April 14, 1909: The dawn of a new era: St. Louis Browns fall in first game at Sportsman’s Park

The citizens of St. Louis had seen a lot of baseball played in the ballpark that stood at the intersection of Dodier Street and Grand Avenue. They had never seen it like this, though.

The citizens of St. Louis had seen a lot of baseball played in the ballpark that stood at the intersection of Dodier Street and Grand Avenue. They had never seen it like this, though.

After a single season in the upstart American League, the Milwaukee Brewers franchise was relocated to the “Gateway to the West” in the fall of 1901. The team borrowed a name from the past, the Brown Stockings, and moved into the city’s vacant Sportsman’s Park, the one along Dodier and Grand. The ballpark hadn’t housed a team in 10 years, not since the original Browns, of the National League, left Sportsman’s Park and moved to a ballpark several blocks northwest. For a time, they also called that one Sportsman’s Park, and the club ultimately changed its name to the Cardinals.

For a while, Grand Avenue’s Sportsman’s Park kept its character. In 1875, when August Solari opened his quaint 8,000-seat Grand Avenue Grounds for the original Brown Stockings, he situated home plate in the ballpark’s northeast corner, the one bounded by Dodier and Grand. As the new Browns took up residence for the 1902 season, however, home plate was moved to the ballpark’s northwest corner, bordered by Sullivan Avenue and Spring Street. There it remained for the next seven years, backed by a wooden grandstand.

Much advancement took place in ballpark architecture over those seven years. By the end of the 1908 season, as one mediocre Browns team after another toiled in their wooden home, new ballparks made of concrete and steel had been built in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. It was time, then, to modernize Sportsman’s Park, to furbish it, too, with concrete and steel, and to enlarge the grand old park to accommodate the unprecedented growth that baseball was enjoying. In 1909, Browns fans would cheer for their team in, if not a brand-new ballpark, in one that looked nothing like they had ever seen.

The first and perhaps most symbolic change in Sportsman’s alignment was a complete reversal of the field’s layout: home plate was moved from the northwest corner to the southwest, where it was now bordered by Dodier Street and Spring Avenue. Most impressively, a two-tiered concrete and steel grandstand that spanned from first base to third base was erected behind the new home-plate location, and the old wooden grandstand that had stood behind the old home plate was transformed into a spacious new left-field pavilion made of concrete. When construction was completed, Sportsman’s Park had been transformed into a gleaming new 25,000-seat jewel that represented the Browns’ future.

Naturally, the public was eager to get a look at the rebuilt Sportsman’s Park. Under the conditions, though, the crowd perhaps failed to live up to all that the event may have promised. When Opening Day arrived on April 14, 1909, it brought an unseasonably cold day, one in which “even the peanut boys sat about hugging themselves to keep warm.”1 Some intrepid fans arrived early and in great numbers to stake out choice viewing locations in the outfield. Indeed, reported the press the following day, “The crowd was out on the field behind the ropes a long time before the game started.”2 They weren’t necessarily in a placid mood, either. In a throng that stood rows deep, with many spectators perched on “benches, [or] boards set on anything that the crowd could lay its hands on to gain a point of vantage,” the enthusiastic patrons waged a “never-ending battle with the policemen on guard at the ropes.”3 Continuously, “the bluecoats shoved the crowd back,” as “those in the third, fourth and fifth rows crowded forward.”4 Battling mightily to keep things under control, “the officers would almost be carried off their feet.”5

What must have most astonished the crowd behind the ropes, of course, looking up from ground level, was the sheer size of the new ballpark, particularly the new two-level grandstand behind home plate. In describing the grandstand, a sportswriter noted, “One look at the comparatively small structure that was the grandstand last year and a comparison with the big stand was enough to convince everyone that they might as well try to hunt for the haystack needle as to find anybody in the new park.”6

If the crowd on the field, though, was undaunted by the cold, the chill higher up in the atmosphere seemed to have kept some folks away from the ballpark’s gaudy new grandstand. For while the first level was “crowded almost to its limit,” the second level, “with the exception of the boxes, which were almost all filled,” was not. That small crowd likely had to do with the chill wind that “swept through the stand with a whistle that went through almost any amount of wraps.”7

Out in left field, meantime, the site of the old wooden grandstands that for the previous seven years stood behind the old home plate, the new concrete pavilion was “filled, but not overcrowded.”8

All in all, wrote the press, “Whether it was the chilly wind or the fact that the park is so much larger than last year, the crowd could not seem to show the enthusiasm they displayed last year. … The cheering seemed light. There seemed to be a lack of concerted noisemaking.”9 Perhaps it was the play on the field, though, which had for so long been less than stellar, that generated such tempered applause.

With the exception of their first year in St. Louis, when they finished in second place, the Browns had never been very good. True, in 1908 they’d won 83 games and finished above .500 for the third time in their seven-year history; yet they’d finished only in fourth place, so contending for a championship remained elusive. Perhaps, though, this year they would build on that moderate success and finally make a run.

