April 16, 1972: Cubs rookie Burt Hooton fires no-hitter

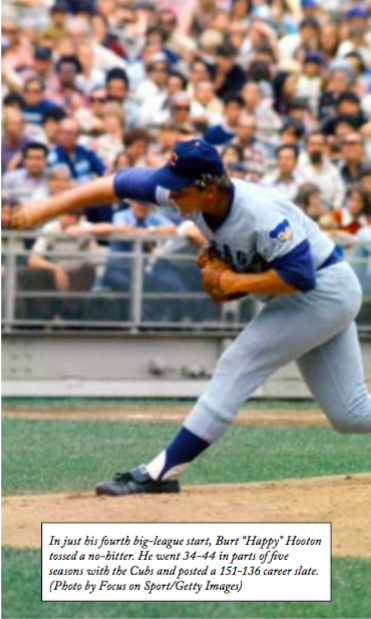

Few pitchers in Chicago Cubs history have burst on the scene with such an immediate explosive (albeit quickly fading) impact as Burt Hooton. Described by Windy City sportswriter Bob Logan as an “instant superstar” and compared with such icons of the sports-crazed city as Bobby Hull of the Black Hawks and Gayle Sayers of the Bears, Hooton kicked off the 1972 season by tossing a no-hitter in just his fourth big-league start.1 “You have to compare his knuckle-curve with a Sandy Koufax curve ball,” said Chicago Cubs catcher Randy Hundley ecstatically about the right-hander’s signature, seemingly unhittable pitch. “It starts at your head and winds up on the ground.”2

Few pitchers in Chicago Cubs history have burst on the scene with such an immediate explosive (albeit quickly fading) impact as Burt Hooton. Described by Windy City sportswriter Bob Logan as an “instant superstar” and compared with such icons of the sports-crazed city as Bobby Hull of the Black Hawks and Gayle Sayers of the Bears, Hooton kicked off the 1972 season by tossing a no-hitter in just his fourth big-league start.1 “You have to compare his knuckle-curve with a Sandy Koufax curve ball,” said Chicago Cubs catcher Randy Hundley ecstatically about the right-hander’s signature, seemingly unhittable pitch. “It starts at your head and winds up on the ground.”2

Longtime Cubs GM John Holland must have thought that he had won the jackpot. The Cubs drafted Hooton, an All-American at the University of Texas, in the secondary phase of the 1971 supplemental draft. Hooton was bombed in his debut, but proceeded to tear up the Triple-A Pacific Coast League, fanning 135 in 102 innings, including a league-record 19 in one game. A September call-up, Hooton punched out 15 in a three-hitter against the New York Mets, then shut them out on two hits six days later.

Hooton’s success rested on a knuckle curve, an innovative pitch he helped popularize. “I grab the ball with my first two fingers and let it slide off the tips, giving it a fastball motion by breaking my wrist,” he explained, noting that he developed the pitch when he couldn’t master a traditional flutter ball.3 The confounding pitch rotated in the opposite direction of his fastball and had an unexpected sharp downward break at the plate.4

Expectations for Hooton were high in 1972. “I saw Hooton for the first time this spring and I said that his live fastball was impressive,” mused Cubs pitching coach Larry Jansen, a former two-time 20-game winner with the New York Giants. “All you hear about is his knuckle-curve, but the fastball makes it effective.”5 Coming off a distant third-place finish in the NL East in ’71, 14 games behind the World Series champion Pittsburgh Pirates, the Cubs needed Hooton to join perennial 20-game winner Fergie Jenkins and dependable workhorses Milt Pappas and Bill Hands to have a shot at the divisional crown.

Mother Nature provided a rude welcome to Hooton as he took the mound against the Philadelphia Phillies on a Sunday afternoon in Chicago. The temperature hovered around 40 degrees and the wind swirled off Lake Michigan at 35 MPH, creating ideal conditions for a pitchers’ duel. The field was in poor shape from a rainy night and with storms in the forecast, there was discussion about postponing the game; however, players, and especially club owner Philip K. Wrigley, were itching to finally get the season started. A day earlier, the Phillies had beaten the Cubs, 4-2, on Opening Day, which had been delayed some 13 days by the first players strike in major-league history. While some players complained of not yet being in shape because of the strike-imposed layoff, that was not the case for Hooton, who had worked out with his former team at the University of Texas. According to the Tribune, Hooton tossed 128 pitches in the bullpen trying to warm up on the blustery day.6

Hooton breezed through the first four frames, but the weather played havoc with his knuckle curve. He walked three, but also profited from Don Kessinger’s perfectly timed leap to snare Denny Doyle’s “wicked liner” in the third.7 “I was fully extended,” said the All-Star shortstop, “but all you can do on that kind (of hit) is hope.”8

The Cubs took their whacks at right-hander Dick Selma, who had missed much of the previous season with an arm injury. In his eighth campaign with a 37-42 career slate, the converted reliever was making his first start since 1969. After twice stranding runners on first and third, the Cubs broke through in the fourth when Ron Santo led off with a sinking liner to left field. According to sportswriter Bill Conlin of the Philadelphia Daily News, the ball eluded Greg Luzinski’s “shoestring effort” and Santo reached second.9 After Rick Monday walked, Kessinger dropped a soft sacrifice bunt to the left side of the plate. Catcher Tim McCarver tossed the ball away for a two-base error, enabling Santo to cross the plate. Selma intentionally walked Hundley to fill the bases, then escaped the jam by retiring the next three batters.

