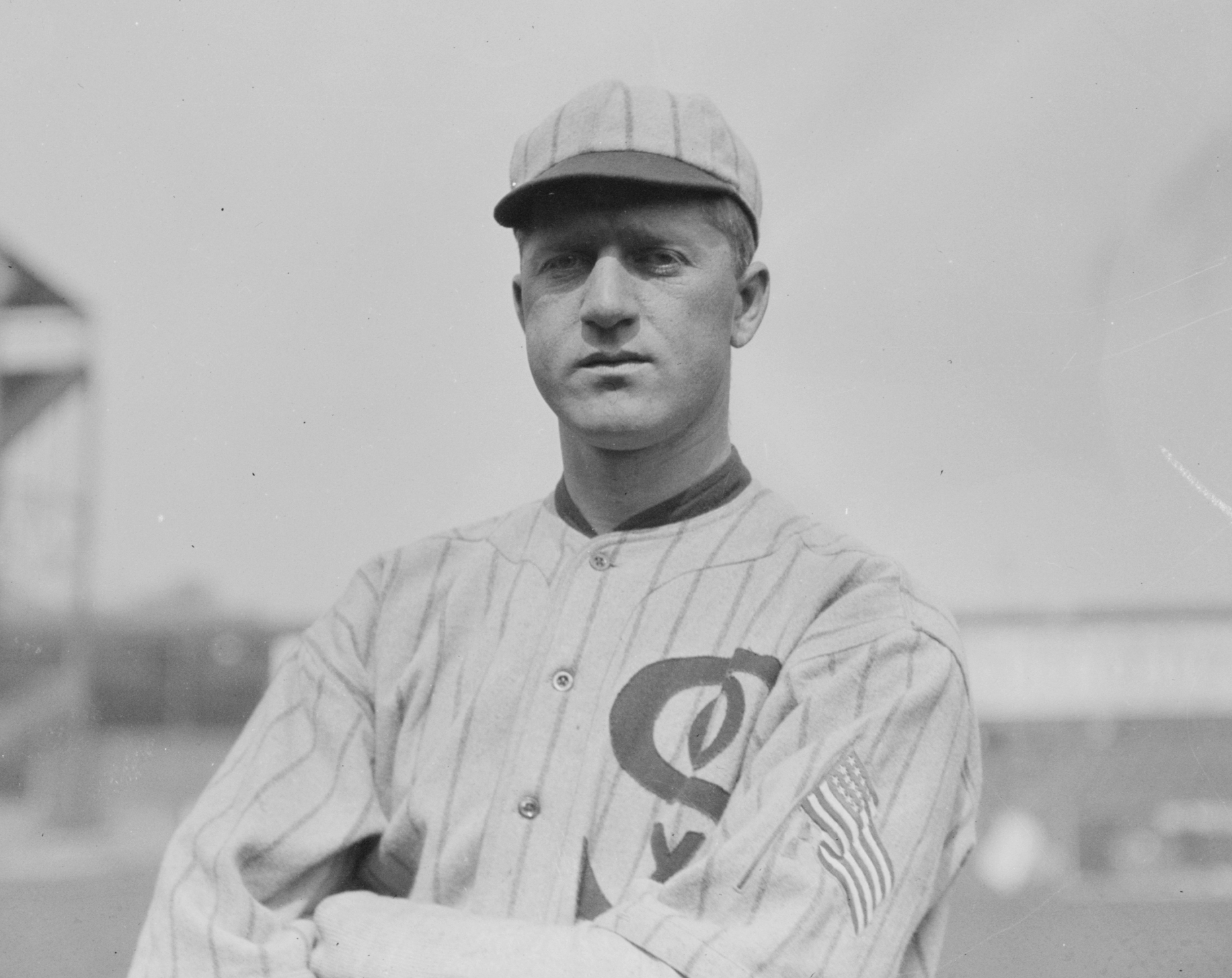

Red Faber

Urban “Red” Faber, one of the last pitchers to legally throw a spitball, persevered through illness and injury, a world war, and the Black Sox Scandal to win a place in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Urban “Red” Faber, one of the last pitchers to legally throw a spitball, persevered through illness and injury, a world war, and the Black Sox Scandal to win a place in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