In 1909, however, that success was not to be. On this day, the Cleveland Naps, led by superstar player-manager Napoleon Lajoie, visited Sportsman’s Park for the season’s opening three-game series. After a thrilling American League pennant chase the previous year, during which Lajoie’s Naps played and lost one more game than the champion Detroit Tigers and finished an agonizing second, just a half-game behind, the Naps looked to repeat their high level of play. On the mound for Cleveland in St. Louis was the brilliant Addie Joss, winner of 92 games over the past four seasons. Opposing Joss was 34-year-old right-hander Jack Powell.

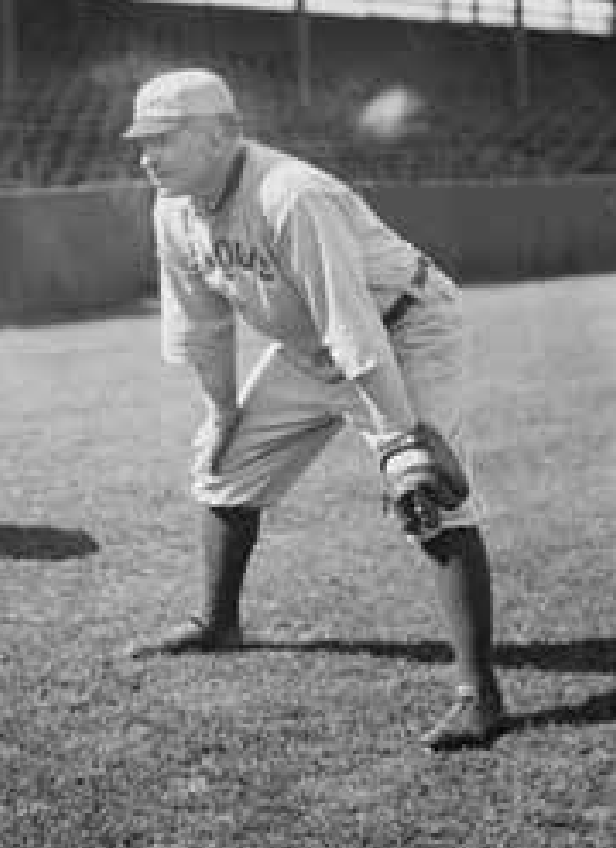

The flame-throwing Joss eventually became one of baseball’s immortals. John Joseph “Red” Powell is less acclaimed in baseball lore, but he was entering his 13th big-league season with 209 wins and was one of his era’s toughest pitchers. He would prove as much on this day. Displaying “perfect control” and “speed that increased as the game progressed,” Powell “allowed just five hits to the heavy-slugging Naps” and “outpitched” Joss, who had “neither the speed nor control to match Powell.”10 Still, Powell’s toughness wasn’t enough, for, as it was reported the next day, although the “Browns beat [the Naps] down for eight innings … in one frame, the fourth, Lajoie and his tribe won the game.”11

Key to the Naps’ win were two critical Browns errors and a lack of speed on the basepaths. During that Naps fourth inning, Browns shortstop Bobby Wallace and third baseman Hobe Ferris, both normally surehanded fielders, committed miscues. Those mistakes, together with three Naps hits, accounted for four runs in the frame. Although St. Louis touched Joss for eight hits, including three doubles, two Browns runners were cut down at second, one on a perfect throw from the outfield, and the other on a steal attempt. Were it not for those chances, plus the defensive blunders, the press opined, “Powell should have been the victor by a score of 2-1,” rather than the 4-2 loser.12

Despite the Browns loss, the next day it was reported that the team “played a game of ball that was a delight to the estimated 25,000 fans who swarmed [the] new park. … Not one of them left the place discouraged.”13 When the game was ended, the “rush for the streetcars was fierce. … [C]ars ran one after another” and “hundreds and hundreds had to wait for an available seat.”14

It was a scene that in one way or another would be repeated many times over the next 57 years as

St. Louis’s baseball fans headed home after yet another game at their beloved Ballpark at Dodier and Grand.

This article appears in “Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis: Home of the Browns and Cardinals at Grand and Dodier” (SABR, 2017), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. Click here to read more articles from this book online.

Photo Caption

Workhorse Jack Powell started the first game for the Browns in their new home, Sportsman’s Park. He won 245 games and lost 254 in his 16-year career (1897-1912). (Library of Congress)

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, and SABR.org.

Notes

1 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 15, 1909: 17.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 James Crusinberry, “Lack of Speed Still Injures Browns’ Play,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 15, 1909: 10.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 15, 1909: 17.

Additional Stats

Cleveland Naps 4

St. Louis Browns 2

Sportsman’s Park

St. Louis, MO

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.