The Cubs were still nursing a precarious 1-0 lead to start the seventh. After second baseman Glenn Beckert stabbed Deron Johnson’s bullet, Luzinski, who grew up in suburban Chicago, hit a monstrous shot to deep center field. “It probably would have bounced on Waveland Avenue,” quipped Bob Logan, “but the wind brought that ball back into the park.”10 Monday caught the ball on the warning track in front of the 368-foot sign. “I can’t hit a ball any harder than that,” claimed Luzinski, who had belted a home run off Jenkins the day before.11 It was the second time in three innings that Hooton was saved by the wind. In the fifth, Mike Anderson had hit a deep fly to left that “fluttered to a halt like a wounded bird,” wrote Conlin.12

Laboring after Luzinski’s blast, Hooton walked the next two batters, his sixth and seventh free passes of the game. Coach Pete Reiser, serving as manager for the second game in a row while skipper Leo Durocher recovered from a virus, came to the mound to calm his 22-year-old rookie. Hooton whiffed Doyle looking to end the frame.

The Cubs, who had stranded 10 runners through six innings, looked as though they might add three more to that total in the seventh. Billy Williams and Joe Pepitone led off with singles against Chris Short, in his second inning of relief. After Monday drew a one-out walk, Kessinger popped out. Hundley, who played in only nine games the previous season because of a serious knee injury, slapped a single to left to drive in two and give the North Siders a 3-0 cushion The Cubs tacked on another one in the eighth when Jose Cardenal led off with a triple and scored on Beckert’s single.

“I went to the knuckle-curve exclusively in the eighth and ninth innings,” said Hooton. “That’s when I felt the adrenaline starting to flow.13 For the first time since the third, Hooton retired the side in order in the eighth. As the sun momentarily broke through the clouds, he took the mound in the ninth just three outs away from becoming the seventh NL rookie to author a no-hitter.14 After dispatching Willie Montanez on a weak grounder, Hooton fell behind Deron Johnson, 3-and-0, quickly prompting Reiser to warm up relievers Phil Regan and Dan McGinn. He needn’t have bothered as Hooton roared back to strike out Johnson. On his 120th pitch of the game, Hooton fooled Luzinski on a sinking knuckle curve for his seventh strikeout to complete the no-hitter in 2 hours and 33 minutes.15

Hooton was mobbed by his teammates on the field and subsequently feted in the clubhouse. Phillip K. Wrigley announced that he was ripping up his prized hurler’s contract and giving him a $2,500 raise, and tossed in $500 to Hundley, who caught the first no-hitter in his career. According to the durable former All-Star who had led or co-led the majors in games caught four straight seasons (1966-1969), Hooton tossed about half knuckle curves and half fastballs, only one slider, and no changeups.16 Hooton faced 32 batters, punched out seven, and yielded only six outfield flies. No-hitters were not new to the affable youngster. He had thrown four in high school, two in college, and another one against Cuba as a member of the United States team in the 1970 Amateur World Series. Squandering many opportunities to pile on runs, the Cubs collected 12 hits (three each by Santo and Williams) and drew five walks, but hit only 2-for-13 with men in scoring position while leaving 13 runners stranded.

In his next start, Hooton held the New York Mets to two runs on six hits in seven innings while fanning nine, but came up short against Tom Seaver, who tossed a four-hit shutout to win, 4-0. Big-league hitters eventually adjusted to Hooton’s knuckle curve, which many sportswriters described as a gimmick or trick pitch. He finished a productive rookie campaign with an 11-14 record and robust 2.80 ERA in 218⅓ innings. He went on to win 151 games (and lose 136), including 29 shutouts, in a 15-year career, spent primarily with the Cubs and Los Angeles Dodgers, but never seriously flirted with a no-hitter again.

This article appears in “Wrigley Field: The Friendly Confines at Clark and Addison” (SABR, 2019), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To read more stories from this book online, click here.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Newspapers.com, and the SABR BioProject.

https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHN/CHN197204160.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1972/B04160CHN1972.htm

Notes

1 Bob Logan, “Hooton No-Hits Phils, 4-0,” Chicago Tribune, April 17, 1972: C1.

2 Ibid.

3 “Found! A No-Hit Pitcher Who Says, ‘I Was a Fluke’,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 17, 1972: 21.

4 Bruce Keidan, “Phillies Can’t Hit Knuckle-Curve Ball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 17, 1972: 10.

5 Logan.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Bill Conlin, “Phils Aren’t HOOton,” Philadelphia Daily News, April 17, 1972: 68.

10 Logan.

11 Keidan.

12 Bill Conlin, “A Walter Mitty Fantasy Comes True,” Philadelphia Daily News, April 17, 1972: 63.

13 Keidan.

14 Hooton joined Christy Mathewson (1901), Nick Maddox (1907), Jeff Tesreau (1912), Paul Dean (1934), Sam Jones (1955), and Don Wilson (1967).

15 See a short clip of Hooton’s no-hitter on YouTube. It includes Kessinger’s spectacular catch in the third, Monday’s catch of Luzinski’s deep fly in the seventh, and Hooton striking out Luzinski to end the game. https://youtube.com/watch?v=iDXveU8P-TA

16 Logan.

Additional Stats

Chicago Cubs 4

Philadelphia Phillies 0

Wrigley Field

Chicago, IL

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.