The right-hander played his entire 20-year major-league career with the White Sox, one of the league’s strongest teams before the scandal and a perennial also-ran afterward. Faber won 254 games — a total that Ray Schalk, Faber’s longtime batterymate and friend, contended might have reached 300 had the team not been decimated after its misdeeds came to light in 1920.1

He learned the spitball, the pitch that brought him major-league success, in the minor leagues, after an arm injury jeopardized his career. “I never resorted to the spitter until I was obliged to,” Faber later said. “I nearly ruined my arm throwing curves.”2 Wetting the tips of the first two fingers on his right hand, Faber threw the spitter from a variety of arm angles, befuddling batters with the pitch’s late-breaking downward movement. “A batter cannot guess with Faber,” Goose Goslin remarked. “His only chance is to close the eyes and hope bat meets ball.”3 To get the consistency required to throw his spitter, Faber was known to chew a combination of slippery elm and tobacco, though he preferred the latter. “And I don’t chew [tobacco] because I like it, either,” explained Faber, a lifelong smoker. “In fact, I never chew except when I am pitching.”4

Urban Clarence Faber (some references incorrectly list his middle name as Charles) was born on his parents’ farm near Cascade, a tiny community in northeast Iowa, on September 6, 1888. The second of four children born to Nicholas and Margaret Grief Faber, he was of Luxembourg descent. German was the primary language spoken in the Faber home and at the Catholic elementary school the Faber children attended. In 1893 the family moved into Cascade, where Nicholas operated a tavern and then opened the Hotel Faber. With his real-estate holdings and successful hotel, Nicholas Faber became one of Cascade’s most affluent citizens. The Fabers could afford to send the children to out-of-town prep schools and colleges, and for several years before World War I they lived off of Nicholas’s investment income.5

The red-haired Faber apparently had a sporadic and unspectacular high-school baseball career. He attended prep academies associated with colleges in two Mississippi River communities — Sacred Heart, in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, and then St. Joseph’s in Dubuque, Iowa. In 1909, when he was 20 and studying at a Dubuque business school, he joined the college varsity of his prep alma mater, St. Joseph’s. The institution, now Loras College, has no record of Faber taking any college classes there; however, there is ample documentation of his dominance over college batters in 1909, when St. Joseph’s went undefeated in its half-dozen games.6 The highlight was Faber’s 22-strikeout performance against St. Ambrose College, which mustered only three hits.

Faber’s performance for St. Joseph’s and semipro clubs caught the attention of Clarence “Pants” Rowland, former owner of Dubuque’s minor-league team and an acquaintance of Chicago White Sox owner Charles Comiskey. (Rowland was between baseball jobs at the time, managing a hotel bar in Dubuque.) Rowland encouraged Faber to sign with the Dubuque Miners, who were struggling in the Class B Three-I (Illinois-Indiana-Iowa) League. Joining the team with two months left in the 1909 season, Faber went 7-6. In August 1910, during his first full season as a professional, Faber (18-19) threw a perfect game against Davenport; only one ball reached the outfield. The Pittsburgh Pirates bought his contract the next day.

Faber made the Pirates’ 1911 Opening Day roster, but manager Fred Clarke never used him and in mid-May sent him to Minneapolis of the American Association. Within days of his arrival in Minnesota, Faber entered a distance-throwing contest and injured his pitching arm. During his short stay in Minneapolis, Faber had a career-changing experience: Teammate Harry Peaster taught him the finer points of the spitball, which at the time was a legal pitch.7

Within weeks the sore-armed Faber was shipped to Pueblo of the Western League. The young Iowan worked on his spitter over the next 2½ seasons, first in Pueblo and then for two years with Des Moines of the Western League. In 1913, his second year in Des Moines, Faber solidified an “iron man” reputation, sometimes pitching on consecutive days and once, during an Iowa heat wave, pitching all 18 innings of a tie game ended by darkness. In the closing weeks of the 1913 season, White Sox owner Comiskey bought Faber’s contract for 1914.

