April 13, 1953: Max Surkont spins shutout in Milwaukee Braves’ first game

A month before Opening Day 1953, the Cincinnati Reds were expecting to kick off their season by hosting the Pittsburgh Pirates. On March 18, though, the National League club owners convened in St. Petersburg, Florida, to consider the transfer of Lou Perini’s Boston Braves to Milwaukee. Dodgers president Walter O’Malley made the motion, Horace Stoneham of the Giants seconded, and the ayes carried the vote unanimously. Milwaukee had a new ballclub, and the Reds had a new opponent for the opener. They also had a new name: Redlegs. To avoid being suspected of Communist leanings, club officials changed the team’s longtime nickname.

A month before Opening Day 1953, the Cincinnati Reds were expecting to kick off their season by hosting the Pittsburgh Pirates. On March 18, though, the National League club owners convened in St. Petersburg, Florida, to consider the transfer of Lou Perini’s Boston Braves to Milwaukee. Dodgers president Walter O’Malley made the motion, Horace Stoneham of the Giants seconded, and the ayes carried the vote unanimously. Milwaukee had a new ballclub, and the Reds had a new opponent for the opener. They also had a new name: Redlegs. To avoid being suspected of Communist leanings, club officials changed the team’s longtime nickname.

Perini’s Boston club had been hemorrhaging money. The team lost $600,000 in 1952, the biggest one-year deficit by any ballclub ever. No major-league franchise had changed cities in half a century, but Perini felt it was time. Despite personal pleas from the governor of Massachusetts and the mayor of Boston, Perini took his forlorn franchise to Wisconsin.

As the Braves flew to the Queen City the night before their historic debut, certainly none of them knew that Milwaukee’s major-league clubs had a decidedly unfavorable record in season openers. The 1878 Milwaukee Grays lost their National League lid-lifter to the Cincinnati Reds, 6-4, owing largely to the 10 errors they committed. In their first game of the inaugural 1901 American League, the Milwaukee Brewers carried a 13-4 lead into the bottom of the ninth inning in Detroit and then imploded, giving up 10 runs and losing, 14-13. Talk about needing a closer!

Because Crosley Field offered a small seating capacity and Opening Day typically attracted a sellout crowd (generally the only one of the year), some of the 30,108 fans were permitted to occupy a temporary seating/standing area on the playing field in front of the outfield fence. By ground rule, any batted ball entering that area was declared a double. Five such crowd-assisted two-base hits occurred in the 1953 opener. The number would have been larger if not for the defensive magic of the Braves’ rookie center fielder.

Billy Bruton was that rookie, but he was no stranger to Milwaukee. In 1952 he had played center field for the Milwaukee Brewers of the American Association, the Triple-A farm team of the Boston Braves. Bruton batted .325 while leading the league in at-bats, hits, and runs scored. Bruton was new to Crosley Field. In fact, he was the only player in either club’s lineup who had not played in Crosley Field before. He came late to baseball. He was 24 years old when he was discovered in 1949 playing softball in Wilmington, Delaware.1 The person who spotted him and recommended him to the Boston Braves was Negro League legend Judy Johnson, who is now in the Hall of Fame. Johnson later became Bruton’s father-in-law.

The Reds (oops, sorry, Redlegs) and Braves were the only teams in action on April 13. The Senators had been scheduled to host the Yankees to open the American League season, but they were rained out in Washington. That meant everything that happened in Crosley Field was a first – in the 1953 season or in the Milwaukee Braves’ short history. The opposing managers, Rogers Hornsby and Charlie Grimm, were in their first full seasons with their respective clubs, but they had been teammates with the Chicago Cubs over 20 years earlier. In fact, in 1931 each batted .331, with Grimm actually leading the great Hornsby by nine ten-thousandths of a point.

Bruton began the long list of firsts as the first batter in the game. He stroked a Bud Podbielan pitch into left field for a single. Two batters later, Bruton stole second, heralding the fact that he would lead the NL in steals in each of his first three seasons. When Sid Gordon bounced a ball up the middle, Bruton scored the first run of a) the game, b) the 1953 major-league season, and c) his career. On this day, one run was all the Braves would need, thanks to Max Surkont.

