April 19, 1890: Debut of the Players League

The Players League opened the 1890 season with seven of eight clubs playing in the same city as National League clubs; Buffalo was the lone exception. Under the sponsorship and direction of the players’ Brotherhood, the Players League also commenced play on the same day as the National League, with four games on Saturday, April 19, 1890. The American Association had commenced its campaign two days earlier. New York, Boston, Pittsburgh, and Buffalo hosted games, with all but Buffalo in direct competition with a National League game.

Organized the previous offseason by players disenchanted by labor relations in the existing Organized Baseball structure, the Players League offered teams in which the players themselves retained partial ownership. The concept attracted most of the game’s stars, and the popularity of those stars cut deeply into the existing leagues. Of the 72 players appearing in Players League box scores on April 19, all but two had played in either the National League or American Association in 1889. That star power showed itself at the turnstiles of the four Opening Day sites.

Philadelphia at New York. More than 12,000 arrived at the Brotherhood Park on a cold afternoon for the inaugural Players League match in New York. The crowd greeted the Players League Giants with “such cheering and yelling, throwing up of hats and general enthusiasm as, perhaps, had never before been witnessed at a ball game.”[fn]Sporting Life, April 26, 1890, p. 3.[/fn] New York featured a lineup remarkably similar to the regular lineup for the 1889 National League Giants; the entire lineup had played for the ’89 National League outfit and seven had been regulars. Tim Keefe, who won 28 games for the National League Giants the previous year and whose sporting goods company supplied the Players League game ball, pitched for New York. Charlie Buffinton, who equaled Keefe’s 28 wins with the ’89 Phillies, took the mound for the Players League Quakers.

Philadelphia at New York. More than 12,000 arrived at the Brotherhood Park on a cold afternoon for the inaugural Players League match in New York. The crowd greeted the Players League Giants with “such cheering and yelling, throwing up of hats and general enthusiasm as, perhaps, had never before been witnessed at a ball game.”[fn]Sporting Life, April 26, 1890, p. 3.[/fn] New York featured a lineup remarkably similar to the regular lineup for the 1889 National League Giants; the entire lineup had played for the ’89 National League outfit and seven had been regulars. Tim Keefe, who won 28 games for the National League Giants the previous year and whose sporting goods company supplied the Players League game ball, pitched for New York. Charlie Buffinton, who equaled Keefe’s 28 wins with the ’89 Phillies, took the mound for the Players League Quakers.

New York opened the scoring with three runs in the top of the second inning, but Philadelphia answered with seven in the bottom half. The Giants chipped away at Philadelphia’s lead with one run in the fourth and two more in the sixth.

After Philadelphia added one run in the bottom of the sixth to take an 8–6 lead, New York regained the lead with a five-run eighth inning and held that 11–8 lead into the ninth. Philadelphia batted last despite playing away from home. A combination of two hit batsmen, two singles, and a double provided the spark for Philadelphia’s come-from-behind 12–11 win. As a reward for their season-opening win, the Philadelphia players were promised new suits.[fn]Op cit, p. 1-2.[/fn]

Chicago at Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh hosted Chicago before approximately 8,500 at Exposition Park. The crowd “gave the players a good reception and made them jubilant.”[fn]Op cit, p. 3.[/fn] Charlie Comiskey, longtime member of the American Association St. Louis Browns, led Chicago into the Players League campaign. His nine comprised of former Browns teammates as well as members of the ’89 National League Chicago White Stockings.

Comiskey contributed to his club’s cause with one hit in four at-bats and two runs. Those contributions helped Chicago score seven runs in the first three frames. Pittsburgh pitcher Pud Galvin was undone by his defense as well as Chicago’s bats. Chicago tagged Galvin for 10 runs and 12 hits over the nine innings, and Pittsburgh’s seven errors hurt the home team’s cause. Chicago pitcher Silver King scattered six hits and surrendered two unearned runs in a 10–2 Chicago victory.

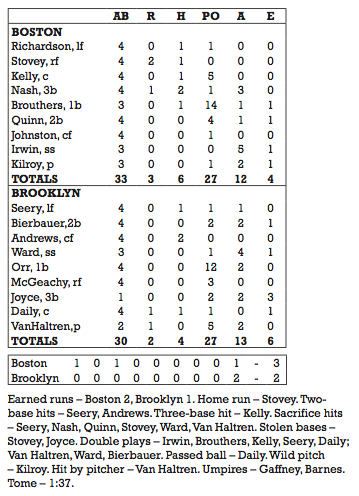

Brooklyn at Boston. After an exhibition schedule in which it won all 12 matches,[fn]Ibid.[/fn] Boston hosted Brooklyn at the Congress Street Grounds. Boston’s 3–2 win in front of more than 8,000 fans included elements of a modern-day pitchers’ duel. Boston’s Matt Kilroy and Brooklyn’s George Van Haltren allowed only 10 hits between them. Boston third baseman Billy Nash and Brooklyn center fielder Ed Andrews were the only batsmen with multi-hit games.

Boston opened the scoring with right fielder Harry Stovey’s first-inning home run, one of two four-baggers in the four Opening Day games. Boston doubled its lead in the third inning when an error by Brooklyn shortstop John Montgomery Ward allowed Stovey to get on base. He stole second, then scored on a double by catcher and captain Mike “King” Kelly. In the top of the ninth inning, Boston added what proved to be the difference in the game when Nash scored.

After failing to score in the first eight innings, Brooklyn rallied in the bottom of the ninth. Left fielder Emmett Seery’s two-out, two-run double allowed Brooklyn to pull within a run. The game ended when the next batter, second baseman Lou Bierbauer, grounded out.

Cleveland at Buffalo. Buffalo hosted Cleveland before 3,125 at Olympic Park, and romped to a 23–2 win over the visiting Infants. The Bisons scored in each of the first six innings and every batter but one crossed home plate at least twice. Pitcher George Haddock scored more runs (four) than he surrendered (two).

The Bisons offense proved effective in garnering 17 hits, with second basemen Sam Wise contributing four and right fielder John Rainey hitting a home run. Cleveland assisted in its own demise with seven errors and pitcher Henry Gruber’s 16 walks.

Over the course of the first four games of season, Buffalo would score 79 runs in completing a fourgame season-opening sweep of Cleveland. The promise of this fast start was undone with 11 losses in the next 12 games en route to a 36–96 season that left the Bisons 20 games behind seventh-place Cleveland.

After the first day of games, Brotherhood leader Ward pronounced himself satisfied with the start to the season. He asserted that the Brotherhood movement was “in accord with the spirit of the times” and “the Brotherhood grounds … [were] far better than those of the League.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn] Ward had reason to feel satisfied. In the three cities where the Players League and National League went headto- head, the Players League teams won the attendance battle by approximately 3 to 1.

That pattern continued through the remainder of the season. But with the baseball market glutted by an extra league, all teams in all three leagues lost money. At season’s end, the established leagues, relying on their deeper financial reserves, managed to coerce backers of the Players League into going out of business.[fn]Other references used in preparation of this article included: Koszarek, Ed. The Players League ( Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2006). Nemec, Nemec. The Great Encyclopedia of Nineteenth Century Major League Baseball (2d ed.) (Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 2006). Baseball-reference.com, Retrosheet.org[/fn]

This essay was originally published in “Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century” (2013), edited by Bill Felber. Download the SABR e-book by clicking here.

Additional Stats

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.