Faber’s offseason was abbreviated. In October 1913, at the urging of Rowland, Comiskey belatedly added Faber to the White Sox roster for the around-the-world exhibition tour with the New York Giants. The rookie-to-be performed adequately on the domestic leg of the tour, but Comiskey planned to drop Faber from the squad before departure for Japan, Australia, the Mideast and Western Europe.8 However, Faber caught another break: Just hours before the teams embarked on their Pacific crossing, Giants pitcher Christy Mathewson, the most popular American athlete of the day, quit the tour because he feared becoming seasick on the journey. Comiskey and Giants manager John McGraw made an agreement: Faber was loaned to the Giants to take Mathewson’s place.9

Mathewson must have felt vindicated in his decision to remain stateside: A powerful storm nearly wrecked the teams’ ship as it crossed the Pacific, and all the passengers experienced bouts of seasickness. None suffered more than Matty’s replacement, Faber, who was too ill to leave the ship for a day or two after its arrival in Japan. Eventually, Faber took regular turns pitching against his future team. In the finale, in London, with King George V in attendance, Faber pitched tenaciously for 11 innings but took the loss. On the voyage back to the United States, McGraw tried to buy Faber’s contract. Comiskey refused.10

After a no-decision start and a handful of relief assignments, the 6-foot-2, 180-pound rookie forged into the national spotlight in June 1914. On June 1 Faber pitched 12⅓ innings in a 2-1 loss to Detroit. Six days later, he earned his first major-league victory with a three-hit shutout of the New York Yankees. Ten days after that, Faber came within three outs of no-hitting defending World Series champion Philadelphia; an infielder’s slow work on a bouncer allowed the only hit. He cooled off in the second half of the season — a sore elbow sidelined him for a month — and finished 10-9 with a 2.68 ERA.

Before the 1915 season, Comiskey surprised the baseball world by selecting Pants Rowland, who lacked any major-league playing or managing experience, as the White Sox manager. Faber responded to the new skipper, posting a 24-14 record with a 2.55 ERA. Though the spitball was a big part of his repertoire, Faber also relied on his fastball and curve. He said that just the awareness that he might unleash a spitter at any time was enough to keep most batters guessing.11 His forte was getting hitters to swing early in the count and beat the ball into the ground. That skill was best demonstrated on May 12, 1915, in Comiskey Park, when Faber required a record-low 67 pitches to defeat Washington.12 Faber pitched less in 1916 due to injury, but he improved to 17-9 with a 2.02 ERA for a team that lost the pennant by two games.

Faber’s competitive fire and pleasant personality made him popular with White Sox fans and management — though later in his career, as his losses due to teammates’ miscues mounted, he became crankier and a manager briefly benched him.

Comiskey, who owned a Wisconsin game preserve, named a moose after his young pitcher. In September 1916 the moose escaped; it startled a couple of local youths, one of whom happened to be carrying a rifle. When word of the incident reached the Chicago newspapers, headline writers had some fun. One headed an article, “Shoots Red Faber, Pride of Comiskey! Moose, not pitcher.”13

Faber was a battler. In a single at-bat, he decked Ty Cobb on three consecutive knockdown pitches. He also earned opponents’ respect. Babe Ruth, who once described Faber as “the nicest man in the world,”14 shook hands and posed for pictures with the spit-baller at Red Faber Day at Comiskey Park in 1929.

In 1917 Faber posted a career-best 1.92 ERA, winning 16 games for the White Sox en route to their first pennant in 11 seasons. In the World Series, against New York, Faber tied a Series record with three victories. He won Game Two, lost Game Four, won Game Five in relief, and then closed out the host Giants with a complete-game victory in Game Six. His pitching performance overshadowed his baserunning blunder in Game Two, when he tried to steal third while it was occupied by teammate Buck Weaver.

With World War I raging as the 1918 season opened, it appeared likely that major leaguers would be drafted into military service. As a 29-year-old bachelor, Faber was virtually certain to be conscripted. He won his first four decisions, enlisted in the Navy, and lost his farewell game. Though he told reporters that he wanted assignment to a submarine15 — apparently he forgot his seasickness during the world tour — Faber served his entire tour at Great Lakes Naval Base, near Chicago. A chief yeoman, he supervised recreation programs and pitched for the base team for the duration of the war.