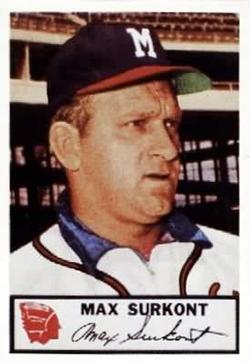

Burly right-hander Surkont was the embodiment of the term “journeyman.” Signed by the St. Louis Cardinals at age 15 after lying about his age at a tryout,2 Surkont pitched for eight seasons in the bush leagues before finally getting his chance with the Chicago White Sox in 1949. He was a three-year starting pitcher for the Boston Braves who had won 12 games in each of the two previous seasons but who lost more games than he won in both years. His choice by manager Grimm to start the Milwaukee Braves’ historic initial game was probably surprising to some people, but the Boston Braves in 1952 had been a bad seventh-place outfit. They had no returning starting hurler with a winning record, not even Warren Spahn. The great southpaw had achieved an ERA of 2.98, but his won-lost record was 14-19. Spahn was naturally reserved for the next day’s home opener anyway, so the maiden voyage fell to Surkont. As it turned out, Surkont made a genius out of Grimm. Big Max not only tossed a three-hit shutout at Cincinnati in the opener but went on to victory in nine of his first 10 decisions of the season.

In the top of the third inning, Bruton slammed a ground-rule double into the temporary seats in center field. It would have been a putout in any other big-league park or on any other day, but instead it became the first extra-base hit in Milwaukee Braves history.

Braves catcher Del Crandall led off the fifth inning with a double down the left-field line. Second baseman Jack Dittmer drove him home with a sharp single to right, which wrapped up the scoring for the day. Dittmer tried to stretch his hit into a double but was tagged out at second. After Surkont singled to center, the first base hit by a Milwaukee Braves pitcher, Bruton grounded into a double play, another Braves first.

The list of Redlegs highlights for the day was modest. Perhaps starter Bud Podbielan deserves kudos for holding the Braves batters to two runs in eight innings while walking just one. This was notable for a man who, exactly five weeks later, would issue the Brooklyn Dodgers 13 bases on balls in a 10-inning contest and still somehow defeat them. Gus Bell and Hobie Landrith belted fly balls into the temporary seats in the second and fifth innings, respectively, and Bobby Adams singled in the third, but that was it. No Redlegs baserunner scored. None advanced as far as third base. Surkont’s spitball (his best pitch) and his pinpoint control (complete game, no walks) were working and deserved much of the credit.3 Surkont, though, was wise enough to realize that a major factor in his success that afternoon was the sparkling defense of Billy Bruton.

Bruton’s fielding heroics began in the third inning. Willard Marshall pounded a drive toward the temporary seats in left-center. Bruton got a good jump, made a leaping stab with his outstretched glove, and snared the ball before it could disappear into the crowd. In the eighth inning, he did a repeat performance on a long fly off the bat of Landrith, with the same result. Then, almost before he had time to catch his breath, Bruton sprinted into short center toward a blooper off the bat of pinch-hitter Grady Hatton. As he lunged for the ball, Bruton collided with shortstop Johnny Logan and collapsed in a heap, the ball still lodged in his glove. Bruton remained on the ground for several anxious minutes, then slowly got to his feet and jogged back to his position.

“Johnny’s elbow knocked the wind out of me,” Bruton explained to reporters after the game.4

Bruton saved his best for last. Leading off the bottom of the ninth, Bobby Adams ripped a line drive deep into center field. Bruton turned and galloped to the edge of the crowd on the field and robbed Adams of extra bases. An accommodating Cincinnati fan allowed Bruton to brace himself against him so he could make the catch. “If he hadn’t helped me,” the star rookie said later, “I would have fallen over the railing and Adams would have had a ground-rule double.”5 Instead, with a huge lift from Bruton’s glove work, Surkont was able to retire the last 14 batters he faced.

As he headed toward his postgame shower, winning pitcher Surkont gave an apt illustration of the difference between the 1952 Boston Braves and the 1953 Milwaukee Braves. “I wouldn’t have won this game a year ago,” he said, “because we didn’t have a center fielder like Bruton to catch long flies. I would have lost by a score of six or seven to two. He meant the difference between winning and losing.”6

This article was published in “Cincinnati’s Crosley Field: A Gem in the Queen City” (SABR, 2018), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To read more articles from this book at the SABR Games Project, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the Notes, the author also accessed Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, the BioProject of the Society for American Baseball Research, and The Sporting News, April 22, 1953.

Notes

1 John Harry Stahl, “Bill Bruton,” in Gregory H. Wolf, ed., Thar’s Joy in Braveland: The 1957 Milwaukee Braves (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2014), 27.

2 David E. Skelton, “Max Surkont,” BioProject, Society for American Baseball Research, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/0bace006.

3 Ibid.

4 Sam Levy, “Surkont,” Milwaukee Journal, April 14, 1953.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

Additional Stats

Milwaukee Braves 2

Cincinnati Reds 0

Crosley Field

Cincinnati, OH

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.