Back in a baseball uniform for 1919, Faber (11-9) struggled with the flu — he was weak and underweight — and with arm and ankle injuries. After a layoff of several weeks, he struggled in his only appearance during the final month of the regular season and remained on the bench throughout the tainted 1919 World Series. White Sox catcher and fellow Hall of Famer Ray Schalk long contended that the Black Sox Scandal would have been impossible had Faber been healthy; the conspirators would not have had enough pitching to succeed.16

After the 1920 season, the 32-year-old Iowan married 22-year-old Milwaukee native Irene Margaret Walsh, of Chicago. They met by accident — literally. He was a bystander who came to her assistance after she was hurt in an auto collision. The couple had no children, and she experienced ongoing health problems that reportedly included dependency on painkillers. A Faber relative described their marriage as unhappy.17 There were whispers that she became romantically involved with White Sox outfielder Johnny Mostil, and that his 1927 suicide attempt occurred after Faber confronted him about the affair. (More likely Mostil became despondent when he learned that his longtime girlfriend had thrown him over for his teammate Bill Barrett, whom she subsequently married.) In any case, the Fabers remained married until March 1943, when Irene died of a cerebral hemorrhage at age 44.

The advent of the lively-ball era coincided with the best three-season stretch of Faber’s career (1920-22), when he went a combined 69-45 and led the league in ERA in 1921 and 1922. He was among the 17 “grandfathered” pitchers permitted to throw the otherwise banned spitball for the rest of his career. In 1921, when the White Sox were a shambles after the Black Sox indictments, Faber’s 25 wins (against 15 losses) represented 40 percent of all the team’s victories. He followed that with his third consecutive 20-win season (21-17). But after 1923, when he went 14-11, it was clear that Faber’s days of dominance were behind him; age, injury, and White Sox ineptitude took their toll. He suffered his first losing season (9-11) in 1924, when he got a late start after elbow surgery.

As early as the mid-1920s, sportswriters started predicting Faber’s retirement. But he remained generally effective, and kept returning, season after season. He explained his longevity by noting that the spitball exerted less stress on his arm.18 Faber showed occasional flashes of his old form. He registered his third and final career one-hitter in 1929.

In 1932 new manager Lew Fonseca took Faber out of the starting rotation, and his record tumbled to 2-11. By 1933, his 20th season in the majors, Faber (3-4) was the American League’s oldest player — he turned 45 that fall — and its last “legal” spit-baller. (A grandfathered National League spitballer, Burleigh Grimes, crossed over and pitched 18 innings for the 1934 Yankees.) In the postseason City Series against the Cubs, Faber got the Game Two start at the last minute. He responded with his best performance in years, a five-hit shutout. Though no one knew it at the time, it was Faber’s last appearance against major-league competition.

After a combined 5-15 record the previous two seasons, Faber was upset with his 1934 contract offer from the White Sox, who wanted to cut his pay by one-third, to $5,000. He secured his release and hoped to join another major-league team, but there were no takers. He closed his career with a 254-213 record.

In retirement Faber tried his hand at selling cars and real estate — his low level of success was attributed to his high level of honesty — before acquiring a bowling alley in suburban Chicago. Early in the 1946 season, Ted Lyons became the White Sox manager and hired Faber as pitching coach; they lasted three seasons.

In April 1947 the 58-year-old Faber married 29-year-old divorcee Frances Knudtzon. They became parents the next year with the arrival of their only child, Urban C. Faber, II, nicknamed Pepper. In the mid-1950s, the Cook County (Chicago) Highway Department hired Faber; he worked on a survey crew until he was nearly 80.19

In the late 1950s Pepper Faber’s Little League team, the Rebels, might have been the only Little League squad in the nation to have two ex-major leaguers as assistant coaches — Pepper’s father and Nick Etten, who had played first base for the Yankees, Phillies, and Athletics. Urban tossed batting practice and helped manager Ted Cushing wherever needed and without interfering. “If a first-base umpire is needed, Red takes the job,” columnist and neighbor Bill Gleason wrote, “and the opposing manager knows all decisions will be fair.”20 In 1963, when he was 14, Pepper Faber suffered a broken neck and nearly died in a swimming accident. Though he survived, health problems continue to dog Urban II.

Exactly 50 years after his rookie season, in 1964, Red Faber was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. His acceptance speech lasted 100 words:

“Mr. Commissioner, ladies and gentlemen. It’s a great honor to me to be named to the Hall of Fame. It’s very hard for me to even imagine that I would ever be elected to it. But now that I am, and about to join all those celebrities that I used to know and play against and with, why, I hardly know what to say. I know there are all baseball fans here. They must be or they wouldn’t have come this far to see an event like this. And I’m happy to greet you all in our behalf. Thank you.”21

In retirement, Faber was among the founders of Baseball Anonymous, an organization created to help former ballplayers (and athletes from other sports) who were down on their luck. Growing to nearly 700 members (at $2 per year) in its first year, Baseball Anonymous performed many good deeds; most were handled quietly, but in 1958, when Faber was the group’s general chairman, Baseball Anonymous arranged a Comiskey Park ceremony to honor former White Sox pitching great Ed Walsh, who was 77 years old and struggling physically and financially.22 The group also staged benefits for other former players who had fallen upon hard times. Faber was a regular at Hot Stove League banquets and old-timer’s games in Chicago and Milwaukee.

Faber, who took up the habit of smoking at age 8, suffered two heart attacks within a two-year period in the mid-1960s. He experienced increasing heart and respiratory problems in later years. He died at home on September 25, 1976, at the age of 88. He was survived by his wife, Frances, who died in 1992, and their son. Red Faber’s grave marker in Chicago’s Acacia Park Cemetery cites his Navy service but makes no mention of his baseball glory.

An expanded version of this biography was published by Brian Cooper as “Red Faber: A Biography of the Hall of Fame Spitball Pitcher” (McFarland & Co., 2006). This version appeared in “Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox” (SABR, 2015), edited by Jacob Pomrenke.

Sources

Associated Press

Baseball Magazine

Cascade (Iowa) Pioneer

Chicago American

Chicago Tribune

Elfers, James E., The Tour to End All Tours (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2003)

Farrell, James T., My Baseball Diary (New York: A.S. Barnes and Company and The Copp Clark Company, Ltd., 1957. Board of Trustees, Southern Illinois University, 1998)

Iowa Historical Society

Lindberg, Richard C., The White Sox Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1997)

Loras College, Dubuque, Iowa

New York Times

Retrosheet.org

St. Louis Star

Society for American Baseball Research; various publications

Sporting Life

The Sporting News

Dubuque (Iowa) Telegraph Herald

United States National Archives

Washington Post

Notes

1 The Sporting News, October 16, 1976.

2 Baseball Magazine, September 1922.

3 St. Louis Star, May 15, 1931.

4 Baseball Magazine, September 1922.

5 1910 Census, US Department of Commerce and Labor, and Dubuque city directories. Nicholas Faber’s occupation is listed on census records as “own income.”

6 “Retrorsum,” Columbia (now Loras) College, 1923.

7 The Sporting News, October 16, 1976.

8 James E. Elfers, The Tour to End All Tours, 82.

9 Elfers, 28; Lee Allen, “Cooperstown Corner,” May 30, 1964.

10 Elfers, 28.

11 The Sporting News, October 16, 1976.

12 Sporting Life, May 22, 1915.

13 Chicago Tribune, September 27, 1916.

14 Palimpsest, Iowa Historical Society, Vol. 36, No. 4, 1955.

15 Cascade (Iowa) Pioneer, June 13, 1918.

16 Associated Press, February 5, 1964.

17 Mary Ione Theisen, a niece, interview with author, June 18, 2003.

18 Christian Science Monitor, August 3, 1964.

19 The Sporting News, October 16, 1976.

20 Chicago American, June 13, 1958

21 Associated Press, July 29, 1964.

22 The Sporting News, July 2, 1958.

Full Name

Urban Clarence Faber

Born

September 6, 1888 at Cascade, IA (USA)

Died

September 25, 1976 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.